“Fifty Years After Cisneros V. Ccisd: a History of Racism, Segregation, and Continued Inequality for Minority Students”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S9886

S9886 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE September 21, 2006 States to offer instate tuition to these prehensive solution to the problem of communities where it is very tough to students. It is a State decision. Each illegal immigration must include the succeed, they turn their backs on State decides. It would simply return DREAM Act. crime, drugs, and all the temptations to States the authority to make that The last point I make is this: We are out there and are graduating at the top decision. asked regularly here to expand some- of their class, they come to me and It is not just the right thing to do, it thing called an H–1B visa. An H–1B visa say: Senator, I want to be an Amer- is a good thing for America. It will is a special visa given to foreigners to ican; I want to have a chance to make allow a generation of immigrant stu- come to the United States to work be- this a better country. This is my home. dents with great potential and ambi- cause we understand that in many They ask me: When are you going to tion to contribute fully to America. businesses and many places where peo- pass the DREAM Act? I come back here According to the Census Bureau, the ple work—hospitals and schools and and think: What have I done lately to average college graduate earns $1 mil- the like—there are specialties which help these young people? lion more in her or his lifetime than we need more of. -

Southside Area Development Plan (October 29, 2019)

City of Corpus Christi AreaSouthside Development Plan DRAFT OCTOBER 29, 2019 Southside ACKNOWLEDEGMENTS Sheldon Schroeder CITY COUNCIL Commission Member Joe McComb Michael M. Miller Mayor Commission Member Rudy Garza Jr. Daniel M. Dibble Council Member At-Large Commission Member Paulette M. Guajardo Michael York Council Member At-Large Commission Member Michael T. Hunter Benjamin Polak Council Member At-Large Navy Representative Everett Roy Council Member District 1 Ben Molina STUDENT ADVISORY Council Member District 2 Roland Barrera COMMITTEE Council Member District 3 Ben Bueno Greg Smith Harold T. Branch Academy Council Member District 4 Estevan Gonzalez Gil Hernandez London High School Council Member District 5 Grace Hartridge Veterans Memorial High School Sara Humpal PLANNING COMMISSION London High School Carl E. Crull Ciara Martinez Chairman Richard King High School Jeremy Baugh Katie Ngwyen Vice Chairman Collegiate High School Marsha Williams Damian Olvera Commission Member Texas A&M Corpus Christi Heidi Hovda Natasha Perez Commission Member Del Mar College Kamran Zarghouni Emily Salazar Commission Member Mary Carroll High School Casandra Lorentson ADVISORY COMMITTEE Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee Alex Azali Wayne Lundquist Dorsal Development London Area Landowner Charles Benavidez Moses Mostaghasi Texas Department of Transportation Coastal Bend Homebuilders Association Donna Byrom Juan Pimentel London Resident Nueces County Public Works Daniel Carrizales Benjamin Polak Corpus Christi Metropolitan Planning Naval Air Station -

Powerful Partnership Practices 2009

Forward Texas Association of Partners in Education would like to express our gratitude to each district and organization who participated in the first edition of “Soaring to New Heights in Education: Powerful Partnerships Across Texas”. Through each of these programs, you have extended a helping hand to numerous Texas youth, and have exemplified the innovative partnerships, that are sure to be emulated across the state. On behalf of the TAPE Board of Directors, members, students and recipients of this publication, TAPE would also like to thank Applied Materials for supporting this publication through a grant. I know it is not recognition you seek, but this is a deed we will not allow to go unrecognized– education and academic excellence is and will continue to be a team effort. This grant provides an invaluable opportunity for TAPE to share best practices, so again we thank everyone for participating in the 2009 “Powerful Partnerships Across Texas” Sincerely, Allison Murray TAPE President Texas Association of Partners in Education 1 Introduction It is always exciting to learn about innovative partnerships being developed by Texas Association of Partners in Education (TAPE) members. With the ever changing needs of today’s youth and shifting economy TAPE recognizes that community engagement and innovation are key for the success of all students. Partnerships are, and will continue to be, critical to ensure students receive the resources necessary for success. Through thirty years of promoting partnerships TAPE has facilitated the sharing of partnership stories through our statewide and regional events. After hearing these incredible stories for so many years and hearing from our members how much they have learned from these stories, we have begun to compile them into one resource. -

Flour Bluff Independent School District Check Register October 2013 233916 Elite Printer Services Inc 10/11/2013 (610.00) 233937

FLOUR BLUFF INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT CHECK REGISTER OCTOBER 2013 CHECK CHECK NUMBER VENDOR DATE AMOUNT GENERAL FUND 233916 ELITE PRINTER SERVICES INC 10/11/2013 (610.00) 233937 LANDMARK PRINT FINISHING LLC 10/11/2013 (195.32) 233996 BARGANSKI, LINDA 10/3/2013 112.27 233997 CANNON, CHERYL 10/3/2013 38.54 233998 DIAL, STACY 10/3/2013 17.85 233999 SOLIS, ARMANDO 10/3/2013 5,411.60 234000 VALDEZ, GINA 10/3/2013 37.06 234001 ADF ENTERPRISES INC 10/4/2013 362.50 234002 ADVANCE EMS LTD 10/4/2013 400.00 234003 APUSEN, PRUDENCIO 10/4/2013 50.00 234004 BATES, JAMES 10/4/2013 88.74 234005 BELETIC, STEPHAN 10/4/2013 8.32 234006 BENAVIDES, OSCAR 10/4/2013 76.01 234007 BLUE BELL CREAMERIES LP 10/4/2013 453.15 234008 BOOK SYSTEMS INC 10/4/2013 125.00 234009 CALALLEN HIGH SCHOOL 10/4/2013 93.00 234010 CANTU, ROBERT 10/4/2013 115.20 234011 CLEAR LAKE HIGH SCHOOL 10/4/2013 250.00 234012 COASTAL BEND PEST CONTROL ASSOCIATION 10/4/2013 95.00 234013 COMMUNITIES IN SCHOOLS 10/4/2013 2,291.67 234014 COPELAND, HEATHER 10/4/2013 120.00 234015 CORPUS CHRISTI ISD 10/4/2013 967.00 234015 CORPUS CHRISTI ISD 10/11/2013 (967.00) 234016 EDUCATION SERVICE CENTER REGION I 10/4/2013 1,962.45 234017 GARCIA, DEBRA 10/4/2013 108.19 234018 GODOY, RICHARD 10/4/2013 146.00 234019 GONZALES, ROY 10/4/2013 369.93 234020 GREEN, ART 10/4/2013 129.74 234021 GREGORY PORTLAND HIGH SCHOOL 10/4/2013 200.00 234022 GUERRA, JOHNNY 10/4/2013 50.00 234023 HERNANDEZ, CARLA 10/4/2013 50.00 234024 HERTZ EQUIPMENT RENTAL CORPORATION 10/4/2013 1,398.07 234025 JOHNSON, REGINALD 10/4/2013 80.00 -

Congressional Record—Senate S9781

September 20, 2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S9781 or admission as a lawful permanent resident Drive hunts are run by fishers who Hispanic lawyer. Not one to be discour- on another basis under the INA. use scare tactics to herd, chase, and aged, James DeAnda joined another Subparagraph (F): provides for the removal corral the animals into shallow waters Hispanic lawyer to form a legal prac- from the United States, of any alien subject where they are trapped and then killed tice dedicated to representing Hispanic to the five-year limitation if the alien vio- lates the provisions of this paragraph, or if or hauled off live to be sold into cap- Americans. the alien is found to be removable or inad- tivity. The overexploitation of these In one of his earliest cases, James missible under applicable provisions of the highly social and intelligent animals DeAnda was a member of the four-per- INA. for decades has resulted in the serious son legal team behind Hernandez v. Subparagraph (G): provides the Attorney decline, and in some cases, the com- Texas, 1954, the first case tried by General with the authority to grant a waiver mercial extinction, of these species. Mexican American attorneys before the of the five-year limitation in certain ex- On April 7, 2005, I introduced Senate U.S. Supreme Court. In Hernandez, the traordinary situations where the Attorney Resolution 99 to help end this inhu- Supreme Court overturned the murder General finds that the alien would suffer ex- ceptional and extremely unusual hardship mane and unnecessary practice and conviction of a Hispanic man by an all- were such conditions not waived. -

Scholarships Awarded Since 5-09-2018

D Scholarships Awarded Since 5-09-2018 Grant Date Scholarship Term Award Last Name First Name County High School Attending College Attending Notes 6/6/2018 Bean-Dirks Memorial Scholarship - George West Fall $ 1,000.00 Gallagher Taylor Jim Wells George West High School 6/6/2018 Bean-Dirks Memorial Scholarship - George West Fall $ 1,000.00 Hyde Catherine Live Oak George West High School 6/6/2018 Bean-Dirks Memorial Scholarship - George West Fall $ 1,000.00 Pawlik Alyson Live Oak George West High School 6/6/2018 Bean-Dirks Memorial Scholarship - George West Fall $ 1,000.00 Wasicek Julia Live Oak George West High School 6/6/2018 Bean-Dirks Memorial Scholarship - George West Fall $ 1,000.00 Wills Sahara Live Oak George West High School 6/6/2018 Cletis Dulin Memorial Scholarship Fall $ 1,000.00 Upton Franklin Refugio Refugio High School 6/6/2018 London PTO Scholarship Fall $ 1,000.00 Burkholder Hannah Nueces London ISD 6/6/2018 London PTO Scholarship Fall $ 1,000.00 Igwe Christabel Nueces London ISD 6/6/2018 Martha Mahany Memorial Athletic Scholarship 1 year $ 1,000.00 Johnson Jessica Nueces Calallen High School 6/6/2018 NCJLS-Homemaking Scholarship 4 years $ 3,500.00 Chisum Green Nueces Tuloso Midway High School 2020 high school graduate 6/6/2018 NCJLS-Homemaking Scholarship 4 years $ 2,500.00 Madeleine Gulding Nueces Homeschool 2020 high school graduate 6/6/2018 Nueces County Junior Livestock Show Scholarship 4 years $ 3,000.00 Brimhall Kaycee Nueces Calallen High School 6/6/2018 Nueces County Junior Livestock Show Scholarship 4 years $ 3,000.00 -

BUZZ IS BACK YOUR SUPPORT IS VITAL to BUILDING a CHAMPIONSHIP MEN’S BASKETBALL PROGRAM at TEXAS A&M 12Th Man Foundation 1922 Fund

SPRING 2019 VOLUME 24, NO. 2 FUNDING SCHOLARSHIPS, PROGRAMS AND FACILITIES 12thManIN SUPPORT OF CHAMPIONSHIP ATHLETICS BUZZ IS BACK YOUR SUPPORT IS VITAL TO BUILDING A CHAMPIONSHIP MEN’S BASKETBALL PROGRAM AT TEXAS A&M 12th Man Foundation 1922 Fund The 1922 Fund provides a perpetual impact on the education of Texas A&M’s student-athletes. Our goal is to fully endow scholarships for every student-athlete, building a sustainable model of funding where your investment can provide the opportunity for Aggie student-athletes to excel in competition and in the classroom. Without generous families like the Moncriefs, I wouldn’t be able to be in the position I’m in at A&M. I truly appreciate their donations to the 1922 Fund and the time they invest in me. – COLTON PRATER ’20 Football Offensive Lineman 1922 Fund Donor Benefits $25,000 $50,000 $100,000 $250,000 $500,000+ Annual endowment report Recognition on 12th Man Foundation website One-time recognition in 12th Man Magazine A plaque for donor’s home and recognition in 12th Man Foundation offices Recognition on field of supported program during a game* Champions Council membership for a five year term Assignment of a specific student-athlete’s scholarship A donor spotlight article in 12th Man Magazine 12th Man Foundation will discuss recognition opportunities *Option exists for donor to choose their recognition at Kyle Field if desired Contact the Major Gifts Staff at 979-260-7595 For More Information About the 1922 Fund 6 11 22 Buzz Williams | Page 16 Texas A&M’s new head coach is instilling his relentless work ethic into the men’s basketball program BY CHAREAN WILLIAMS ’86 29 12TH MAN FOUNDATION IMPACTFUL DONORS STUDENT-ATHLETES 5 Foundation Update 22 Mark Welsh III & Mark Welsh IV ’01 14 Riley Sartain ’19 BY SAMANTHA ATCHLEY ’17 1922 Fund Student-Athlete 6 Champions Council Weekend BY MATT SIMON ’98 29 Shannon ’18 & David Riggs ’99 11 E.B. -

Flour Bluff Independent School District Check Register January 31, 2015

FLOUR BLUFF INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT CHECK REGISTER JANUARY 31, 2015 CHECK CHECK NUMBER VENDOR DATE AMOUNT GENERAL FUND 239014 CHICK-FIL-A 1/19/2015 (200.00) 239225 UNIFIRST HOLDINGS INC 1/19/2015 (604.62) 239310 EDUCATION SERVICE CENTER, REGION 2 1/5/2015 (80.00) 239599 PEREZ, JESSE JR 1/9/2015 (95.00) 239776 CULLIGAN OF CORPUS CHRISTI 1/5/2015 385.40 239777 EAN HOLDINGS LLC 1/5/2015 456.36 239778 JD PALATINE, LLC 1/5/2015 59.85 239779 SIGNS TODAY INC 1/5/2015 32.50 239780 SUSSER PETROLEUM COMPANY LLC 1/5/2015 14,904.35 239781 TIME WARNER CABLE 1/5/2015 6,526.04 239782 SAM'S CLUB DIRECT 1/6/2015 155.00 239783 WALMART COMMUNITY 1/6/2015 963.29 239784 WELLS FARGO 1/6/2015 4,258.00 239784 WELLS FARGO 1/6/2015 - 239784 WELLS FARGO 1/6/2015 - 239784 WELLS FARGO 1/6/2015 - 239785 LOPEZ, HECTOR 1/6/2015 4,126.30 239786 BLUE BELL CREAMERIES LP 1/8/2015 184.29 239787 COCA-COLA REFRESHMENTS USA 1/8/2015 1,720.08 239788 CORPUS CHRISTI PRODUCE CO INC 1/8/2015 2,008.32 239789 FLEETPRIDE 1/8/2015 2,597.28 239790 FLOWERS BAKING CO OF SAN ANTONIO LLC 1/8/2015 412.71 239791 GULF COAST PAPER CO INC 1/8/2015 79.46 239792 LABATT FOOD SERVICE 1/8/2015 19,125.93 239793 MILK PRODUCTS LLC (AUSTIN) 1/8/2015 7,517.36 239794 O'REILLY AUTOMOTIVE STORES INC 1/8/2015 1,524.83 239794 O'REILLY AUTOMOTIVE STORES INC 1/8/2015 - 239795 SAFEGUARD UNIVERSAL 1/8/2015 468.00 239796 SYSCO CENTRAL TEXAS INC 1/8/2015 4,867.04 239797 UNIFIRST HOLDINGS INC 1/8/2015 983.44 239798 ATZENHOFFER, DENA 1/8/2015 125.00 239799 BAILEY, RANDY 1/8/2015 70.00 239800 CARTER, CLINT 1/8/2015 -

Draft Southside Area Development Plan

City of Corpus Christi AreaSouthside Development Plan DRAFT JANUARY 14, 2020 Southside ACKN OWLEDEGMEN TS Sheldon Schroeder CITY COUNCIL Commission Member Joe McComb Michael M. Miller Mayor Commission Member Rudy Garza Jr. Daniel M. Dibble Council Member At-Large Commission Member Paulette M. Guajardo Michael York Council Member At-Large Commission Member Michael T. Hunter Benjamin Polak Council Member At-Large Navy Representative Everett Roy Council Member District 1 Ben Molina STUDENT ADVISORY Council Member District 2 Roland Barrera COMMITTEE Council Member District 3 Ben Bueno Greg Smith Harold T. Branch Academy Council Member District 4 Estevan Gonzalez Gil Hernandez London High School Council Member District 5 Grace Hartridge Veterans Memorial High School Sara Humpal PLANNING COMMISSION London High School Carl E. Crull Ciara Martinez Chairman Richard King High School Jeremy Baugh Katie Ngwyen Vice Chairman Collegiate High School Marsha Williams Damian Olvera Commission Member Texas A&M Corpus Christi Heidi Hovda Natasha Perez Commission Member Del Mar College Kamran Zarghouni Emily Salazar Commission Member Mary Carroll High School Jay Reining ADVISORY COMMITTEE Oso Creek I-Plan Coordination Committee Charles Benavidez Kara Rivas Texas Department of Transportation Young Business Professionals of the Coastal Donna Byrom Bend London Resident Gordon Robinson Marco Castillo Corpus Christi Regional Transit Authority Southside Resident Eloy Salazar Brent Chesney United Corpus Christi Chamber of Commerce Nueces County Commissioners Court, Steve Synovitz Precinct 4 Oso Creek I-Plan Coordination Committee Joseph Cortez John Tamez Corpus Christi Association of Realtors London Area Landowner Carl Crull Judi Whitis Planning Commission London ISD Rabbi Ilan Emanuel Corpus Christi Clergy Alliance Dr. -

Mexican Americans and the Politics of Racial Classification in the Federal Judicial Bureaucracy, Twenty-Five Years After Hernandez V

UCLA Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review Title Some are Born White, Some Achieve Whiteness, and Some Have Whiteness Thrust upon Them: Mexican Americans and the Politics of Racial Classification in the Federal Judicial Bureaucracy, Twenty-Five Years after Hernandez v. Texas Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4c7529jh Journal Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review, 25(1) ISSN 1061-8899 Author Wilson, Steven Harmon Publication Date 2005 DOI 10.5070/C7251021160 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SOME ARE BORN WHITE, SOME ACHIEVE WHITENESS, AND SOME HAVE WHITENESS THRUST UPON THEM: MEXICAN AMERICANS AND THE POLITICS OF RACIAL CLASSIFICATION IN THE FEDERAL JUDICIAL BUREAUCRACY, TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AFTER HERNANDEZ V. TEXAS STEVEN HARMON WILSON, PH.D.* This paper examines the problem of the racial and ethnic classification of Mexican Americans, and later, Hispanics, in terms of both self- and official identification, during the quarter- century after Hernandez v. Texas. The Hernandez case was the landmark 1954 decision in which the U.S. Supreme Court con- demned the "systematic exclusion of persons of Mexican de- scent" from state jury pools.1 Instead of reviewing the judicial rulings in civil rights cases, what follows focuses on efforts by federal judges in the Southern District of Texas to justify their jury selection practices to administrators charged with monitor- ing the application of various equal protection rules coming into force in the late 1970s. This topic arises from two curious coincidences. First, in the spring of 1979, James DeAnda - who had helped prepare the Hernandez case, and who was plaintiffs' attorney in another landmark to be described below, Cisneros v. -

Flour Bluff Independent School District Check Register March 31, 2014

FLOUR BLUFF INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT CHECK REGISTER MARCH 31, 2014 CHECK CHECK NUMBER VENDOR DATE AMOUNT GENERAL FUND 235737 HOUSTON INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT 3/6/2014 (255.00) 235874 INSIGHT INVESTMENTS CORP 3/3/2014 (2,900.00) 236073 APPLE INC 3/3/2014 275.00 236074 AUDIO VISUAL AIDS CORP 3/3/2014 1,697.00 236075 BARGANSKI, LINDA 3/3/2014 7.41 236076 BEST BUY BUSINESS ADVANTAGE ACCOUNT 3/3/2014 74.69 236077 BILL'S SPARKLING CITY CHARTER INC 3/3/2014 1,300.00 236078 BLUE BELL CREAMERIES LP 3/3/2014 590.13 236079 CARQUEST AUTO PARTS STORES 3/3/2014 88.00 236080 COASTAL DELI INC 3/3/2014 544.00 236081 COCA-COLA REFRESHMENTS USA 3/3/2014 1,380.96 236082 CORPUS CHRISTI PRODUCE CO INC 3/3/2014 3,473.59 236083 CORPUS CHRISTI FREIGHTLINER 3/3/2014 973.29 236084 DV SUBWAY LP 3/3/2014 345.00 236085 DWD PIZZA INC 3/3/2014 79.90 236086 EAN HOLDINGS LLC 3/3/2014 215.00 236087 EDUCATION SERVICE CENTER, REGION 2 3/3/2014 2,585.00 236088 EKON-O-PAC INC 3/3/2014 35.50 236089 FERGUSON ENTERPRISES INC 3/3/2014 7.31 236090 FISHER, ALAN PHD 3/3/2014 700.00 236091 FLEETPRIDE 3/3/2014 1,607.44 236092 FLOWERS BAKING CO OF SAN ANTONIO LLC 3/3/2014 567.81 236093 GRAHAM, KEVIN 3/3/2014 250.00 236094 GRIPCASE LLC 3/3/2014 46.84 236095 HARBOR PLAYHOUSE CO INC 3/3/2014 340.00 236096 INSCO DISTRIBUTING 3/3/2014 1,918.00 236097 JOHNSON CONTROLS INC 3/3/2014 1,348.75 236098 KELLYCO 3/3/2014 157.95 236099 LABATT FOOD SERVICE 3/3/2014 23,192.37 236100 LEARNING ZONE 3/3/2014 211.54 236101 LIVE WIRE MEDIA 3/3/2014 366.07 236102 LORENZ CORPORATION 3/3/2014 2,401.16 -

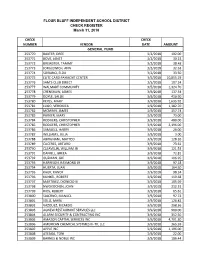

2018.03 CK Register.Xlsx

FLOUR BLUFF INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT CHECK REGISTER March 31, 2018 CHECK CHECK NUMBER VENDOR DATE AMOUNT GENERAL FUND 253770 BAXTER, DREE 3/2/2018 192.00 253771 BOVE, JANET 3/2/2018 30.23 253772 BREWSTER, TAMMY 3/2/2018 38.48 253773 JORGLEWICH, ANN 3/2/2018 32.63 253774 SORIANO, ELDA 3/2/2018 33.50 253775 ELITE CARD PAYMENT CENTER 3/5/2018 10,855.19 253776 SAM'S CLUB DIRECT 3/5/2018 107.24 253777 WALMART COMMUNITY 3/5/2018 1,324.70 253778 CRENSHAW, JAMES 3/9/2018 137.34 253779 DOYLE, SALLIE 3/9/2018 410.90 253780 KEYES, MARY 3/9/2018 1,635.92 253781 LUGO, VERONICA 3/9/2018 1,382.70 253782 MCMINN, JAMES 3/9/2018 357.74 253783 PARKER, MARY 3/9/2018 73.00 253784 RODGERS, CHRISTOPHER 3/9/2018 480.00 253785 RODGERS, CHRISTOPHER 3/9/2018 2,196.00 253786 SAMUELS, HARRY 3/9/2018 26.00 253787 WILLIAMS, JULIA 3/9/2018 3.00 253788 ABRIGNANI, MATTEO 3/9/2018 128.26 253789 CACERES, ARTURO 3/9/2018 73.61 253790 CLEAVELIN, WILLIAM JR 3/9/2018 121.53 253791 DANIELL, BREEA 3/9/2018 72.81 253792 GUZMAN, JOE 3/9/2018 106.95 253793 HARRISON, RAYMOND JR 3/9/2018 97.18 253794 HUERTA, JUAN 3/9/2018 164.50 253795 KAUK, KANDY 3/9/2018 98.34 253796 KUNKEL, ROBERT 3/9/2018 119.68 253797 MARTINEZ, DIONICIO III 3/9/2018 105.99 253798 NWOKOCHEN, JOHN 3/9/2018 212.31 253799 RIOS, ROBERT 3/9/2018 65.61 253800 SALERNO, MANUEL 3/9/2018 97.72 253801 SOLIZ, MARK 3/9/2018 126.82 253802 VAZQUEZ, RICARDO 3/9/2018 298.36 253803 AGNEW RESTAURANT SERVICES LLC 3/9/2018 900.00 253804 ALARM SECURITY & CONTRACTING INC 3/9/2018 352.50 253805 AMAZON CAPTIAL SERVICES INC 3/9/2018