CURA PERSONALIS in COLLEGE ATHLETICS: a CASE STUDY of STUDENT-ATHLETES at GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY a Thesis Submitted to the Facul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Head in for Success

R SERVING SPORT THROUGH EXCELLENCE IN CHAPLAINCY HEAD IN FOR SUCCESS Supporting the wellbeing of the elite or dedicated athlete and player HEAD IN FOR SUCCESS R SERVING SPORT THROUGH EXCELLENCE IN CHAPLAINCY suPPORTING THE WELLBEING OF THE ELITE OR DEDICATED ATHLETE AND PLAYER Compiled by the Mental Health Foundation & Sports Chaplaincy UK 1 2 INtRODUCtION Their identity was affected as they felt like they were known for their sport rather The aim of this booklet is to highlight potential than as a person. challenges dedicated athletes face and offer guidance and suggestions on how to deal with these stresses. Feeling isolated when they are injured Included in this booklet are tips on how to cope “It would although some felt they coped well with with injuries, how to manage uncertainties and injury. disappointment, and suggestions of healthy strategies definitely be to cope with stresses that arise from sport and life in Coping with uncertainty around selection, something that general and build resilience. This booklet aims to give how they were valued at a club. the reader the knowledge and freedom to look after “people don’t see, they themselves and feel good about it. Many bottle up their emotions. can cope with their Being an elite athlete has many positives, including Most admitted to always trying to look training schedule and keeping fit and active which can lead to many positive even when they don’t feel like it. physical benefits. Additionally, this is coupled with then other things can the enjoyment and purpose of playing your favourite Most feared showing they were not sport, camaraderie and friendship, and the loyalty come in and they coping or looking ‘weak’ emotionally. -

Inspiring Athletes Through Mentorship: a Case Study of a Fellowship of Christian Athletes Chaplaincy Ministry Program

Inspiring Athletes Through Mentorship: A Case Study of a Fellowship of Christian Athletes Chaplaincy Ministry Program by LaTosha Nicole Ramsey A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 12, 2015 Fellowship Christian Athletes, chaplaincy, student athletes, spiritual development, student development, faith development Copyright 2015 by LaTosha Nicole Ramsey Approved by Frances K. Kochan, Chair, Professor Emerita, Educational Foundations, Leadership and Technology Paulette Dilworth, Assistant Vice President, Access & Community Affairs David DiRamio, Associate Professor of Educational Foundations, Leadership and Technology Abstract The Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA) was founded in the 1950s to aid in the spiritual development of middle and high school student athletes. During the late 1990s a paradigm shift occurred when intercollegiate football coaches started to hire full-time team chaplains to become the spiritual coordinators for their student athletes. Athletes across the nation and abroad are recruited by colleges and universities for a variety of sports ranging from football to hockey. These student athletes have basic developmental needs that have to be addressed while they attend college (Hamilton & Sina, Pascarella, 1999). When student athletes arrive on campus, they are often assigned a coordinator to assist with their academic achievement (academic coordinator), life skills development (social, emotional, mental coordinator) and athletic participation (defensive and offensive coordinator). All of these areas aid in meeting their developmental needs. However, the one area that is often neglected is their spiritual development. College is a time when students are searching to find meaning and purpose in their lives (Astin, Astin & Lindholm, 2010; Chickering, Dalton & Stamm, 2006; Parks, 2000). -

Communications Big 12 Championship 19-8 12-6 #11 / #12 46-12 32-8 11 Overall Big 12 Ranking (Ap/Coaches) Big 12 Champ

MARCH 11, 2021 | BIG 12 CHAMPIONSHIP - QUARTERFINALS | GAME NOTES KANSAS COMMUNICATIONS BIG 12 CHAMPIONSHIP 19-8 12-6 #11 / #12 46-12 32-8 11 OVERALL BIG 12 RANKING (AP/COACHES) BIG 12 CHAMP. UNDER BILL SELF BIG 12 CHAMP. TITLES AT Bill Self 520-117 (.816) T-Mobile Center 24-5 (.828) JAYHAWKS HEAD COACH RECORD AT KU, 18TH SEASON 2021 VENUE CHAMP. RECORD AT T-MOBILE CENTER GAME SCHEDULE (H: 13-1; A: 4-6; N: 2-1) KANSAS VS OKLAHOMA / IOWA STATE KU-OSU SERIES AT A GLANCE KU OPP Big 12 Championship • Quarterfinals OVERALL KANSAS LEADS, 151-69 Date Rnk Rnk Opponent TV Time/Result Kansas City, Mo. • T-Mobile Center (18,972) in Big 12 Champ. (T-Mobile Center) Tied, 2-2 (0-0) NOVEMBER (1-1) 28 Thursday, March 11, 2020 • 5:30 p.m. (CT) Last Meeting L, 68-75 @ OU, 1/23/21 26 6/52 1/ Gonzaga% FOX L, 90-102 27 6/5 -/- Saint Joseph’s% FS1 W, 94-72 KU-ISU SERIES AT A GLANCE ESPN / ESPN2 JAYHAWK RADIO NETWORK OVERALL KANSAS LEADS, 186-66 DECEMBER (7-0) Play-by-Play: Bob Wischusen Radio: IMG Jayhawk Radio Network in Big 12 Champ. (T-Mobile Center) Tied, 3-3 (1-3) 1 7/5 20/9 Kentucky# ESPN W, 65-62 Analyst: Fran Fraschilla Webcast: KUAthletics.com/Radio Last Meeting W, 64-50 @ ISU, 2/11/21 3 7/5 -/- WASHBURN B12 NOW W, 89-54 Reporter: Holly Rowe Play-by-Play: Brian Hanni Producer: Scott Gustafson Analyst: Greg Gurley RANKINGS 5 7/5 -/- NORTH DAKOTA ST. -

Terrell Allen Joined the Starting Lineup 11 Games Ago and Has Averaged 10.2 Ppg, 5.5 Apg and 1.4 Spg While Shooting 49.4% (39-79) from the Field

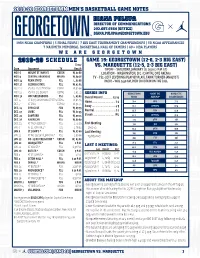

2019-20 GEORGETOWN MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS 202.687.6564 (OFFICE) [email protected] 1984 NCAA CHAMPIONS | 5 FINAL FOURS | 7 BIG EAST TOURNAMENT CHAMPIONSHIPS | 30 NCAA APPEARANCES 7 NAISMITH MEMORIAL BASKETBALL HALL OF FAMERS | 60+ NBA PLAYERS WE ARE GEORGETOWN SCHEDULE GAME 19: GEORGETOWN (12-6, 2-3 BIG EAST) Time/ VS. MARQUETTE (12-5, 2-3 BIG EAST) Date Opponent TV Result TIPOFF – SATURDAY, JANUARY 18, 2020 (2 P.M. ET) NOV. 6 MOUNT ST. MARY’S CBSSN W, 81-68 LOCATION – WASHINGTON, D.C. (CAPITAL ONE ARENA) NOV. 9 CENTRAL ARKANSAS MASN2 W, 89-78 TV – FS1 - JEFF LEVERING (PLAY-BY-PLAY), TARIK TURNER (ANALYST) NOV. 14 PENN STATE ! FS1 L, 81-66 RADIO – WOL 1450 AM, RICH CHVOTKIN ON THE CALL NOV. 17 GEORGIA STATE FS1 W, 91-83 NOV. 21 VS. NO. 22/22 TEXAS # ESPN2 W, 82-66 NOV. 22 VS. NO. 1/1 DUKE # ESPN2 L, 81-73 SERIES INFO GEORGETOWN ABOUT THE MARQUETTE NOV. 30 UNC GREENSBORO FS2 L, 65-61 Overall Record ............. 13-14 HOYAS MATCHUP GOLDEN EAGLES DEC. 4 AT RV/25 OKLAHOMA STATE % ESPN+ W, 81-74 Home ................................ 7-4 79.0 PPG 77.2 DEC. 7 AT SMU ESPNU W, 91-74 Away ................................ 4-9 73.1 OPP PPG 67.9 DEC. 14 SYRACUSE FOX W, 89-79 DEC. 17 UMBC FS1 W, 81-55 Neutral ............................. 2-1 45.7 FG% 42.9 DEC. 21 SAMFORD FS1 W, 99-71 Streak .............................. W1 42.1 OPP FG% 38.9 DEC. 28 AMERICAN FS1 W, 80-60 113 3PM 168 DEC. -

Sport Psychology, Chaplaincy & Faith Working

Sports Chaplaincy UK presents a one day conference SPORT PSYCHOLOGY, CHAPLAINCY & FAITH WORKING TOGETHER FOR WELL-BEING & PERFORMANCE Hosted by: Thursday St Mary’s University, Cost 20th April 2017 Twickenham, London £25 Yes, I’d like to support the work of Sports Chaplaincy PROGRAMME FOR DAY 9.00 Registration INTRODUCTION 9.45 Welcome Vladimir Felzmann; JP2F4S & St. Mary’s University Sport Psychology, Chaplaincy & Faith: Working Together for Well-being &Performance Introduction Warren Evans, SCUK Thursday 20th April, 2017 10.00 Matt Baker: The prevalence of faith in football Shannon Conference Suite; St. Mary’s University, Strawberry Hill, Twickenham. Linvoy Primus: A player’s perspective on the influence of faith on well-being and performance There is growing literature examining links between spirituality and sport 11.15 Break/refreshments psychology and there are now a growing number of Latin American, European, African and British athletes where faith is central in their culture and lives. There 11.45 Mark Nesti: Sport Psychology in the English Premier League: is a need for sport psychologists to better understand the relevance of faith to fully Encounters with Faith. serve the needs of these athletes. 12.30 Lunch (provided) Chaplaincy in sport has significantly increased over the last 10 years, mainly under the auspices of Sports Chaplaincy UK, which this year is celebrating its 25th 1.30 Brian Hemmings The Sport Psychologist and Chaplain: Reflections on four anniversary. Sports chaplains offer pastoral and spiritual support to all at a club, and & David Chawner: years of collaboration in professional cricket there is clear overlap with sport psychologists in both the role and skillsets. -

Newsletter June 2018

Development funds for growing Christian work Newsletter June 2018 Genesis helps growing churches and Christian Organisations with strategic planning and seed capital in order to multiply their work and implement projects that become self-funding. The project needs to be strategic and have a multiplier effect. We review the development plan, strategies, budgets and management requirements. The grant usually is a reducing commitment over 3 years as the organisation steps to a new level of sustainability. Chairman’s letter The Genesis Foundations have supported 149 projects during 2017/18 to date (156 in 2016/17), including 48 (54) that were approved this year. Of the funds distributed in 2016/17, 26% were directed to youth ministries, 19% to points of influence (Christian media), 18% to Church Development, and 14% to resource ministries. 84% were for Australian projects (overseas projects included 6 with global impact, 4 in Asia, 4 in NZ, 5 in Africa, 1 in UK). Our heavenly Father is reaching out to people all over the world: His message of love, forgiveness and holiness is getting clearer - individuals are accepting Jesus, experiencing the “abundant life” He intended and settling into and growing in churches. We sincerely thank those donors who have continued to support Genesis. I thank our Board and Committee members who volunteer their time. A special thank you to Tara Carr, our Manager Grants and Lisa Wong, our Administrator who have been a great help in the smooth operations of the Foundations. David R Smith Chairman Contents: - Examples -

An Exploration of the Role and Training Needs of Hockey Chaplains

AN EXPLORATION OF THE ROLE AND TRAINING NEEDS OF HOCKEY CHAPLAINS BRUCE HILYARD SMITH B.A., University of New Brunswick, 2002 M.A., Reformed Theological Seminary, 2011 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry Acadia Divinity College, Acadia University Spring Convocation 2016 © by BRUCE HILYARD SMITH, 2016 I, Bruce Hilyard Smith, hereby grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to provide copies of my thesis, upon request, on a non-profit basis. Bruce Hilyard Smith Author Dr. Carol Anne Janzen Supervisor 1 April 2016 Date ii This thesis by Bruce Hilyard Smith was defended successfully in an oral examination on 1 April 2016. The examining committee for the thesis was: Dr. Robert Wilson, Chair F. Christopher Coffin, DMin, External Examiner Dr. Allison Trites, Internal Examiner Dr. Carol Anne Janzen, Supervisor Dr. John McNally, DMin Program Director This thesis is accepted in its present form by Acadia Divinity College, the Faculty of Theology of Acadia University, as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry iii Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................v Abstract ............................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1 -

Sport, Spirituality, and Religion New Intersections

Sport, Spirituality, and Religion New Intersections Edited by Tracy J. Trothen Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Sport, Spirituality, and Religion Sport, Spirituality, and Religion: New Intersections Special Issue Editor Tracy J. Trothen MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Tracy J. Trothen The School of Religion and The School of Rehabilitation Therapy, Queen’s University Canada Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) in 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/ religion sport). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-830-1 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-831-8 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Brett Potter. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Tracy J. Trothen Sport, Spirituality, and Religion: New Intersections Reprinted from: Religions 2019, 10, 545, doi:10.3390/rel10100545 .................. -

Villanova Basketball

VILLANOVA BASKETBALL NovaBasketball @NovaMBB #GoNova @NovaMBB Nova_Nation 2018-19 SCHEDULE & RESULTS GAME 35 | HARTFORD, CT. | XL CENTER DATE OPPONENT TV TIME/RESULTS Nov. 6 Morgan State FS1 W 100-77 NO. 6 VILLANOVA WILDCATS (25-9, 13-5 BIG EAST) Nov. 10 Quinnipiac (WFC) FS2 W 86-53 Head Coach: Jay Wright Nov. 14 Michigan FS1 L 73-46 Record at VU: 447-174 Nov. 17 Furman FS2 L 76-68 OT ADVOCARE INVITATIONAL MARCH 21, 2019 | 7:20 P.M. | TV: TBS Announcers: Carter Blackburn, Deb Antonelli, John Schriffen Nov. 22 vs. Canisius ESPN2 W 82-56 Radio: 610 ESPN - Play-By-Play: Ryan Fannon Analyst: Whitey Rigsby Nov. 23 vs. Oklahoma State ESPN W 77-58 Nov. 25 vs. Florida State ESPN W 66-60 IT’S WORTH NOTING... Dec. 1 at La Salle + ESPN2 W 85-78 ~A 74-72 victory over Seton Hall before straight seasons. It is the 15th time that a sellout crowd of 19,812 last Satur- the Wildcats have posted 25 or more Dec. 5 Temple + FS1 W 69-59 day gave Villanova its fifth BIG EAST wins in a season. Dec. 8 Saint Joseph’s + FS1 W 70-58 Tournament title in program history, fourth in the past five seasons, and third ~ Unanimous first team All-BIG EAST Dec. 11 at Penn + ESPN2 L 78-75 straight. The Wildcats are the first team selection Eric Paschall was also named Dec. 15 at Kansas ESPN L 74-71 in BIG EAST history to win the post- to the BIG EAST All-Tournament team season tournament in three consecutive after scoring 17 points and collecting Dec. -

Pastors Face a Perfect Storm by Frank Brown

from the dean Dear Alumni and Friends of Yale Divinity School, As the cover of this issue of Spectrum indicates, the Yale significant gift to the cam- Divinity School community welcomed back into service in paign came from Robert August of 2009 the “back buildings” on the eastern end of McNeil, Yale College ’36, the Quad. They have been “mothballed” since the recon- to endow the deanship in struction of the Quad at the beginning of this decade. On the honor of his grandfather, southeast side, the space that had housed the old basketball Henry L. Slack, YDS 1877. court and was later converted to the ISM’s Great Hall now Such wonderful generos- has lovely new o∞ces for the Center for Faith & Culture; an ity is a sign of hope for the o∞ce for the Tony Blair Faith Foundation (which, as you successful completion of may know, is in partnership with Yale University to explore the campaign. issues of faith and globalization); space for visiting faculty; and much-needed new instructional space. On the northeast One of the things that will side, the old Common Room and Refectory have been par- change in our e≠orts to tially restored for temporary use by the School of Music as streamline operations is early as next summer. In the meantime, we have been using our annual communication those old familiar spaces for special events, while we hope with alums. We shall increasingly rely on electronic distribu- for their final restoration to our physical plant, perhaps in tion of our information and are planning to move Spectrum connection with new student accommodations to replace the online for the future. -

SCOTT COUNTY VIRGINIA SCHOOLS Phone: 276-386-6118 Fax: 276-386-2684

SCOTT COUNTY VIRGINIA SCHOOLS Phone: 276-386-6118 Fax: 276-386-2684 http://scott.kl2.va.us Board Meeting Agenda (Regular Meeting) Date: June 7,2016 (Tuesday) Time:6:30 p.m Location: Scott County School Board Office 340 East Jackson Street, Gate CitV,VA2425t 1. CallTo Order at 6:30 p.m. 2. Moment of Silence/P/edge of Allegiance 3. ltems to Add to Agenda/Approval of Agenda 4. Approval of Minutes: May 3, 2016 Regular Board Meeting May t7 ,2016 Special Board Meeting 5. Approval of Claims 6. Presentation from Rye Cove Little League 7. Public Comment 8. Superintendent's Report A. Approval of Signatures in Absence of Superintendent B. Approval of Grant Applications C. Approval of Head Start Self-Assessment Results - Program Year 2015-2016 D. Approvalof Head Start Employee ListforJuly L,2Ot6 -June 30,20t7 E. Approval of Head Start Grant Number 03CH3469/2 COLA F. Approval of Head Start Financial Report for April, 2016 G. Approval of Grade 12 Mathematics Capstone Course for 20L6-20!7 H. Approval of Partnership with Southern Appalachian Mountains Food Buying Co-operative (SAM) and Extension of Current Contract for Food & Supplies L Approval of VPSA Technology Resolution J. Approval of Revised Guidelines for "Out of Season" Athletics K. Nomination of School Board Member for VSBA Advocate for Education Award L. Building Services Update 9. Closed Meeting: Motion to Enter (Specify ltems) 1-0. Motion to Return to Regular Meeting & Certifli Closed Meeting L1. ltems by Supervisor of Personnel/Student Services - Jason Smith A. Overnight Field Trips C. Personnel 12. -

Omer Yurtseven Recorded His Eighth Double-Double with 10 Points and 11 Rebounds

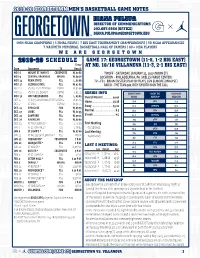

2019-20 GEORGETOWN MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS 202.687.6564 (OFFICE) [email protected] 1984 NCAA CHAMPIONS | 5 FINAL FOURS | 7 BIG EAST TOURNAMENT CHAMPIONSHIPS | 30 NCAA APPEARANCES 7 NAISMITH MEMORIAL BASKETBALL HALL OF FAMERS | 60+ NBA PLAYERS WE ARE GEORGETOWN SCHEDULE GAME 17: GEORGETOWN (11-5, 1-2 BIG EAST) Time/ AT NO. 16/16 VILLANOVA (11-3, 2-1 BIG EAST) Date Opponent TV Result NOV. 6 MOUNT ST. MARY’S CBSSPORTS W, 81-68 TIPOFF – SATURDAY, JANUARY 11, 2020 (NOON ET) NOV. 9 CENTRAL ARKANSAS MASN2 W, 89-78 LOCATION – PHILADELPHIA, PA. (WELLS FARGO CENTER) NOV. 14 PENN STATE ! FS1 L, 81-66 TV – FS1 - BRIAN CUSTER (PLAY-BY-PLAY), LEN ELMORE (ANALYST) NOV. 17 GEORGIA STATE FS1 W, 91-83 RADIO – THE TEAM 980, RICH CHVOTKIN ON THE CALL NOV. 21 VS. NO. 22/22 TEXAS # ESPN2 W, 82-66 NOV. 22 VS. NO. 1/1 DUKE # ESPN2 L, 81-73 SERIES INFO GEORGETOWN ABOUT THE VILLANOVA NOV. 30 UNC GREENSBORO FS2 L, 65-61 Overall Record ............. 44-40 HOYAS MATCHUP WILDCATS DEC. 4 AT RV/25 OKLAHOMA STATE % ESPN+ W, 81-74 Home ............................ 23-16 79.6 PPG 75.1 DEC. 7 AT SMU ESPNU W, 91-74 Away ............................ 15-21 72.2 OPP PPG 67.1 DEC. 14 SYRACUSE FOX W, 89-79 DEC. 17 UMBC FS1 W, 81-55 Neutral ............................. 6-3 45.4 FG% 45.0 DEC. 21 SAMFORD FS1 W, 99-71 Streak ...............................w1 41.7 OPP FG% 43.9 DEC. 28 AMERICAN FS1 W, 80-60 103 3PM 128 DEC.