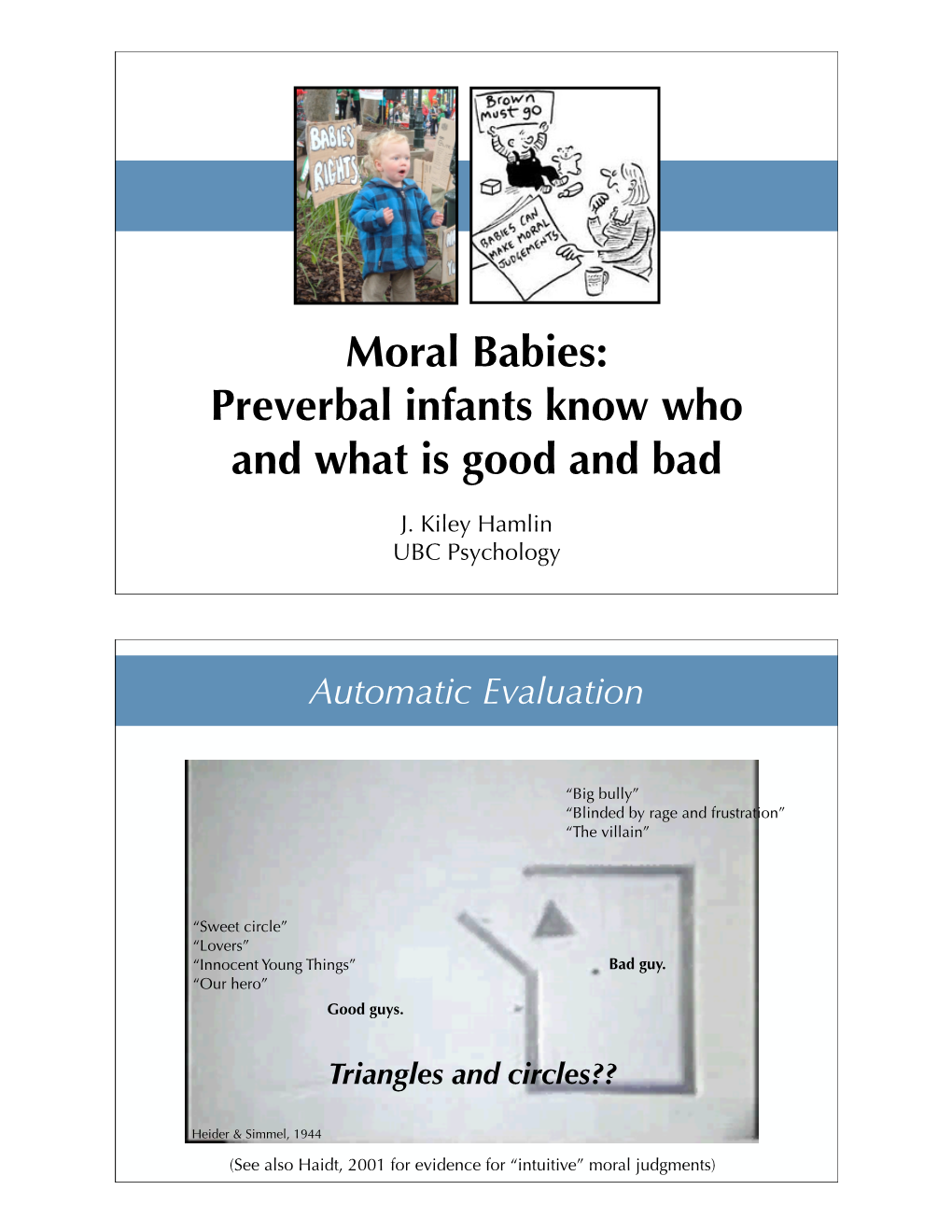

Moral Babies: Preverbal Infants Know Who and What Is Good and Bad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Findings of Addition and Subtraction in Infants Are Robust and Consistent: Reply to Wakeley, Rivera, and Langer

Child Development, November/December 2000, Volume 71, Number 6, Pages 1535–1536 Findings of Addition and Subtraction in Infants Are Robust and Consistent: Reply to Wakeley, Rivera, and Langer Karen Wynn Findings showing numerical computation abilities in infants are considerably more robust and consistent than Wakeley, Rivera, and Langer suggest. All the interim replication attempts have successfully replicated my orig- inal findings. Possible reasons for Wakeley et al.’s failure to replicate are discussed. INTRODUCTION findings—which were themselves obtained across three experiments in the original report. In Wynn (1992a), I reported findings that young in- As Wakeley et al. (2000) discuss, some studies have fants could determine the outcomes of simple addi- reported failures of infants to discriminate numeri- tion and subtraction operations; across three experi- cally correct from incorrect outcomes to addition and ments, 5-month-olds looked longer at numerically subtraction events, but these studies have tested other incorrect than correct outcomes of addition (1 1 1) abilities, presenting infants with different events from and subtraction (2 2 1) situations. In their article in those in the above experiments. The failures reported this issue, Wakeley, Rivera, and Langer present a suggest possible limitations to (1) the set sizes that in- failure to replicate these findings. Based on these re- fants can accurately operate over (Baillargeon, 1994; sults as well as those of other experiments, they Wynn, 1995), (2) the number of mental “updates” in- conclude that infants’ ability to compute results of fants can perform on an unseen set (Baillargeon, 1994; simple additions and subtractions is fragile and Uller et al., 1999), and (3) the numerical values that in- inconsistent. -

Newsletter Philippe Rochat Was Born and Raised in Geneva, Spring 2013 Switzerland

Emory Infant and Child Meet the Lab: Development Research Laboratory Philippe Rochat Newsletter Philippe Rochat was born and raised in Geneva, Spring 2013 Switzerland. He was trained by Jean Piaget understand prejudice and minority and his close psychology, Bentley Gibson is now testing the collaborators, and implicit and explicit social attitudes of African received his Ph.D. from Letter to Parents: American adults and children toward other the University of Geneva, and own racial groups. This is something that Switzerland in 1984. He is not well documented and should yield Article by: Philippe Rochat Ph.D. then began a series of Head of the Emory Infant and Child Lab important information. We will be able to report new findings in the next Newsletter. Post Doctoral internships Our mission at the Infant and Child Lab is Supervised and spearheaded by Theresa at Brown University, the to contribute to the understanding of how Moehrle (Lab coordinator), we also finished University of children develop. Ultimately, all research investigating the propensity of 3-7 year-old Pennsylvania, and Johns conducted at the Lab is geared toward a children from various ethnic origins to engage better approximation of what seems to drive in so-called “stigma by association” based on Hopkins. The main focus our psychology, one that begins to prior to skin color. For example, does a child prefer a of his research is the birth and continues to develop all through black doll that is depicted as being friends early sense of self, the lifespan. with a white doll rather than a black doll? emerging self-concept, The past year has been particularly The data we analyzed yielded little evidence the development of fruitful. -

Still Measuring up the Remarkable Story of René Syler in Her Own Words

Still Measuring Up The remarkable story of René Syler in her own words Presort Standard US Postage PAID Permit No. 161 Journal, Spring 2008Harrisonburg, | www.nabj.org VA | National Association of Black Journalists | 1 2 | National Association of Black Journalists | www.nabj.org | Journal, Spring 2008 Features 8 – Thomas Morgan III: A life remembered. 18 – Out of the Mainstream: TV One’s Cathy Hughes on race, presidential politics, and oh yeah, dominating the airwaves. 20 – Fade to white: In a revealing, personal memoir, Lee Thomas takes readers on a journey of change. 33 – Internships: Now that you have one, here is how to keep it and succeed. Africa 22 – Back to Africa: Seven NABJ members traveled to Senegal late last year to tell the stories of climate change, HIV/AIDS, disease and education. Here are their stories. 26 – Ghana: Bonnie Newman Davis, one of NABJ’s Ethel Payne Fellows explores why Ghana is everything she thought it would be. Digital Journalism Three veteran digital journalists, Andrew Humphrey, Ju-Don Marshall Rob- erts and Mara Schiavocampo, dig through the jargon to decode the digital revolution. 28 – The Future is Here 30 – Tips for Media Newbies 30 – As newsrooms change, journalists adjust Cover Story The NABJ Journal looks at the issue of breast cancer through the eyes of our members. 10 – New Year’s Resolutions: René Syler goes first person to discuss her difficult year and her prospects for the future. 15 – No fear: NBC’s Hoda Kotb gains strength in battle against cancer. 16 – Out in the open: Atlanta’s JaQuitta Williams on why it was important to share her story with others. -

The Moral Baby

20 The Moral Baby Karen Wynn and Paul Bloom Most developmental research into morality so far has focused on children and adolescents, as can be seen in the contributions of this current volume. We think that the time is ripe to take a serious look at the moral lives of babies. One motivation for this comes from evolutionary theory. Biologists have long been interested in how a species like ours—in which large groups of nonkin work together on projects of mutual benefit—could come to exist. This was largely a mystery at the time of Darwin, but there are by now several candidate theories for how our complex social structures can arise. These include the accounts developed in the 1970s and 1980s based on kin selection and reciprocal altruism (e.g., Axelrod, 1984; Trivers, 1971, 1985), as well as theories based on group selection—a proposal once derided by biologists, but now returning as a serious contender (see Nowak & Highfield, 2011, for an accessible review). Such theories explain our complex social structures as grounded in certain propensities that we can view as moral, including altruism to nonkin, guilt at betraying another, and righteous anger toward cheaters. While the details are a matter of considerable debate, the notion of unlearned moral universals is consistent with what we now know about bio- logical evolution. And one way to explore the nature of such universals is to look at babies. The second motivation comes from developmental psychology. Over the last 30 or so years, findings based on looking-time methods set off a revolution in how we think about the minds of babies. -

FAST-TRACK REPORT Interrupting Infants' Persisting Object

Developmental Science 9:5 (2006), pp F50–F58 FAST-TRACKBlackwell Publishing Ltd REPORT Interrupting infants’ persisting object representations: an object-based limit? Erik W. Cheries, Karen Wynn and Brian J. Scholl Department of Psychology, Yale University, USA Abstract Making sense of the visual world requires keeping track of objects as the same persisting individuals over time and occlusion. Here we implement a new paradigm using 10-month-old infants to explore the processes and representations that support this ability in two ways. First, we demonstrate that persisting object representations can be maintained over brief interruptions from additional independent events – just as a memory of a traffic scene may be maintained through a brief glance in the rearview mirror. Second, we demonstrate that this ability is nevertheless subject to an object-based limit: if an interrupting event involves enough objects (carefully controlling for overall salience), then it will impair the maintenance of other persisting object representations even though it is an independent event. These experiments demonstrate how object representations can be studied via their ‘interruptibility’, and the results are consistent with the idea that infants’ persisting object representations are constructed and maintained by capacity-limited mid-level ‘object-files’. Introduction individuals, objects must: (1) trace spatiotemporally continuous paths through space and time (Aguiar & Coherent visual experience depends not only on our Baillargeon, 1999, 2002; Bremner, Johnson, Slater, ability to bind individual visual features into discrete Mason, Foster, Cheshire & Spring, 2005; Flombaum, object representations, but also on our ability to bind Kundey, Santos & Scholl, 2004; Flombaum & Scholl, multiple views of objects over time and motion into the in press; Michotte, Thinès & Crabbé, 1964/1991; Scholl same persisting object representations. -

Infants Fail to Match the Food Preferences of Antisocial Others

Cognitive Development 27 (2012) 227–239 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Cognitive Development Who knows what’s good to eat? Infants fail to match the food preferences of antisocial others a,∗ b J. Kiley Hamlin , Karen Wynn a Department of Psychology, The University of British Columbia, 2136 West Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada b Department of Psychology, Yale University, 2 Hillhouse Ave, New Haven, CT 06511, United States a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Keywords: Humans gather most of their knowledge about the world, includ- Social evaluation ing objectively true facts and specific cultural norms, by observing Social learning/imitation and being taught by others. Some individuals are worthy teach- Negativity bias ers and objects of imitation, having knowledge of cultural practices and positive intentions to inform. Others are better ignored because they are ignorant, because they mean us harm, or simply because we do not wish to be “like them.” This study examines whether 16-month-olds are sensitive to the pro- or antisocial behavior of a source that demonstrates preference for two novel foods. Infants took the emotional reactions displayed by novel and previously prosocial sources, but not antisocial sources, into account when deciding what to eat. These results suggest that others’ social behavior influences infants’ likelihood to match their preferences, illustrating the influence of social evaluation on social learning. © 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Most of what we know comes from others. By observing and interacting with others socially, we gain a wealth of information required for successful existence, from the language and cultural practices of our social group to the workings of a particular piece of complex machinery. -

Curriculum Vitae Yuko Munakata

Curriculum Vitae Yuko Munakata Business Address: Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, 345 UCB University of Colorado Boulder Boulder, CO 80309-0345 (303)735-5499 (voice)/492-2967 (fax) [email protected] www.colorado.edu/munakata Employment Professor, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Colorado Boulder, 2007-present. Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Colorado Boulder, 2002-2007. Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Denver, 2001-2002. Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Denver, 1997-2001. Degrees Ph.D., Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University, 1996. Thesis: “Adaptive Processes in Cognitive Change: A Unified Framework for Understanding Infants’ Successes and Failures in Object Permanence Tasks”. James L. McClelland advisor. M.S., Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University, 1993. B.A. with Honors, with Distinction, Psychology, Stanford University, 1991. B.S., Symbolic Systems, Stanford University, 1991. Additional education McDonnell-Pew Program in Cognitive Neuroscience Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sci- ences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1996-1997. Interdisciplinary program in Neural Processes in Cognition, University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University, 1992-1996. McDonnell Summer Institute in Cognitive Neuroscience, Dartmouth College, 1992. Research interests Executive functions and their development Social and environmental influences on cognition Implications for intervention Yuko Munakata 2 Honors and awards Faculty Research Award, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Colorado Boulder, 2017. Outstanding Mentor Award, University of Colorado Boulder Office of Postdoctoral Affairs, 2016. Faculty Teaching Award, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Colorado Boulder, 2015. Best Digital Management Plans and Practices Award, Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, University of Colorado Boulder, 2014. -

2011 State of the News Media Report

Overview By Tom Rosenstiel and Amy Mitchell of the Project for Excellence in Journalism By several measures, the state of the American news media improved in 2010. After two dreadful years, most sectors of the industry saw revenue begin to recover. With some notable exceptions, cutbacks in newsrooms eased. And while still more talk than action, some experiments with new revenue models began to show signs of blossoming. Among the major sectors, only newspapers suffered continued revenue declines last year—an unmistakable sign that the structural economic problems facing newspapers are more severe than those of other media. When the final tallies are in, we estimate 1,000 to 1,500 more newsroom jobs will have been lost—meaning newspaper newsrooms are 30% smaller than in 2000. Beneath all this, however, a more fundamental challenge to journalism became clearer in the last year. The biggest issue ahead may not be lack of audience or even lack of new revenue experiments. It may be that in the digital realm the news industry is no longer in control of its own future. News organizations — old and new — still produce most of the content audiences consume. But each technological advance has added a new layer of complexity—and a new set of players—in connecting that content to consumers and advertisers. In the digital space, the organizations that produce the news increasingly rely on independent networks to sell their ads. They depend on aggregators (such as Google) and social networks (such as Facebook) to bring them a substantial portion of their audience. And now, as news consumption becomes more mobile, news companies must follow the rules of device makers (such as Apple) and software developers (Google again) to deliver their content. -

COMMENTARIES Evidence for Numerical Abilities in Young Infants

202 Commentaries COMMENTARIESBlackwell Publishers Ltd EvidenceCommentaries for numerical abilities in young infants: a fatal flaw? Susan Carey Harvard University, USA Wynn’s (1992) well-known and oft-replicated1 Nature tion when attributing sophisticated abilities, such as the paper established that 4-month-old infants look longer capacity to add and subtract, to very young infants. at impossible than at possible outcomes in ‘addition’ and Although Cohen and Marks’ remarks are aimed at ‘subtraction’ events. In a 1 + 1 addition event, for Wynn’s proposals, their data bear equally on the other instance, the infant was shown a single object on a stage, major interpretation of the infant addition/subtraction which was then covered by a screen. A second object was data, called the ‘object file’ model by Uller, Huntley- then introduced behind the screen and the screen then Fenner, Carey and Klatt (1999). According to the object was lowered, revealing either the possible outcome of 2 file model, infants establish a representation of each objects or an impossible outcome of 1 object. In this individual object behind the screen, updating these rep- 1 + 1 = 2 or 1 event, infants looked longer at the imposs- resentations as objects are added to or subtracted from ible outcome of 1 object. Similarly, infants look longer the set (see also Scholl & Leslie, 1999; Simon, 1997). The at the impossible outcome in a 2 − 1 = 2 or 1 subtraction representation of the updated hidden set is compared to event or a 1 + 1 = 2 or 3 addition event. the set of objects revealed when the screen is removed on Wynn took these findings to show that very young the basis of 1–1 correspondence, a computation that infants symbolically represent the number of hidden established numerical equivalence (but see Feigenson, objects behind screens, and can operate on symbolic rep- Carey & Spelke, in press, and Feigenson, Carey & resentations of number by adding or subtracting 1, Hauser, in press). -

Limits to Early Altruism

CDPXXX10.1177/0963721417734875Wynn et al.Not Noble Savages After All 734875research-article2017 Current Directions in Psychological Science Not Noble Savages After All: Limits 1 –6 © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: to Early Altruism sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417734875 10.1177/0963721417734875 www.psychologicalscience.org/CDPS Karen Wynn, Paul Bloom, Ashley Jordan, Julia Marshall, and Mark Sheskin Department of Psychology, Yale University Abstract Many scholars draw on evidence from evolutionary biology, behavioral economics, and infant research to argue that humans are “noble savages,” endowed with indiscriminate kindness. We believe this is mistaken. While there is evidence for an early-emerging moral sense—even infants recognize and favor instances of fairness and kindness among third parties—altruistic behaviors are selective from the start. Babies and young children favor people who have been kind to them in the past and favor familiar individuals over strangers. They hold strong biases for in-group over out-group members and for themselves over others, and indeed are more unequivocally selfish than older children and adults. Much of what is most impressive about adult morality arises not through inborn capacities but through a fraught developmental process that involves exposure to culture and the exercise of rationality. Keywords morality, development, altruism In Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes (1651/2006) famously concerns such as fairness and reciprocity (see Starmans, claimed that humans are born selfish and vicious—in Sheskin, & Bloom, 2017, for a review). the absence of cultural rules and societal restraints, life Much of the swing from Hobbes to Rousseau has is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (pp. -

Ashley Eliza Jordan Curriculum Vitae

Jordan CV Sept. 2020 p.1 Ashley Eliza Jordan Curriculum Vitae Contact Information Princeton University E-mail: [email protected] Department of Psychology Web: ashleyelizajordan.com Peretsman Scully Hall, Rm 110 Phone: 609-258-4442 Princeton, NJ 08540 Education 2015 – 2020 Ph.D., Developmental Psychology Yale University, New Haven, CT (Advisors: Karen Wynn, Yarrow Dunham) 2008 – 2011 B.A., Psychology University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 2006 – 2008 Madison College, Madison, WI Academic Appointments Fall 2020 – Postdoctoral Fellow, Human Diversity Lab, Dept. of Psychology Princeton University, Princeton, NJ (PI: Kristina Olson) Selected Fellowships & Awards Samuel K. Bushnell Graduate Fellowship, Yale University, 2019-2020 Conference Travel Award, Graduate Student Assembly, Yale University, 2019 Helen Peak Graduate Fellowship, Yale University, 2018 – 2019 Travel Award, Cognitive Development Society, 2017 Ford Foundation, Predoctoral Fellowship Program, Honorable Mention, 2016, 2017 National Science Foundation, Graduate Research Fellowship, Honorable Mention, 2016, 2017 Travel Award, Cognitive Development Society, 2015 Jordan CV Sept. 2020 p.2 Manuscripts Jordan, A.E., & Wynn, K. Adults’ pedagogical messages engender children’s preference for self-resembling others (under review). Jordan, A.E., Kalish, C., Brey, E., & Shutts, K. Detecting social groups: How visual cues acquire social meaning (under revision). Jordan, A.E., & Dunham, Y. Children’s affiliation inferences when group membership and shared preferences conflict (in prep). Publications Jordan, A.E., & Dunham, Y. (in press). Are category labels primary? Children use similarities to reason about social groups. Developmental science. Wynn, K., Bloom, P., Jordan, A., Marshall, J., & Sheskin, M. (2018). Not noble savages after all: Limits to early altruism. Current directions in psychological science, 27(1), 3-8. -

The Moral Life of Babies by PAUL BLOOM

The New York Times 1 May 5, 2010 The Moral Life of Babies By PAUL BLOOM Not long ago, a team of researchers watched a 1-year-old boy take justice into his own hands. The boy had just seen a puppet show in which one puppet played with a ball while interacting with two other puppets. The center puppet would slide the ball to the puppet on the right, who would pass it back. And the center puppet would slide the ball to the puppet on the left . who would run away with it. Then the two puppets on the ends were brought down from the stage and set before the toddler. Each was placed next to a pile of treats. At this point, the toddler was asked to take a treat away from one puppet. Like most children in this situation, the boy took it from the pile of the “naughty” one. But this punishment wasn’t enough — he then leaned over and smacked the puppet in the head. This incident occurred in one of several psychology studies that I have been involved with at the Infant Cognition Center at Yale University in collaboration with my colleague (and wife), Karen Wynn, who runs the lab, and a graduate student, Kiley Hamlin, who is the lead author of the studies. We are one of a handful of research teams around the world exploring the moral life of babies. Like many scientists and humanists, I have long been fascinated by the capacities and inclinations of babies and children. The mental life of young humans not only is an interesting topic in its own right; it also raises — and can help answer — fundamental questions of philosophy and psychology, including how biological evolution and cultural experience conspire to shape human nature.