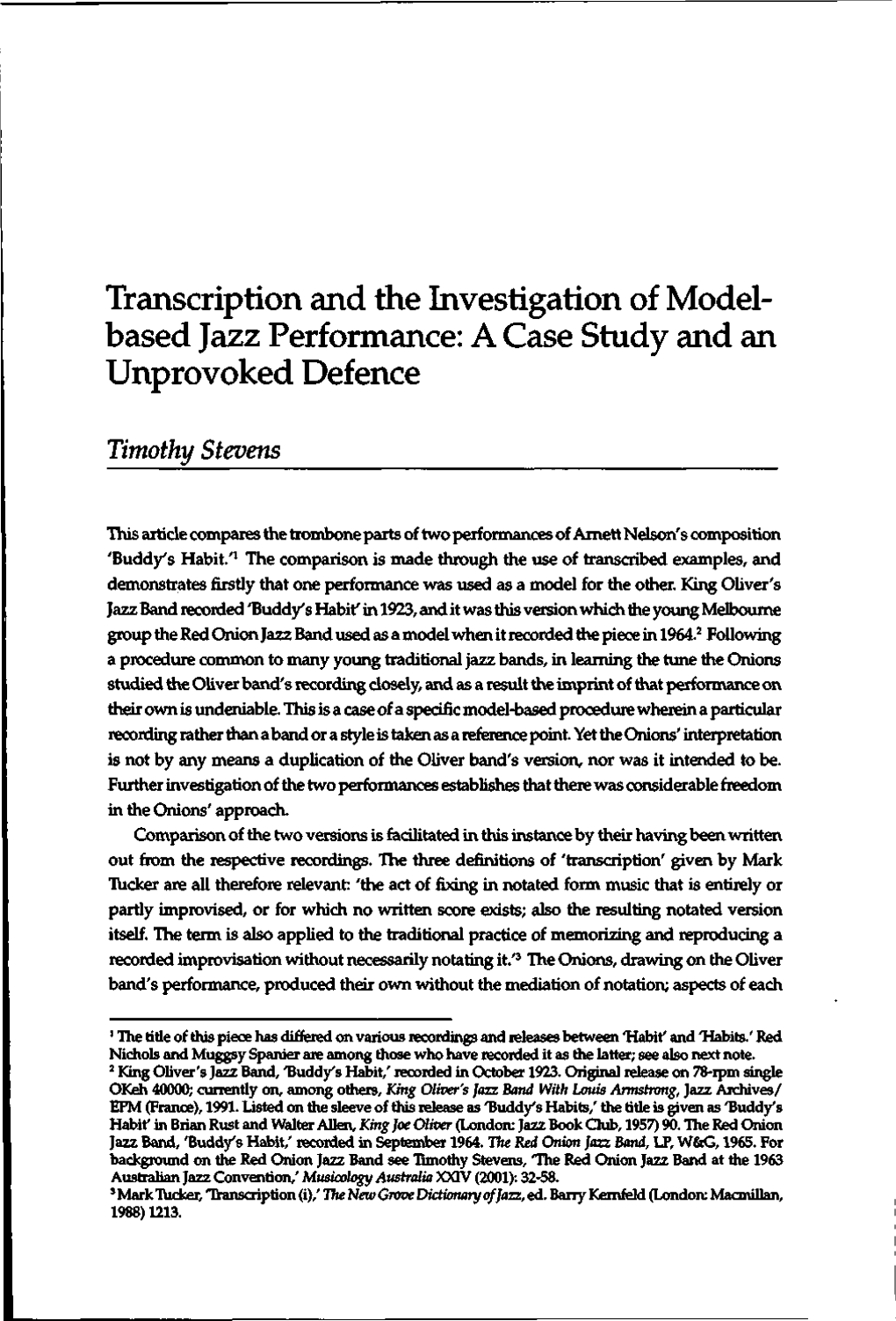

Transcription and the Investigation of Model- Based Jazz Performance: a Case Study and an Unprovoked Defence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

Allan Browne & Richard Miller

ALLAN BROWNE & RICHARD MILLER: MODERNISTS & TRADITIONALISTS Interviewed by Adrian Jackson* __________________________________________________________ [This article appeared in the Winter/Spring 1986 edition of Jazz Magazine.] rummer Allan Browne and saxophonist-clarinettist Richard Miller have been making music together for more than 20 years now. Their partnership began D in 1965 when Miller joined the Red Onion Jazz Band, led by Browne and still remembered as the most successful Australian jazz band of its time. None of their records is currently available, but a cassette (Anteater 002) which contains excerpts from some of the band’s early EPs, plus a recording from a concert in Warsaw in 1967, shows that the band’s reputation was founded on real musical qualities. Many of those qualities were re-captured when the band staged a couple of sell-out reunions at the Limerick Arms Hotel in 1984. The members of the quartet Onaje, L-R, Gary Costello, Bob Sedergreen, Richard Miller, Allan Browne… Since mid-1985, the pair have also displayed their mastery of traditional jazz in the Allan Browne Jazz Band, which plays every Thursday night at the Emerald Hotel in South Melbourne. The other members of that band are trumpeter Peter Gaudion, __________________________________________________________ *In 1986 when this was published, Adrian Jackson was a freelance writer, who had been jazz critic with the Melbourne Age since 1978. 1 Richard Miller (left) and Allan Browne, outside the Limerick Arms Hotel… PHOTO COURTESY AUSTRALIAN JAZZ MUSEUM trombonjst Bill Howard, clarinettist Fred Parkes, bassist Leon Heale and guitarist- banjoist John Scurry; Browne’s wife, Margie, occasionally adds vocals or piano. -

7. a Pdf-Book About Johnny Dodds

BY<3. E. LAMBERT 780.92 D6422L 66-08387 Lambert Johnny Dodds KINGS OF JAZZ Johnny Dodds BY G. E. LAMBERT A Perpetua Book A. 5. BARNES AND COMPANY, INC. NEW YORK <) CasseU & Co. Ltd. 1961 PERPETUA EDITION 1961 Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS PART PAGE 1 HIS LIFE 1 2 HIS RECORDINGS 18 3 HIS CONTRIBUTION TO JAZZ 65 SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY 79 6608387 HIS LIFE In the years when New Orleans was the premier centre of jazz that is from around 1900 to the closing of the Story- ville red light district in 1918 it was a city flooded with music. Every possible occasion picnics, advertising, trips on the Mississippi was provided with music; every place of diversion the bars, theatres, brothels and gambling joints had its musicians. Parades by the various organi- zations had their brass bands, which also played for the unique New Orleans funerals, and dance orchestras of all types were to be heard within the city limits. In the Creole and Negro districts there was scarcely a family who did not boast of several part-time musicians, and there were hundreds of skilled local professionals playing in the various parade bands, jazz bands, society bands and riverboat orchestras. To judge from the material collected by later historians, the doings of the favourite musicians of the city were looked upon with the same interest which 1 the mass of people today accord to sporting heroes and popular cinema or television personalities. There were trumpet players known for their vivacious playing and stamina on the long parades, and others who specialized in the dirges played on the way to and at the graveside; one trumpet player will be remembered for his volume and exuberance in the lower-class dance-halls, another for his unique ability and power of expression on the blues. -

![Istreets] Rampart Street; Then He Went Back to New Orleans University](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4790/istreets-rampart-street-then-he-went-back-to-new-orleans-university-1724790.webp)

Istreets] Rampart Street; Then He Went Back to New Orleans University

PRESTON JACKSON Also present: William Russell I [of 2]-Digest-Retyped June 2, 1958 Preston Jackson was born in the Carrollton section of New Orleans on January 3, 1904 at Cherokee and Ann [now Garfield] Istreets] (according to his mother). He went to "pay" school, then to Thorny Lafon [elementary] School, then to New Orleans University (WR says Bunk Johnson went there years before), which was at Valmont and St. Charles. His family are Methodist and Catholic. PJ moved to the Garden District; he attended McDonogh 25 School, on [South] Rampart Street; then he went back to New Orleans University [High s ]t School Division?] . In about 1920 or 1921, PJ told Joe Oliver he was thinking of taking up trombone; Oliver advised him to take clarinet instead, as PJ was a good whistler and should have an instrument more maneuver- able than the tromboneo Having decided on clarinet, PJ was surprised by his mother, wlio secretly bought him a trombone (August, 1920 or 1921) - PJ found but later that William Robertson, his first teacher, and a trombonist, had bought the horn for PJ's mother (Robertson was from Chicago) . PJ studied with Robertson for about six months; when he had had the horn for about nine months, he was good enough to be invited to play in the band at [Quinn's?] Chapel, where he remained four or five months, playing in the church band. Then PJ met some New Orleans friends and acquaintances/ including Al and Omer Simeon (from the "French part of town"), Bernie Young and 1 PRESTON JACKSON 2 I [of 2]-Digest--Retyped June 2. -

Classical Studies. He Played In\^ Fraternity Band at College. He

WILLIAM RUSSELL also ptesent; August 31, 1962 Reel I-Digest-Retype William R. Hogan 1L Paul R. Crawford First Proofreading: Alma D. Williams William Russell was born February 26, 1905, in Canton, Missouri, on the Mississippi River. His first impressive musical experiences were hearing tlie calliopes on the excursion and show boats which ^ came to and by Canton. He first wanted to play bass drum when lie heard the orchestra in his Sunday School, but he began playing violin when he was ten. His real name is Russell William Wagner. In about 1929 Tne began writing music; Henry Cowell published some of his music in 1933 and WR decided the use of the name Wagner 6n music would be about equal to writing a play and signing it Henry [or Jack or Frank, etc,] Shalcespeare, so he changed his name for that professional reason. His parents are of German ancestry. His father had a zither, which WR and a brother used for playing at .r concerts a la Chautauqua. He remembers hearing Negro bands on the boats playing good jazz as early as 1917 or 1915, and he was fascinated by it, although he felt jazz might contaminate his classical studies. He played in\^ fraternity band at college. He y studied chemistry at college although his main interest was music, He went to Chicago to continue studying music in 1924, and he says 1^e didn't have sense enough to go to the places where King Oliver/ the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, and others were playing then, and he has since regretted that. -

AUGUST 1984 LH: I Wanted to Sit In, If Conway Would Let Me

VOL. 8, NO. 8 Cover Photo by Robert Herman FEATURES LEVON HELM During the late '60s and early '70s, Bob Dylan and The Band were musically a winning combination, due in part to the drumming and singing talents of Levon Helm. The Band went on to record many classics until their breakup in 1976. Here, Levon discusses his background, his work with Dylan and The Band, and the various projects he has been involved with during the past few years. by Robyn Flans 8 THOMMY PRICE Price, one of the hottest new drummers on the scene today, is cur- rently the power behind Billy Idol. Before joining Idol, Thommy Carneau had a five-year gig with Mink DeVille, followed by a year with Fred Scandal. In this interview, Thommy reveals the responsibilities of by working with a top act, his experiences with music video, and how Photo the rock 'n' roll life-style is not all glamour. by Connie Fisher 14 BOB MOSES Bob Moses is truly an original personality in the music world. Although he is known primarily in the jazz idiom for his masterful drumming, he is also an active composer and artist. He talks about his influences, his technique, and the philosophies behind his Jachles various forms of self-expression. by Chip Stern 18 Michael by DRUMMING IN ATLANTIC CITY Photo by Rick Van Horn 22 Malkin WILL DOWER Rick Australian Sessionman by by Rick Van Horn 24 Photo CLUB SCENE ON THE MOVE COLUMNS Attention To Detail James D. Miller and Bob Pignatiello. 78 by Rick Van Horn 90 IN THE STUDIO EDUCATION DRUM SOLOIST Jim Plank CONCEPTS Philly Joe Jones: "Lazy Bird" by Ted Dyer 84 Drummers And Put-Downs by Dan Tomlinson 96 by Roy Burns 28 REVIEWS EQUIPMENT LISTENER'S GUIDE ON TRACK 46 by Peter Erskine and Denny Carmassi 30 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP NEWS ROCK PERSPECTIVES Remo PTS Update Beat Study #13 by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. -

The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band Gene H

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Faculty Publications Music Fall 1994 The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band Gene H. Anderson University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/music-faculty-publications Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Gene H. "The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band." American Music 12, no. 3 (Fall 1994): 283-303. doi:10.2307/ 3052275. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENE ANDERSON The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band On Thursday, April 5, 1923, the Creole Jazz Band stopped off in Rich- mond, Indiana, to make jazz history. The group included Joe Oliver and Louis Armstrong (comets), Johnny Dodds (clarinet), Honor4 Dutrey (trombone), Bill Johnson (banjo), Lil Hardin (piano), and Warren"Baby" Dodds (drums) (fig. 1). For the rest of that day and part of the next, the band cut nine portentous sides, in sessions periodically interrupted by the passage of trains running on tracks near the Gennett studios where the recording took place. By year's end, sessions at OKeh and Columbia Records expanded the number of sides the band made to thirty-nine, creating the first recordings of substance by an African American band--the most significant corpus of early recorded jazz - surpassing those of such white predecessors as the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and the New Orleans Rhythm Kings. -

William Russell: Jazz Lover, Collector, and Musicologist an Annotated Bibliography

William Russell: Jazz Lover, Collector, Musicologist An Annotated Bibliography Ben Wagner Born Russell William Wagner in 1905, William (Bill) Russell was a violinist; an avant-garde composer deeply interested in percussion; accompanist to a touring puppet troupe; a meticulous musical-instrument repairman; a jazz-record producer; an archivist; a writer; and, above all, a New Orleans jazz collector of extraordinary breadth. More than anything else, he simply loved classic New Orleans–style jazz, which he called the “best music I’d ever heard.”1 He sought out obscure, old-time jazz players and was instrumental in the revival of the career of Bunk Johnson. Russell privately showed many kindnesses to jazz musicians down on their luck, encouraging their careers. In an age of segregation, Russell had many close associations with African Americans, organizing recording sessions in houses and rented halls because blacks were not allowed in New Orleans recording studios, nor could they play openly with white musicians. He did much to document and advocate New Orleans as the true birthplace of jazz. Although there were some inaccuracies in his early writings—and the debate continues about the many-faceted origins of American jazz—Russell’s overall analysis has stood up well against later scholarship. He certainly was one of the first to note the importance of place in the development of jazz. From the early 1930s to the end of his life, Russell acquired and documented anything he could find related to jazz: oral-history recordings and transcripts, jam-session recordings, musical instruments, photographs, programs, postcards, ads, city guidebooks, correspondence, sheet music, magazines. -

Chronological Discography

Chronological Discography arranger g guitar as alto saxophone 0 pipe organ bb brass bass (sousaphone/tuba) p piano bj banjo ss soprano saxophone bs baritone saxophone t trumpet c comet tb trombone cl clarinet ts tenor saxophone d drums v vocals db double bass vib vibraphone dir director vn violin f flute This chronological list contains most known releases on which Danny Barker plays and sings. Titles are given as they appear on the record labels. Where possible, the first issue number is given, but the complexity of subsequent reissues is such that these are not shown. In preparing the list much use has been made of the works cited in the acknowledgment section as well as Stagg and Crump: New Orleans: the Revival (Dublin, 1973). 1931 Ward Pinkett (t, v); Albert Nicholas (cO; Jack Russin (p); Danny ]une9 NewYork Barker(g);Joe Watts (db); Sam Weiss (d) Dave's Harlem Highlights 95337-1 Everything is okey-dokey (WP:v) Bluebird B-6144 Dave Nelson (1, v); Clarence Brereton (t); Melvin Herbert/Harry 95338-1 I'm on a see-saw (WP:v) Bluebird B-6130 Brown (t); Wilbur de Paris (tb); Buster Bailey (cl, as); Glyn Paque (cl, 95339-1 Red sails in the sunset (WP:v) Bluebird B-6131 as); Charles Frazier (ts); Wtryman Caroer (ts, f); Sam Allen (p); 95340-1 Tender is the night (WP:v) Bluebird B-6131 •Danny Barker (bj); Simon Marrero (bb); Gerald Hobson (iii 95341-1 I'mpaintingthetownred 69905-1 Somebody stole my gal Timely Tunes C-1587 (to hide a heart that's blue) Bluebird B-6130 69906-1 Rockin' Chair Timely Tunes C-1576 95342-1 Tap Room Special (Panama) Bluebird B-6193 69907-2 Loveless Love Timely Tunes C-1577 69908-2 St. -

Black Bottom Stomp”--Jelly Roll Morton’S Red Hot Peppers (1926) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by Burton W

“Black Bottom Stomp”--Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers (1926) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by Burton W. Peretti (guest post)* Jelly Roll Morton Few recording projects have had as great an impact on the evolution of jazz as this set committed to disk in 1926-1927 by Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers for Victor Records. “Black Bottom Stomp,” especially, emerged from these sessions to define “hot jazz” for younger musicians, such as Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke, and inspired critics and fans alike in future decades to designate Morton’s music as a wellspring of “mainstream” jazz. Almost a century after the recording was made, listeners are still amazed at how much artistry Morton, the composer and bandleader, was able to pack into three minutes of playing. The first eight bars are a vibrant introduction. Kid Ory’s slide trombone gives us an initial taste of the Delta blues that gave New Orleans jazz its sensuous flavor. (Ory, like Morton and the rest of the band, hailed from the Louisiana city.) A busy syncopated figure from clarinetist Omer Simeon and trumpeter George Mitchell evokes ragtime, the show music that reigned for a quarter century before jazz’s emergence. Then we hear the theme, built over three simple chords: four blues flourishes, nearly identical to Ory’s lick but broader and melodic, followed by an emphatic ragtime syncopation from the entire band. These eight bars are repeated. Almost the entire remainder of the number is made up of variations of the theme, built on the same chords. -

Studfield Wantirna Community News

Studeld-Wantirna Community News Edition 10 - Spring 2010 Photo by Elaine Craig of Knox Photographic Society Welcome to a bumper spring edition! ● March 2010 Hail Storm, Knox SES ● The Red Onion Jazz Band ● Wantirna Drive-in ● Focus on Diabetes ● Studeld’s 2nd Winter Festival FREE For quite some time now, I have been campaigning to have a right turning arrow installed at the intersection of Coleman and Stud Roads. Many residents and local business owners have asked me to ght on - that it’s only a matter of time before someone is seriously injured or killed. There have been many near misses and I’ve always been a subscriber to the old saying ‘prevention is better than cure’. So that’s why I’m asking for your help. A petition to the Victorian parliament is currently available for you to sign at many Studeld retailers and at my ofce. If you can’t make it to one of these places, I’d be happy to pop a petition sheet in the mail to you. Simply call my ofce on 9729 1622 or email me, and we’ll get it to you. Thanks, in advance, for all your support for this important change to our area. My ofce is located at: 2/40 Station St, Bayswater, VIC 3153. Ph: 03 9729 1622 Fax : 03 9729 0912 Email: [email protected] Refinancing your home won’t make that much Say ‘Hello’ difference right? Wrong!! When you know what to look for there are more differences and savings that you can poke a mortgage broker at. -

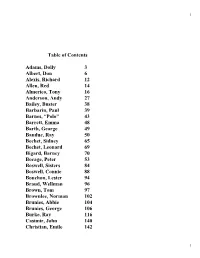

Collection of Jazz Articles

1 Table of Contents Adams, Dolly 3 Albert, Don 6 Alexis, Richard 12 Allen, Red 14 Almerico, Tony 16 Anderson, Andy 27 Bailey, Buster 38 Barbarin, Paul 39 Barnes, “Polo” 43 Barrett, Emma 48 Barth, George 49 Bauduc, Ray 50 Bechet, Sidney 65 Bechet, Leonard 69 Bigard, Barney 70 Bocage, Peter 53 Boswell, Sisters 84 Boswell, Connie 88 Bouchon, Lester 94 Braud, Wellman 96 Brown, Tom 97 Brownlee, Norman 102 Brunies, Abbie 104 Brunies, George 106 Burke, Ray 116 Casimir, John 140 Christian, Emile 142 1 2 Christian, Frank 144 Clark, Red 145 Collins, Lee 146 Charles, Hypolite 148 Cordilla, Charles 155 Cottrell, Louis 160 Cuny, Frank 162 Davis, Peter 164 DeKemel, Sam 168 DeDroit, Paul 171 DeDroit, John 176 Dejan, Harold 183 Dodds, “Baby” 215 Desvigne, Sidney 218 Dutrey, Sam 220 Edwards, Eddie 230 Foster, “Chinee” 233 Foster, “Papa” 234 Four New Orleans Clarinets 237 Arodin, Sidney 239 Fazola, Irving 241 Hall, Edmond 242 Burke, Ray 243 Frazier, “Cie” 245 French, “Papa” 256 Dolly Adams 2 3 Dolly‟s parents were Louis Douroux and Olivia Manetta Douroux. It was a musical family on both sides. Louis Douroux was a trumpet player. His brother Lawrence played trumpet and piano and brother Irving played trumpet and trombone. Placide recalled that Irving was also an arranger and practiced six hours a day. “He was one of the smoothest trombone players that ever lived. He played on the Steamer Capitol with Fats Pichon‟s Band.” Olivia played violin, cornet and piano. Dolly‟s uncle, Manuel Manetta, played and taught just about every instrument known to man.