Comparative Study of Public Housing Policies of Hong Kong and Singapore Richard Junqi Zhang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong Final Report

Urban Displacement Project Hong Kong Final Report Meg Heisler, Colleen Monahan, Luke Zhang, and Yuquan Zhou Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Research Questions 5 Outline 5 Key Findings 6 Final Thoughts 7 Introduction 8 Research Questions 8 Outline 8 Background 10 Figure 1: Map of Hong Kong 10 Figure 2: Birthplaces of Hong Kong residents, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 11 Land Governance and Taxation 11 Economic Conditions and Entrenched Inequality 12 Figure 3: Median monthly domestic household income at LSBG level, 2016 13 Figure 4: Median rent to income ratio at LSBG level, 2016 13 Planning Agencies 14 Housing Policy, Types, and Conditions 15 Figure 5: Occupied quarters by type, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Figure 6: Domestic households by housing tenure, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Public Housing 17 Figure 7: Change in public rental housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 18 Private Housing 18 Figure 8: Change in private housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 19 Informal Housing 19 Figure 9: Rooftop housing, subdivided housing and cage housing in Hong Kong 20 The Gentrification Debate 20 Methodology 22 Urban Displacement Project: Hong Kong | 1 Quantitative Analysis 22 Data Sources 22 Table 1: List of Data Sources 22 Typologies 23 Table 2: Typologies, 2001-2016 24 Sensitivity Analysis 24 Figures 10 and 11: 75% and 25% Criteria Thresholds vs. 70% and 30% Thresholds 25 Interviews 25 Quantitative Findings 26 Figure 12: Population change at TPU level, 2001-2016 26 Figure 13: Change in low-income households at TPU Level, 2001-2016 27 Typologies 27 Figure 14: Map of Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Table 3: Table of Draft Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Typology Limitations 29 Interview Findings 30 The Gentrification Debate 30 Land Scarcity 31 Figures 15 and 16: Google Earth Images of Wan Chai, Dec. -

Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong By

Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong by Cecilia Louise Chu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor C. Greig Crysler Professor Eugene F. Irschick Spring 2012 Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Copyright 2012 by Cecilia Louise Chu 1 Abstract Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Cecilia Louise Chu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair This dissertation traces the genealogy of property development and emergence of an urban milieu in Hong Kong between the 1870s and mid 1930s. This is a period that saw the transition of colonial rule from one that relied heavily on coercion to one that was increasingly “civil,” in the sense that a growing number of native Chinese came to willingly abide by, if not whole-heartedly accept, the rules and regulations of the colonial state whilst becoming more assertive in exercising their rights under the rule of law. Long hailed for its laissez-faire credentials and market freedom, Hong Kong offers a unique context to study what I call “speculative urbanism,” wherein the colonial government’s heavy reliance on generating revenue from private property supported a lucrative housing market that enriched a large number of native property owners. Although resenting the discrimination they encountered in the colonial territory, they were able to accumulate economic and social capital by working within and around the colonial regulatory system. -

Right to Adequate Housing There Were No Recommendations Made on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (HKSAR) in the Second UPR Cycle

Right to Adequate Housing There were no recommendations made on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (HKSAR) in the Second UPR Cycle. Framework in HKSAR HKSAR is the most expensive city, worldwide, in which to buy a home. Broadly, housing is categorized into; permanent private housing, public rental housing, and public housing. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) has been extended to HKSAR and its implementation is covered under Article 39 of the Basic Law. The middle income group is squeezed by the rocketing prices, relative to low incomes; particularly given that there is no control to prevent public rental rates being set against the wider commercial property market. The crisis in the affordability of housing in Hong Kong has been noted by successive Chief Executives since 2013. For example, the current Chief Executive, Carrie Lam, said in her Policy Address in October 2017 that “meeting the public’s housing needs is our top priority”. However, despite these statements, since 2013 there has been a continued surge in property prices, rental prices and an increase in the number of homeless. Concerns with the lack of affordable and adequate housing were raised by the ICESCR Committee in their 2014 Concluding Observations on HKSAR. Challenges Cases, facts and comments • The government has not taken • Median property prices are 19.4 times the median sufficient action to protect and salary. promote the right to adequate housing • In the years 2007-2016, property prices in HKSAR under Article 11(1) of ICESCR, including increased by 176.4%, compared to a 42.9% rise in the right to choose one’s residence the median monthly income. -

Public Housing in the Global Cities: Hong Kong and Singapore at the Crossroads

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 11 January 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202101.0201.v1 Public Housing in the Global Cities: Hong Kong and Singapore at the Crossroads Anutosh Das a, b a Post-Graduate Scholar, Department of Urban Planning and Design, The University of Hong Kong (HKU), Hong Kong; E-mail: [email protected] b Faculty Member, Department of Urban & Regional Planning, Rajshahi University of Engineering & Technology (RUET), Bangladesh; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Affordable Housing, the basic human necessity has now become a critical problem in global cities with direct impacts on people's well-being. While a well-functioning housing market may augment the economic efficiency and productivity of a city, it may trigger housing affordability issues leading crucial economic and political crises side by side if not handled properly. In global cities e.g. Singapore and Hong Kong where affordable housing for all has become one of the greatest concerns of the Government, this issue can be tackled capably by the provision of public housing. In Singapore, nearly 90% of the total population lives in public housing including public rental and subsidized ownership, whereas the figure tally only about 45% in Hong Kong. Hence this study is an effort to scrutinizing the key drivers of success in affordable public housing through following a qualitative case study based research methodological approach to present successful experience and insight from different socio-economic and geo- political context. As a major intervention, this research has clinched that, housing affordability should be backed up by demand-side policies aiming to help occupants and proprietors to grow financial capacity e.g. -

List of Abbreviations

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AAHK Airport Authority Hong Kong AAIA Air Accident Investigation Authority AFCD Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department AMS Auxiliary Medical Service ASC Aviation Security Committee ASD Architectural Services Department BD Buildings Department CAD Civil Aviation Department CAS Civil Aid Service CCCs Command and Control Centres CEDD Civil Engineering and Development Department CEO Chief Executive’s Office / Civil Engineering Office CESC Chief Executive Security Committee CEU Casualty Enquiry Unit CIC Combined Information Centre CS Chief Secretary for Administration DECC District Emergency Co-ordination Centre DEVB Development Bureau DH Department of Health DO District Officer DSD Drainage Services Department EDB Education Bureau EMSC Emergency Monitoring and Support Centre EMSD Electrical and Mechanical Services Department EPD Environmental Protection Department EROOHK Emergency Response Operations Outside the HKSAR ESU Emergency Support Unit ETCC Emergency Transport Coordination Centre FCC Food Control Committee FCP Forward Control Point FEHD Food and Environmental Hygiene Department FSCC Fire Services Communication Centre FSD Fire Services Department GEO Geotechnical Engineering Office GFS Government Flying Service GL Government Laboratory GLD Government Logistics Department HA Hospital Authority HAD Home Affairs Department HD Housing Department HyD Highways Department HKO Hong Kong Observatory HKPF Hong Kong Police Force HKSAR Hong Kong Special Administrative Region HQCCC Police Headquarters Command -

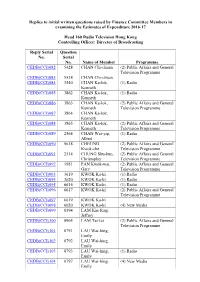

Replies to Initial Written Questions Raised by Finance Committee Members in Examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2016-17 Head

Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2016-17 Head 160 Radio Television Hong Kong Controlling Officer: Director of Broadcasting Reply Serial Question No. Serial No. Name of Member Programme CEDB(CCI)082 5428 CHAN Chi-chuen (2) Public Affairs and General Television Programme CEDB(CCI)083 5518 CHAN Chi-chuen CEDB(CCI)084 3540 CHAN Ka-lok, (1) Radio Kenneth CEDB(CCI)085 3862 CHAN Ka-lok, (1) Radio Kenneth CEDB(CCI)086 3863 CHAN Ka-lok, (2) Public Affairs and General Kenneth Television Programme CEDB(CCI)087 3864 CHAN Ka-lok, Kenneth CEDB(CCI)088 3865 CHAN Ka-lok, (2) Public Affairs and General Kenneth Television Programme CEDB(CCI)089 2564 CHAN Wai-yip, (1) Radio Albert CEDB(CCI)090 5618 CHEUNG (2) Public Affairs and General Kwok-che Television Programme CEDB(CCI)091 2514 CHUNG Shu-kun, (2) Public Affairs and General Christopher Television Programme CEDB(CCI)092 1981 FAN Kwok-wai, (2) Public Affairs and General Gary Television Programme CEDB(CCI)093 3619 KWOK Ka-ki (1) Radio CEDB(CCI)094 3620 KWOK Ka-ki (1) Radio CEDB(CCI)095 6616 KWOK Ka-ki (1) Radio CEDB(CCI)096 6617 KWOK Ka-ki (2) Public Affairs and General Television Programme CEDB(CCI)097 6619 KWOK Ka-ki CEDB(CCI)098 6620 KWOK Ka-ki (4) New Media CEDB(CCI)099 0394 LAM Kin-fung, Jeffrey CEDB(CCI)100 0964 LAM Tai-fai (2) Public Affairs and General Television Programme CEDB(CCI)101 0791 LAU Wai-hing, Emily CEDB(CCI)102 0792 LAU Wai-hing, Emily CEDB(CCI)103 0793 LAU Wai-hing, (1) Radio Emily CEDB(CCI)104 0797 LAU Wai-hing, (4) New Media Emily Reply Serial Question No. -

The Ombudsman, Hong Kong, Annual Report 2019/20

The Ombudsman, Hong Kong Annual Report 2019/20 Annual Report of The Ombudsman, Hong Kong 2019/20 Hong Kong The Ombudsman, Annual Report of • 32nd Issue POSITIVE COMPLAINT CULTURE FOR BETTER ADMINISTRATION Key Figures of the Year Complaints Complaints received 19,767 completed 19,838 93% 5% by email/fax by post 17,031 2,418 Closed after Concluded by assessment inquiry 2% 1% in person by phone 240 149 Concluded by full Resolved by investigation mediation 99.4% 93.5% 99.3% (target: 99.0%) (target: 80.0%) (target: 99.0%) Complaints closed within Complaints concluded Complaints concluded 15 working days after within 3 months within 6 months initial assessment due to jurisdictional restrictions Cases related 10 to access to Direct Investigations information completed completed 84 Recommendations given 177 Enquiries received 8,581 VISION To ensure that Hong Kong is served by a fair and efficient public administration which is committed to accountability, openness and quality of service MISSION Through independent, objective and impartial investigation, to redress grievances and address issues arising from maladministration in the public sector and bring about improvement in the quality and standard of and promote fairness in public administration VALUES • Maintaining impartiality and objectivity in our investigations • Making ourselves accessible and accountable to the public and organisations under our jurisdiction • According the public and organisations courtesy and respect • Upholding professionalism in the performance of our functions CONTENTS -

Privatising Management Services in Subsidised Housing in Hong Kong

The research register for this journal is available at The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at http://www.mcbup.com/research_registers http://www.emerald-library.com/ft Privatising Privatising management management services in subsidised housing services in Hong Kong Ling Hin Li and Amy Siu 37 Department of Real Estate and Construction, The University of Received August 1998 Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China Revised June 2000 Keywords Tenant, Property management, Housing, Privatization, Hong Kong Abstract Privatisation of services from the public sector is topical currently mainly because of the potential savings and efficiency to be gained. In the aspect of property management, the Hong Kong Housing Authority owns more than 600,000 units of public housing flats and the requirement for good and efficient property management services is enormous. The current policy of privatising these services to the private management agents has proved to be a correct direction in terms of retaining the growth of the public sector, and also improving the level of services to the tenants. While the privatisation scheme might bring in more opportunities for growth of the property management companies in the private sector, it is more important for the government to forge a proper transitional arrangement to switch to full private management in order not to endanger the already low morale in the public sector. 1. Introduction Privatisation is a general term describing a multitude of government initiatives designed to increase the role of the private sector in the provision of the conventional public services. The principles behind privatisation represent an ideology that puts larger emphasis on the efficiency of the market forces than on the public sector. -

Affordable Social Housing: Modular Flat Design for Mass Customization in Public Rental Housing in Hong Kong

AFFORDABLE SOCIAL HOUSING: MODULAR FLAT DESIGN FOR MASS CUSTOMIZATION IN PUBLIC RENTAL HOUSING IN HONG KONG Irene Cheng Assistant Director Development and Construction Division, Hong Kong Housing Authority, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. Irene.cheng@housinga uthority.gov.hk Connie K. Y. YEUNG, Chief Architect, Development and Construction Division, Hong Kong Housing Authority, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, [email protected] Clarence K.Y. FUNG, Senior Architect, Development and Construction Division, Hong Kong Housing Authority, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. [email protected] Wilfred K.W. LAI, Architect, Development and Construction Division, Hong Kong Housing Authority, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. [email protected] Summary Since 2008, the Hong Kong Housing Authority has been developing a new design strategy: adopting modular flat design for mass customization in public rental housing in Hong Kong. The Modular Flat Design (2008 Version) has been optimized to strike a better balance amongst various factors including valuable land resources, buildability and cost effectiveness and user-friendliness including responses to the findings from Residents Survey. This is a product of cumulative experiences over years. By applying modular flats to the building design in affordable social housing developments, Hong Kong Housing Authority can assure quality and sustainability while at the same time achieving consistency in standards.. Keywords : Public Rental Housing, Modular Flat Design, Standardization & Modularization, Universal Design, Sustainability 1. Public Housing Design Development The Hong Kong Housing Authority is a statutory body established in April 1973 under the Housing Ordinance. The Hong Kong Housing Authority plans, builds, manages and maintains public housing in Hong Kong. -

Jun 2 0 1997 N

Hong Kong: City of Edges South East Kowloon Development by Wai-Kuen Chan B.S. Arch, City College of New York, 1992 B. Arch, City College of New York, 1993 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, JUNE 1997 c 1997 Wai-Kuen Chan. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Wai-Kuen Chan Department of Architecture May 9, 1997 Certified by: Julian Beinart Professor of Architecture and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Roy Strickland Associate Professor of Architecture Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students JUN 2 0 1997 N -C CO Readers Reader: John DeMONCHAUX Title: Professor of Architecture and Planning Reader: Michael Dennis Title: Professor of Architecture lil O O) Hon g Kon g: City of Edges South East Kowloon Development by Wai-Kuen Chan Abstract Submitted To The Department Of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Master Of Science In Architecture Studies At The Massachusetts Institute Of Technology, June 1997 Many extraordinary cities are developed along the edges of water into different directions. Yet, the city of Hong Kong has been formed along narrow strips of scarce flat-land around the harbor and from reclamations of land-fills. Urban fabrics are stretched along water edges of the Victoria Harbor with distinct characters. For the rapidly developing cities, these urban fragments are elemental and essential to sustain. -

Civil Service Vacancy HOUSING DEPARTMENT Architect Salary

Civil Service Vacancy HOUSING DEPARTMENT Architect Salary : Master Pay Scale Point 32 ($70,465 per month) to Master Pay Scale Point 44 ($110,170 per month) Entry Requirements : Candidates should (a) be Members of the Hong Kong Institute of Architects (HKIA), or equivalent, and be Registered Architects of the Hong Kong Architects Registration Board; (b) have a pass result in the Aptitude Test in the Common Recruitment Examination (CRE); and (c) have met the language proficiency requirements of Level 1 results in the two language papers (Use of Chinese and Use of English) in the CRE, or equivalent. [See Note (2)]. Notes: (1) All qualifications and working experience required should be obtained on or before the closing date for application. (2) The results of the Use of Chinese (UC) and Use of English (UE) papers in the CRE are classified as Level 2, Level 1 or Fail, with Level 2 being the highest. For civil service appointment purpose, Level 5 or above in Chinese Language of the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination (HKDSEE); or Grade C or above in Chinese Language and Culture or Chinese Language and Literature of the Hong Kong Advanced Level Examination (HKALE), are accepted as equivalent to Level 2 in the UC paper of the CRE. Level 4 in Chinese Language of the HKDSEE; or Grade D in Chinese Language and Culture or Chinese Language and Literature of the HKALE, are accepted as equivalent to Level 1 in the UC paper of the CRE. Level 5 or above in English Language of the HKDSEE; or Grade C or above in Use of English of the HKALE; or Grade C or above in English Language of the General Certificate of Education (Advanced Level) (GCE A Level), are accepted as equivalent to Level 2 in the UE paper of the CRE. -

Housing Officer

Civil Service Vacancy Housing Department Housing Officer Salary: Master Pay Scale Point 9 ($22,725) to Master Pay Scale Point 27 ($55,995) per month Entry Requirements: Candidates should have – (a)(i) Level 3 or equivalent (Note 1) or above in five subjects in the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination (HKDSEE) (Note 2), or equivalent; or (ii) Grade E or above in two subjects at Advanced Level in the Hong Kong Advanced Level Examination and Level 3 (Note 3) / Grade C or above in three other subjects in the Hong Kong Certificate of Education Examination (HKCEE) (Note 2), or equivalent; and (b) met the language proficiency requirements of Level 3 (Note 3) or above in Chinese Language and English Language in HKDSEE or HKCEE, or equivalent and be able to speak fluent Cantonese and English. (Relevant working experience would be an advantage.) Notes: (1) For civil service appointment purpose, “Attained with Distinction” in Applied Learning subjects (subject to a maximum of two Applied Learning subjects), and Grade C in Other Language subjects in the HKDSEE are accepted as equivalent to Level 3 in the New Senior Secondary subjects in the HKDSEE. “Attained” in Applied Learning subjects (subject to a maximum of two Applied Learning subjects), and Grade E in Other Language subjects in the HKDSEE are accepted as equivalent to Level 2 in the New Senior Secondary subjects in the HKDSEE. (2) The subjects may include Chinese Language and English Language. (3) For civil service appointment purpose, ‘Grade C’ and ‘Grade E’ in Chinese Language and English Language (Syllabus B) in the HKCEE before 2007 are accepted administratively as comparable to ‘Level 3’ and ‘Level 2’ respectively in Chinese Language and English Language in the 2007 HKCEE and henceforth.