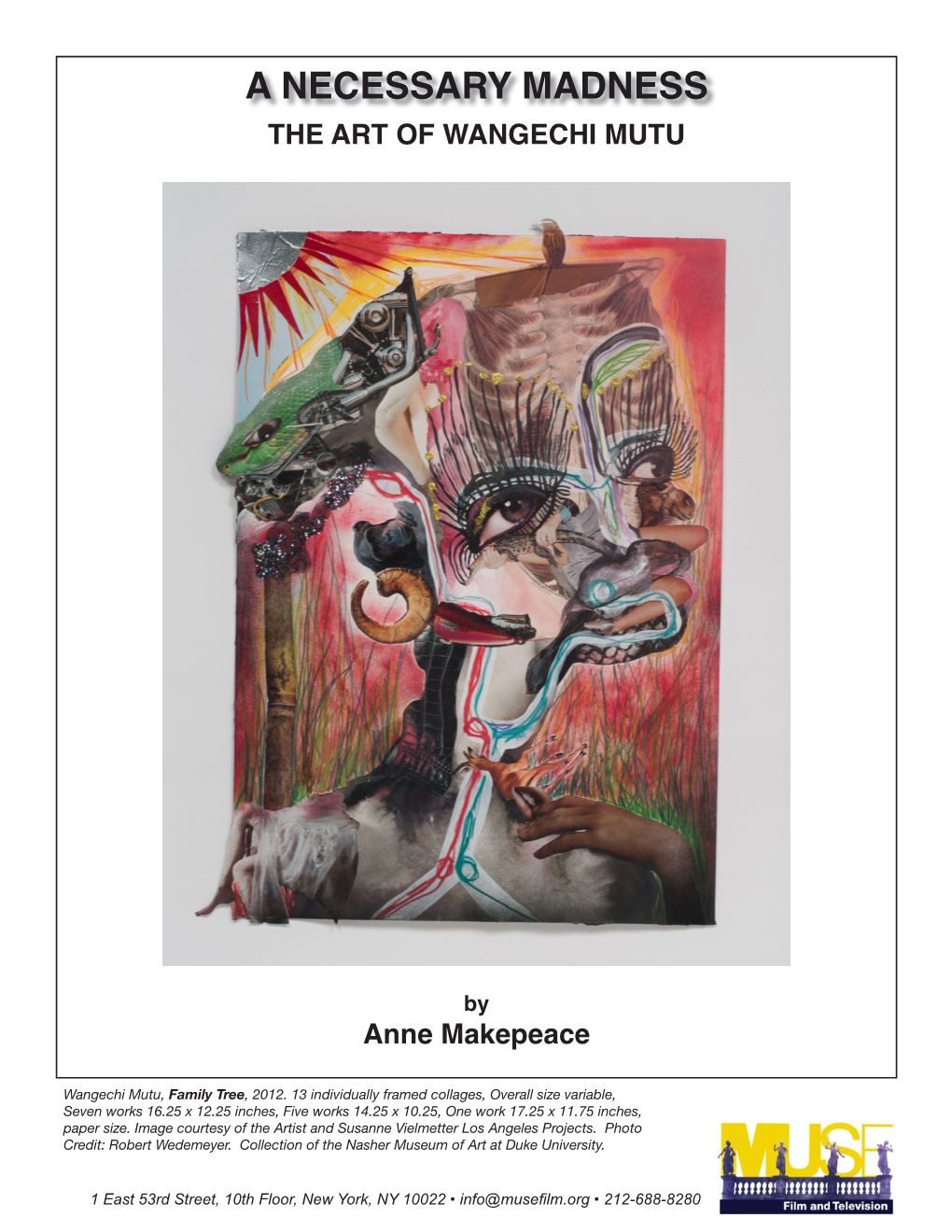

A Necessary Madness the Art of Wangechi Mutu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move

InsightFall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move The newsletter of the University of Delaware Department of Art History Credits Fall 2019 Editor: Kelsey Underwood Design: Kelsey Underwood Visual Resources: Derek Churchill Business Administrator: Linda Magner Insight is produced by the Department of Art History as a service to alumni and friends of the department. Contact Us Sandy Isenstadt, Professor and Chair, Department of Art History Contents E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8105 Derek Churchill, Director, Visual Resources Center E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 From the Chair 4 Commencement 28 Kelsey Underwood, Communications Coordinator From the Editor 5 Graduate Student News 29 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 Around the Department 6 Graduate Student Awards Linda J. Magner, Business Administrator E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8416 Faculty News 11 Graduate Student Notes Lauri Perkins, Administrative Assistant Faculty Notes Alumni Notes 43 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8415 Undergraduate Student News 23 Donors & Friends 50 Please contact us to pose questions or to provide news that may be posted on the department Undergraduate Student Awards How to Donate website, department social media accounts and/ or used in a future issue of Insight. Undergraduate Student Notes Sign up to receive the Department of Art History monthly newsletter via email at ow.ly/ The University of Delaware is an equal opportunity/affirmative action Top image: Old College Hall. (Photo by Kelsey Underwood) TPvg50w3aql. employer and Title IX institution. For the university’s complete non- discrimination statement, please visit www.udel.edu/home/legal- Right image: William Hogarth, “Scholars at a Lecture” (detail), 1736. -

Nathaniel Mary Quinn

NATHANIEL MARY QUINN Press Pack 612 NORTH ALMONT DRIVE, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 TEL 310 550 0050 FAX 310 550 0605 WWW.MBART.COM NATHANIEL MARY QUINN BORN 1977, Chicago, IL Lives and works in Brooklyn, NY EDUCATION 2002 M.F.A. New York University, New York NY 2000 B.A. Wabash College, Crawfordsville, IN SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Madison Museum of Art, Madison, WI (forthcoming) 2018 The Land, Salon 94, New York, NY Soundtrack, M+B, Los Angeles, CA 2017 Nothing’s Funny, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL On that Faithful Day, Half Gallery, New York, NY 2016 St. Marks, Luce Gallery, Torino, Italy Highlights, M+B, Los Angeles, CA 2015 Back and Forth, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL 2014 Past/Present, Pace London Gallery, London, UK Nathaniel Mary Quinn: Species, Bunker 259 Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2013 The MoCADA Windows, Museum of Contemporary and African Diasporan Arts Brooklyn, NY 2011 Glamour and Doom, Synergy Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2008 Deception, Animals, Blood, Pain, Harriet’s Alter Ego Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2007 The Majic Stick, curated by Derrick Adams, Rush Arts Gallery, New York, NY The Boomerang Series, Colored Illustrations/One Person Exhibition: “The Sharing Secret” Children’s Book, The Children’s Museum of the Arts, New York, NY 2006 Urban Portraits/Exalt Fundraiser Benefit, Rush Arts Gallery, New York, NY Couture-Hustle, Steele Life Gallery, Chicago, IL 612 NORTH ALMONT DRIVE, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 TEL 310 550 0050 FAX 310 550 0605 WWW.MBART.COM 2004 The Great Lovely: From the Ghetto to the Sunshine, curated by Hanne -

Kristine Stiles

Concerning Consequences STUDIES IN ART, DESTRUCTION, AND TRAUMA Kristine Stiles The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London KRISTINE STILES is the France Family Professor of Art, Art Flistory, and Visual Studies at Duke University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2016 by Kristine Stiles All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 12345 ISBN13: 9780226774510 (cloth) ISBN13: 9780226774534 (paper) ISBN13: 9780226304403 (ebook) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226304403.001.0001 Library of Congress CataloguinginPublication Data Stiles, Kristine, author. Concerning consequences : studies in art, destruction, and trauma / Kristine Stiles, pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9780226774510 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226774534 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226304403 (ebook) 1. Art, Modern — 20th century. 2. Psychic trauma in art. 3. Violence in art. I. Title. N6490.S767 2016 709.04'075 —dc23 2015025618 © This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper). In conversation with Susan Swenson, Kim Jones explained that the drawing on the cover of this book depicts directional forces in "an Xman, dotman war game." The rectangles represent tanks and fortresses, and the lines are for tank movement, combat, and containment: "They're symbols. They're erased to show movement. 111 draw a tank, or I'll draw an X, and erase it, then redraw it in a different posmon... -

42 Artists Donate Works to Sotheby's Auction Benefitting the Studio Museum in Harlem

42 Artists Donate Works to Sotheby’s Auction Benefitting the Studio Museum in Harlem artnews.com/2018/05/03/42-artists-donate-works-sothebys-auction-benefitting-studio-museum-harlem Grace Halio May 3, 2018 Mark Bradford’s Speak, Birdman (2018) will be auctioned at Sotheby’s in a sale benefitting the Studio Museum in Harlem. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH Sotheby’s has revealed the 42 artists whose works will be on offer at its sale “Creating Space: Artists for The Studio Museum in Harlem: An Auction to Benefit the Museum’s New Building.” Among the pieces at auction will be paintings by Mark Bradford, Julie Mehretu, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Glenn Ligon, and Njideka Akunyili Crosby, all of which will hit the block during Sotheby’s contemporary art evening sale and day sales in New York, on May 16 and 17, respectively. The sale’s proceeds will support the construction of the Studio Museum’s new building on 125th Street, the first space specifically developed to meet the institution’s needs. Designed by David Adjaye, of the firm Adjaye Associates, and Cooper Robertson, the new building will provide both indoor and outdoor exhibition space, an education center geared toward deeper community engagement, a public hall, and a roof terrace. “Artists are at the heart of everything the Studio Museum has done for the past fifty years— from our foundational Artist-in-Residence program to creating impactful exhibitions of artists of African descent at every stage in their careers,” Thelma Golden, the museum’s director and chief curator, said in a statement. -

Art Review “Wangechi Mutu: Solo Exhibition at Brooklyn Museum”

Vol. 16, No. 1 International Journal of Multicultural Education 2014 Art Review “Wangechi Mutu: Solo Exhibition at Brooklyn Museum” Dr. Hwa Young Caruso Art Review Editor From October 2013 until March 2014, the Brooklyn Museum in New York City sponsored a solo exhibition entitled Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey. The 50 artworks filled the feminist art section on the 4th floor of the Museum. These artworks were created by Wangechi Mutu, a female Kenyan artist, between 2002 and 2013. The exhibition was coordinated by Saisha Grayson, Assistant Curator at Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum. Visitors could appreciate mixed-media large-scale collages, sculptures, site-specific wall paintings, installations, and three videos. Small sketchbook drawings in two glass cases provided an unusual opportunity to examine Mutu’s process of developing her ideas and imagination to complete impressive artworks. Wangechi Mutu was born in 1972 in Nairobi, Kenya; attended boarding school in Wales, UK; and moved to New York City in 1992. She graduated from Cooper Union in 1996 and Yale University in 2000 and currently lives and works as an active artist in Brooklyn, NY. Exhibition Highlights At the entrance of her exhibition, two large scale diptychs (59 1/8 x 85 inches) mixed-media paintings welcomed visitors. One painting entitled Yo Mama (2003) is dominated by a pink background with an eroticized African female wearing stiletto high heels and holding a decapitated pink snake with its body connecting dichotomous worlds. Oversized mushrooms and spores are floating in the painting with black palm trees sprouting on one surface. -

On the Basis of Art: 150 Years of Women at Yale Press Release

YA L E UNIVERSITY A R T PRESS For Immediate Release GALLERY RELEASE April 29, 2021 ON THE BASIS OF ART: 150 YEARS OF WOMEN AT YALE Yale University Art Gallery celebrates the work of Yale-educated women artists in a new exhibition from September 2021 through January 2022 April 29, 2021, New Haven, Conn.—On the Basis of Art: 150 Years of Women at Yale celebrates the vital contributions of generations of Yale-trained women artists to the national and interna- tional art scene. Through an exploration of their work, the exhibition charts the history of women at the Yale School of Art (formerly Yale School of the Fine Arts) and traces the ways in which they challenged boundaries of time and cir- cumstance and forged avenues of opportunity—attaining gallery and museum representation, developing relation- ships with dedicated collectors, and securing professorships and teaching posts in a male-dominated art world. On view at the Yale University Art Gallery from September 10, 2021, through January 9, 2022, the exhibition commemorates two recent milestones: the 50th anniversary of coeducation at Yale Irene Weir (B.F.A. 1906), The Blacksmith, College and the 150th anniversary of Yale University’s admit- Chinon, France, ca. 1923. Watercolor on paper. Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Irene Weir, tance of its first female students who, flaunting historical B.F.A. 1906 precedent, were welcomed to study at the School of the Fine Arts upon its opening in 1869. On the Basis of Art showcases more than 75 artists working in a broad range of media, includ- ing painting, sculpture, drawing, print, photography, textile, and video. -

Library Guide 30 Americans

Library Guide 30 Americans Soundsuit by Nick Cave Vignette #10 by Kerry James Marshall Bird On Money by Jean-Michel Basquiat Resource List | 2019 The exhibition 30 Americans is drawn from the Rubell Family Collection and presents American experiences seen through the distinct lens of the African American artists included in the this exhibition. The works on display engage with issues of race, history, identity and beauty that have shaped American life and art over the last four decades. This bibliography highlights select books from the library’s collection that examine the careers of the artists, the exhibition featuring their work, as well as compilations of contemporary African American art. Some of the artists included in this exhibition have few resources available and in these cases articles and artist websites are linked. If you have questions, please contact the reference staff at the Spencer Art Reference Library (telephone: 816.751.1216). Library hours and services are on the Museum’s website at www.nelson-atkins.org Selected by: Roberta Wagener | Library Assistant, Public Services 30 Americans The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. “30 Rubell Family Collection. 30 Americans. 4th Americans.” Accessed February 14, 2019. edition. Miami: Rubell Family Collection, 2017. https://www.nelson-atkins.org/events/30- Call No: N6538 .N5 A15 2017 americans/ Library Resource List 2019 | 30 Americans | 1 Artists Included in the Exhibition Foster, Carter E. Neither New nor Correct: New Nina Chanel Abney Work by Mark Bradford. New York: Whitney Hasting, Julia. Vitamin P2: New Pespectives in Museum of American Art, 2007. Painting. London: Phaidon, 2011. -

Wangechi Mutu

WANGECHI MUTU Born in 1972, Nairobi, Kenya Lives and works in New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2001 Il Capricorno, Venice, Italy 2010 Hunt Bury Flee, Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY My Dirty Little Heaven Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, Germany; traveled to Wiels Contemporary Museum, Brussels, Belgium This you call civilization? Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada 2009 Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, CA 2008 Wangechi Mutu:In Whose Image? Kunsthalle Wien Museum, Project Space Karlsplatz, Curated by Angela Stief, Vienna, Austria Little Touched, Susanne Vielmetter Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2007 YO.N.I, Victoria Miro Gallery, London, UK The Cinderella Curse, ACA Gallery of SCAD, Atlanta, GA Cleanning Earth, Franklin Artworks, Minneapolis, MN 2006 An Alien Eye and Other Killah Anthems, Sikkema Jenkins Co, New York, NY Exhuming Gluttony: A Lover’s Requiem, Salon 94, New York, NY Sleeping Heads Lie, Power House, Memphis, TN 2005 The Chief Lair’s A Holy Mess, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA (Brochure) Wangechi Mutu - Amazing Grace, Miami Art Museum, Miami, FL (Brochure) Problematica, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA 2004 Hangin In Texas, Art Pace, San Antonio, TX WWW.SAATCHIGALLERY.COM WANGECHI MUTU 2003 Pagan Poetry, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA Creatures, Jamaica Center for the Arts and Learning, Queens,NY SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2012 30 Americans, The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington 2011 Stargazers:Elizabeth Catlett in Conversation with 21 Contemporary -

Wangechi Mutu Nguva Na Nyoka

Gallery I, Lower Level Clockwise from entrance Reception Killing you softly, 2014 Mountain of prayer, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl Collage painting on vinyl 201.3 x 147.3 cm 77.5 x 90.2 cm, 30 1/2 x 35 1/2 in 79 1/4 x 58 in Private collection If we live through it, Gallery I, Upper Level She’ll carry us back, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl Long John flapper, 2014 182.9 x 152.4 cm Collage painting on vinyl 72 x 60 in 184.2 x 154.9 cm 72 1/2 x 61 in Even, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl 184.8 x 154.9 cm Nguva, 2013 72 3/4 x 61 in Video (color, sound) 17 minutes, 52 seconds Edition of 6 Beneath lies the Power, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl 212.1 x 156.2 cm Sleeping Serpent, 2014 83 1/2 x 61 1/2 in Mixed media fabric and ceramic 91 x 91 x 945 cm 35 7/8 x 35 7/8 x 372 1/8 in History Trolling, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl 92.1 x 154.9 cm 36 1/4 x 61 in The screamer island dreamer, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl 184.8 x 154.9 cm 72 3/4 x 61 in My mothership, 2014 Collage painting on linoleum 63.5 x 100.3 cm 25 x 39 1/2 in The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue Texts by Adrienne Edwards and Binyavanga Wainaina Wangechi Mutu Nguva na Nyoka 287 (h) x 225 mm, 60pp, Hardback Illustrations: 25 colour and b/w approx. -

Destabilizing the Sign: the Collage Work of Ellen Gallagher, Wangechi Mutu, and Mickalene Thomas”

“Destabilizing the Sign: The Collage Work of Ellen Gallagher, Wangechi Mutu, and Mickalene Thomas” A Thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Masters of Arts in Art History Committee Members: Dr. Kimberly Paice (chair) Dr. Morgan Thomas Dr. Susan Aberth April 2013 by: Kara Swami B.A. May 2011, Bard College ABSTRACT This study focuses on the collage work of three living female artists of the African diaspora: Ellen Gallagher (b. 1965), Wangechi Mutu (b. 1972), and Mickalene Thomas (b. 1971). As artists dealing with themes of race and identity, the collage medium provides a site where Gallagher, Mutu, and Thomas communicate ideas about black visibility and representation in our postmodern society. Key in the study is theorizing the semiotic implications in their work, and how these artists employ cultural signs as indicators of identity that are mutable. Ellen Gallagher builds many of her collages on found magazine pages advertising wigs for black women in particular. She defaces the content of these pages by applying abstracted body parts, such as floating eyes and engorged lips, borrowed from black minstrel imagery. Through a process of abstraction and repetition, Gallagher exposes the arbitrariness of the sign—a theory posed by Ferdinand de Sausurre’s semiotic principles—and thereby destabilizes supposed fixity of racial imagery. Wangechi Mutu juxtaposes fragmented images from media sources to construct hybridized figures that are at once beautiful and grotesque. Mutu’s hybrid figures and juxtaposition of disparate images reveal the versatility of the sign and question essentialism. -

Wangechi Mutu (March 10 A.M.), 2009 a FANTASTIC JOURNEY Gelatin Silver Photograph, N ASHER MUSEUM of ART at 1 19 ⁄2 X 15 In

THE INT ERNATIONAL R EVI EW OF A FRI CAN A MERI CAN A R T TRIPLE Ebony Patterson’s CONSCIOUSNESS: Dancehall Politics Diasporic Art in María Magdalena the American Campos-Pons: Context Portfolio Ivory Coast’s Biennale Debut VOL.24 NO.3A | 2013 REVIEWS LaToya Ruby Frazier Self-Portrait Wangechi Mutu (March 10 a.m.), 2009 A FANTASTIC JOURNEY gelatin silver photograph, N ASHER MUSEUM OF ART AT 1 19 ⁄2 x 15 in. D UKE UNIVERSITY Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum D URHAM, NORTH CAROLINA M ARCH 21–JULY 21, 2013 Play and politics are constantly writhing just beneath the surface in Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey. Though the title brings to mind associations of 1960s and 70s sci- fi, Wangechi Mutu’s Afro-futurist worlds forego phallic space rockets and clunky robots for a darker and deeply feminist terrain. Her collages, sculptures, drawings, and films are populated with powerful female bodies that cross between worlds and span generations. Born in Nairobi, Kenya, Mutu’s educa- tional drive brought her to earn a BFA at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and an MFA in sculpture at Yale University. Though she is best known for her collages, Mutu’s full artistic genealogy is represented in A Fantastic Journey, which is a mid-career survey. Sculptural elements installed throughout the exhibition bind the show together. In particular, felt cloth is used throughout the gallery, as wall coverings and sculptural formations. sites, including the local hospital over the daughter. It was not surprising to learn One of Mutu’s iconic transformative fe- course of its final years. -

University of California Santa Cruz a Secret History Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ A SECRET HISTORY OF AMERICAN RIVER PEOPLE A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS In DIGITAL ART AND NEW MEDIA By Wesley Modes June 2015 The Thesis of Wesley Modes is approved: _______________________________ Professor Jennifer Gonzales _______________________________ Professor Dee Hibbert-Jones _______________________________ Professor Irene Gustafson _______________________________ Professor Chris Connery _______________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Wesley Modes 2015 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................ iv Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... v Dedication ..................................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................