Wells, Logan 03-20-2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1St Robe Ledwash 600S on JLS | 1

1st Robe LEDWash 600s on JLS | 1 10 December 2010 Courtesy Louise Stickland The very first batch of the new Robe ROBIN LEDWash 600 LED Wash fixtures off the production line in the Czech Republic were delivered to leading UK lighting rental company HSL, with 40 of them going straight out on JLS’s UK arena tour, specified by lighting designer Dave Lee. JLS are the UK’s favourite boyband, their meteoric career kicking off after being runners up on the 2008 X-Factor talent show. Since then they have sold 1.3 million albums worldwide – including their new and second studio release “Outta This World” – and have enjoyed massive chart success inclosing several Number 1s as well as winning 2010 Brit Awards for “Best Breakthrough Artist” and “Best British Single” for ‘Beat Again’. The show for this, their second major tour, has been created by artistic director Beth Honan with a set and stage design by Peter Barnes, with all the technical production co-ordinated by Production North, overseen on the road by production manager Karen Ringland. 1st Robe LEDWash 600s on JLS | 2 When Dave Lee was choosing his fixtures, he specifically needed some very bright and lightweight units to do certain jobs. When HSL’s project manager Mike Oates demonstrated the LEDWash 600 to him – he knew this was the ideal fixture. The first challenge he needed to overcome with the LEDWashes was to illuminate a large catwalk approximately 120 ft long that flies in from the roof and hangs above the audience for a whole section of the show, allowing the band to get close up and personal to their hoards of adoring fans. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2011 T 02

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2011 T 02 Stand: 16. Februar 2011 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2011 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT02_2011-3 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie Katalogisierung, Regeln für Musikalien und Musikton-trä- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ger (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ -

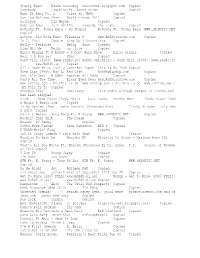

End of Year Charts: 2010

End Of Year Charts: 2010 Chart Page(s) Top 200 Singles .. .. .. .. .. 2 - 5 Top 200 Albums .. .. .. .. .. 6 - 9 Top 200 Compilation Albums .. .. .. 10 - 13 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site or forum, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Published by: UKChartsPlus e-mail: [email protected] http://www.UKChartsPlus.co.uk - 1 - Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 2010 7” Vinyl only Download only Entry Date 2010 2009 2008 2007 Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) (w/e) High Wks 1 -- -- -- LOVE THE WAY YOU LIE - Eminem featuring Rihanna Interscope (2748233) 03/07/2010 2 28 2 -- -- -- WHEN WE COLLIDE - Matt Cardle Syco (88697837092) 25/12/2010 13 3 3 -- -- -- JUST THE WAY YOU ARE (AMAZING) - Bruno Mars Elektra ( USAT21001269) 02/10/2010 12 15 4 -- -- -- ONLY GIRL (IN THE WORLD) - Rihanna Def Jam (2755511) 06/11/2010 12 10 5 -- -- -- OMG - Usher featuring will.i.am LaFace ( USLF20900103) 03/04/2010 1 41 6 -- -- -- FIREFLIES - Owl City Island ( USUM70916628) 16/01/2010 13 51 7 -- -- -- AIRPLANES - B.o.B featuring Hayley Williams Atlantic (AT0353CD) 12/06/2010 1 31 8 -- -- -- CALIFORNIA GURLS - Katy Perry featuring Snoop Dogg Virgin (VSCDT2013) 03/07/2010 12 28 WE NO SPEAK AMERICANO - Yolanda Be Cool vs D Cup 9 -- -- -- 17/07/2010 1 26 All Around The World/Universal -

Wavelength (June 1983)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 6-1983 Wavelength (June 1983) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (June 1983) 32 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/32 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPING THE NEW LEADERSHIP IN NEW ORLEANS MUSIC A Symposium on New Orlea Music Business Sponsored by the University of New Orleans Music Department and the Division of Continuing Education and wavelength Magazine. Moderator John Berthelot, UNO Continuing Education Coordinator/Instructor in the non-credit music business program. PROGRAM SCHEDULE How To Get A Job In A New Orleans Music Club 2 p.m.-panel discussion on the New Orleans club scene. Panelists include: Sonny Schneidau, Talent Manager. Tipitina's, John Parsons, owner and booking manager, Maple Leaf Bar. personal manager of • James Booker. one of the prcx:lucers of the new recording by James Booker. Classified. Jason Patterson. music manager of the Snug Harbor. associate prcx:lucer/consultant for the Faubourg Jazz Club, prcx:lucer for the first public showing of One Mo· Time, active with ABBA. foundation and concerts in the Park. Toulouse Theatre and legal proceedings to allow street music in the French Quarter. Steve Monistere, independent booking and co-owner of First Take Studio. -

Bridget Kelly Band (Marketing/Bio/Links/Reviews): 1

Bridget Kelly Band (Marketing/Bio/Links/Reviews): 1. Bridget Kelly Band... featuring the Sultry & Soulful vocals of Bridget Kelly and the incendiary guitar wizardry of Tim Fik 2. Genre: Electric Blues/Contemporary Blues/ Blues-Rock 3. Country of Origin: USA / Region: Florida (North Central)-- National Touring Act (Road Dawg Management) Bridget Kelly Band: Formed 2012 - present 4. Location/Cities of residence: Gainesville, Florida 5. Tagline: "Rockin' Electric Blues" Overview and Highlights: * Celebrating the release of their 6th Album/CD "Dark Spaces" (2020), on Alpha Sun Records, the Bridget Kelly Band keeps rolling along, with 13 brand new original tunes that run the gamut from Blues-Rock to Southern Rock in this radio friendly and much-anticipated release. #3 on the RMR Blues-Rock chart July, 2020 * BKB's last album "Blues Warrior" was a Top-10 charting CD, reaching #3 on the RMR "Blues Rock" album chart in July of 2018. Blues Warrior was the #12 Blues-Rock album for 2018. * BKB's 2017 Album "Bone Rattler" was #1 for 24 weeks on the RMR Electric Blues Chart! Bridget Kelly Band... * Award winning artists, BKB are 2-time IBC Semi-Finalists in Memphis (2015, 2016) * Tim Fik-- 2018 Blues Foundation "Keeping the Blues Alive" Award recipient (www.blues.org) * All Original Music tracks as heard on Sirius-XM radio, Pandora, Jango, Spotify, and syndicated Blues radio shows around the world. The Bridget Kelly Band members (2018-2019)... Bridget Kelly - Vocals; Tim Fik - Guitar, Vocals; Greg Mullins, Mark Armbrecht - Bass; Alex Klausner and Tim -

November 2014

2014 November Links Volume 6, Issue 7 Vincent’s Thanksgiving Sense In this issue, we start with a spotlight on Things to Do in Nice: Food, Glorious Food by Megan. Next we turn to the lessons learned from Silent to Talkies: The Evolution of VADs by Pamela Combs and Teamwork: Achieving True Collaboration in the Care of Pediatric VAD Patients by Monica Horn, followed by Lessons Learned by Erin Wells. Did you know there is a link with Victor Hugo and La Villa Nice Victor Hugo to his famous novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame made into a silent film in 1923 starring Lon Chaney (The Man of a Thousand Faces)? From this success, Universal and Lon Chaney proceeded with another great silent film from another French author, Gaston Leroux’s famous Phantom of the Opera. In 1925, the innovation of Technicolor was in its infancy with only shades of red seen in this silent film with the Masque of the Red Death scene. Next, it’s Angela Logan with Treatment of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Lung Transplant: Fifty Shades of Gray and Updates from the Pathology Council, with a Focus on AMR by Brandon Larsen. Afterwards, is the Giving Thanks by Rita Price, Fearbola by Sultana Peffley, Nicole Brooks, Marilyn Galindo and Vincent Valentine, Dedication, Deification and Divination of Voltaire: An Apotheosis as well as Dedication and Thanksgiving by Vincent Valentine. There are Special Interest Pieces and Megan Barrett announces the ISHLT 2015 Preliminary Program Released. Finally, we give a warm ISHLT congratulations to Lut Berben on the birth of her twins. -

Hartman Cards Music/Entertainment Catalog

William B. Cornell AMV Sales & Consultation LLC 5439 Leeway Dallas TX 75236 Ph: 800-283-1146/972-283-1128 Fax: 972-283-5547 [email protected] www.amvsales.com Hartman Cards Music/Entertainment Catalog April 2012 Following is a distillation of catalogs and catalog pages from Hartman Cards focusing on their music and entertainment related products. Hartman Cards have no minimum order To view the entire selection of products offered by Hartman Cards go to: http://www.hartmancards.com/ Contact me if any questions or if you wish to order… Will Cornell PDF processed with CutePDF evaluation edition www.CutePDF.com BOOK CATALOGUE FLAME TREE PUBLISHING 2011–2012 PDF processed with CutePDF evaluation edition www.CutePDF.com 1 NEW TITLE: POPULAR CULTURE RELEASE DATE: JANUARY 2012 Rihanna: Bad Girl by Michael Heatley is one of the first in an exciting series of unofficial biographies celebrating some of the most popular and influential celebrities – stars who are constantly talked about and whose every new release, life event or opinion is awaited with baited breath by legions of fans. In the Top Ten on YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, with millions of followers, Rihanna is adored by a huge online community. Princess RiRi has soared to the heights of stardom, every year rocking a hot new look as she works the audience with sizzling style and awesome sounds. She breaks records left, right and centre, with 20 million album sales under her belt and the youngest artist in the Billboard chart’s history to achieve 10 number-one singles. If you love RiRi then you gotta get Rihanna: Bad Girl – the ultimate celebration of this girl’s talent, beauty and wow-factor, with brilliant pics and inspirational words – a must-have for all fans. -

Vincent's Seasonal Sense

All newsletters are on the ISHLT website at: www.ishlt.org/publications/ishltLinksNewsletter.asp. In thIs Issue A Focus on Heart Failure and Transplant Medicine ISHLT Vincent’s seasonal sense 1 The Tenwek Phenomenon 27 Tom Klein, BS, CCO, LCP, FPP Links in the spotlight: 2 Mouth-Watering Montreal! 2013 isHlT Academy: 28 MR/s XYZ at isHlT 2013 core competencies in December 2013 Tereza Martinu, MD Mechanical circulatory Volume 4, Issue 8 support Donor Management 4 Jeffrey Teuteberg, Research Update: Growing Daniel Goldstein, Andreas VincenT’s seAsonAl sense links Between Donor Zuckermann, David Feldman Management and Transplant and Salpy Pamboukian communities This month we have many symphonies coming together in harmony David P Nelson, MD From The Ashes … 29 to bring us a December to remember. Just over 200 years ago, Charles Darrin Malinoski, MD The Rise of the Heart Failure Google Group Dickens was born. He brought forth among others, Ebenezer Scrooge The changing landscape 6 David A Baran, MD in Heart Donors’ epidemiology who needed retuning from the past and present spirits to alter his Luciano Potena, MD, PhD Donor Management 30 future. His heart changed no different than the growing heart of Steven S L Tsui, MD, FRCS Task Force Metrics Laurent Sebbag David P Nelson, MD the Grinch by three sizes when he recognized the true meaning organ shortage: What 9 The Problems And Pitfalls 31 of Christmas in Whoville. It was in December when Ludwig van europeans Do About it of Recruitment: Part ii Beethoven was born who went against convention and provided a Jacqueline M Smits, MD, PhD Roger W Evans, PhD different structure and style of music coming from his heart. -

Starry Eyed Ellie Goulding Discodust.Blogspot.Com Copied

StarryEyed EllieGoulding discodust.blogspot.com Copied Somebody Lomaticcft.SunnyBrown Copied BustItBabyPt.2 Pliesft.NeYo Copied CanYouBelieve Akon May'sFinest2011 Copied Lollipop LilWayne Copied NabiunNabi ZainBhikha TowardsTheLight Copied KYoungFt.YoungBergGoStupid KYoungFt.YoungBerg WWW.iM1MUSIC.NET Copied Action FloRidaFeat.PleasureP www.RnBXclusive.com Copied IsItYou? Cassie StepUp2Soundtrack Copied NellyParadise Nelly Suit Copied RideWitMe Nelly notitle Copied MarioWinansftPDiddyIDontWanaKnow mariowinans Copied Hell4AHustler 2Pac Copied SexyGirl(2008)[www.RnB4U.in] BobbyValentinoSexyGirl(2008)[www.RnB4U.in ] www.RnB4U.in Copied AllIHaveftLLCoolJ Jenniferlopez ThisIsMeThen Copied ThemLips(Feat.RayL) RedCafe HotNewHipHop.com Copied SayIt'sOver NDubz AgainstAllOdds Copied PartyAllTheTime BlackEyedPeas www.RnBXclusive.com Copied www.FnrTop.com|BY.ThisIs50 www.FnrTop.com|BY.ThisIs50 www.FnrTop.com| BY.ThisIs50 Copied Changes 2Pac Duplicate ThismediaalreadyexistsiniTunesand hasbeenskipped. HindiThodaPyaarThodaMagicLazyLamhe AnushaMani ThodaPyaarThod [email protected] Copied InMySystem(feat.JodieConnor)(ExtendedMix) TinchyStryder JulyJam z2010 Copied Smith&Wesson YungBergFt.KYoung WWW.iM1MUSIC.NET Copied Rockin'ThatShit TheDream Copied Heaven DJSammy Copied GottaMoveFaster SeanKingston MIX8 Copied K'NAANWavin'Flag Copied JLSFtTinieTempahEyesWideShut Copied MundianToBachKe ManjabiMC MinistryOfSoundMaximumBassCD1 Copied That'sAllSheWroteFt.Eminem(ProducedByDr.Luke) T.I. SoundsofNovemb er2010 Copied ILuvIt YoungJeezy Copied I'mGone JaySean Copied -

16.11.12 £5.15

MW Cover - rhianna - 16.11.12_cover template 10/11/2012 12:43 Page 1 16.11.12 £5.15 Project1_Layout 1 09/11/2012 17:23 Page 1 CoverV2_cover template 13/11/2012 17:32 Page 1 46 9776669776136 THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC www.musicweek.com 16.11.12 £5.15 BIG INTERVIEW ANALYSIS MEDIA 13 20 24 4AD’s Simon Halliday on the Radio 1 won’t play One of commercial radio’s most iconic indie label’s recent Robbie Williams – successful programmers, Andy Roberts, success and its future has it got a case? on the changing shape of broadcast ELEVEN TAKEOVERS HAVE COST MAJORS £3.8BN IN TWO DECADES – BUT HAVE THEY BEEN WORTH IT? To buy or not to buy LABELS concentrates on deals for closed or amalgamated with Similar fates awaited the one of the US market’s most I BY PAUL WILLIAMS individual labels rather than one another record company. artists and operations of famed successful labels with a roster major group completely buying Around half the total outlay label names such as A&M, including Eminem and Lady s a reported 90-plus out a rival major, such as covered Bertelsmann buying a Chrysalis, Geffen and London Gaga, and Island Records, parties eye up a wealth of Universal’s $1.9bn (£1.2bn) 75% stake in Zomba in 2002, Records (although several have consistently the most successful AEMI assets, a Music Week A&R source for UK repertoire. study today highlights the Island led the Official UK potential business perils of singles and artist albums charts buying iconic labels. -

Bridget Kelly Band (Marketing/Bio/Links/Reviews): 1

Bridget Kelly Band (Marketing/Bio/Links/Reviews): 1. Bridget Kelly Band... featuring the Sultry & Soulful vocals of Bridget Kelly and the incendiary guitar wizardry of Tim Fik 2. Genre: Electric Blues/Contemporary Blues/ Blues-Rock 3. Country of Origin: USA / Region: Florida (North Central) 4. Location/Cities of residence: Gainesville / Lake City, Florida 5. Tagline: "Rockin' High-Energy Electric Blues" 6. Overview... Celebrating the release of their 5th Top-10 charting CD: "Blues Warrior"-- the Bridget Kelly Band... continues to Rock the Blues. * #1 RMR Electric Blues Album * Two-time IBC Semi-Finalists (2015, 2016) and Award winning Blues artists, * Tim Fik--2018 Blues foundation "Keeping the Blues Alive" Award recipient * Original Music as heard on Sirius-XM radio, Pandora, Jango, Spotify, and syndicated Blues radio shows around the world. The Bridget Kelly Band is... Bridget Kelly - Vocals; Tim Fik - Guitar, Vocals; Mark Armbrecht - Bass; and Tim Mulberry - Drums 7. Social media Handles/Links (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, etc.) Facebook-- BKBblues https://www.facebook.com/BKBblues/ Instagram-- bridgetkellyband Twitter-- @BKBblues Band Website: www.bridgetkellyband.com http://www.bridgetkellyband.com/ Links to Bridget Kelly Band music from the "Bone Rattler" CD AirPlayDirect Link to Bridget Kelly Band "Bone Rattler" CD (2017) http://www.airplaydirect.com/music/bridgetkellybandbonerattler/ CD Baby link to Bone Rattler (2017): https://store.cdbaby.com/cd/bridgetkellyband4 Sound Cloud Links to selected tracks from the Bridget Kelly Band -

In-Depth Analysis of Exclusive Official Charts Company Data SINGLES

Q1-REPORT_1-16_News and Playlists 18/05/2012 10:55 Page 1 Q1 2012 In-depth analysis of exclusive Official Charts Company data SINGLES • ALBUMS • CATALOGUE • COMPILATIONS • MAJORS • INDEPENDENTS • DISTRIBUTION Q1-REPORT_1-16_News and Playlists 18/05/2012 10:21 Page 2 02 Q1 2012 www.musicweek.com ALL CHARTS, GRAPHS AND DATA IN THIS REPORT ARE COPYRIGHT OF THE OFFICIAL CHARTS COMPANY All analysis in this report is the copyright of Intent Music Week, Intent Media, 1st Floor, Suncourt House, 18-26 Essex Road, London N1 8LR Media, and all charts, graphs Tel 020 7226 7246 and data in this report are Q1/2012 Web www.musicweek.com / www.intentmedia.co.uk copyright of the Official Head of Business Analysis / Music Week editor Charts Company. Any Extensive report compiler Tim Ingham Paul Williams Publisher republication of this analysis from Design and layout Dave Roberts information is strictly Ed Miller Managing director forbidden. All rights Music Week, Nikki Thompson Stuart Dinsey are reserved. based on Official Charts CONTENTS Company data elcome to Music Week’s first extensive quarterly report into the UK recorded music market, brought to you in W association with the Official Charts Company. The aim of this three-monthly report is to look statistically at the market in an in-depth way that is impossible to achieve over a few pages. Alongside analysing the headline figures, what you have here crunches further and deeper with a detailed look at what occurred in the past quarter by sector, genre, format and by the individual performances of record groups and distributors.