Abstract a Long-Time Performer with the Mark Morris Dance Group, I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics

Smith ScholarWorks Dance: Faculty Publications Dance 6-24-2013 “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs Part of the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Tomé, Lester, "“Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics" (2013). Dance: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/dan_facpubs/5 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Dance: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] POSTPRINT “Music in the Blood”: Performance and Discourse of Musicality in Cuban Ballet Aesthetics Lester Tomé Dance Chronicle 36/2 (2013), 218-42 https://doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2013.792325 This is a postprint. The published article is available in Dance Chronicle, JSTOR and EBSCO. Abstract: Alicia Alonso contended that the musicality of Cuban ballet dancers contributed to a distinctive national style in their performance of European classics such as Giselle and Swan Lake. A highly developed sense of musicality distinguished Alonso’s own dancing. For the ballerina, this was more than just an element of her individual style: it was an expression of the Cuban cultural environment and a common feature among ballet dancers from the island. In addition to elucidating the physical manifestations of musicality in Alonso’s dancing, this article examines how the ballerina’s frequent references to music in connection to both her individual identity and the Cuban ballet aesthetics fit into a national discourse of self-representation that deems Cubans an exceptionally musical people. -

Preparing Musicians Making New Sound Worlds

PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Compiled by Orlando Musumeci PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Proceedings of the SEMINAR of the COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya – Barcelona – SPAIN 5-9 JULY 2004 Compiled by Orlando Musumeci Published by the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya Catalan texts translated by Mariam Chaib Babou (except for Rosset i Llobet) Spanish texts translated by Orlando Musumeci (except for Estrada, Mauleón and Rosset i Llobet) Copyright © ISME. All rights reserved. Requests for reprints should be sent to: International Society for Music Education ISME International Office P.O. Box 909 Nedlands 6909, WA, Australia T ++61-(0)8-9386 2654 / F ++61-(0)8-9386-2658 [email protected] ISBN: 0-9752063-2-X ISME COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN DIANA BLOM [email protected] University of Western Sydney – AUSTRALIA PHILEMON MANATSA [email protected] Morgan Zintec – ZIMBABWE ORLANDO MUSUMECI (Chair) [email protected] Institute of Education – University of London – UK Universidad de Quilmes – Universidad de Buenos Aires – Conservatorio Alberto Ginastera – ARGENTINA INOK PAEK [email protected] University of Sheffield – UK VIGGO PETTERSEN [email protected] Stavanger University College – NORWAY SUSAN WHARTON CONKLING [email protected] Eastman School of Music – USA GRAHAM BARTLE (Special Advisor) [email protected] -

The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Dance Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Tania, "The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1118. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1118 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores Occidental College Migration and Transnational Identity: Fall 2011 Flores 2 Acknowledgments I could not have completed this project without the advice and guidance of my academic director, Professor Souad Eddouada; my advisor, Professor Taieb Belghazi; my professor of music at Occidental College, Professor Simeon Pillich; my professor of Islamic studies at Occidental, Professor Malek Moazzam-Doulat; or my gracious and helpful interviewees. I am also grateful to Elvira Roca Rey for allowing me to use her studio to choreograph after we had finished dance class, and to Professor Said Graiouid for his guidance and time. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Rebranding Initiative

REBRANDING INITIATIVE Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. History and Summary of Issues. 2. Review of Strengths and Weaknesses. 3. Suggested Actions Organized in the Following Categories: a. Board Structure b. Administrative Structure c. Financial d. Choir Structure and Performances e. Marketing 4. Current Mission and Vision Statements Page 2 HISTORY AND SUMMARY OF ISSUES The San Antonio Choral Society began in 1964. It’s original purpose was to provide a community based choir that would be large enough to sing master works and more difficult works than most church choirs could perform. The choir drew members from all over San Antonio (mostly from church choirs) and was an instant success. SACS continued in that mode until the 1990’s when the repertoire was expanded to include more popular music. In 1996, Broadway musicals were added for a “Pops” concert. The choir continued to be managed by a group of charter members until 2013 when a large number of charter members retired from the choir. At that time Jennifer Seighman was hired to be the artistic director for the choir. Jennifer began to raise the standard in terms of music quality, performance arrangement, singer’s skills and music education. Everyone enjoyed the new challenge. In addition, in 2014 the choir was the beneficiary of sizable funds from the estate of a deceased member that continued through 2016. Those funds have now ceased leaving the choir in a quandary as to how to deal with increased costs of operations and no clearly defined revenue source. The loss of funds has caused the officers to reassess our current situation and try to project what direction is needed for the future. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Danc-Dance (Danc) 1

DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 DANC 1131. Introduction to Ballroom Dance DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 Credit (1) Introduction to ballroom dance for non dance majors. Students will learn DANC 1110G. Dance Appreciation basic ballroom technique and partnering work. May be repeated up to 2 3 Credits (3) credits. Restricted to Las Cruces campus only. This course introduces the student to the diverse elements that make up Learning Outcomes the world of dance, including a broad historic overview,roles of the dancer, 1. learn to dance Figures 1-7 in 3 American Style Ballroom dances choreographer and audience, and the evolution of the major genres. 2. develop rhythmic accuracy in movement Students will learn the fundamentals of dance technique, dance history, 3. develop the skills to adapt to a variety of dance partners and a variety of dance aesthetics. Restricted to: Main campus only. Learning Outcomes 4. develop adequate social and recreational dance skills 1. Explain a range of ideas about the place of dance in our society. 5. develop proper carriage, poise, and grace that pertain to Ballroom 2. Identify and apply critical analysis while looking at significant dance dance works in a range of styles. 6. learn to recognize Ballroom music and its application for the 3. Identify dance as an aesthetic and social practice and compare/ appropriate dances contrast dances across a range of historical periods and locations. 7. understand different possibilities for dance variations and their 4. Recognize dance as an embodied historical and cultural artifact, as applications to a variety of Ballroom dances well as a mode of nonverbal expression, within the human experience 8. -

State High School Dance Festival 2014 – BYU Adjudicator and Master Class Teacher Bios

Utah Dance Education Organization State High School Dance Festival 2014 – BYU Adjudicator and Master Class Teacher Bios Kay Andersen received his Master of Arts degree at New York University. He resided in NYC for 15 years. From 1985-1997 he was a soloist with the Nikolais Dance Theatre and the Murray Louis Dance Company. He performed worldwide, participated in the creation of important roles, taught at the Nikolais/Louis Dance Lab in NYC and presented workshops throughout the world. At Southern Utah University he choreographs, teaches improvisation, composition, modern dance technique, tap dance technique, is the advisor of the Orchesis Modern Dance Club, and serves as Chair of the Department of Theatre Arts and Dance. He has choreographed for the Utah Shakespearean Festival and recently taught and choreographed in China, the Netherlands, Mexico, North Carolina School of the Arts, and others. Kay Andersen (SUU) Ashley Anderson is a choreographer based in Salt Lake City. Her recent work has been presented locally at the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center, the Rio Gallery, the BYU Museum of Art, Finch Lane Gallery, the City Library, the Utah Heritage Foundation’s Ladies’ Literary Club, the Masonic Temple and Urban Lounge as well as national venues including DraftWork at Danspace Project, BodyBlend at Dixon Place, Performance Mix at Joyce SOHO (NY); Mascher Space Cooperative, Crane Arts Gallery, the Arts Bank (PA); and the Taubman Museum of Art (VA), among others. Her work was also presented by the HU/ADF MFA program at the American Dance Festival (NC) and the Kitchen (NY). She has recently performed in dances by Ishmael Houston-Jones, Regina Rocke & Dawn Springer. -

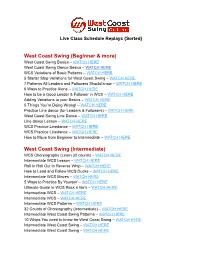

West Coast Swing (Beginner & More)

Live Class Schedule Replays {Sorted} West Coast Swing (Beginner & more) West Coast Swing Basics – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Dance Basics – W ATCH HERE WCS Variations of Basic Patterns – W ATCH HERE 5 Starter Step Variations for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE 7 Patterns All Leaders and Followers Should know – W ATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice Alone – WATCH HERE How to be a Good Leader & Follower in WCS – WATCH HERE Adding Variations to your Basics – W ATCH HERE 5 Things You’re Doing Wrong! – WATCH HERE Practice Line dance (for Leaders & Followers) – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Line Dance – WATCH HERE Line dance Lesson – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE How to Move from Beginner to Intermediate – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing (Intermediate) WCS Choreography (Learn 32 counts) – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Lesson – WATCH HERE Roll In Roll Out to Reverse Whip – WATCH HERE How to Lead and Follow WCS Ducks – W ATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Moves – WATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice By Yourself – WATCH HERE Ultimate Guide to WCS Rock n Go’s – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Patterns – WATCH HERE 32 Counts of Choreography (Intermediate) – W ATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing Patterns – WATCH HERE 10 Whips You need to know for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing ( Advanced) Advanced WCS Moves – WATCH HERE -

Nightclub Two-Step (Club Two-Step, NC2S)

Nightclub Two-Step (Club Two-Step, NC2S) Richard Powers Buddy Schwimmer developed this dance in the late 1970s and it has become widely popular among American social dancers. It is the perfect dance for easygoing, moderate-tempo music, and provides a welcome break between fast dances. It can be danced in a wide range of tempos, from 72 to 92 beats per minute, with 82 bpm as its sweet spot. Buddy Schwimmer originally taught Nightclub Two-Step as rock-step first, danced in quick-quick-slow timing. Today dancers accept both slow-quick-quick or quick-quick-slow timings, depending on what the music indicates. We teach it in the slow-quick-quick timing for two reasons. 1) This timing feels more musical, especially for the Follow role, letting her dance the strongest movements at the strongest moment in the music, on count 1. When the music goes, the Follow goes, instead of being delayed by a rock step. 2) This timing is more commonly done in the Bay Area, and we want our students here to dance comfortably with most local dancers. But we don't dismiss the other timing. They're both good. You'll probably want to adopt the timing done by most dancers in your area. The Basic Step Take a relaxed closed dance position. Count 1 The Lead takes a slow step to the left side with his left foot as the Follow steps side right. 2 The Lead rocks his right foot behind his left heel, taking weight on the ball of his right foot, as the Follow rocks back left. -

Nelisiwe Xaba

Nelisiwe Xaba Special Section Guest Editor Susan Manning Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram_a_00912 by guest on 28 September 2021 Nelisiwe Xaba Dancing between South Africa and the Global North Susan Manning The cluster of essays in this issue of TDR provides a range of responses to the work of Nelisiwe Xaba, a South African performer and choreographer who often receives commissions and tours in the Global North. Her work forms part of the rich landscape of dance and the- atre in postapartheid South Africa as well as part of the dynamic scene of contemporary dance across Africa.1 Yet she resists the rubric of “contemporary African dance,” for she believes that too often European and North American presenters use this rubric to isolate contempo- rary artists in Africa from their peers on the global stage. In fact, Xaba’s work constantly asks exactly what expectations spectators, inside and outside South Africa, bring to their encounters with contemporary performance. Born in 1970, Xaba grew up in Soweto and started dancing “during the political uprisings in the late 1980s [...] when formal schooling in Soweto was interrupted, when the youth were riot- ing.” She danced to “find something constructive [...,] a way of getting out of the streets” (in Piccirillo 2011:70). At the Johannesburg Dance Foundation for four years, Xaba studied bal- let, Graham technique, Horton technique, jazz, and gymnastics. In 1991–92 she toured the US with the South African company Soweto Street Beat, and so she arrived in the US as a 21-year- old who “had never lived alone, or had to sort out my life on my own.” She experienced intense culture shock. -

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality by Martha Edwards In this article, I’m going to talk about a simple thing that you can do to make you, your band mates, and your dance community fall in love with the music that you make. It’s called phrasing. Yup, phrasing. Musical phrasing is a lot like verbal phrasing. Sentences start somewhere and end somewhere, just like music. Sometimes they start soft, and grow and grow until they END! SOMETIMES they start big and taper off at the end. Sometimes they grow and get BIG and then taper off at the end. But a lot of people never notice that music does the same thing, that it comes from somewhere and goes somewhere. When you help it do that, you’re really sending a musical experience to your audience. Otherwise, you’re just typing. What do I mean by typing? I mean that, if all you do is play the notes, one after another, at the same intensity from beginning to end, you could play the notes perfectly, but your playing would be boring. You wouldn’t be shaping the phrase, you would just be sending out a kind of telegraph message with no emotion attached. I think it happens because playing music is hard, and it’s a big challenge just to be able to play the notes of a tune at all. When you finally get the notes of a tune, one after another, it’s a kind of victory. But don’t stop with just the notes. Learn to play musically! photo of Miranda Arana, Jonathan Jensen and Martha Edwards (courtesy Childgrove Country Dancers, St.