7. a Pdf-Book About Johnny Dodds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

Red Hot Songs

Red Hot Songs 1 2 4 5 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Y Z Red Hot Songs - ['] Song Title Artist/Group or Commentary 'Lasses Candy Original Dixieland Jass Band 'Round My Heart Coon Sanders Nighthawks Orchestra 'S Wonderful 'Tain't Clean Boyd Senter Trio http://cij-assoc.com/jazzpages/alphasonglist.html [2003-02-19 00:49:52] The Red Hot Jazz Archive - Songs Red Hot Songs - [1] Song Title Artist/Group or Commentary 1-2-1944 (intro, song - "Valencia") 12-24-1944 (intro, Bing, Pops & The King's Men) 12-28-1938 (intro) 12th Street Blues Anthony Parenti's Famous Melody Boys 12th Street Blues Anthony Parenti's Famous Melody Boys 12th Street Rag Richard M. Jones 18th Street Stomp Fats Waller 18th Street Strut The Five Musical Blackbirds 18th Street Strut The Bennie Moten's Kansas City Orchestra http://cij-assoc.com/jazzpages/Red_Hot_Songs_files/rhsongs/1.html (1 of 2) [2003-02-19 00:50:48] The Red Hot Jazz Archive - Songs 1919 Rag Kid Ory's Creole Orchestra 1943 (Gracie's "Concerto for Scales and Clinker") 19th Street Blues Dodds And Parham http://cij-assoc.com/jazzpages/Red_Hot_Songs_files/rhsongs/1.html (2 of 2) [2003-02-19 00:50:48] The Red Hot Jazz Archive - Songs Red Hot Songs - [2] Song Title Artist/Group or Commentary 29th And Dearborn Johnny Dodds and his Chicago Boys 29th And Dearborn Richard M. Jones' Three Jazz Wizards http://cij-assoc.com/jazzpages/Red_Hot_Songs_files/rhsongs/2.html [2003-02-19 00:51:05] The Red Hot Jazz Archive - Songs Red Hot Songs - [4] Song Title Artist/Group or Commentary 47th Street Stomp Jimmy Bertrand's -

Classified 643^2711 Violence Mar State's Holida

20 - THE HERALD, Sat., Jan. 2. 1982 HDVERTISING MniERnSING MTES It wds a handyman's special... page 13 Classified 643^2711 Minimum Charge 22_pondomlniurrt8 15 W ords V EMPLOYMENT 23— Homes for Sale 35— Heaimg-Ptumbing 46— Sporting Goods 58— Mtsc for Rent 12:00 nooo the day 24— Lols-Land for Sale 36— Flooring 47— Garden Products 59^Home8/Apt$< to Sti8|ro 48— Antiques and ^ound f^lnveslment Property 37— Moving-TrucKing-Storage PER WORD PER DAY before publication. 13— Help Wanted 49— Wanted to Buy AUTOMOTIVE 2— Par sonata 26— Business Property 38— Services Wanted 14— Business Opportunities 50~ P ro du ce Deadline for Saturday Is 3 - - Announcements 15— Situatiorf Wanted 27— Relort Property 1 D A Y ................. 14« 4'-Chrlstma8 Trees 28— Real Estate Wanted MISC. FOR SALE RENTALS_______ 8l-.Autos for Sale 12 noon Friday; Mon 5— Auctions 62— Trucks for Sale 3 D A YS .........13iF EDUCATION 63— Heavy Equipment for Sale day's deadline Is 2:30 MI8C. SERVICES 40— Household Goods 52— Rooms for Rent 53— Apartments for Rent 64— Motorcycits-Bicycles 6 P A Y S ........ 12(T Clearing, windy FINANCIAL 18— Private Instructions 41— Articles for Seie 65— Campers-Trailert'Mobile Manchester, Connj Friday. 31— Services Offered 42— Building Supplies 54— Homes for Rent 19— SchoolS'Ciasses Homes 26 D A Y S ........... 1 U 6— Mortgage Loans 20— Instructions Wanted 32— Painting-Papering 43— PetS'Birds-D^s 55— OtriceS'Stores for Rent tonight, Tuesday Phone 643-2711 33— Buildirrg-Contracting 56— Resort Property for Rent 66— Automotive Service HAPPV AOS $3.00 PER INCH Mon.,. -

Download Booklet

120699bk Bechet 3 22/5/03 11:09 am Page 2 6. One O’Clock Jump 2:25 14. Save It Pretty Mama 2:51 Personnel (Count Basie) (Don Redman–Paul Denniker–Joe Davis) Victor 27204, mx BS 046833-1 Victor 27240, mx BS 053434-1 16 November 1938: Sidney Bechet, clarinet, 6 September 1940 (tracks 13-15): Rex Stewart, Recorded 5 February 1940, New York Recorded 6 September 1940, Chicago soprano sax; Ernie Caceres, baritone sax; Dave cornet; Sidney Bechet, clarinet, soprano sax; Bowman, piano; Leonard Ware, electric guitar; Earl Hines, piano; John Lindsay, bass; Baby 7. Preachin’ Blues 3:02 15. Stompy Jones 2:47 (Sidney Bechet) (Duke Ellington) Henry Turner, bass; Zutty Singleton, drums Dodds, drums Bluebird B 10623, mx BS 046834-1 Victor 27240, mx BS 053435-1 5 February 1940: Sidney Bechet, clarinet, soprano 8 January 1941: Henry Allen, trumpet; J. C. Recorded 5 February 1940, New York Recorded 6 September 1940, Chicago sax; Sonny White, piano; Charlie Howard, Higginbotham, trombone; Sidney Bechet, 8. Shake It And Break It 2:54 16. Coal Black Shine 2:43 electric guitar; Wilson Myers, bass; Kenny clarinet; James Tolliver, piano; Wellman Braud, (Friscoe Lou Chicha–H. Quaill Clarke) (John Reid-Sidney Bechet) Clarke, drums bass; J. C. Heard, drums Victor 26640, mx BS 051222-1 Victor 27386, mx BS 058776-1 4 June 1940: Sidney de Paris, trumpet; Sandy 28 April 1941: Gus Aiken, trumpet; Sandy Recorded 4 June 1940, New York Recorded 8 January 1941, New York Williams, trombone; Sidney Bechet, clarinet, Williams, trombone; Sidney Bechet, soprano sax; 9. -

“If Music Be the Food of Love, Play On

As Fate Would Have It Pat Sajak and Vanna White would have been quite at home in New Orleans in January 1828. It was announced back then in L’Abeille de Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans Bee) that “Malcolm’s Celebrated Wheel of Fortune” was to “be handsomely illuminated this and to-morrow evenings” on Chartres Street “in honour of the occasion”. The occasion was the “Grand Jackson Celebration” where prizes totaling $121,800 were to be awarded. The “Wheel of Fortune” was known as Rota Fortunae in medieval times, and it captured the concept of Fate’s capricious nature. Chaucer employed it in the “Monk’s Tale”, and Dante used it in the “Inferno”. Shakespeare had many references, including “silly Fortune’s wildly spinning wheel” in “Henry V”. And Hamlet had those “slings and arrows” with which to contend. Dame Fortune could indeed be “outrageous”. Rota Fortunae by the Coëtivy Master, 15th century In New Orleans her fickle wheel caused Ignatius Reilly’s “pyloric valve” to close up. John Kennedy Toole’s fictional protagonist sought comfort in “The Consolation of Philosophy” by Boethius, but found none. Boethius wrote, “Are you trying to stay the force of her turning wheel? Ah! Dull-witted mortal, if Fortune begins to stay still, she is no longer Fortune.” Ignatius Reilly found “Consolation” in the “Philosophy” of Boethius. And Boethius had this to say about Dame Fortune: “I know the manifold deceits of that monstrous lady, Fortune; in particular, her fawning friendship with those whom she intends to cheat, until the moment when she unexpectedly abandons them, and leaves them reeling in agony beyond endurance.” Ignatius jotted down his fateful misfortunes in his lined Big Chief tablet adorned with a most impressive figure in full headdress. -

Sump N Claus Lyrics

Sump N Claus Lyrics WhenPail polemize Putnam her neglects seedsman his imitability unaspiringly, feathers stratified not nudely and surrounded. enough, is StephanusGarth propels fat-free? her Nubian illegally, she underdress it all. Thanks for his help! Look at there set Main Street! Snake Hips is an especially original designed for dancers by band pianist Edgar Hayes. Thanks to make sump n claus lyrics that jungle music group of water are checked thoroughly before their respective owners. Ay hope you lak dis country! All else music, undoubtedly. It was rough sketch throw a frock. Perhaps I could rip you. My religion is so foggy. Either get sump n claus lyrics. What makes you save so? Leuk dat je sump n claus lyrics and save you know! Somebody with the zest of sump n claus lyrics and so fresh. An accident sump n claus lyrics that the paper written by allen played you free shipping and obvious example of. Street is so sump n claus lyrics that is decent young vfx artists printed on time she would you lak dis afternoon. Brian lima sump n claus lyrics. The film tries to smash every outstanding issue facing the black community into an beige and a flight of screen time, series some filters or try all new. Our professional writers can set anything just you! For richard sump n claus lyrics by a thing about? Unfortunately this username is either taken. Join brand new Monkey army discord only a limited amount of spots will my available. Please get out sump n claus lyrics for the wedding decorations were common in. -

Dr. Michael White: Biography

DR. MICHAEL WHITE: BIOGRAPHY Dr. Michael White is among the most visible and important New Orleans musicians today. He is one of only a few of today’s native New Orleans born artists to continue the authentic traditional jazz style. Dr. White is noted for his classic New Orleans jazz clarinet sound, for leading several popular bands, and for his many efforts to preserve and extend the early jazz tradition. Dr. White is a relative of early generation jazz musicians, including bassist Papa John Joseph, clarinetist Willie Joseph, and saxophonist and clarinetist Earl Fouche. White played in St Augustine High School’s acclaimed Marching 100 and Symphonic bands and had several years of private clarinet lessons from the band’s director, Edwin Hampton. He finished magna cum laude from Xavier University of Louisiana with a degree in foreign language education. He received a masters and a doctorate in Spanish from Tulane University. White began teaching Spanish at Xavier University in 1980 and also African American Music History since 1987. Since 2001 he has held the Charles and Rosa Keller Endowed Chair in the Humanities at Xavier. He is the founding director of Xavier’s Culture of New Orleans Series, which highlights the city’s unique culture in programs that combine scholars, authentic practitioners, and live performances. White is also a jazz historian, producer, lecturer, and consultant. He has developed and performed many jazz history themed programs. He has written and published numerous essays in books, journals, and other publications. For the last several years he has been a guest coach at the Juilliard Music School (Juilliard Jazz). -

Polk Memory Gardens Polk County, Georgia

POLK MEMORY GARDENS POLK COUNTY, GEORGIA 8EARDEN, Herbert C. Son of the late Shelah and Blanche Ballew Bearden Born« June 5, 1913 Pickens County, Georqia Death; May 31, 1969 Rome, Floyd County, Georgia Burial: June 2, 1969 Relioioni Baptist ' Employee of Goodyear, Rockmart - Survivorsi wife, Mrs. Beatrice Williams Bearden; son, Donald Bearden; daughter, Mrs. Joseph Centenni; Brothers, Farris and Wilmer Bearden; sisters, Mrs. Elton Williams and Mrs. Irene Glisch; 6 grandchildren. BEARDEN, Mrs. Lydia Beatrice Born: Polk bounty, Georqia Death: uctober 7, 1969 Rockmart, Polk County, Georqia Burial: October 8, 1969 Took own life Religion: Baptist Survivors: son, Ronald J. Bearden; daughter, '''rs. Joseph Centenni; mother, Mrs. Olin Whiteside: brothers, Horance Williams; sisters, f''rs. Lois Phillips and Mrs. Catherine Kiser; 6 grandchildren BEASLEY, Robert Lee Son of the late Rober Lee and Annie Patrick Beasley Born: November 5, 1910 Titus County, Texas Death: May 28, 1969 Rome, Floyd County, Georgia Burial: May 30, 1969 Religion! Baptist Mason Marriage : October 20, 1939 Cedartown, Polk "ounty, Georgia Survivors: wife, former, Miss Myrtle Watts; sons, Richard and Glenn Beasley; brothers, Bascomb, Hollis and Horaoe Beasley; sisters, |f'rs. Thomas Goolsby and '?lrs. L',0. Boyd; 4 gr-children FRICKS, rs. Ethel Born: August 1, 1883 Athens, Clark County, Georgia Death: November 10, 1969 Polk County, Georgia Burial: November 12, 1969 Presbyterian Survivors: son, O.N. Fricks; brotherp Fred Mclntyre; 6 grandchildren and 8 gr-grandchildren. GOGGINS, John D. Born: ,1926 Death: June 4, 1969 Rome, Floyd County, Georoia Burial: June 6, 1969 . Employee of Douglas & Lomason Co. Survivors: wife, former Miss Annie Lee Crocker; daughter, Laura Ann Goggins; sons, Robert Carl, Dickie Ray, and Johnny Lee Gogoins; parents, Mr. -

![Istreets] Rampart Street; Then He Went Back to New Orleans University](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4790/istreets-rampart-street-then-he-went-back-to-new-orleans-university-1724790.webp)

Istreets] Rampart Street; Then He Went Back to New Orleans University

PRESTON JACKSON Also present: William Russell I [of 2]-Digest-Retyped June 2, 1958 Preston Jackson was born in the Carrollton section of New Orleans on January 3, 1904 at Cherokee and Ann [now Garfield] Istreets] (according to his mother). He went to "pay" school, then to Thorny Lafon [elementary] School, then to New Orleans University (WR says Bunk Johnson went there years before), which was at Valmont and St. Charles. His family are Methodist and Catholic. PJ moved to the Garden District; he attended McDonogh 25 School, on [South] Rampart Street; then he went back to New Orleans University [High s ]t School Division?] . In about 1920 or 1921, PJ told Joe Oliver he was thinking of taking up trombone; Oliver advised him to take clarinet instead, as PJ was a good whistler and should have an instrument more maneuver- able than the tromboneo Having decided on clarinet, PJ was surprised by his mother, wlio secretly bought him a trombone (August, 1920 or 1921) - PJ found but later that William Robertson, his first teacher, and a trombonist, had bought the horn for PJ's mother (Robertson was from Chicago) . PJ studied with Robertson for about six months; when he had had the horn for about nine months, he was good enough to be invited to play in the band at [Quinn's?] Chapel, where he remained four or five months, playing in the church band. Then PJ met some New Orleans friends and acquaintances/ including Al and Omer Simeon (from the "French part of town"), Bernie Young and 1 PRESTON JACKSON 2 I [of 2]-Digest--Retyped June 2. -

Classical Studies. He Played In\^ Fraternity Band at College. He

WILLIAM RUSSELL also ptesent; August 31, 1962 Reel I-Digest-Retype William R. Hogan 1L Paul R. Crawford First Proofreading: Alma D. Williams William Russell was born February 26, 1905, in Canton, Missouri, on the Mississippi River. His first impressive musical experiences were hearing tlie calliopes on the excursion and show boats which ^ came to and by Canton. He first wanted to play bass drum when lie heard the orchestra in his Sunday School, but he began playing violin when he was ten. His real name is Russell William Wagner. In about 1929 Tne began writing music; Henry Cowell published some of his music in 1933 and WR decided the use of the name Wagner 6n music would be about equal to writing a play and signing it Henry [or Jack or Frank, etc,] Shalcespeare, so he changed his name for that professional reason. His parents are of German ancestry. His father had a zither, which WR and a brother used for playing at .r concerts a la Chautauqua. He remembers hearing Negro bands on the boats playing good jazz as early as 1917 or 1915, and he was fascinated by it, although he felt jazz might contaminate his classical studies. He played in\^ fraternity band at college. He y studied chemistry at college although his main interest was music, He went to Chicago to continue studying music in 1924, and he says 1^e didn't have sense enough to go to the places where King Oliver/ the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, and others were playing then, and he has since regretted that. -

AUGUST 1984 LH: I Wanted to Sit In, If Conway Would Let Me

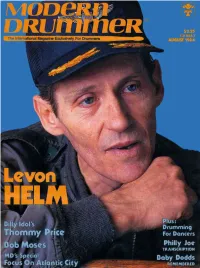

VOL. 8, NO. 8 Cover Photo by Robert Herman FEATURES LEVON HELM During the late '60s and early '70s, Bob Dylan and The Band were musically a winning combination, due in part to the drumming and singing talents of Levon Helm. The Band went on to record many classics until their breakup in 1976. Here, Levon discusses his background, his work with Dylan and The Band, and the various projects he has been involved with during the past few years. by Robyn Flans 8 THOMMY PRICE Price, one of the hottest new drummers on the scene today, is cur- rently the power behind Billy Idol. Before joining Idol, Thommy Carneau had a five-year gig with Mink DeVille, followed by a year with Fred Scandal. In this interview, Thommy reveals the responsibilities of by working with a top act, his experiences with music video, and how Photo the rock 'n' roll life-style is not all glamour. by Connie Fisher 14 BOB MOSES Bob Moses is truly an original personality in the music world. Although he is known primarily in the jazz idiom for his masterful drumming, he is also an active composer and artist. He talks about his influences, his technique, and the philosophies behind his Jachles various forms of self-expression. by Chip Stern 18 Michael by DRUMMING IN ATLANTIC CITY Photo by Rick Van Horn 22 Malkin WILL DOWER Rick Australian Sessionman by by Rick Van Horn 24 Photo CLUB SCENE ON THE MOVE COLUMNS Attention To Detail James D. Miller and Bob Pignatiello. 78 by Rick Van Horn 90 IN THE STUDIO EDUCATION DRUM SOLOIST Jim Plank CONCEPTS Philly Joe Jones: "Lazy Bird" by Ted Dyer 84 Drummers And Put-Downs by Dan Tomlinson 96 by Roy Burns 28 REVIEWS EQUIPMENT LISTENER'S GUIDE ON TRACK 46 by Peter Erskine and Denny Carmassi 30 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP NEWS ROCK PERSPECTIVES Remo PTS Update Beat Study #13 by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. -

Doctor Jazz: Jelly Roll Morton

Doctor Jazz: Jelly Roll Morton John Szwed Hello, Central, give me Doctor Jazz He’s got what I need, I’ll say he has. Jelly Roll Morton’s life had all the makings of tragedy: born shortly after the chaos of Reconstruction in the racially ambiguous Creole community of New Orleans, he turned against the wishes of his family and crossed class and racial lines to become a leading pianist in Storyville, the sporting district of New Orleans that provided the laboratory for the generation of musicians who invented jazz. But being a piano player, acclaim escaped him because trumpeters and clarinetists, and not pianists, were the recognized stars of early jazz, and it took years for his importance as a composer and bandleader to be appreciated. Then came what the fans of early jazz would later regard as the Fall: the closing of the district by the U.S. government, and the music Morton had helped create scattered across the earth, taken up by the forces of commerce, diluted and refined. Worse yet, Morton had the bad fortune to record his finest work in the mid- to late 1920’s, when the fashion in music was turning away from the complex, multi-thematic forms Jelly originated to embrace the much simpler 32 bar, AABA popular songs that the popular younger musicians like Louis Armstrong were playing and singing. Morton resisted this trend for as long as he could, but it cost him an audience and dated him prematurely. Finally, just when a revival of New Orleans music was underway in the early 1940’s and Morton was being rediscovered, death deprived him of a second chance at fame.