Cyborg Grammar?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

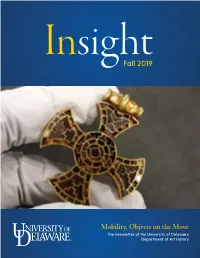

Fall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move

InsightFall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move The newsletter of the University of Delaware Department of Art History Credits Fall 2019 Editor: Kelsey Underwood Design: Kelsey Underwood Visual Resources: Derek Churchill Business Administrator: Linda Magner Insight is produced by the Department of Art History as a service to alumni and friends of the department. Contact Us Sandy Isenstadt, Professor and Chair, Department of Art History Contents E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8105 Derek Churchill, Director, Visual Resources Center E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 From the Chair 4 Commencement 28 Kelsey Underwood, Communications Coordinator From the Editor 5 Graduate Student News 29 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 Around the Department 6 Graduate Student Awards Linda J. Magner, Business Administrator E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8416 Faculty News 11 Graduate Student Notes Lauri Perkins, Administrative Assistant Faculty Notes Alumni Notes 43 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8415 Undergraduate Student News 23 Donors & Friends 50 Please contact us to pose questions or to provide news that may be posted on the department Undergraduate Student Awards How to Donate website, department social media accounts and/ or used in a future issue of Insight. Undergraduate Student Notes Sign up to receive the Department of Art History monthly newsletter via email at ow.ly/ The University of Delaware is an equal opportunity/affirmative action Top image: Old College Hall. (Photo by Kelsey Underwood) TPvg50w3aql. employer and Title IX institution. For the university’s complete non- discrimination statement, please visit www.udel.edu/home/legal- Right image: William Hogarth, “Scholars at a Lecture” (detail), 1736. -

Nathaniel Mary Quinn

NATHANIEL MARY QUINN Press Pack 612 NORTH ALMONT DRIVE, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 TEL 310 550 0050 FAX 310 550 0605 WWW.MBART.COM NATHANIEL MARY QUINN BORN 1977, Chicago, IL Lives and works in Brooklyn, NY EDUCATION 2002 M.F.A. New York University, New York NY 2000 B.A. Wabash College, Crawfordsville, IN SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Madison Museum of Art, Madison, WI (forthcoming) 2018 The Land, Salon 94, New York, NY Soundtrack, M+B, Los Angeles, CA 2017 Nothing’s Funny, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL On that Faithful Day, Half Gallery, New York, NY 2016 St. Marks, Luce Gallery, Torino, Italy Highlights, M+B, Los Angeles, CA 2015 Back and Forth, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL 2014 Past/Present, Pace London Gallery, London, UK Nathaniel Mary Quinn: Species, Bunker 259 Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2013 The MoCADA Windows, Museum of Contemporary and African Diasporan Arts Brooklyn, NY 2011 Glamour and Doom, Synergy Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2008 Deception, Animals, Blood, Pain, Harriet’s Alter Ego Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2007 The Majic Stick, curated by Derrick Adams, Rush Arts Gallery, New York, NY The Boomerang Series, Colored Illustrations/One Person Exhibition: “The Sharing Secret” Children’s Book, The Children’s Museum of the Arts, New York, NY 2006 Urban Portraits/Exalt Fundraiser Benefit, Rush Arts Gallery, New York, NY Couture-Hustle, Steele Life Gallery, Chicago, IL 612 NORTH ALMONT DRIVE, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 TEL 310 550 0050 FAX 310 550 0605 WWW.MBART.COM 2004 The Great Lovely: From the Ghetto to the Sunshine, curated by Hanne -

Kristine Stiles

Concerning Consequences STUDIES IN ART, DESTRUCTION, AND TRAUMA Kristine Stiles The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London KRISTINE STILES is the France Family Professor of Art, Art Flistory, and Visual Studies at Duke University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2016 by Kristine Stiles All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 12345 ISBN13: 9780226774510 (cloth) ISBN13: 9780226774534 (paper) ISBN13: 9780226304403 (ebook) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226304403.001.0001 Library of Congress CataloguinginPublication Data Stiles, Kristine, author. Concerning consequences : studies in art, destruction, and trauma / Kristine Stiles, pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9780226774510 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226774534 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226304403 (ebook) 1. Art, Modern — 20th century. 2. Psychic trauma in art. 3. Violence in art. I. Title. N6490.S767 2016 709.04'075 —dc23 2015025618 © This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper). In conversation with Susan Swenson, Kim Jones explained that the drawing on the cover of this book depicts directional forces in "an Xman, dotman war game." The rectangles represent tanks and fortresses, and the lines are for tank movement, combat, and containment: "They're symbols. They're erased to show movement. 111 draw a tank, or I'll draw an X, and erase it, then redraw it in a different posmon... -

42 Artists Donate Works to Sotheby's Auction Benefitting the Studio Museum in Harlem

42 Artists Donate Works to Sotheby’s Auction Benefitting the Studio Museum in Harlem artnews.com/2018/05/03/42-artists-donate-works-sothebys-auction-benefitting-studio-museum-harlem Grace Halio May 3, 2018 Mark Bradford’s Speak, Birdman (2018) will be auctioned at Sotheby’s in a sale benefitting the Studio Museum in Harlem. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH Sotheby’s has revealed the 42 artists whose works will be on offer at its sale “Creating Space: Artists for The Studio Museum in Harlem: An Auction to Benefit the Museum’s New Building.” Among the pieces at auction will be paintings by Mark Bradford, Julie Mehretu, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Glenn Ligon, and Njideka Akunyili Crosby, all of which will hit the block during Sotheby’s contemporary art evening sale and day sales in New York, on May 16 and 17, respectively. The sale’s proceeds will support the construction of the Studio Museum’s new building on 125th Street, the first space specifically developed to meet the institution’s needs. Designed by David Adjaye, of the firm Adjaye Associates, and Cooper Robertson, the new building will provide both indoor and outdoor exhibition space, an education center geared toward deeper community engagement, a public hall, and a roof terrace. “Artists are at the heart of everything the Studio Museum has done for the past fifty years— from our foundational Artist-in-Residence program to creating impactful exhibitions of artists of African descent at every stage in their careers,” Thelma Golden, the museum’s director and chief curator, said in a statement. -

Art Review “Wangechi Mutu: Solo Exhibition at Brooklyn Museum”

Vol. 16, No. 1 International Journal of Multicultural Education 2014 Art Review “Wangechi Mutu: Solo Exhibition at Brooklyn Museum” Dr. Hwa Young Caruso Art Review Editor From October 2013 until March 2014, the Brooklyn Museum in New York City sponsored a solo exhibition entitled Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey. The 50 artworks filled the feminist art section on the 4th floor of the Museum. These artworks were created by Wangechi Mutu, a female Kenyan artist, between 2002 and 2013. The exhibition was coordinated by Saisha Grayson, Assistant Curator at Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum. Visitors could appreciate mixed-media large-scale collages, sculptures, site-specific wall paintings, installations, and three videos. Small sketchbook drawings in two glass cases provided an unusual opportunity to examine Mutu’s process of developing her ideas and imagination to complete impressive artworks. Wangechi Mutu was born in 1972 in Nairobi, Kenya; attended boarding school in Wales, UK; and moved to New York City in 1992. She graduated from Cooper Union in 1996 and Yale University in 2000 and currently lives and works as an active artist in Brooklyn, NY. Exhibition Highlights At the entrance of her exhibition, two large scale diptychs (59 1/8 x 85 inches) mixed-media paintings welcomed visitors. One painting entitled Yo Mama (2003) is dominated by a pink background with an eroticized African female wearing stiletto high heels and holding a decapitated pink snake with its body connecting dichotomous worlds. Oversized mushrooms and spores are floating in the painting with black palm trees sprouting on one surface. -

On the Basis of Art: 150 Years of Women at Yale Press Release

YA L E UNIVERSITY A R T PRESS For Immediate Release GALLERY RELEASE April 29, 2021 ON THE BASIS OF ART: 150 YEARS OF WOMEN AT YALE Yale University Art Gallery celebrates the work of Yale-educated women artists in a new exhibition from September 2021 through January 2022 April 29, 2021, New Haven, Conn.—On the Basis of Art: 150 Years of Women at Yale celebrates the vital contributions of generations of Yale-trained women artists to the national and interna- tional art scene. Through an exploration of their work, the exhibition charts the history of women at the Yale School of Art (formerly Yale School of the Fine Arts) and traces the ways in which they challenged boundaries of time and cir- cumstance and forged avenues of opportunity—attaining gallery and museum representation, developing relation- ships with dedicated collectors, and securing professorships and teaching posts in a male-dominated art world. On view at the Yale University Art Gallery from September 10, 2021, through January 9, 2022, the exhibition commemorates two recent milestones: the 50th anniversary of coeducation at Yale Irene Weir (B.F.A. 1906), The Blacksmith, College and the 150th anniversary of Yale University’s admit- Chinon, France, ca. 1923. Watercolor on paper. Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Irene Weir, tance of its first female students who, flaunting historical B.F.A. 1906 precedent, were welcomed to study at the School of the Fine Arts upon its opening in 1869. On the Basis of Art showcases more than 75 artists working in a broad range of media, includ- ing painting, sculpture, drawing, print, photography, textile, and video. -

Library Guide 30 Americans

Library Guide 30 Americans Soundsuit by Nick Cave Vignette #10 by Kerry James Marshall Bird On Money by Jean-Michel Basquiat Resource List | 2019 The exhibition 30 Americans is drawn from the Rubell Family Collection and presents American experiences seen through the distinct lens of the African American artists included in the this exhibition. The works on display engage with issues of race, history, identity and beauty that have shaped American life and art over the last four decades. This bibliography highlights select books from the library’s collection that examine the careers of the artists, the exhibition featuring their work, as well as compilations of contemporary African American art. Some of the artists included in this exhibition have few resources available and in these cases articles and artist websites are linked. If you have questions, please contact the reference staff at the Spencer Art Reference Library (telephone: 816.751.1216). Library hours and services are on the Museum’s website at www.nelson-atkins.org Selected by: Roberta Wagener | Library Assistant, Public Services 30 Americans The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. “30 Rubell Family Collection. 30 Americans. 4th Americans.” Accessed February 14, 2019. edition. Miami: Rubell Family Collection, 2017. https://www.nelson-atkins.org/events/30- Call No: N6538 .N5 A15 2017 americans/ Library Resource List 2019 | 30 Americans | 1 Artists Included in the Exhibition Foster, Carter E. Neither New nor Correct: New Nina Chanel Abney Work by Mark Bradford. New York: Whitney Hasting, Julia. Vitamin P2: New Pespectives in Museum of American Art, 2007. Painting. London: Phaidon, 2011. -

Wangechi Mutu

WANGECHI MUTU Born in 1972, Nairobi, Kenya Lives and works in New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2001 Il Capricorno, Venice, Italy 2010 Hunt Bury Flee, Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY My Dirty Little Heaven Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, Germany; traveled to Wiels Contemporary Museum, Brussels, Belgium This you call civilization? Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada 2009 Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, CA 2008 Wangechi Mutu:In Whose Image? Kunsthalle Wien Museum, Project Space Karlsplatz, Curated by Angela Stief, Vienna, Austria Little Touched, Susanne Vielmetter Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2007 YO.N.I, Victoria Miro Gallery, London, UK The Cinderella Curse, ACA Gallery of SCAD, Atlanta, GA Cleanning Earth, Franklin Artworks, Minneapolis, MN 2006 An Alien Eye and Other Killah Anthems, Sikkema Jenkins Co, New York, NY Exhuming Gluttony: A Lover’s Requiem, Salon 94, New York, NY Sleeping Heads Lie, Power House, Memphis, TN 2005 The Chief Lair’s A Holy Mess, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA (Brochure) Wangechi Mutu - Amazing Grace, Miami Art Museum, Miami, FL (Brochure) Problematica, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA 2004 Hangin In Texas, Art Pace, San Antonio, TX WWW.SAATCHIGALLERY.COM WANGECHI MUTU 2003 Pagan Poetry, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA Creatures, Jamaica Center for the Arts and Learning, Queens,NY SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2012 30 Americans, The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington 2011 Stargazers:Elizabeth Catlett in Conversation with 21 Contemporary -

The Human Machine

EXPLORING THE INCREASINGLY BLURRED LINES BETWEEN HUMANS AND TECHNOLOGY COMPILED BY HOWIE BAUM Almost everyone in the OUR TECHNOLOGY IS AN EXTENSION OF OUR world has a life, dependent HUMANITY on technology. More than a billion people right now are already dependent on assistive technologies like: ❖ Hearing aids ❖ Pacemakers ❖ Prosthetic limbs ❖ Wheelchairs. 1/3 of the world’s population will be wearing glasses or contact lenses by the end of this decade. TYPES OF HUMAN AUGMENTATION The types of Human Augmentation in order of importance can be divided into 2 categories: MOST IMPORTANT: PHYSICAL AND COGNITIVE (THINKING) LEAST IMPORTANT: PERSONALITY AND COSMETIC SIMILAR WORDS ABOUT THE HUMAN MACHINE BIONIC HUMAN TRANSHUMAN AUGMENTED HUMAN CYBORG EYEBORG CYBERNETICS ENHANCED HUMANS HUMAN AUGMENTICS Transhumanism’ is an ‘intellectual and cultural movement’ that promotes the use of technology in order to advance the human condition. What this essentially means, is that a transhumanist is someone who believes we should use technology in order to give ourselves: ▪ Enhanced abilities ▪ Higher IQ’s ▪ Greater strength ▪ Longer lifespans ▪ Sharper senses, etc. Bionic leg components: (a) the artificial hip, (b) artificial knee, and (c) “blade runner” prostheses made with carbon fiber “blades”. A MAJORITY OF PEOPLE IN THE WORLD ARE DEPENDENT ON TECHNOLOGY ❖ Hearing aids ❖ Glasses ❖ Medications ❖ Prosthetics ❖ Smartphones ❖ Contraceptives ❖ Wheelchairs Human existence is a cycle of inventing things to shape life, and in turn, be shaped. There is no “natural” state for humans, not since we mastered fire. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xBiOQKonkWs 4.5 minutes The term “Cyborg” was coined in 1960 by scientists Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline as part of discussions during the Space Race. -

Wangechi Mutu Nguva Na Nyoka

Gallery I, Lower Level Clockwise from entrance Reception Killing you softly, 2014 Mountain of prayer, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl Collage painting on vinyl 201.3 x 147.3 cm 77.5 x 90.2 cm, 30 1/2 x 35 1/2 in 79 1/4 x 58 in Private collection If we live through it, Gallery I, Upper Level She’ll carry us back, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl Long John flapper, 2014 182.9 x 152.4 cm Collage painting on vinyl 72 x 60 in 184.2 x 154.9 cm 72 1/2 x 61 in Even, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl 184.8 x 154.9 cm Nguva, 2013 72 3/4 x 61 in Video (color, sound) 17 minutes, 52 seconds Edition of 6 Beneath lies the Power, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl 212.1 x 156.2 cm Sleeping Serpent, 2014 83 1/2 x 61 1/2 in Mixed media fabric and ceramic 91 x 91 x 945 cm 35 7/8 x 35 7/8 x 372 1/8 in History Trolling, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl 92.1 x 154.9 cm 36 1/4 x 61 in The screamer island dreamer, 2014 Collage painting on vinyl 184.8 x 154.9 cm 72 3/4 x 61 in My mothership, 2014 Collage painting on linoleum 63.5 x 100.3 cm 25 x 39 1/2 in The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue Texts by Adrienne Edwards and Binyavanga Wainaina Wangechi Mutu Nguva na Nyoka 287 (h) x 225 mm, 60pp, Hardback Illustrations: 25 colour and b/w approx. -

Cyborg Art: an Explorative and Critical Inquiry Into Corporeal Human-Technology Convergence

http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Cyborg Art: An Explorative and Critical Inquiry into Corporeal Human-Technology Convergence A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Waikato, by Elizabeth Margaretha Borst Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Elizabeth M. Borst, 2009 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced without permission of the author. University of Waikato, 2009 i ii Abstract This thesis introduces and examines the undervalued concept of corporeal human- technology interface art, or ‘cyborg art’, which describes literal, figural and metaphorical representations of increasing body and technology integration. The transforming (post)human being is therefore the focus; who we are today, and who or what we may become as humanity increasingly interfaces with technology. Theoretical analysis of cyborg imagery centres on the science fiction domain, in particular film and television, as opposed to art.