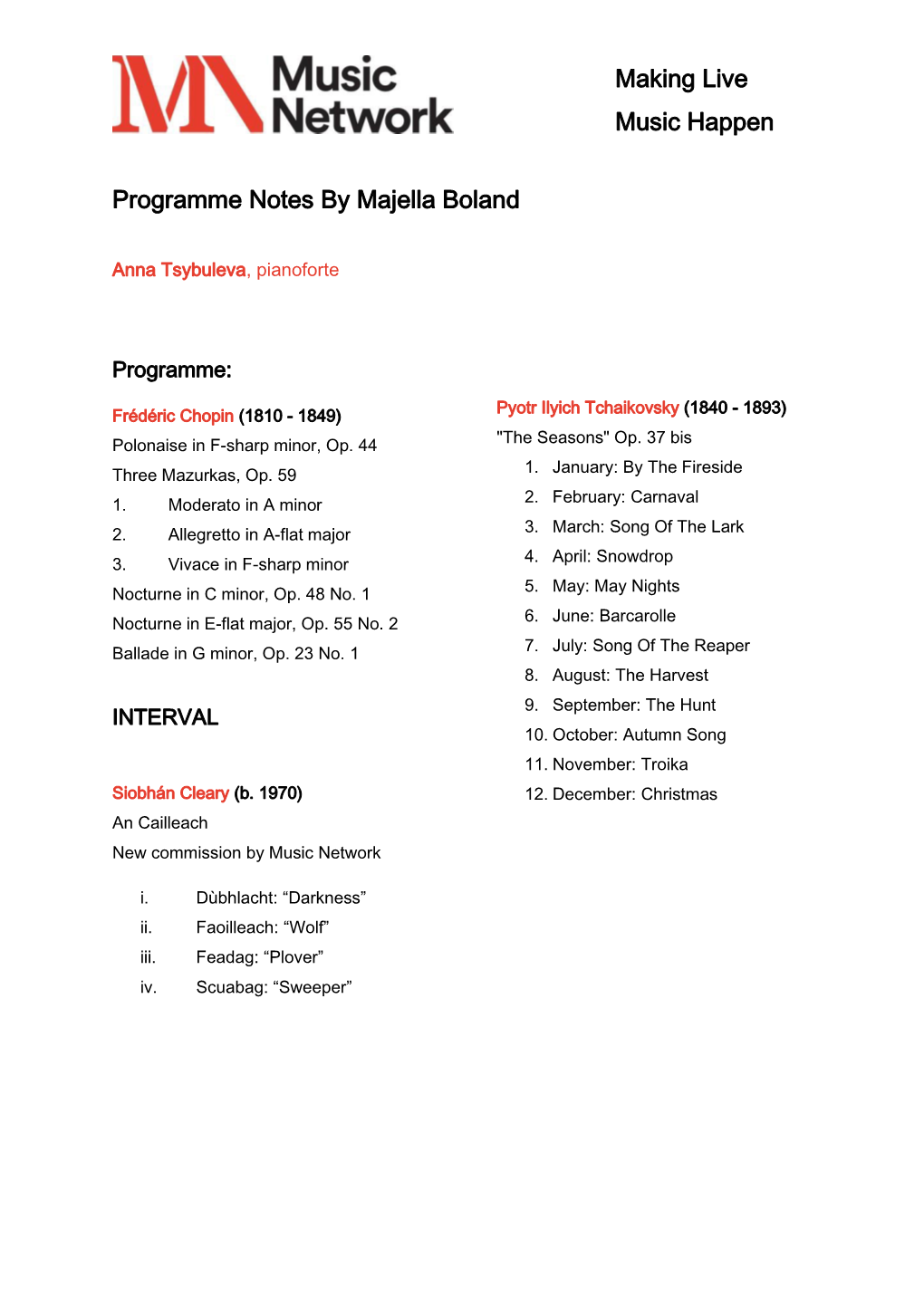

Making Live Music Happen Programme Notes by Majella Boland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op

Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op. 39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Stavrianou, Eleni Persefoni Citation Stavrianou, Eleni Persefoni. (2021). Adapting Piano Music for Ballet: Tchaikovsky's Children's Album, Op. 39 (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 04:39:03 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/660266 ADAPTING PIANO MUSIC FOR BALLET: TCHAIKOVSKY’S CHILDREN’S ALBUM, OP. 39 by Eleni Persefoni Stavrianou ____________________________________ Copyright © Eleni Persefoni Stavrianou 2021 A DMA Critical Essay Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2021 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Creative Project and Lecture-Recital Committee, we certify that we have read the Critical Essay prepared by: titled: and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Critical Essay requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ submission of the final copies of the essay to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this Critical Essay prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Critical Essay requirement. -

Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky

APRIL 2020 RACHMANINOFF AND TCHAIKOVSKY APRIL 17 – 19, 2020 MASTERWORKS #7: Two Russian composers, teacher and pupil, both legends in the world of classical music and revered by their countrymen, shared something else in common: periods of severe and crippling depression. Dr. Richard Kogan, a Juilliard-trained pianist, lonely 14-year old into despair.x He mourned the loss graduate of Harvard College and Medical School, of his mother for the rest of his life and called it the and a Clinical Professor of Psychology on the faculty most “crucial event” he’d ever experienced.xi With of the Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City, his mother’s death, a young Tchaikovsky became has concluded that a disproportionate number of the parent figure for his younger twin brothers, the great composers of classical music suffered from Anatoly and Modest.xii Despite the family’s wish that mental illness.i In his years as a student, Dr. Kogan Tchaikovsky have a career in the Ministry of Justice, pursued both music and pre-medical studies. His the young man was drawn to music. When the St. roommate at Harvard was famed cellist Yo-Yo Ma, Petersburg Conservatory opened its doors in 1862, and, with violinist Lynn Chang, they performed as a Tchaikovsky was among its first students.xiii From that trio.ii With a choice between music and medicine, point forward, his musical path was clear, and his Dr. Kogan chose medicine, but, in so doing, noted work as a composer earned him a teaching position the close relationship between the two fields.iii In at the Moscow Conservatory. -

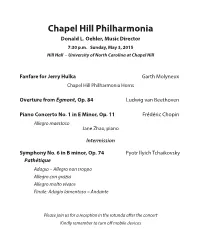

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

String Orchestra of Brooklyn Repertoire Updated February 28, 2011

String Orchestra of Brooklyn Repertoire Updated February 28, 2011 Anton Arensky Variations on a Theme by Tchaikovsky Johann Sebastian Bach Art of the Fugue, selections Piano Concerto No. 1 in d minor, BWV 1052 Piano Concerto No. 5 in f minor, BWV 1056 Erbarme Dich from St. Matthew's Passion Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 Samuel Barber Dover Beach for Baritone and Strings Adagio for Strings Bela Bartok Divertimento for Strings Roumanian Folk Dances Ludwig van Beethoven Egmont Overture* Grosse Fuge (arr. Furtwängler) Violin Concerto, Op. 61* Johannes Brahms Variations on a Theme by Haydn* Kenji Bunch Nocturne Tony Conrad Eleven Across John Corigliano Voyage for String Orchestra Claude Debussy Sacred and Profane Dances Antonin Dvorak Symphony No. 8* Josh Feltman Triptych Osvaldo Golijov Muertes des Angel Antonio Carlos Gomes Sonata for Strings Judd Greenstein Four on the Floor Edvard Grieg Holberg Suite Nathan Hall Last Rose Georg Frederic Handel Concerto Grosso Op. 6, No. 3 in D Major Ian Hartsough Stick Figures Bernard Herrmann Suite from Psycho Paul Hindemith Acht Stücke, Op. 43/3 Trauermusik for viola and strings Leos Janacek Suite for Strings Gabriel Lubell Quomodo sedet sola Gustav Mahler Adagietto from Symphony No. 5 Matt McBane 2 x 4 for String Octet Felix Mendelssohn Octet for Strings String Symphony No. 10 Symphony No. 1* Alex Mincek Ebb and Flow Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Adagio and Fugue, k546 Requiem Mass, k626* Serenata Notturna, k239 Sinfonia Concertante, k364* sull'aria from Le Nozze di Figaro* Symphony No. 40, k550* Arvo Pärt Fratres, version for String Orchestra and Percussion Krzysztof Penderecki Ciaconna (“Polish Requiem”) Josh Penman Lovesongs to God, second movement Tristan Perich I am not without my eyes open Duane Pitre Suspended in Dreams Claudio Santoro Mini Concerto for String Orchestra Franz Schubert Death and the Maiden, second movement (arr. -

R O B E R T O a L a G

C ROBERTO ALAGNA CARUSO 1873 1873 Lucio Dalla 1943–2012 Anton Rubinstein 1829–1894 Helen Rhodes Francesco Cilea 1866–1950 1 CARUSO 5:15 7 Ô LUMIÈRE DU JOUR 4:04 (aka Guy d’Hardelot) 1858–1936 18 NO, PIÙ NOBILE 2:52 Text: Lucio Dalla from Néron (Act II – Néron) 13 PARCE QUE (BECAUSE) 2:34 from Adriana Lecouvreur (Act IV – Maurizio) Libretto: Jules Barbier Text: Helen Rhodes Libretto: Arturo Colautti Gioachino Rossini 1792–1868 Arr.: Enrico Caruso 2 DOMINE DEUS 5:17 Teodoro Cottrau 1827–1879 Giuseppe Verdi 1813–1901 from Petite Messe solennelle 8 SANTA LUCIA 4:13 14 QUAL VOLUTTÀ TRAS CORRERE 4:18 Jules Massenet Text: Teodoro Cottrau from I Lombardi alla prima crociata 19 CHIUDO GLI OCCHI 2:51 George Frideric Handel 1685–1759 (Act III – Oronte, Giselda, Pagano) from Manon 3 FRONDI TENERE … Giacomo Puccini 1858–1924 Libretto: Temistocle Solera (Act II – Des Grieux, sung in Italian) OMBRA MAI FU 3:57 9 VECCHIA ZIMARRA 2:29 Libretto: Henri Meilhac & Philippe Gille from Serse HWV 40 (Act I – Serse) from La bohème (Act IV – Colline) Emanuele Nutile 1862–1932 Italian translation: Angelo Zanardini Libretto: Nicolò Minato Libretto: Giuseppe Giacosa & Luigi Illica 15 MAMMA MIA CHE VO’ SAPÉ? 3:37 1873 Text: Ferdinando Russo VINTAGE BONUS Antônio Carlos Gomes 1836–1896 Antônio Carlos Gomes C ARUSO Ernesto De Curtis 1875–1937 4 MIA PICCIRELLA 3:46 10 SENTO UNA FORZA Georges Bizet 1838–1875 20 TU CA NUN CHIAGNE 2:25 from Salvator Rosa (Act I – Gennariello) INDOMITA 4:52 16 MI PAR D’UDIR ANCORA 3:23 Text: Libero Bovio Libretto: Antonio Ghislanzoni from Il Guarany (Act I – Pery & Cecilia) from Les Pêcheurs de perles Libretto: Antonio Scalvini & Carlo d’Ormeville (Act I – Nadir, sung in Italian) ROBERTO ALAGNA tenor attr. -

The Cause of P. I. Tchaikovsky's (1840 – 1893) Death: Cholera

Esej Acta med-hist Adriat 2010;8(1);145-172 Essay UDK: 78.071.1 Čajkovski, P. I. 616-092:78.071.1 Čajkovski, P. I. THE CAUSE OF P. I. TCHAIKOVSKY’S (1840 – 1893) DEATH: CHOLERA, SUICIDE, OR BOTH? UZROK SMRTI P. I. ČAJKOVSKOG (1840.–1893.): KOLERA, SAMOUBOJSTVO ILI OBOJE? Pavle Kornhauser* SUMMARY The death of P. I. Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893) excites imagination even today. According to the »official scenario«, Tchaikovsky had suffered from abdominal colic before being infected with cholera. On 2 November 1893, he drank a glass of unboiled water. A few hours later, he had diarrhoea and started vomiting. The following day anuria occured. He lost conscious- ness and died on 6 November (or on 25 Oktober according to the Russian Julian calendar). Soon after composer's death, rumors of forced suicide began to circulate. Based on the opin- ion of the musicologist Alexandra Orlova, the main reason for the composer's tragic fate lies in his homosexual inclination. The author of this article, after examining various sources and arguments, concludes that P. I. Tchaikovsky died of cholera. Key words: History of medicine 19th century, pathografy, cause of death, musicians, P. I. Tchaikovsky, Russia. prologue In symphonic music, the composer’s premonition of death is presented in a most emotive manner in the Black Mass by W. A. Mozart and G. Verdi (which may be expected taking into account the text: Requiem aeternum dona eis …), in the introduction to R. Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde and in the last movement of G. Mahler’s Ninth Symphony. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 7 May 2017 7pm Barbican Hall SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY NO 15 Mussorgsky arr Rimsky-Korsakov Prelude to ‘Khovanshchina’ Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto INTERVAL London’s Symphony Orchestra Shostakovich Symphony No 15 Sir Mark Elder conductor Anne-Sophie Mutter violin Concert finishes approx 9.10pm Generously supported by Celia & Edward Atkin CBE 2 Welcome 7 May 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO concert at BMW LSO OPEN AIR CLASSICS 2017 the Barbican, where we are joined by Sir Mark Elder for an all-Russian programme of works by Mussorgsky, The London Symphony Orchestra, in partnership with Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich. BMW and conducted by Valery Gergiev, performs an all-Rachmaninov programme in London’s Trafalgar The concert opens with the prelude to Mussorgsky’s Square on Sunday 21 May, the sixth concert in the opera Khovanshchina, in an arrangement by fellow Orchestra’s annual BMW LSO Open Air Classics Russian composer, Rimsky-Korsakov. Then we are series, free and open to all. delighted to see Anne-Sophie Mutter return as the soloist in Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, before lso.co.uk/openair Sir Mark Elder concludes the programme with Shostakovich’s final symphony, No 15. LSO WIND ENSEMBLE ON LSO LIVE I hope you enjoy the performance. I would like to take this opportunity to welcome Celia and The new recording of Mozart’s Serenade No 10 Edward Atkin, and to thank them for their generous for Wind Instruments (‘Gran Partita’) by the LSO support of this evening’s concert. -

FY19 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2018–19 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 6 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 20 Our Patrons On the cover: Yannick Nézet-Séguin takes a bow after his first official performance as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director PHOTO: JONATHAN TICHLER / MET OPERA 2 Introduction The 2018–19 season was a historic one for the Metropolitan Opera. Not only did the company present more than 200 exiting performances, but we also welcomed Yannick Nézet-Séguin as the Met’s new Jeanette Lerman- Neubauer Music Director. Maestro Nézet-Séguin is only the third conductor to hold the title of Music Director since the company’s founding in 1883. I am also happy to report that the 2018–19 season marked the fifth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so, as we recorded a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Saint-Saëns’s epic Samson et Dalila and also included three other new productions, as well as three exhilarating full cycles of Wagner’s Ring and a full slate of 18 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 13th season, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office, media, and presentations) totaled $121 million. As in past seasons, total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. The new productions in the 2018–19 season were the work of three distinguished directors, two having had previous successes at the Met and one making his company debut. -

Summary Provides an Overview of the Most Frequently Performed Composers and Works, and of U.S., Canadian, and Contemporary Composers and Works

The data below was compiled from the 2012-13 classical season repertoire submitted by 57 League of American Orchestras member orchestras. This summary provides an overview of the most frequently performed composers and works, and of U.S., Canadian, and contemporary composers and works. DATA SET TOTAL DATA COLLECTED FOR THE STATISTICS THAT FOLLOW 893 Concert performances 2929 Performances of individual works 57 Orchestras 933 Distinct compositions 301 Different composers Most frequently performed composers Scheduled Performances Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 230 Ludwig van Beethoven 198 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky 162 Johannes Brahms 145 Felix Mendelssohn 76 Franz Schubert 63 Maurice Ravel 62 Igor Stravinsky 58 Richard Wagner 55 Sergei Rachmaninoff 55 Aaron Copland 52 Franz Joseph Haydn 52 Antonin Dvorak 51 Richard Strauss 50 Claude Debussy 49 Jean Sibelius 49 Dmitri Shostakovich 42 Modest Mussorgsky 42 Johann Sebastian Bach 40 George Frederic Handel 39 Robert Schumann 38 Leonard Bernstein 35 Gustav Mahler 34 Sergei Prokofiev 33 George Gershwin 30 2 Most frequently performed works Scheduled Performances Modest Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition 23 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto in D major, Opus 35 23 Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Opus 98 20 Igor Stravinsky The Rite of Spring 20 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Opus 23 19 Igor Stravinsky The Firebird (all versions) 18 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Opus 36 18 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 17 Franz Schubert Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D. 759 "Unfinished" 17 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. -

Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Music director and conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin September 25, 2018 7:30 pm Photo: Jan Regan 2018/2019 SEASON Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN MUSIC DIRECTOR AND CONDUCTOR LISA BATIASHVILI VIOLIN Tuesday, September 25, 2018, at 7:30 pm Hancher Auditorium, The University of Iowa Liar, Suite from Marnie Nico Muhly (b. 1981) Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) I. Allegro moderato—Moderato assai II. Canzonetta: Andante III. Allegro vivacissimo INTERMISSION Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) I. Non allegro II. Andante con moto (Tempo di valse) III. Lento assai—Allegro vivace—Lento assai, come prima—L’istesso tempo, ma agitato— Poco meno mosso—“Alliluya” 3 Photo: Jessica Griffin Jessica Photo: EVENT SPONSORS MACE AND KAY BRAVERMAN GRADUATE IOWA CITY GARY AND RANDI LEVITZ WILLIAM MATTHES AND ALICIA BROWN-MATTHES LAMONT D. AND VICKI J. OLSON MARY LOU PETERS JACK AND NONA ROE CANDACE WIEBENER HANCHER'S 2018/2019 SEASON IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF DICK AND MARY JO STANLEY 4 Photo: Jessica Griffin Jessica Photo: BUILDING COMMUNITY June 30, 2018–January 6, 2019 Stanley Visual Classroom Iowa Memorial Union Côte d’Ivoire; Baule peoples Asie usu (nature spirit) pair Wood 15” H The Stanley Collection, X1986.527 Individuals with disabilities are encouraged to attend all University of Iowa-sponsored events. If you are a person with a disability who requires a reasonable accommodation in order to participate in this program, please contact the SMA in advance at 319-335-1727. -

Operas Performed in New York City in 2013 (Compiled by Mark Schubin)

Operas Performed in New York City in 2013 (compiled by Mark Schubin) What is not included in this list: There are three obvious categories: anything not performed in 2013, anything not within the confines of New York City, and anything not involving singing. Empire Opera was supposed to perform Montemezzi’s L'amore dei tre re in November; it was postponed to January, so it’s not on the list. Similarly, even though Bard, Caramoor, and Peak Performances provide bus service from midtown Manhattan to their operas, even though the New York City press treats the excellent but four-hours-away-by-car Glimmerglass Festival like a local company, and even though it’s faster to get from midtown Manhattan to some performances on Long Island or in New Jersey or Westchester than to, say, Queens College, those out-of-city productions are not included on the main list (just for reference, I put Bard, Caramoor, and Peak Performances in an appendix). And, although the Parterre Box New York Opera Calendar (which includes some non-opera events) listed A Rite, a music-theatrical dance piece performed at the BAM Opera House, I didn’t because no performer in it sang. I did not include anything that wasn’t a local in-person performance. The cinema transmissions from the Met, Covent Garden, La Scala, etc., are not included (nor is the movie Metallica: Through the Never, which Owen Gleiberman in Entertainment Weekly called a “grand 3-D opera”). I did not include anything that wasn’t open to the public, so the Met’s workshop of Scott Wheeler’s The Sorrows of Frederick is not on the list.