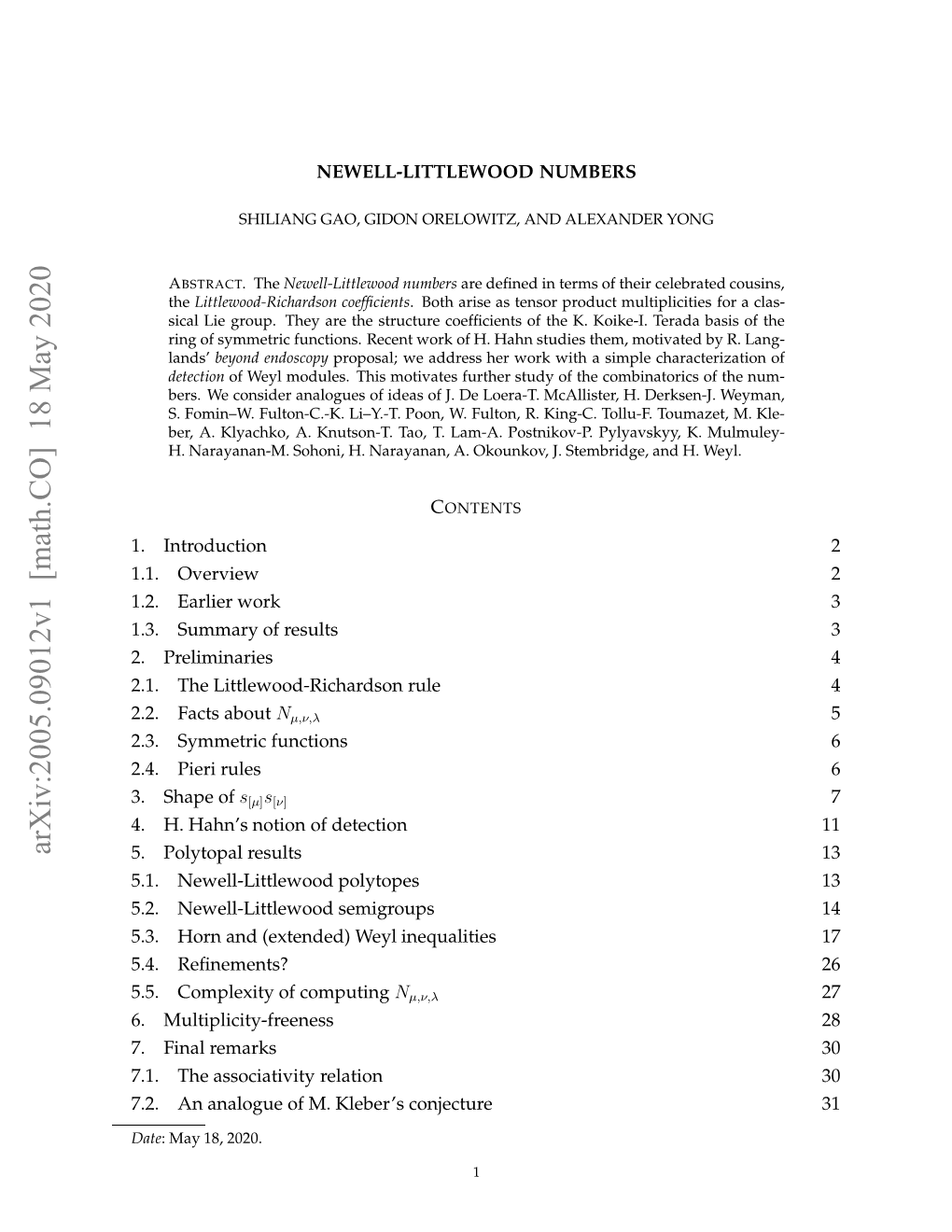

Arxiv:2005.09012V1 [Math.CO] 18 May 2020 Date ..Fcsabout Facts 2.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Missing Boundaries of the Santaló Diagrams for the Cases (D

Discrete Comput Geom 23:381–388 (2000) Discrete & Computational DOI: 10.1007/s004540010006 Geometry © 2000 Springer-Verlag New York Inc. The Missing Boundaries of the Santal´o Diagrams for the Cases (d,ω,R) and (ω, R, r) M. A. Hern´andez Cifre and S. Segura Gomis Departamento de Matem´aticas, Universidad de Murcia, 30100 Murcia, Spain {mhcifre,salsegom}@fcu.um.es Abstract. In this paper we solve two open problems posed by Santal´o: to obtain complete systems of inequalities for some triples of measures of a planar convex set. 1. Introduction There is abundant literature on geometric inequalities for planar figures. These inequali- ties connect several geometric quantities and in many cases determine the extremal sets which satisfy the equality conditions. Each new inequality obtained is interesting on its own, but it is also possible to ask if a collection of inequalities concerning several geometric magnitudes is large enough to determine the existence of the figure. Such a collection is called a complete system of inequalities: a system of inequalities relating all the geometric characteristics such that, for any set of numbers satisfying those conditions, a planar figure with these values of the characteristics exists in the given class. Santal´o [7] considered the area, the perimeter, the diameter, the minimal width, the circumradius, and the inradius of a planar convex K (A, p, d, ω, R and r, respectively). He tried to find complete systems of inequalities concerning either two or three of these measures. He found that, for pairs of measures, the known classic inequalities between them already form a complete system. -

THE A·B·C·Ds of SCHUBERT CALCULUS

THE A·B·C·Ds OF SCHUBERT CALCULUS COLLEEN ROBICHAUX, HARSHIT YADAV, AND ALEXANDER YONG ABSTRACT. We collect Atiyah-Bott Combinatorial Dreams (A·B·C·Ds) in Schubert calculus. One result relates equivariant structure coefficients for two isotropic flag manifolds, with consequences to the thesis of C. Monical. We contextualize using work of N. Bergeron- F. Sottile, S. Billey-M. Haiman, P. Pragacz, and T. Ikeda-L. Mihalcea-I. Naruse. The relation complements a theorem of A. Kresch-H. Tamvakis in quantum cohomology. Results of A. Buch-V. Ravikumar rule out a similar correspondence in K-theory. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Conceptual framework. Each generalized flag variety G=B has finitely many orbits under the left action of the (opposite) Borel subgroup B− of a complex reductive Lie group ∼ G. They are indexed by elements w of the Weyl group W = N(T)=T, where T = B \ B− is a maximal torus. The Schubert varieties are closures Xw of these orbits. The Poincare´ duals ? of the Schubert varieties fσwgw2W form a Z-linear basis of the cohomology ring H (G=B). The Schubert structure coefficients are nonnegative integers, defined by X w σu ` σv = cu;vσw: w2W w Geometrically, cu;v 2 Z≥0 counts intersection points of generic translates of three Schubert varieties. The main problem of modern Schubert calculus is to combinatorially explain this positivity. For Grassmannians, this is achieved by the Littlewood-Richardson rule [13]. The title alludes to a principle, traceable to M. Atiyah-R. Bott [6], that equivariant coho- mology is a lever on ordinary cohomology. -

Lectures on the Mathematics of Quantum Mechanics Volume II: Selected Topics

Gianfausto Dell'Antonio Lectures on the Mathematics of Quantum Mechanics Volume II: Selected Topics February 17, 2016 Mathematical Department, Universita' Sapienza (Rome) Mathematics Area, ISAS (Trieste) 2 A Caterina, Fiammetta, Simonetta Il ne faut pas toujours tellement epuiser un sujet q'on ne laisse rien a fair au lecteur. Il ne s'agit pas de fair lire, mais de faire penser Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu Contents 1 Lecture 1. Wigner functions. Coherent states. Gabor transform. Semiclassical correlation functions ........................ 11 1.1 Coherent states . 15 1.2 Husimi distribution . 17 1.3 Semiclassical limit using Wigner functions . 21 1.4 Gabor transform . 24 1.5 Semiclassical limit of joint distribution function . 25 1.6 Semiclassical limit using coherent states . 26 1.7 Convergence of quantum solutions to classical solutions . 29 1.8 References for Lecture 1 . 34 2 Lecture 2 Pseudifferential operators . Berezin, Kohn-Nirenberg, Born-Jordan quantizations ................................. 35 2.1 Weyl symbols . 36 2.2 Pseudodifferential operators . 36 2.3 Calderon - Vaillantcourt theorem . 39 2.4 Classes of Pseudodifferential operators. Regularity properties. 44 2.5 Product of Operator versus products of symbols . 46 2.6 Correspondence between commutators and Poisson brackets; time evolution . 49 2.7 Berezin quantization . 51 2.8 Toeplitz operators . 53 2.9 Kohn-Nirenberg Quantization . 54 2.10 Shubin Quantization . 55 2.11 Born-Jordarn quantization . 56 2.12 References for Lecture 2 . 57 4 Contents 3 Lecture 3 Compact and Schatten class operators. Compactness criteria. Bouquet of Inequalities ........................... 59 3.1 Schatten Classes . 64 3.2 General traces . 65 3.3 General Lp spaces . -

Mathematical Physics, Analysis and Geometry

ISSN 0002-9920 of the American Mathematical Society February 2001 Volume 48, Number 2 Mathematics for Teaching page 168 0 2 0 1 1 Honeycombs and 2 Sums of Hermitian 2 0 Matrices page 175 -3,-3 0 Lawrence Meeting -2,-2,-2 page 276 Las Vegas Meeting page 278 2 2 Hoboken Meeting page 280 -3 -2 -1 -4 -1,-1 2 0 2 0 -4 -2 0 -3 -2 -1 Honeycombs and Tensor Products (see page 186) The ' frl~ te igra·H~n ofrMatfT Type~ett ·rng and-CoFripufer Algebra 'I '\':. l_t •\ \ ,J_! \. Sci e The Gold Standard for Mathematical Publishing and the Easiest-to-Use Computer Algebra System Scientific WorkPlace makes writing and doing mathematics easier than you ever imagined possible. Because Scientific WorkPlace thinks like you do, you can compose and edit your documents directly on the screen, without being forced to think in a programming language. A simple click of a button allows you to typeset your document in lbTE)C . This lets you concentrate on creating a correct paper, while Scientific WorkPlace ensures that it is a beautiful one. With Scientific WorkPlace, you can also compute and plot solutions with the integrated computer algebra system. Increase Your Productivity Scientific WorkPlace enables both professional and support staff to produce stunning results quickly and easily, without having to know TEX™, lbTEX, or computer algebra syntax. And, as an added benefit, MacKichan Software provides free, prompt, and knowledgeable technical support. Visit our homepage for free evaluation copies of all our software. cKichan SOFTWARE, INC . Email: info@mackichan .com • Toll Free: 877-724-9673 • Fax: 206-780-2857 MacKichan Software, Inc. -

Sparse Bounds in Harmonic Analysis and Semiperiodic Estimates

Sparse Bounds in Harmonic Analysis and Semiperiodic Estimates by Alexander Barron May 2019 2 c Copyright 2019 by Alexander Barron i This dissertation by Alex Barron is accepted in its present form by the Department of Mathematics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date Jill Pipher, Ph.D., Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Benoit Pausader, Ph.D., Reader Date Sergei Treil, Ph.D., Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Andrew G. Campbell, Dean of the Graduate School ii Vitae Alexander Barron graduated from Colby College with a B.A. in Mathematics in May 2013 (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa). He also earned an M.S. in mathematics from Brown University in May 2016. At Brown he was a teaching assistant and instructor for multiple sections of Calculus I and II, and also for multivariable calculus. He has given research talks at various conferences and institutions, including Georgia Tech, the University of Virginia, the University of New Mexico, and the American Institute of Math (AIM). Starting in August 2019 he will be serving as a Doob Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois Urbana- Champaign. Below is a list of publications and preprints by the author. 1. Weighted Estimates for Rough Bilinear Singular Integrals via Sparse Domination, N.Y. Journal of Math 23 (2017) 779-811. 2. Sparse bounds for bi-parameter operators using square functions, with Jill Pipher. Preprint arXiv:1709.05009. 3. Sparse domination and the strong maximal function, with Jos´eConde Alonso, Yumeng Ou, and Guillermo Rey. -

A Concentration Inequality and a Local Law for the Sum of Two Random Matrices

Probab. Theory Relat. Fields (2012) 154:677–702 DOI 10.1007/s00440-011-0381-4 A concentration inequality and a local law for the sum of two random matrices Vladislav Kargin Received: 22 November 2010 / Revised: 9 June 2011 / Published online: 7 July 2011 © Springer-Verlag 2011 = + ∗ Abstract Let HN AN UN BN UN where AN and BN are two N-by-N Hermitian μ ,μ ,μ matrices and UN is a Haar-distributed random unitary matrix, and let HN AN BN be empirical measures of eigenvalues of matrices HN , AN , and BN , respectively. Then, it is known (see Pastur and Vasilchuk in Commun Math Phys 214:249–286, 2000) that μ μ for large N, the measure HN is close to the free convolution of measures AN and μ BN , where the free convolution is a non-linear operation on probability measures. μ The large deviations of the cumulative distribution function of HN from its expecta- tion have been studied by Chatterjee (J Funct Anal 245:379–389, 2007). In this paper we improve Chatterjee’s concentration inequality and show that it holds with the rate . , which is quadratic in N In addition, we prove a local law for eigenvalues of HNN by showing that the normalized number of eigenvalues in an interval approaches the density of the free convolution of μA and μB provided that the interval has width (log N)−1/2 . Mathematics Subject Classification (2010) 60B20 · 60B10 · 46L54 1 Introduction If A and B are two Hermitian matrices with a known spectrum, it is a classical problem to determine all possibilities for the spectrum of A+ B. -

Convergence of Optimal Expected Utility for a Sequence of Binomial Models Dedicated to the Memory of Mark Davis

Convergence of Optimal Expected Utility for a Sequence of Binomial Models Dedicated to the memory of Mark Davis Friedrich Hubalek Walter Schachermayer* April 8, 2021 We consider the convergence of the solution of a discrete-time utility max- imization problem for a sequence of binomial models to the Black-Scholes- Merton model for general utility functions. In previous work by D. Kreps and the second named author a counter- example for positively skewed non-symmetric binomial models has been con- structed, while the symmetric case was left as an open problem. In the present article we show that convergence holds for the symmetric case and for negatively skewed binomial models. The proof depends on some rather fine estimates of the tail behaviors of Gaussian random variables. We also review some general results on the convergence of discrete models to Black-Scholes-Merton as developed in a recent monograph by D. Kreps. 1 Introduction Mark Davis has dedicated a large portion of his impressive scientific work to Mathe- matical Finance. He shaped this field by applying masterfully the tools from stochastic analysis which he dominated so well. The present authors remember very well several discussions during Mark's seven months stay in Vienna in 2000. Mark repeatedly expressed his amazement about the perfect match of It^o'sstochastic calculus with the line of Mathematical Finance initiated by Black, Scholes, and Merton [BS73, Mer73]. In particular, Mark was astonished how well the martingale representation theorem fits to this theory and loved this connection. He also appreciated the approximation of the Black-Scholes-Merton model by binomial processes as initiated by Cox, Ross, and Rubinstein [CRR79]. -

Minkowski's Linear Forms Theorem in Elementary Function Arithmetic

Minkowski's Linear Forms Theorem in Elementary Function Arithmetic Author: Greg Knapp Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Mathematics, Applied Mathematics, and Statistics Case Western Reserve University August, 2017 1 Case Western Reserve University Department of Mathematics, Applied Mathematics, and Statistics We hereby approve the thesis of Greg Knapp Candidate for the degree of Master of Science Committee Chair Colin McLarty Committee Member Mark Meckes Committee Member David Singer Committee Member Elisabeth Werner Date of Defense: 27 April, 2017 2 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Elementary Function Arithmetic 4 3. Finite Set Theory and Basic Mathematics in EFA 8 4. Convex Geometry 10 4.1. Weyl's Theorem . 10 4.2. Polytopes and Their Representations . 16 4.2.1. Inequality Representation . 16 4.2.2. Full Information Representation . 19 4.2.3. Intersecting Polytopes . 23 4.3. Triangulations and Volume . 23 4.3.1. Triangulations and Volumes of Simplices . 23 4.3.2. Triangulations and Volumes of Polytopes . 31 4.3.3. Triangulation and Volume of the Cube . 39 5. Minkowski's Linear Forms Theorem 43 6. Acknowledgments 50 References 51 3 Minkowski's Linear Forms Theorem in Elementary Function Arithmetic Abstract by Greg Knapp A classical question in formal logic is \how much mathematics do we need to know in order to prove a given theorem?" Of particular interest is Harvey Friedman's grand conjecture: that every known mathematical theorem involving only finitary mathematical objects can be proven from Elementary Function Arithmetic (EFA)|a fragment of Peano Arithmetic. If Friedman's conjecture is correct, this would imply that Fermat's Last Theorem is derivable from the axioms of EFA. -

Table of Inequalities in Elliptic Boundary Value Problems

Table of inequalities in elliptic boundary value problems C. Bandle, M. Flucher Version April 30, 1997 Contents 1 Introduction and notation 1 2 LP-spaces 4 3 Convergence theorems in LP 7 4 Sobolev spaces 8 5 Critical Sobolev embeddings 11 6 Maximum and comparison principles 13 7 Elliptic regularity theory 14 8 further integral inequalities for solutions of elliptic differential equations 17 9 Calculus of variations 18 10 Compactness theorems 19 11 Geometric isoperimetric inequalities 20 12 Symmetrization 21 13 Inequalities for eigenvalues 23 AMS Subject Classification Code: 35J 1 Introduction and notation This contribution contains a compiled list of inequalities that are frequently used in the calculus of variations ·and elliptic boundary value problems. The selection reflects the authors personal taste and experience. Purely one dimensional results are omitted. o proofs are given. For those we refer e.g. to [71, 71]. Frequently we refer to textbooks rather than original sources. General references are Polya and Szego [88], Morrey [73], Giaquinta [40, 41], Gilbarg and Trudinger [43], Kufner, John and Fucik [61], Ziemer [113]. We hope that this table will be useful to other mathematicians working in these fields and a stimulus to study some of the subjects more deeply. A postscript file of this text is available at the WWW site http://www .rnath. uni bas. ch/-flucher/. It is periodically updated an improved based on suggestions made by users. If your favourite inequality is missing or if you find any unprecise statement, please let us know. Other users will be grateful. 1 BANDLE, FLUCHER: TABLE OF INEQUALITIES 2 1.1 Notation Unless otherwise stated D is a bounded, connected domain in IRn with Lipschitz boundary. -

Identification of the Distribution of Valuations in an Incomplete Model of English Auctions

Identification of the distribution of valuations in an incomplete model of English auctions Andrew Chesher Adam Rosen The Institute for Fiscal Studies Department of Economics, UCL cemmap working paper CWP30/15 Identification of the Distribution of Valuations in an Incomplete Model of English Auctions Andrew Chesher and Adam M. Rosen CeMMAP and UCL June 26, 2015 Abstract An incomplete model of English auctions with symmetric independent private values, similar to the one studied in Haile and Tamer (2003), is shown to fall in the class of Generalized Instrumental Variable Models introduced in Chesher and Rosen (2014). A characterization of the sharp identified set for the distribution of valuations is thereby obtained and shown to refine the bounds available until now. Keywords: English auctions, partial identification, sharp set identification, generalized in- strumental variable models. 1 Introduction The path breaking paper Haile and Tamer (2003) (HT) develops bounds on the common distribution of valuations in an incomplete model of an open outcry English ascending auction in a symmetric independent private values (IPV) setting. One innovation in the paper was the use of an incomplete model based on weak plausible restrictions on bidder behavior, namely that a bidder never bids more than her valuation and never allows an opponent to win at a price she is willing to beat. An advantage of an incomplete model is that it does not require specification of the mechanism relating bids to valuations. Results obtained using the incomplete model are robust to misspecification of such a mechanism. The incomplete model may be a better basis for empirical work than the button auction model of Milgrom and Weber (1982) sometimes used to approximate the process delivering bids in an English open outcry auction. -

Identification of the Distribution of Valuations in An

Identification of the Distribution of Valuations in an Incomplete Model of English Auctions Andrew Chesher and Adam Rosen 13th February 2015 Abstract An incomplete model of English auctions with symmetric indepen- dent private values, similar to the one studied in Haile and Tamer (2003), is shown to fall in the class of Generalized Instrumental Vari- able Models introduced in Chesher and Rosen (2014). A characteri- zation of the sharp identified set for the distribution of valuations is thereby obtained and shown to refine the bounds available until now. Keywords: English auctions, partial identification, sharp set iden- tification, generalized instrumental variable models. 1 Introduction The path breaking paper Haile and Tamer (2003) (HT) develops bounds on the common distribution of valuations in an incomplete model of an open outcry English ascending auction in a symmetric independent private values setting. One innovation in the paper was the use of an incomplete model based on weak plausible restrictions on bidder behaviour, namely that a bidder never bids more than her valuation and never allows an opponent to win at a price she is willing to beat. An advantage of an incomplete model is that it does not require specification of the mechanism relating bids to valuations. Results obtained using the incomplete model are robust to misspecification of such a mechanism. The incomplete model may be a better basis for empirical work than the button auction model of Milgrom and Weber (1982) sometimes used to approximate the process delivering bids in an English open outcry auction. 1 On the down side the incomplete model is partially, not point, identifying for the primitive of interest, namely the common conditional probability distribution of valuations given auction characteristics. -

Approximating the Permanent with Fractional Belief Propagation

Approximating the Permanent with Fractional Belief Propagation The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Chertkov, Michael, and Adam B. Yedidia. “Approximating the Permanent with Fractional Belief Propagation.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 14 (2013): 2029–2066. As Published http://jmlr.org/papers/volume14/chertkov13a/chertkov13a.pdf Publisher Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/81423 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. JournalofMachineLearningResearch14(2013)2029-2066 Submitted 7/11; Revised 1/13; Published 7/13 Approximating the Permanent with Fractional Belief Propagation Michael Chertkov [email protected] Theory Division & Center for Nonlinear Studies Los Alamos National Laboratory Los Alamos, NM 87545, USA Adam B. Yedidia∗ [email protected] Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139, USA Editor: Tony Jebara Abstract We discuss schemes for exact and approximate computations of permanents, and compare them with each other. Specifically, we analyze the belief propagation (BP) approach and its fractional belief propagation (FBP) generalization for computing the permanent of a non-negative matrix. Known bounds and Conjectures are verified in experiments, and some new theoretical relations, bounds and Conjectures are proposed. The fractional free energy (FFE) function is parameterized by a scalar parameter γ [ 1;1], where γ = 1 corresponds to the BP limit and γ = 1 corresponds to the exclusion principle∈ (but− ignoring perfect− matching constraints) mean-field (MF) limit.