Kenya's Imperfect Fuel Market: Tackling Real Problems with Real Solutions*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maintenance Condition Monitoring

New trend in lubricants packaging P.20 Consumer choices lubricants survey P.18 WWW.LUBESAFRICA.COM VOL.4 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2012 NOT FOR SALE MAIN FEATURE Improving plant maintenance through condition monitoring A guide to oil analysis July-September 2012 | LUBEZINE MAGAZINE 1 PLUS: THE MARKET REPORT P.4 Inside Front Cover Full Page Ad 2 LUBEZINE MAGAZINE | July-September 2012 WWW.L UBE S A FR I C A .COM VOL 4 CONTENTS JULY—SEPTEMBER 2012 NEWS • INDUSTRY UPDATE • NEW PRODUCTS • TECHNOLOGY • COMMENTARY MAIN FEATURE 14 | OIL ANALYSIS — THE FUNDAMENTALS INSIDE REGULARS 7 | COUNTRY FEATURE 2 | Editor’s Desk Uganda lubricants market 4 | The Market Report — a brief overview Eac to remove preferential tariff treatment on MAIN FEATURE 10 | lubes produced within Lubrication and condition monitoring Eac block to improve plant availability Motorol Lubricants Open Shop 14 | MAIN FEATURE In Kenya Puma Energy plans buyout of Oil analysis — The Fundamentals KenolKobil 18 | ADVERTISER’S FEATURE Additives exempted from Consumer choices lubricants survey PVoC standards — GFK 6 | Questions from our readers 20 | PACKAGING FEATURE 28 | Last Word Engine oil performance in New trends in lubricants packaging 8 MAINTENANCE numbers 22 | TECHNOLOGY FEATURE FEATURE Oil degradation Turbochargers 26 | PROFILE and lubrication 28 10 questions for lubricants 24 professionals EQUIPMENT 27 | ADVERTISER’S FEATURE FEATURE Lubrication equipment The ultimate solution in sugar mill for a profitable and lubrication professional workshop July-September 2012 | LUBEZINE MAGAZINE 1 Turn to Turbochargers and lubrication P.8 New trend in lubricants packaging P.20 Consumer choices lubricants survey P.18 WWW.LUBESAFRICA.COM VOL.4 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2012 NOT FOR SALE EDITOR’SDESK VOL 3 • JANUARY-MARCH 2012 MAIN FEATURE Improving plant maintenance through EDITORIAL condition monitoring A guide to oil analysis One year and July-September 2012 | LUBEZINE MAGAZINE 1 PLUS: THE MARKET REPORT P.4 still counting! Publisher: Lubes Africa Ltd elcome to volume four of Lubezine magazine. -

Kenolkobil Limited Annual Report & Financial Statements

2010 KenolKobil Limited Annual Report & Financial Statements Vision ů To be the leading brand in all markets we operate in, and a major player in Africa. Mission ů To develop, improve and increase quality and total value of our products and services. ů To become a market leader through continuous innovation, customer focus and to provide the highest quality products and services. ů To maintain a highly motivated, well trained human resource base. ů To deliver the highest Shareholders’ values. 2 ANNUAL REPORT & FINANCIAL STATEMENTS - 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Directorate & Administration 4 Notice of the Annual General Meeting 5 Chairman & Group Managing Director’s Report 6 - 7 Board of Directors 8 Group Management Team 9 Corporate Governance 10 Corporate Social Responsibility 11 Financial Highlights 12 Director’s Report 14 Statement of the Directors’ Responsibilities 15 Report of the Independent Auditor 16 - 17 Consolidated Income Statement 18 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 19 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 20 Company Statement of Financial Position 21 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 22 Company Statement of Changes in Equity 23 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 24 Notes to the Financial Statements 25 - 70 Principal Shareholders and share distribution 71 ANNUAL REPORT & FINANCIAL STATEMENTS - 2010 DIRECTORATE & ADMINISTRATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS J I Segman Chairman and Group Managing Director C Field-Marsham Appointed on 28 September 2001 Resigned on 16 November 2010 D Oyatsi Appointed on 10 August -

World Investment Report 2011: Non-Equity Modes of International Production and Development

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT WORLD INVESTMENT REPORT 2011 NON-EQUITY MODES OF INTERNATIONAL PRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT WORLD INVESTMENT REPORT 2011 NON-EQUITY MODES OF INTERNATIONAL PRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT New York and Geneva, 2011 ii World Investment Report 2011: Non-Equity Modes of International Production and Development NOTE The Division on Investment and Enterprise of UNCTAD is a global centre of excellence, dealing with issues related to investment and enterprise development in the United Nations System. It builds on three and a half decades of experience and international expertise in research and policy analysis, intergovernmental consensus-building, and provides technical assistance to developing countries. The terms country/economy as used in this Report also refer, as appropriate, to territories or areas; the designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. In addition, the designations of country groups are intended solely for statistical or analytical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage of development reached by a particular country or area in the development process. The major country groupings used in this Report follow the classification of the United Nations Statistical Office. These are: Developed countries: the member countries of the OECD (other than Chile, Mexico, the Republic of Korea and Turkey), plus the new European Union member countries which are not OECD members (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta and Romania), plus Andorra, Bermuda, Liechtenstein, Monaco and San Marino. -

African Continental Free Trade Area: Advancing Pan-African Integration. Some Considerations

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT AFRICAN CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE AREA: Advancing Pan-African Integration Some Considerations UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT AFRICAN CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE AREA: Advancing Pan-African Integration Some Considerations New York and Geneva, 2016 Note The material contained in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted but acknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should be sent to the UNCTAD Secretariat, at: Palais de Nations, 1211, Geneva 10, Switzerland. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any position whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers and boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The views expressed in this publication reflect solely the views of the author. This is an unedited publication. Acknowledgements This study was prepared for UNCTAD by Mr. Osvaldo Agatiello under the framework of a Development Account Project 1213 AR on "Strengthening Capacities of African Countries in Boosting Intra-African Trade". It was supervised by Mr. Bonapas Onguglo, Senior Economic Affairs Officer, UNCTAD, and Mr. Ahmed Mutkhar, Economic Affairs Officer, UNCTAD. It was also reviewed by Mr. Joseph Kodzo Banini, consultant with UNCTAD. UNCTAD/WEB/DITC/2016/5 Copyright©United Nations, 2016 All rights reserved Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................... I INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 Challenges and Opportunities for African Continental Integration and Trade Development ......... -

The Acquisition of Kenolkobil Plc by Rubis Energie Sas

THE ACQUISITION OF KENOLKOBIL PLC BY RUBIS ENERGIE SAS. 1. The Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) approved the acquisition of KenolKobil Plc by Rubis Energie SAS. 2. Rubis Energie SAS (Rubis), the acquirer, is a subsidiary of Rubis SCA, an international firm that deals in the storage, distribution and sale of petroleum, liquefied petroleum gas, food and chemical products. 3. Rubis distributes petroleum products, liquid petroleum gas and bitumen across Europe, the Caribbean and Africa. Rubis does not directly or indirectly control any undertakings in Kenya and, therefore, does not have relevant turnover or assets within the country. 4. KenolKobil Plc (KenolKobil), the target, is incorporated in Kenya and is listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE). Rubis presently owns 24.99% of KenolKobil’s issued shares. 5. KenolKobil Plc is a holding company for KenolKobil Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Ethiopia and Burundi. These subsidiaries engage in the importation, storage, marketing and retail of petroleum products. 6. The proposed transaction, as per a public offer by Rubis, will result in Rubis making a cash offer of KES 23 per share for 1,182,968,076 shares, thereby taking 100% control of KenolKobil. 7. The proposed transaction qualified as a merger within the meaning of Section 2 and 41 of the Competition Act No.12 of 2010. The combined turnover of the parties is over Ksh. 1 Billon for the preceding year (2017) and, therefore, the transaction meets the threshold for full merger analysis as provided in the Merger Threshold Guidelines. 8. For purposes of analysing the proposed transaction, the Authority determined that the relevant product markets are: i. -

Zm-Government-Gazette-Dated-2020-09-11-No-6905.Pdf

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Price: KI 0.00 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 ®Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—.K350.00 No. 6905] Lusaka, Friday, 11th September, 2020 ÍVoLLVI No. 74 Gazette Notice No. 866 of 2020 [9620180 The Energy Regulation Act (Act No. 12 of 2019) Notice of intention to Issue Licenses Members of the General Public are hereby informed that the Energy Regulation Board intends to issue Licenses to the under-listed Applicants, fourteen days from the date of this notice in accordance with the provisions of the Energy Regulation Act No. 12 of 2019. Any one objecting to the issuance of any of such Licences whether on personae environmental or other grounds may do so by filing a written objection wi thin fourteen days of the publication of this notice as stipulated under section 33 of the Energy Regulation Act as read with the Energy Regulation (Licensing) Regulations 1998 Statutory Instrument No. 2 of 1998. The objector must provide their physical address and contact details. The written objection must be addressed to: L. H. Lungo (Ms), Director-General, P.O. Box 37631 Energy Regulation Board Lusaka INITIAL APPLICATIONS No. Applicant Address and Name of Shareholders Name of Directors/ Directors Type ofLicence Application Location /Sole Traders Sole Traders Interest in other Date Energy Undertakings i 2 . Amideast 397/A, off 1. Abbas Osseili 1. Abbas Osseili None Distribute, 16.06.2020 Enterprises Makeni Road, 2. Abdullah Osseili 2. Abdullah Osseili Import and Limited Makeni, Export Lusaka Petroleum Products (Valid for 5 years) 2. Onsite Fuel CV14 1. -

Oil & Gas Industry Overview

Africa: Oil & Gas Industry Overview November 2016 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 2. Industry Overview 3. Upstream 4. Midstream 5. Downstream 6. Recent Developments 7. Investor Section Disclaimer: This document is provided for information purposes only. The information is believed to be reliable, but TresVista does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. It should not be used, relied upon, or treated as a substitute for specific professional advice. Opinions, estimates, and assumptions constitute our judgment as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. Additional information is available upon request. Images used in this document are for reference only and may not be reproduced, copied, transmitted or manipulated in any way. © TresVista Financial Services 2013 1. Executive Summary TresVista Financial Services Executive Summary ▪ 650mn African homes do not have access to electricity limiting economic expansion and deterring outside investment interest Social ▪ Potential consumption is much greater than present with Africa containing 17.0% of the world’s population but only consuming 4.0% of it’s Oil & Gas ▪ Most large African economies are heavily reliant on oil & Gas exports Dependence on ▪ 70.0% of countries such as Nigeria’s government revenues are derived from Oil export, therefore small Oil & Gas changes in the price leads to large losses for the government ▪ Fragmented value chain, with more -

Change Management Strategy in Response to Environmental Challenges by Kenolkobil Limited

CHANGE MANAGEMENT STRATEGY IN RESPONSE TO ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES BY KENOLKOBIL LIMITED A Research Project Submitted In Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirement For The Award Of Master Of Business Administration Degree School Of Business University Of Nairobi NOVEMBER 2012 DECLARATION STUDENT’S DECLARATION I declare that this research project is my own original work. It is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the degree of Master of Business Administration, School of Business University of Nairobi. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in any other university. Date: Ojwang’ Thomas Odol Student No: D61/62974/2011 SUPERVISOR’S DECLARATION This project has been submitted for examination with my approval as university supervisor. Dr. Z. B. Awino, PhD. Senior Lecturer, Department of Business Administration School of Business University of Nairobi 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my profound and sincere gratitude to the following individuals: My supervisor, Dr. Z.B. Awino, PhD, for his support encouragement and guidance on this research project. I am exceptionally thankful for his assistance. I also owe this gratitude to my friends, Paul, Samson, Ann and Sarah for their constant support throughout this MBA program. Thank you for your support, your patience with me throughout and your understanding is appreciated. For all those lecturers at the University of Nairobi, all my friends and family, I take this opportunity to recognize you for your understanding and motivation. v 11 DEDICATION To my wife, Mercy Salim Odol and my children Amanda and Alvin whose support and tolerance, encouragement, patience and most of all love had given me the strength to persevere through all those stressful moments during these 18 months. -

Quarterly Statistical Bulletin

Quarterly Statistical Bulletin QUARTER ENDED JUNE 2012 Issue 12/2012 The CMA Capital Markets Bulletin – Q2/2012 The Capital Markets Authority Bulletin is developed and published by the Capital Markets Authority. While reasonable care has been taken to prepare this bulletin, the Authority accepts no responsibility or liability whatsoever, resulting from the use of information herein. The Capital Markets Authority has no objection to the material herein being used, provided an acknowledgement of the same is made. Any comments and/or suggestions on any of the features/sections may be sent to [email protected]. 1 The CMA Capital Markets Bulletin – Q2/2012 Abbreviations and Acronyms BR Brokers CDSC Central Depository and Settlement Corporation CDS Central Depository and Settlement CIC Co-operative Insurance Company CMA Capital Markets Authority CMC Cooper Motors Corporation CPI Consumer price index DTB Diamond Trust Bank EAC East African Community EAPCC East African Portland Cement EC East African Corporate investors EI East African Individuals FC Foreign Corporate Investors FI Foreign Investor IOSCO International Organization of Securities Commissions IPO Initial Public Offer KES Kenya Shillings LC Local Corporate LI Local Individuals NASI NSE All-Share Index NIC National Industrial Credit NSE Nairobi Securities Exchange PO Public Offer Q Quarter qoq quarter on quarter USD United States Dollars WB World Bank 2 The CMA Capital Markets Bulletin – Q2/2012 Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ......................................................................................................2 -

The Effect of Stock Split Announcements on Share Prices of Companies Listed at the Nairobi Securities Exchange

THE EFFECT OF STOCK SPLIT ANNOUNCEMENTS ON SHARE PRICES OF COMPANIES LISTED AT THE NAIROBI SECURITIES EXCHANGE By PITHON NDARU NYAGA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF COMMERCE (FINANCE AND ACCOUNTING) DEGREE IN THE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND PUBLIC MANAGEMENT AT KCA UNIVERSITY OCTOBER, 2017 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my original work and has not been previously published or submitted elsewhere for the award of a degree. I also declare that this contains no material written or published by other people except where due reference is made and the author duly acknowledged. Student Name: PITHON NDARU NYAGA Reg. No. 15/05784 Sign: Date: I do hereby confirm that I have examined the master’s dissertation of PITHON NDARU NYAGA And have certified that all revisions that the dissertation panel and examiners recommended have been adequately addressed. Sign: Date: DR. GEORGE KOSIMBEI Dissertation Supervisor THE EFFECT OF STOCK SPLIT ANNOUNCEMENTS ON SHARE PRICES OF COMPANIES LISTED AT THE NAIROBI SECURITIES EXCHANGE ABSTRACT Corporate announcements have many effects on the stock markets and this has made the study of stock price movements an area that has attracted a lot of attention from various researchers. All over the world, it is now a requirement from the capital market regulators that any publicly quoted company intending to make any corporate announcement must write to the respective stock exchanges where their shares are traded. This study contributes towards understanding the behaviour of share prices in relation to stock split announcements for companies listed at the Nairobi securities market in Kenya. -

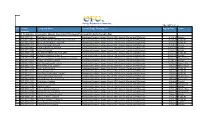

S/N Licence Number Company Name Licence Type Description Expiry

ERC/PET/LIC-3.1 S/N Licence Company Name Licence Type Description Expiry Date Town Number A. Companies Licensed for Import, Export and Wholesale Petroleum Products (Except LPG) 1 ERC/PET/3106 Gulf Energy Limited Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 28-Oct-17 Nairobi 2 ERC/PET/3107 FUTURES ENERGY COMPANY LIMITED Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 28-Oct-17 NAIROBI 3 ERC/PET/3113 BLUE SKY ENERGY LIMITED Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 28-Oct-17 NAIROBI 4 ERC/PET/3114 Heller Petroleum Limited Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 28-Oct-17 Garissa 5 ERC/PET/3122 GAPCO KENYA LIMITED Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 17-Nov-17 Nairobi 6 ERC/PET/3151 Lake Oil Limited Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 20-Nov-17 Nairobi 7 ERC/PET/3154 STABEX INTERNATIONAL LTD Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 30-Nov-17 NAIROBI 8 ERC/PET/3164 Ainushamsi Energy Limited Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 30-Nov-17 Nairobi 9 ERC/PET/3175 Bakri International Energy Company Limited Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 30-Nov-17 Head Office 10 ERC/PET/3181 Galana Oil Kenya Limited Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and Wholesale 19-Dec-17 Nairobi 11 ERC/PET/3192 East African Gasoil Limited Petroleum Business Licence (Except LPG)-Import, Export and -

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Price: K10.00 Net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—K350.00

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Price: K10.00 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—K350.00 No. 6935] Lusaka, Friday, 4th December, 2020 [Vol. LV, No. 105 Gazette Notice No. 1372 of 2020 ¡9948033 The Energy Regulation Act Chapter 436 of the Laws of Zambia Notice of Intention to Issue Licences Members of the General Public are hereby informed that the Energy Regulation Board (ERB) intends to issue Licences to the under listed Applicants, fourteen (14) days from the date of this notice in accordance with the provisions of the Energy Regulation Act No. 12 of 2019. Any one objecting to the issuance of any of such Licences whether on personal, environmental or other grounds may do so by filing a written objection within fourteen (14) days of the publication of this notice as stipulated under Section 10 of the Energy Regulation Act as read with the Energy Regulation (Licensing) Regulations 1998 Statutory Instrument No. 2 of 1998. The objector must provide their physical address and contact details. The written objection must be addressed to: L. H. Lungu (Ms.), P.O. Box 37631 Director General, Lusaka Energy Regulations Board INITIAL APPLICATIONS ID Applicant Address and Name of Name of Directors/ Directors Type of Application Date Location Shareholders/ sole Traders Interest in Licence Sole Traders other Energy Undertakings 1. Access Energy Plot No. 3745 1. Larisa Reddy 1. Larisa Reddy None Manufacture, 02.09.2020 Solutions Suite No. 17b, (South African) (South African) Supply, Limited Olympia, Lusaka 2. Varsha Reddy 2. Varsha Reddy Installation and (South African) (South African) Maintenance of Renewable Energy Generating Equipment (Valid for 5 years) 3.