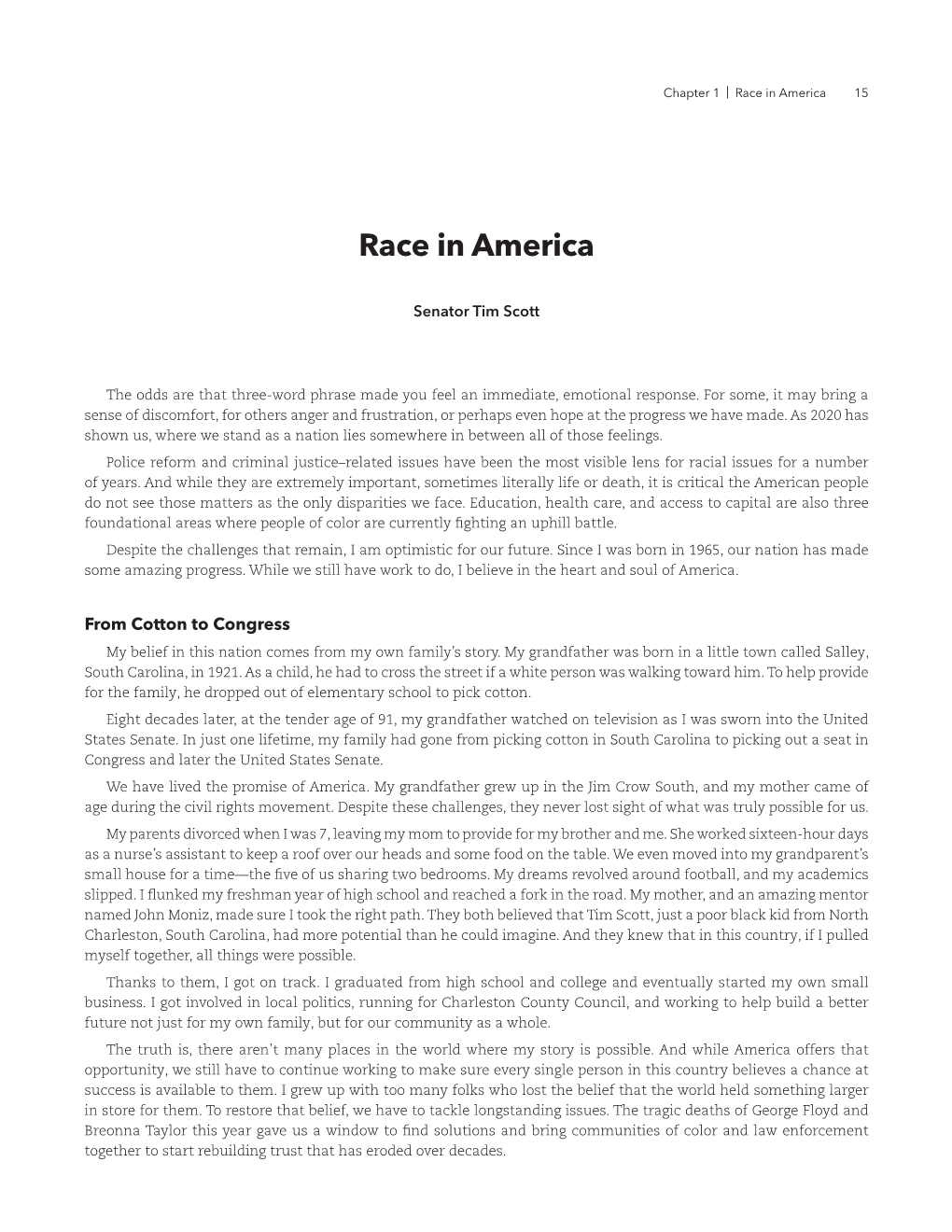

Race in America 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Committees 2021

Key Committees 2021 Senate Committee on Appropriations Visit: appropriations.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patrick J. Leahy, VT, Chairman Richard C. Shelby, AL, Ranking Member* Patty Murray, WA* Mitch McConnell, KY Dianne Feinstein, CA Susan M. Collins, ME Richard J. Durbin, IL* Lisa Murkowski, AK Jack Reed, RI* Lindsey Graham, SC* Jon Tester, MT Roy Blunt, MO* Jeanne Shaheen, NH* Jerry Moran, KS* Jeff Merkley, OR* John Hoeven, ND Christopher Coons, DE John Boozman, AR Brian Schatz, HI* Shelley Moore Capito, WV* Tammy Baldwin, WI* John Kennedy, LA* Christopher Murphy, CT* Cindy Hyde-Smith, MS* Joe Manchin, WV* Mike Braun, IN Chris Van Hollen, MD Bill Hagerty, TN Martin Heinrich, NM Marco Rubio, FL* * Indicates member of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, which funds IMLS - Final committee membership rosters may still be being set “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Visit: help.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patty Murray, WA, Chairman Richard Burr, NC, Ranking Member Bernie Sanders, VT Rand Paul, KY Robert P. Casey, Jr PA Susan Collins, ME Tammy Baldwin, WI Bill Cassidy, M.D. LA Christopher Murphy, CT Lisa Murkowski, AK Tim Kaine, VA Mike Braun, IN Margaret Wood Hassan, NH Roger Marshall, KS Tina Smith, MN Tim Scott, SC Jacky Rosen, NV Mitt Romney, UT Ben Ray Lujan, NM Tommy Tuberville, AL John Hickenlooper, CO Jerry Moran, KS “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Finance Visit: finance.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Ron Wyden, OR, Chairman Mike Crapo, ID, Ranking Member Debbie Stabenow, MI Chuck Grassley, IA Maria Cantwell, WA John Cornyn, TX Robert Menendez, NJ John Thune, SD Thomas R. -

Mcconnell Announces Senate Republican Committee Assignments for the 117Th Congress

For Immediate Release, Wednesday, February 3, 2021 Contacts: David Popp, Doug Andres Robert Steurer, Stephanie Penn McConnell Announces Senate Republican Committee Assignments for the 117th Congress Praises Senators Crapo and Tim Scott for their work on the Committee on Committees WASHINGTON, D.C. – Following the 50-50 power-sharing agreement finalized earlier today, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) announced the Senate Republican Conference Committee Assignments for the 117th Congress. Leader McConnell once again selected Senator Mike Crapo (R-ID) to chair the Senate Republicans’ Committee on Committees, the panel responsible for committee assignments for the 117th Congress. This is the ninth consecutive Congress in which Senate leadership has asked Crapo to lead this important task among Senate Republicans. Senator Tim Scott (R-SC) assisted in the committee selection process as he did in the previous three Congresses. “I want to thank Mike and Tim for their work. They have both earned the trust of our colleagues in the Republican Conference by effectively leading these important negotiations in years past and this year was no different. Their trust and experience was especially important as we enter a power-sharing agreement with Democrats and prepare for equal representation on committees,” McConnell said. “I am very grateful for their work.” “I appreciate Leader McConnell’s continued trust in having me lead the important work of the Committee on Committees,” said Senator Crapo. “Americans elected an evenly-split Senate, and working together to achieve policy solutions will be critical in continuing to advance meaningful legislation impacting all Americans. Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit our nation, our economy was the strongest it has ever been. -

Ranking Member John Barrasso

Senate Committee Musical Chairs August 15, 2018 Key Retiring Committee Seniority over Sitting Chair/Ranking Member Viewed as Seat Republicans Will Most Likely Retain Viewed as Potentially At Risk Republican Seat Viewed as Republican Seat at Risk Viewed as Seat Democrats Will Most Likely Retain Viewed as Potentially At Risk Democratic Seat Viewed as Democratic Seat at Risk Notes • The Senate Republican leader is not term-limited; Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY) will likely remain majority leader. The only member of Senate GOP leadership who is currently term-limited is Republican Whip John Cornyn (R-TX). • Republicans have term limits of six years as chairman and six years as ranking member. Republican members can only use seniority to bump sitting chairs/ranking members when the control of the Senate switches parties. • Committee leadership for the Senate Aging; Agriculture; Appropriations; Banking; Environment and Public Works (EPW); Health Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP); Indian Affairs; Intelligence; Rules; and Veterans Affairs Committees are unlikely to change. Notes • Current Armed Services Committee (SASC) Chairman John McCain (R-AZ) continues to receive treatment for brain cancer in Arizona. Senator James Inhofe (R-OK) has served as acting chairman and is likely to continue to do so in Senator McCain’s absence. If Republicans lose control of the Senate, Senator McCain would lose his top spot on the committee because he already has six years as ranking member. • In the unlikely scenario that Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA) does not take over the Finance Committee, Senator Mike Crapo (R-ID), who currently serves as Chairman of the Banking Committee, could take over the Finance Committee. -

CDIR-2014-02-18-SC-S-1.Pdf

234 Congressional Directory SOUTH CAROLINA SOUTH CAROLINA (Population 2010, 4,625,364) SENATORS LINDSEY GRAHAM, Republican, of Seneca, SC; born in Seneca, July 9, 1955; education: graduated, Daniel High School, Central, SC; B.A., University of South Carolina, 1977; awarded J.D., 1981; military service: joined the U.S. Air Force, 1982; Base Legal Office and Area Defense Counsel, Rhein Main Air Force Base, Germany, 1984; circuit trial counsel, U.S. Air Forces; Base Staff Judge Advocate, McEntire Air National Guard Base, SC, 1989–94; presently a Colonel, Air Force Reserves; award: Meritorious Service Medal for Outstanding Service; Meritorious Service Medal for Active Duty Tour in Europe; professional: established private law practice, 1988; former member, South Carolina House of Representatives; Assistant County Attorney for Oconee County, 1988–92; City Attorney for Central, SC, 1990–94; member: Walhalla Rotary; American Legion Post 120; appointed to the Judicial Arbitration Commission by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court; religion: attends Corinth Baptist Church; commit- tees: Appropriations; Armed Services; Budget; Judiciary; elected to the 104th Congress on November 8, 1994; reelected to each succeeding Congress; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 5, 2002, reelected to each succeeding Senate term. Office Listings http://lgraham.senate.gov 290 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................... (202) 224–5972 Chief of Staff.—Richard Perry. FAX: 224–3808 Legislative Director.—Mathew Rimkunas. Scheduler / Press Secretary.—Alice James. Deputy Communications Director.—Lorcan Connick. 130 South Main Street, Suite 700, Greenville, SC 29601 ........................................... (864) 250–1417 State Director.—Van Cato. Upstate Regional Director.—Laura Bauld. 530 Johnnie Dodds Boulevard, Suite 202, Mt. -

GUIDE to the 117Th CONGRESS

GUIDE TO THE 117th CONGRESS Table of Contents Health Professionals Serving in the 117th Congress ................................................................ 2 Congressional Schedule ......................................................................................................... 3 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) 2021 Federal Holidays ............................................. 4 Senate Balance of Power ....................................................................................................... 5 Senate Leadership ................................................................................................................. 6 Senate Committee Leadership ............................................................................................... 7 Senate Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................. 8 House Balance of Power ...................................................................................................... 11 House Committee Leadership .............................................................................................. 12 House Leadership ................................................................................................................ 13 House Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................ 14 Caucus Leadership and Membership .................................................................................... 18 New Members of the 117th -

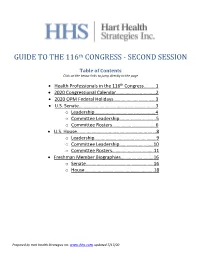

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

Graduate Students and the “PROSPER Act”

Graduate Students and the “PROSPER Act” The Higher Education Act (HEA), was originally created in 1965 to “strengthen the educational resources of our colleges and universities and to provide financial assistance for students in postsecondary and higher education” (Pub L. No. 89-329). This act governs federal higher education programs that affect affordability, accreditation, oversight, and federal regulations. This act is reauthorized every few years, most recently in 2008, and is currently due for reauthorization. On December 13th, 2017 the House Committee on Education and the Workforce approved HR 4508, the Promoting Real Opportunity, Success, and Prosperity through Education (PROSPER) Act, along party lines. The proposed legislation includes changes to federal financial aid for graduate students. In an attempt to improve and simplify student aid, it changes or eliminates many of the programs that graduate students use to finance their education. On behalf of current and future graduate students across the country, the Student Advocates for Graduate Education (SAGE) Coalition has serious concerns about the impacts of this proposal. HR 4508 eliminates the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) Program for future borrowers. PSLF is a program that many current and former graduate students rely on if planning for careers in public service. The professions that qualify for PSLF comprise an estimated 25 percent of the work force and often require a graduate degree including social work, education, public defense, librarianship, urban planning, and more.1 While these fields have alternative career paths in the private sector, many students seek comparatively lower-wage careers in the public sector. For example, the PSLF program has been used medical students to serve in public clinics in rural areas. -

Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress

Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION AND FORESTRY BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Pat Roberts, Kansas Debbie Stabenow, Michigan Mike Crapo, Idaho Sherrod Brown, Ohio Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont Richard Shelby, Alabama Jack Reed, Rhode Island Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Sherrod Brown, Ohio Bob Corker, Tennessee Bob Menendez, New Jersey John Boozman, Arkansas Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota Pat Toomey, Pennsylvania Jon Tester, Montana John Hoeven, North Dakota Michael Bennet, Colorado Dean Heller, Nevada Mark Warner, Virginia Joni Ernst, Iowa Kirsten Gillibrand, New York Tim Scott, South Carolina Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts Chuck Grassley, Iowa Joe Donnelly, Indiana Ben Sasse, Nebraska Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota John Thune, South Dakota Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota Tom Cotton, Arkansas Joe Donnelly, Indiana Steve Daines, Montana Bob Casey, Pennsylvania Mike Rounds, South Dakota Brian Schatz, Hawaii David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland Luther Strange, Alabama Thom Tillis, North Carolina Catherine Cortez Masto, Nevada APPROPRIATIONS John Kennedy, Louisiana REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC BUDGET Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Mitch McConnell, Patty Murray, Kentucky Washington Mike Enzi, Wyoming Bernie Sanders, Vermont Richard Shelby, Dianne Feinstein, Alabama California Chuck Grassley, Iowa Patty Murray, -

1 May 5, 2021 the Honorable Jack Reed the Honorable Jon Tester

WASHINGTON, DC 20510 May 5, 2021 The Honorable Jack Reed The Honorable Jon Tester Chairman Chairman Senate Armed Services Committee Senate Defense Appropriations Subcommittee 228 Russell Senate Office Building S-128, The Capitol Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 The Honorable James Inhofe The Honorable Richard Shelby Ranking Member Ranking Member Senate Armed Services Committee Senate Defense Appropriations Subcommittee 228 Russell Senate Office Building S-128, The Capitol Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Dear Chairmen and Ranking Members: As you consider the Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 defense authorization and appropriations bills, we strongly urge your continued support for the F-35 Lightning II program. We would urge the committee to support investments in relevance (modernization), readiness (sustainment) and rate (any service unfunded requirement). Today, the United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force, together with our allies, are flying more than 620+ aircraft operating from 27 locations around the world. The F-35 strengthens national security, enhances global partnerships, and powers economic growth. The program leverages economies of scale, both in production and sustainment, to drive down cost and increase efficiencies while improving interoperability with our partners around the world. As you know, near-peer adversaries like China and Russia continue to advance their air defense systems, develop their own 5th generation fighters, and invest heavily in emerging technologies that threaten America’s military edge. It is with this in mind that we urge the committee to ensure that a robust modernization plan is supported to continue to insert advanced technologies and capabilities into the F-35. This may require additional funds to restore previous funding reductions, address performance challenges tied to TR-3, and support critical capabilities tied to Block 4 modernization to keep the F-35 ahead of our adversaries. -

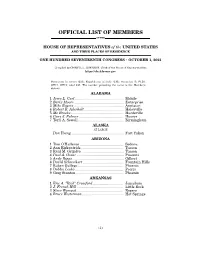

Official List of Members by State

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS • OCTOBER 1, 2021 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives https://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (220); Republicans in italic (212); vacancies (3) FL20, OH11, OH15; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Jerry L. Carl ................................................ Mobile 2 Barry Moore ................................................. Enterprise 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................. Phoenix 8 Debbie Lesko ............................................... -

Key Committees for the 116Th Congress

TH KEY COMMITTEES FOR THE 116 CONGRESS APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEES The Senate and House Appropriations Committees determine how federal funding for discretionary programs, such as the Older Americans Act (OAA) Nutrition Program, is allocated each fiscal year. The Subcommittees overseeing funding for OAA programs in both the Senate and the House are called the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies Subcommittees. Listed below, by rank, are the Members of Congress who sit on these Committees and Subcommittees. Senate Labor, Health & Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Subcommittee Republicans (10) Democrats (9) Member State Member State Roy Blunt, Chairman Missouri Patty Murray, Ranking Member Washington Richard Shelby Alabama Dick Durbin Illinois Lamar Alexander Tennessee Jack Reed Rhode Island Lindsey Graham South Carolina Jeanne Shaheen New Hampshire Jerry Moran Kansas Jeff Merkley Oregon Shelley Moore Capito West Virginia Brian Schatz Hawaii John Kennedy Louisiana Tammy Baldwin Wisconsin Cindy Hyde-Smith Mississippi Chris Murphy Connecticut Marco Rubio Florida Joe Manchin West Virginia James Lankford Oklahoma Senate Appropriations Committee Republicans (16) Democrats (15) Member State Member State Richard Shelby, Chairman Alabama Patrick Leahy, Ranking Member Vermont Mitch McConnell Kentucky Patty Murray Washington Lamar Alexander Tennessee Dianne Feinstein California Susan Collins Maine Dick Durbin Illinois Lisa Murkowski Alaska Jack Reed Rhode Island Lindsey Graham South Carolina -

Federal Disaster Response and Sba Implementation of the Rise Act

S. HRG. 114–636 FEDERAL DISASTER RESPONSE AND SBA IMPLEMENTATION OF THE RISE ACT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON SMALL BUSINESS AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 6, 2016 Printed for the Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–852 PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Sep 11 2014 12:33 May 15, 2017 Jkt 024852 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\24852.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON SMALL BUSINESS AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS DAVID VITTER, Louisiana, Chairman JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire, Ranking Member JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho MARIA CANTWELL, Washington MARCO RUBIO, Florida BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland RAND PAUL, Kentucky HEIDI HEITKAMP, North Dakota TIM SCOTT, South Carolina EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts DEB FISCHER, Nebraska CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey CORY GARDNER, Colorado CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware JONI ERNST, Iowa MAZIE K. HIRONO, Hawaii KELLY AYOTTE, New Hampshire GARY C. PETERS, Michigan MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming MEREDITH WEST, Republican Staff Director ROBERT DIZNOFF, Democratic Staff Director (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 12:33 May 15, 2017 Jkt 024852 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\24852.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER CONTENTS OPENING STATEMENTS Page Vitter, Hon. David, Chairman, and a U.S.