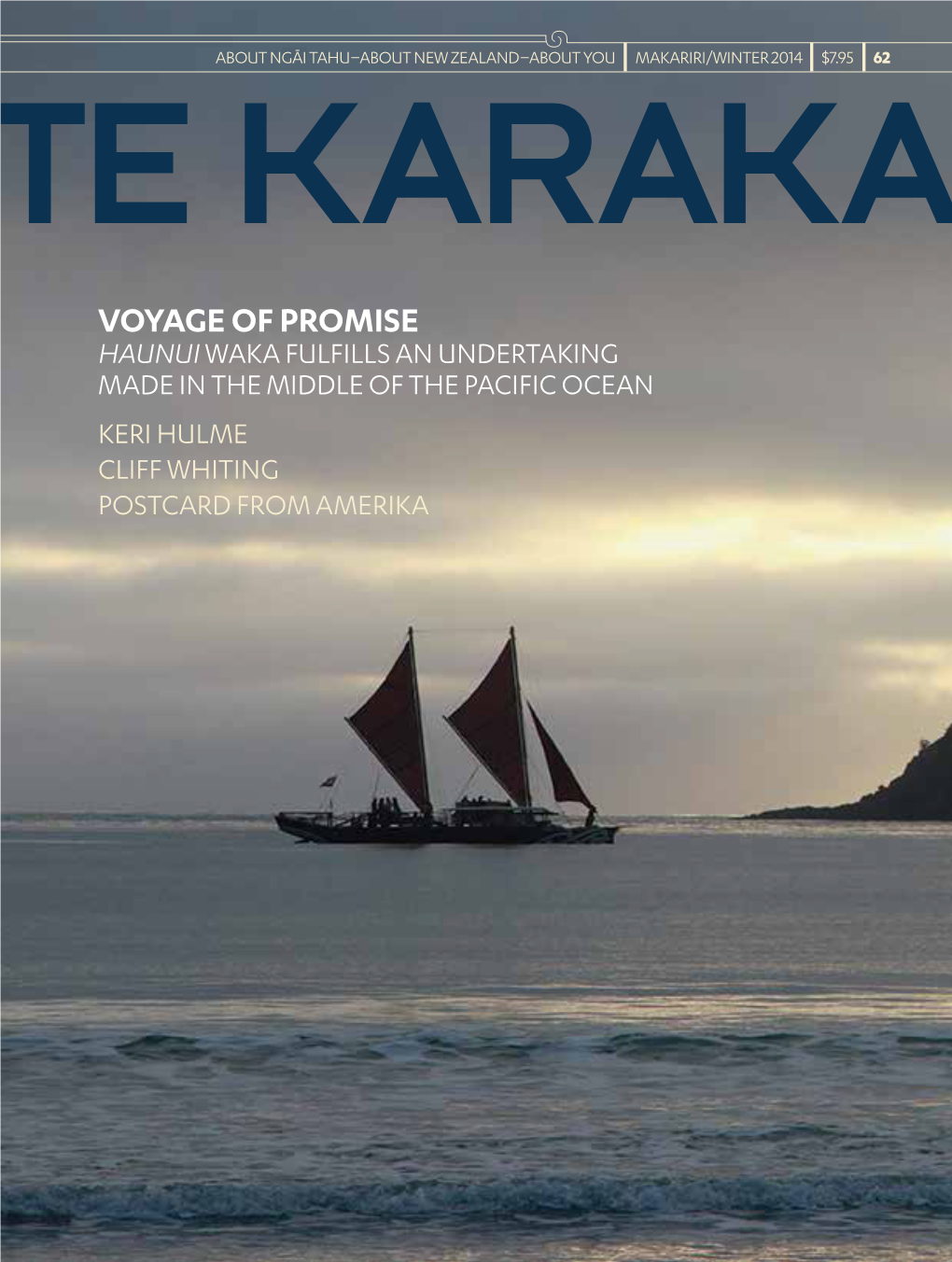

Voyage of Promise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Britos

PETER BRITOS A Conversation with Merata Mita This conversation took place on January 15th 2003 at about 8pm in Honolulu. We met at Merata’s home offi ce near the campus where her youngest son Hepi is fi nishing up his high school studies. Hepi met me downstairs and escorted me to his mother’s study, where Merata was working on a book about her life experiences. PB: My mother once told me that the cool thing about talking is that sometimes you don’t know a thing existed until you say it. The mere physicality of the act brings you to a place that you couldn’t have gotten to any other way. MM: I’ve known things. And until I’ve articulated them, they’ve never been con- scious. I like the experience of new places and new things and working out how to survive in different environments that are totally dif- ferent ones than I’m used to. But until you articulate that survival, it’s just living. Geoff [Murphy—her producer/director husband] never sees those challenges as being pleas- ant. But I thrive on that sort of thing. In the end I had to agree with him that we should move from Los Angeles. But I didn’t know where, and didn’t really care. And he always had in his mind that the ideal halfway point between Los Angeles and New Zealand would be Hawai`i. So I said aah Polynesians, hmmm. Okay. So we ended up here and he could make whatever film he was making. -

2019 Annual Report

New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata Annual Report 2019 1 Chair’s Introduction On behalf of the Trustees and Management Board of the New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata, it is my pleasure to present our Annual Report for 2019. Nick Cuthell, Portrait of Dr Alan Bollard. 2012. Collection, Reserve Bank of New Zealand. This is my first report to you as Chair, We are very grateful to all the artists and I am delighted to confirm the and curators for their work in bringing Gallery is in good heart despite the these remarkable exhibitions to the financial challenges we continue to Gallery. face. We are also very grateful to our The year’s exhibition programme has sponsors for their backing of this been a resounding success – from year’s programme. Without them John Walsh’s stunning Portrait of our exhibitions would not have been Ūawa Tolaga Bay with its massive possible. Special thanks must be mural of an East Coast community given to Chris and Kathy Parkin whose to the three innovative and diverse generosity provided a professional exhibitions which followed. The publicist to promote our exhibitions. range of experience represented As a result, visitor numbers are by these exhibitions, as well as running almost 6% ahead of last year. the small exhibitions in the front Our loyal Friends and supporters have gallery, encapsulate our evolving also continued to champion projects understanding of ourselves as New to improve the Gallery’s facilities, and Zealanders, our history and creativity. the Director and her team continue to 2 Cover image: Opening of Being Chinese in Aotearoa exhibition, 20 November 2019. -

This Action Thriller Futuristic Historic Romantic Black Comedy Will Redefine Cinema As We Know It

..... this action thriller futuristic historic romantic black comedy will redefine cinema as we know it ..... XX 200-6 KODAK X GOLD 200-6 OO 200-6 KODAK O 1 2 GOLD 200-6 science-fiction (The Quiet Earth) while because he's produced some of the Meet the Feebles, while Philip Ivey composer for both action (Pitch Black, but the leading lady for this film, to Temuera Morrison, Robbie Magasiva, graduated from standing-in for Xena beaches or Wellywood's close DIRECTOR also spending time working on sequels best films to come out of this country, COSTUME (Out of the Blue, No. 2) is just Daredevil) and drama (The Basketball give it a certain edginess, has to be Alan Dale, and Rena Owen, with Lucy to stunt-doubling for Kill Bill's The proximity to green and blue screens, Twenty years ago, this would have (Fortress 2, Under Siege 2) in but because he's so damn brilliant. Trelise Cooper, Karen Walker and beginning to carve out a career as a Diaries, Strange Days). His almost 90 Kerry Fox, who starred in Shallow Grave Lawless, the late great Kevin Smith Bride, even scoring a speaking role in but there really is no doubt that the been an extremely short list. This Hollywood. But his CV pales in The Lovely Bones? Once PJ's finished Denise L'Estrange-Corbet might production designer after working as credits, dating back to 1989 chiller with Ewan McGregor and will next be and Nathaniel Lees as playing- Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof. South Island's mix of mountains, vast comes down to what kind of film you comparison to Donaldson who has with them, they'll be bloody gorgeous! dominate the catwalks, but with an art director on The Lord of the Dead Calm, make him the go-to guy seen in New Zealand thriller The against-type baddies. -

2.2 the MONARCHY Republican Sentiment Among New Zealand Voters, Highlighting the Social Variables of Age, Gender, Education

2.2 THE MONARCHY Noel Cox and Raymond Miller A maturing sense of nationhood has caused some to question the continuing relevance of the monarchy in New Zealand. However, it was not until the then prime minister personally endorsed the idea of a republic in 1994 that the issue aroused any significant public interest or debate. Drawing on the campaign for a republic in Australia, Jim Bolger proposed a referendum in New Zealand and suggested that the turn of the century was an appropriate time symbolically for this country to break its remaining constitutional ties with Britain. Far from underestimating the difficulty of his task, he readily conceded that 'I have picked no sentiment in New Zealand that New Zealanders would want to declare themselves a republic'. 1 This view was reinforced by national survey and public opinion poll data, all of which showed strong public support for the monarchy. Nor has the restrained advocacy for a republic from Helen Clark, prime minister from 1999, done much to change this. Public sentiment notwithstanding, a number of commentators have speculated that a New Zealand republic is inevitable and that any move in that direction by Australia would have a dramatic influence on public opinion in New Zealand. Australia's decision in a national referendum in 1999 to retain the monarchy raises the question of what effect, if any, that decision had on opinion on this side of the Tasman. In this chapter we will discuss the nature of the monarchy in New Zealand, focusing on the changing role and influence of the Queen's representative, the governor-general, together with an examination of some of the factors that might have an influence on New Zealand becoming a republic. -

The Interface Between Aboriginal People and Maori/Pacific Islander Migrants to Australia

CUZZIE BROS: THE INTERFACE BETWEEN ABORIGINAL PEOPLE AND MAORI/PACIFIC ISLANDER MIGRANTS TO AUSTRALIA By James Rimumutu George BA (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Newcastle March 2014 i This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: Date: ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors, Professor John Maynard and Emeritus Professor John Ramsland for their input on this thesis. Professor Maynard in particular has been an inspiring source of support throughout this process. I would also like to give my thanks to the Wollotuka Institute of Indigenous Studies. It has been so important to have an Indigenous space in which to work. My special thanks to Dr Lena Rodriguez for having faith in me to finish this thesis and also for her practical support. For my daughter, Mereana Tapuni Rei – Wahine Toa – go girl. I also want to thank all my brothers and sisters (you know who you are). Without you guys life would not have been so interesting growing up. This thesis is dedicated to our Mum and Dad who always had an open door and taught us to be generous and to share whatever we have. -

Debate Recovery? Ch

JANUARY 16, 1976 25 CENTS VOLUME 40/NUMBER 2 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE actions nee - DEBATE U.S. LEFT GROUPS DISCUSS VITAL ISSUES IN REVOLUTION. PAGE 8. RECOVERY? MARXIST TELLS WHY ECONOMIC UPTURN HAS NOT BROUGHT JOBS. PAGE 24. RUSSELL MEANS CONVICTED IN S.D. FRAME-UP. PAGE 13. Original murder charges against Hurricane Carter stand exposed and discredited. Now New Jersey officials seek to keep him' behind bars on new frame-up as 'accomplice/ See page 7. PITTSBURGH STRIKERS FIGHT TO SAVE SCHOOLS. PAGE 14. CH ACTION TO HALT COP TERROR a Ira me- IN NATIONAL CITY. PAGE 17. In Brief NO MORE SHACKLES FOR SAN QUENTIN SIX: The lation that would deprive undocumented workers of their San Quentin Six have scored a victory with their civil suit rights. charging "cruel and unusual punishment" in their treat The group's "Action Letter" notes, "[These] bills are ment by prison authorities. In December a federal judge nothing but the focusing on our people and upon all Brown THIS ordered an end to the use of tear gas, neck chains, or any and Asian people's ability to obtain and keep a job, get a mechanical restraints except handcuffs "unless there is an promotion, and to be able to fight off discrimination. But imminent threat of bodily harm" for the six Black and now it will not only be the government agencies that will be WEEK'S Latino prisoners. The judge also expanded the outdoor qualifying Brown people as to whether we have the 'right' to periods allowed all prisoners in the "maximum security" be here, but every employer will be challenging us at every MILITANT Adjustment Center at San Quentin. -

Feilding Public Library Collection

Object ID Begins with "2009.102" 14/06/2020 Matches 4033 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location P 2009.102.01.01 Manchester Street School, Feilding. Primer 2-3 1939. Grouped Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive against a fence with trees and houses in the background. Print, Photographic Front Row L to R: eighth girl - Betty Doughty, last girl - June Wells. P 2009.102.01.02 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School Std 4 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.03 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School F 1-2 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.04 Studio photo Manchester Street School Basketball A Team 1939 Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.05 Manchester Street School Basketball B Team 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.06 Manchester Street School Prefects 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.07 Manchester Street School 1st XV 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.08 Manchester Street School Special Class 1940 Grouped against a Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive fence with trees and houses in the background Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.09 Manchester Street School -

2009 Annual Report

2009 WIDER IMPACT, COMMUNITY CONTRIBUTION New Zealand’s Mäori Centre of Research Excellence www.maramatanga.ac.nz ISSN 1176-8622 © Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga New Zealand’s Mäori Centre of Research Excellence CONTACTS ko te pae tawhiti Postal Address Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga arumia kia tata Waipapa Marae Complex The University of Auckland ko te pae tata whakamaua Private Bag 92019 Auckland Mail Centre kia puta i te wheiao Auckland 1142 New Zealand ki te ao märama Physical Address Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga seek to bring the Rehutai Building 16 Wynyard Street distant horizon closer The University of Auckland Auckland but the closer horizon, grasp it New Zealand so you may emerge from darkness www.maramatanga.ac.nz [email protected] into enlightenment T +64 9 373 7599 ext 84220 F +64 9 373 7928 2009 HIGHLIGHTS 2009 saw many successes in delivering on the CoRE’s vision for positive social transformation, including: Publication of five academic journals of Mäori and indigenous writing, 41 peer-reviewed articles, 13 research reports, three book chapters and 65 conference papers or presentations Continued promotion of greater Mäori involvement in science with the launch of science monograph Te Ara Pütaiao – Mäori Insights in Science, prompting wide media and community interest in Mäori achievements, challenges and opportunities to contribute more fully to scientific advances The launch of our largest research programme, focusing on achieving research outcomes with long term benefits and confirmation of high-calibre independent advisory boards -

JACQUELINE FAHEY B. 1929, Timaru

GOW LANGSFORD GALLERY JACQUELINE FAHEY b. 1929, Timaru Jaqueline Fahey’s paintings collide portraiture with suburban landscapes to create riotously colourful compositions that revel in the chaos of domesticity. Married and a mother to three early in her painting career, the stifling gendered society of 1950s and 1960s New Zealand saw Fahey adopt unconventional colour, technique, and subject matter to reflect and actively challenge the status quo of the gender divide. Yet embedded in the artist’s pugnacious approach is a great level of affection for the women and relationships portrayed, evident in the careful detail bestowed on traditionally ‘female’ interests – clothing, interior textiles, bouquets- elevating the decorative female space above the austere settings more familiar to portraiture. Her distinctive painting style is recognisable for a raucous use of colour, with often haphazard use of perspectival space to force the viewer into the claustrophobia of the female experience. You can hear Fahey’s paintings. Expertly realised portraits are candid in their expressions – characters are shown mouth open, mid argument, or gazing off absentmindedly into the distance. Glimpses of TV sets, record players, and radios are combined with closely observed wine glasses, cups of tea, and bottles of gin. The clamour of crockery and conversation rings through the paintings and spills out into our space as they do into the painted gardens visible through open windows. Later bodies of work see Fahey applying her distinctive flare to urban environments and urban characters; translating domestic politics to their manifestation in the public environment. Born in Timaru in 1929, Fahey began her painting education in earnest at sixteen, at the Canterbury College School of Art, now Ilam. -

(No. 23)Craccum-1976-050-023.Pdf

A u rb la n d University Student Paper to make these points at all. He was In April and May of 197 2 the obviously sensitive about the fact short-lived Sunday Herald ran a that his articles conflicted with the series of four articles dealing with official fiction that ours is a classless the men who dominate New Zealand society, and was trying to salvage as commerce. The first article was much of the myth as possible. headed Elite Group has Reins on The formation of oligarchies Key Directorships, and it justified is a strong New Zealand characterist this title with the contention that ic - it doesn’t only happen in the “a large proportion of private assets business world. The situation could in New Zealand are under the almost be described as ‘Government control of a group which probably m M m by In-group’. This characteristic is numbers less than 300 people. more costy than sinister - not that Control of commerce in New it makes any difference. The effect Zealand seems to be exercised is more important than the motive, through large companies which have and the effect in this case is that the interlocking directorates. It is country is suffocating under the possible to construct a circular uninspired direction of a number of chain which leads from point A little in-groups. Practically every right through the economy back to institution and organisation in New point A.” W EALTH Zealand - whether it be a university The anonymous author selected administration or a students’ a company at random - New association, Federated Farmers or Zealand Breweries - and listed the the Federation of Labour - is run by connections that its directors had POWER with other companies. -

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award Crafting Aotearoa: Protest Tautohetohe: A Cultural History of Making Objects of Resistance, The New Zealand Book Awards Trust has immense in New Zealand and the Persistence and Defiance pleasure in presenting the 16 finalists in the 2020 Wider Moana Oceania Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams, Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, the country’s Puawai Cairns Karl Chitham, Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Published by Te Papa Press most prestigious awards for literature. Damian Skinner Published by Te Papa Press Bringing together a variety of protest matter of national significance, both celebrated and Challenging the traditional categorisations The Trust is so grateful to the organisations that continue to share our previously disregarded, this ambitious book of art and craft, this significant book traverses builds a substantial history of protest and belief in the importance of literature to the cultural fabric of our society. the history of making in Aotearoa New Zealand activism within Aotearoa New Zealand. from an inclusive vantage. Māori, Pākehā and Creative New Zealand remains our stalwart cornerstone funder, and The design itself is rebellious in nature Moana Oceania knowledge and practices are and masterfully brings objects, song lyrics we salute the vision and passion of our naming rights sponsor, Ockham presented together, and artworks to Residential. This year we are delighted to reveal the donor behind the acknowledging the the centre of our influences, similarities enormously generous fiction prize as Jann Medlicott, and we treasure attention. Well and divergences of written, and with our ongoing relationships with the Acorn Foundation, Mary and Peter each. -

Words That Make Worlds. Arguments That Change Minds. Ideas That Illuminate. We Publish Books That Make a Difference

AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY PRESS — 2012 CATALOGUE Words that make worlds. Arguments that change minds. Ideas that illuminate. We publish books that make a difference. Summer 2012 BA: AN INSIDER’S GUIDE Rebecca Jury BA: An Insider’s Guide is the essential book for all those considering study or about to embark on their arts degree. In 10 steps, Jury introduces readers to everything from choosing courses (just like putting together a personalised gourmet sandwich), setting up a study space and doing part-time work to turning up at lectures and tutorials and actually reading readings. In particular, she focuses on planning, work–life balance, study habits, succeeding at essays and exams and sorting out a life afterwards. Recently emerged from the maelstrom of university, Jury offers the inside word on doing well there. Rebecca Jury graduated with a BA (English and Mass Communication) from Canterbury University in 2008. Her grade average was excellent! Since completing her degree she has worked as a university tutor, a youth counsellor and a high-school teacher. February 2012, 190 x 140 mm, 200 pages Paperback, 978 1 86940 577 9, $29.99 2/3 Summer 2012 BEAUTIES OF THE OCTAGONAL POOL Gregory O’Brien In an eight-armed embrace, Beauties of the Octagonal Pool collects poems written from and out of a variety of times, locations and experiences. O’Brien’s poems have a thoughtful musicality, a shambling romance, a sense of humour, an eye on the horizon. On Raoul Island we meet a mechanical rat; on Waiheke, the horses of memory thunder down the course; and in Doubtful Sound, the first guitar music heard in New Zealand spills over the waves .