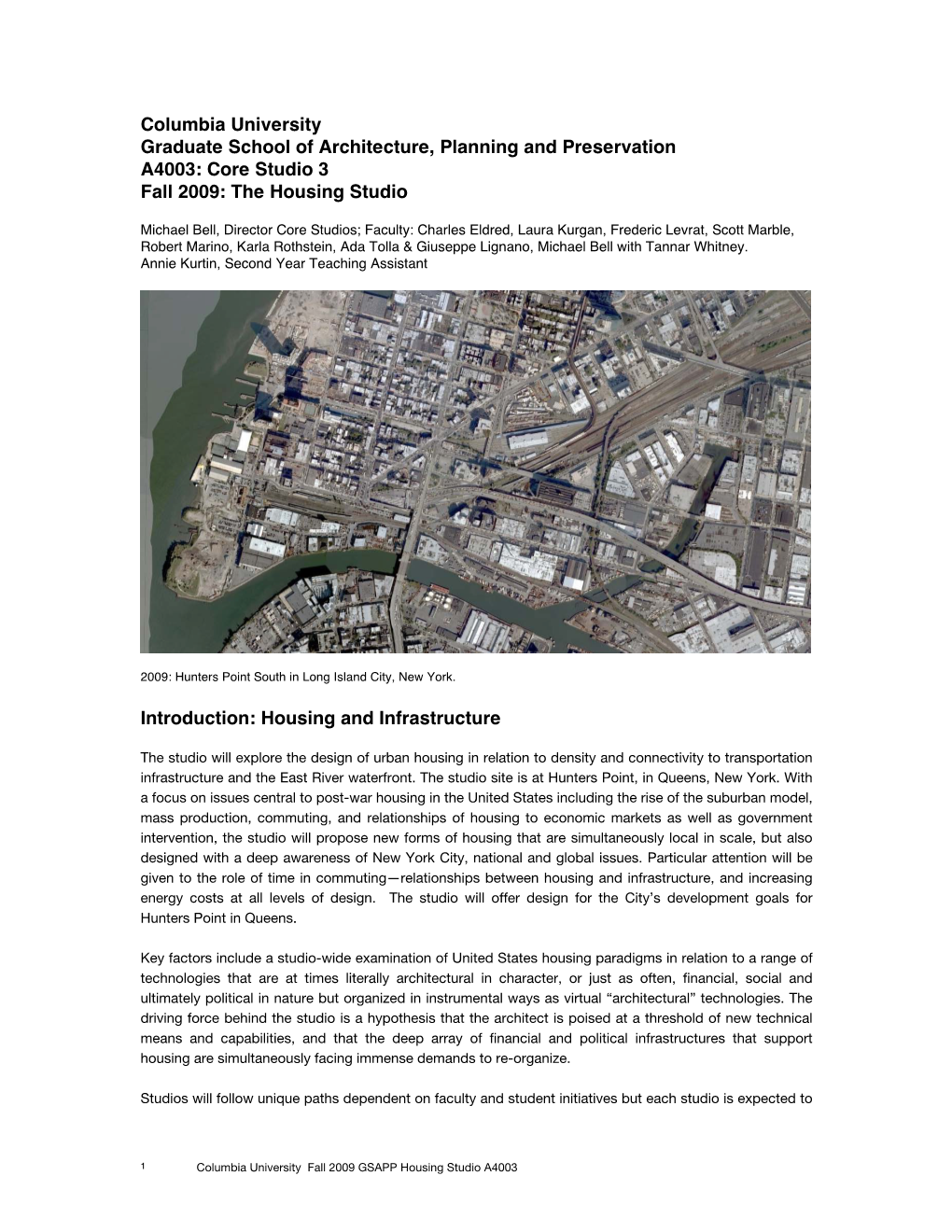

Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation A4003: Core Studio 3 Fall 2009: the Housing Studio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5.1: Land Use, Zoning, and Public Policy A. INTRODUCTION

Chapter 5.1: Land Use, Zoning, and Public Policy A. INTRODUCTION This chapter describes existing land use, zoning, and public policies applicable to the proposed project and evaluates potential significant adverse effects that may result from implementation of the proposed flood protection system. Potential significant adverse effects to land use as a result of implementing the flood protection system are also evaluated. Potential land use issues include known or likely changes in current land uses within the study area, as well as the proposed project’s potential effect on existing and future land use patterns. Potential zoning and public policy issues include the compatibility of the proposed project with existing zoning and consistency with existing applicable public policies. PROJECT AREA ONE Project Area One extends from Montgomery Street on the south to the north end of John V. Lindsay East River Park (East River Park) at about East 13th Street. Project Area One consists primarily of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt East River Drive (FDR Drive) right-of-way, a portion of Pier 42 and Corlears Hook Park as well as East River Park. The majority of Project Area One is within East River Park and includes four existing pedestrian bridges across the FDR Drive to East River Park (Corlears Hook, Delancey Street, East 6th Street, and East 10th Street Bridges) and the East Houston Street overpass. Project Area One is located within Manhattan Community District 3, and borders portions of the Lower East Side and East Village neighborhoods. PROJECT AREA TWO Project Area Two extends north and east from Project Area One, from East 13th Street to East 25th Street. -

Brownfield Cleanup Program Citizen Participation Plan for CE – E

Brownfield Cleanup Program Citizen Participation Plan for CE – E. 11th Street MGP – OU-3 March 2018 Site No. C231105 181 Avenue D New York, NY 10009 www.dec.ny.gov Contents Section Page Number 1. What is New York’s Brownfield Cleanup Program? ............................................. 3 2. Citizen Participation Activities................................................................................ 3 3. Major Issues of Public Concern .............................................................................. 8 4. Site Information ........................................................................................................ 8 5. Investigation and Cleanup Process ..................................................................... 10 Appendix A - Project Contacts and Locations of Reports and Information ...................................................................................................... 13 Appendix B - Site Contact List ................................................................................... 14 Appendix C - Site Location Map................................................................................. 16 Appendix D - Brownfield Cleanup Program Process ............................................... 17 * * * * * Note: The information presented in this Citizen Participation Plan was current as of the date of its approval by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Portions of this Citizen Participation Plan may be revised during the site’s investigation and cleanup process. -

Facts About NYCHA

Facts About NYCHA What is NYCHA? The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) provides decent and affordable housing in a safe and secure living environment for low- and moderate-income residents throughout the five boroughs. To fulfill this mission, NYCHA must preserve its aging housing stock through timely maintenance and modernization of its developments. NYCHA also administers a citywide Section 8 Leased Housing Program in rental apartments. Simultaneously, we work to enhance the quality of life at NYCHA by offering our residents opportunities to participate in a multitude of community, educational, and recreational programs, as well as job readiness and training initiatives. NYCHA was created in 1934. By the end of Broadband Technology Opportunities Program Computer 1935 NYCHA dedicated First Houses, our first Class at Astoria Houses Community Center development, located on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. NYCHA residents and Section 8 voucher holders The Way It Is Today combined occupy 12.0 percent of the City’s rental NYCHA is the largest public housing authority apartments and comprise 7.3 percent of New York in North America. NYCHA’s Conventional Public City’s population. Housing Program has 177,666 (as of March 1, 2015) apartments in 328 developments throughout the City in 2,553 residential buildings containing Conventional Public Housing 3,314 elevators. NYCHA comprises 11,705 (as of March 1, 2015) employees. Our Public Housing developments serve • The Bronx has 89 developments with 44,423 175,747 families and 403,917 authorized residents apartments. (as of January 1, 2015). This includes 3,364 • Brooklyn has 99 developments with 58,454 Section 8 Transition Households (as of January apartments. -

From 'The Projects' to a Sustainable Community: Re-Envisioning

From ‘the projects’ to a sustainable community: Re-envisioning public housing in Lower East-side Manhattan by Mahammad Shamsuddin Momin From ‘the projects’ to a sustainable community: Re-envisioning public housing in Lower East-side Manhattan by Mahammad Shamsuddin Momin A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Urban Design in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in-charge: Professor Peter Bosselmann, Chair Professor John Lund Kriken Professor Malo Hutson Fall 2012 CONTENTS • Abstract .................................................................... i • Acknowledgement ................................................... ii 1. Introduction ........................................................... 1 2. Site Analysis ............................................................ 8 3. Case Studies ........................................................... 30 4. Design Program...................................................... 45 5. Urban Design Framework ..................................... 50 6. Compliance with Zoning Regulations .................. 57 7. Infill Scenarios ....................................................... 66 8. Connectivity ........................................................... 86 9. Accessibility and Green Infrastructure.................. 88 10. Social Integration .................................................. 92 11. Implementation ..................................................... 96 12. Conclusion ............................................................ -

Testimony of State Senator Daniel Squadron Regarding the Draft Annual Plan 2013 for the New York City Housing Authority, July 25, 2012

RANKING MEMBER INVESTIGATIONS AND GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS THE SENATE SOCIAL SERVICES DANIEL SQUADRON STATE OF NEW YORK COMMITTEES SENATOR, 25TH DISTRICT CODES CONSUMER PROTECTION CORPORATIONS, AUTHORITIES & COMMISSIONS FINANCE JUDICIARY TRANSPORTATION TESTIMONY OF STATE SENATOR DANIEL SQUADRON REGARDING THE DRAFT ANNUAL PLAN 2013 FOR THE NEW YORK CITY HOUSING AUTHORITY, JULY 25, 2012. My name is Daniel Squadron and I represent the 25th Senate District in the New York State Senate. My district includes the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Greenpoint, Williamsburg, Vinegar Hill, Fulton Ferry, Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens and Gowanus, and the Manhattan neighborhoods of Tribeca, Battery Park City, the Lower East Side, Chinatown, the Financial District, Little Italy, SoHo and the East Village. Thank you for the opportunity to testify at this hearing. Among the New Yorkers that I represent are the residents of 24 New York City Housing Authority Developments, spanning the Lower East Side, East Village, Willamsburg, and Chinatown. The Manhattan part of my district includes the Bernard Baruch Houses, Marianna Bracetti Houses, Pedro Albizu Campos, East 4th Street Rehab, First Houses, Samuel Gompers Houses, Rafael Hernandez Houses, Fiorello H. LaGuardia Houses, Lower East Side I, II, and III, Lower East Side Rehab, Max Meltzer Tower, Jacob Riis Houses, Henry Rutgers Houses, Seward Park Extension, Alfred E. Smith Houses, Two Bridges, Vladeck Houses, Lillian Wald Houses, and 45 Allen Street. In Brooklyn, I represent three developments: the Taylor Street-Wythe Avenue Houses, Williams Plaza, and Independence Towers. My constituents experience firsthand the challenges described by the New York City Alliance to Preserve Public Housing, and that is why I generally support the recommendations listed in the Alliance’s NYCHA FY 2013 Draft Annual Plan Position Statement. -

The Power of Equity: Private Motivations and Public Implications of Dissolving Affordable Housing Cooperatives

The Power of Equity: Private Motivations and Public Implications of Dissolving Affordable Housing Cooperatives By Jonathan Tarleton B.A. in Latin American Studies University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Chapel Hill, North Carolina (2011) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018 © 2018 Jonathan Tarleton. All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author _______________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 21, 2018 Certified by ____________________________________________________________________ Professor Justin Steil Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by ___________________________________________________________________ Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning The Power of Equity: Private Motivations and Public Implications of Dissolving Affordable Housing Cooperatives By Jonathan Tarleton Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 21, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning Abstract From 1955 to 1978, New York City and state subsidized the construction of over 67,000 middle- income, limited-equity cooperatives in the city through Mitchell-Lama—a program often considered one of the most successful efforts to produce affordable housing in American history. By restricting the resale of shares and removing the housing from the open market, limited-equity co-ops allow for the long-term maintenance of housing affordability and make the benefits of homeownership accessible to lower-income individuals than those served by stereotypical homeownership. -

East Village • Little Italy • Chinatown

Lower East Side EAST VILLAGE • LITTLE ITALY • CHINATOWN Streets & Bridges Cooper Square, B2 Gouverneur St, J10 Pell St, L3 Amalgamated Housing, G10 Chatham Towers, M3 Cooper Square Hotel, C2 First Houses, C5 Holy Trinity Ukrainian Orthodox Church, H3 Lillian Wald Houses, C11 Mulberry Street Branch NY Public Library, F1 Off Soho Suites Hotel, G3 PS 20, E6 St. Stanislaus Church, B5 United Jewish Council, J9 Abraham E. Kazan St, G10 Crosby St, F-H1 Grand St, H8-11, J3 Peretz Square, D6 Angel Orensanz Cultural Center, E6 # Children’s Museum of the Arts, H1 # Cooper Union, A2 First Roumanian American Congregation, F6 Home of the Sages of Israel, G9 Little Missionary Day Nursery, A5 Mulberry Street Theater, K2 # Old Merchant's House, C2 PS 42, J6 St. Theresa RC Church, K7 # US Customs Courthouse, M1 Allen St, F-J5 Delancey St, G4-11 Great Jones St, D2 Pike Slip, M7 Anthology Film Archives, D4 Chinatown Day Care, L4 Cooper Union/Hewitt Building, B2 # First Shearith Israel Graveyard, M4 Hotel 91, L5 Love A Lot Preschool, F7 Museum at Eldridge St/Eldridge St Open Door Senior Citizens Center, H2 PS 63, C5 Sara D. Roosevelt Park, F4, H4 Universal Church, C4 Key Astor Place, B1 Delancey St North, F11 Gustav Hartman Square, D9 Pike St, L6 Assembly of God Church in the Village, B2 Chinatown YMCA, E3 Corlears Hook Park, J12 Forsyth Satellite Academy, E4 Hotel Mulberry, L2 Lower East Side Conservancy, J8 Synagogue, K5 Orpheum Theatre, B4 PS 64, B7 School for Global Leaders, E7 University Neighborhood HS, J10 Attorney St, E8, F8 Division St, K6, L4 Henry -

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 16, 2008, Designation List 405 LP-2263

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 16, 2008, Designation List 405 LP-2263 PUBLIC NATIONAL BANK OF NEW YORK BUILDING (later Public National Bank & Trust Company of New York Building), 106 Avenue C (aka 231 East 7th Street), Manhattan. Built 1923; Eugene Schoen, architect; New York Architectural Terra Cotta Co., terra cotta. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 377, Lot 72. On October 30, 2007, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Public National Bank of New York Building (later Public National Bank & Trust Company of New York Building) and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 7). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Five people spoke in favor of designation, including Councilmember Rosie Mendez and representatives of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, Historic Districts Council, Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America, and New York Landmarks Conservancy. The building’s owner opposed designation. In addition, the Commission received a number of communications in support of designation, including letters from City Councilmember Tony Avella, the Friends of Terra Cotta, Neue Galerie Museum for German and Austrian Art, and City Lore: The New York Center for Urban Folk Culture. Summary The Public National Bank of New York Building in the East Village is a highly unusual American structure displaying the direct influence of the early-twentieth- century modernism of eminent Viennese architect/designer Josef Hoffmann. Built in 1923, the bank was designed by Eugene Schoen (1880-1957), an architect born in New York City of Hungarian Jewish descent, who graduated from Columbia University in 1902, and soon after traveled to Europe, meeting Otto Wagner and Hoffmann in Vienna. -

Appendix A1 List of No Action Projects Mott St Union Square Madison Broadway Fifth Ave Pell St Lafayette St Unionpark Square E Square Park Oliver St Elizabeth St

Appendix A1 List of No Action Projects Mott St Union Square Madison Broadway Fifth Ave Pell St Lafayette St UnionPark Square E Square Park Oliver St Elizabeth St Hester St Bond St Spring St Prince St Kenmare St Grand St Bleecker St Astor Pl Astor Fourth Ave Park Ave S Great Jones St 163 Madison Ave Bowery Cooper Catherine St S quare Monroe St Irving Pl Canal St Chrystie St South St Stuyvesant St Division St Delancey St ! Forsyth St E 16th St Market St 72 Eldridge St ! ! Park Ave E 19th St 69 49 E 27th St E 5th St E 28th St ! Lexington Ave E 1st St ! 138 ! E 22nd St ! Allen St E 15th St 99 112 50 E 31st St 19 52 E 17th St E 24th St ! Rutherford Pl E 18th St ! Pike St Orchard St Third Ave 94 E 32nd St ! ! 27 144 ! 133 ! 95 St Marks Pl ! 89 158 57 Pike Slip ! 24 Ludlow St Second Ave ! Cherry St 51 Henry St 85 154 E 26th St 42 Essex St E 12th St E 29th St ! E 13th St E 2nd St ! E 21st St E 25th St E 30th St ! 14 ! Madison St 82 E 4th St E 11th St 40 Rutgers St Seward ! 140 Park 15 60 162 Norfolk St Manhattan Bridge ! ! 139 114 ! Rutgers Slip Rivington St ! E 33rd St ! 1 ! 93 ! 56 117 E 10th St 152 ! Suffolk St 135 78 35 142 ! 45 E 3rd St 47 First Ave 39 161 E 9th St 106! 68 160 120 126 110 157 E 20th St ! St 97 164 Stanton! St E 7th St 1 ton E ! Avenue A ! st lin a 159 ! 108 ! A C s 119 ve 38 90 ! 156 Loop d t 141 ! E 6th St 86 R B ! 11 21 r 128 98 r o 104 79 ! e a 46 ! ! p d 102! 103 44 ! Avenue B Tompkins 145 o E 23rd St w o h ! 84 t 153 C a 155 Square Park 63 r Pier 36 P ! ! 25 y ! 125 Broome St ! 36 ! Ridge St 118 66 ! 150 te d 71 e E -

NYCHA-Appendices 121715.Pdf

Programmatic Environmental Assessment New York City Housing Authority Public Housing Resiliency TABLE OF CONTENTS: APPENDICES APPENDIX A: Documents..............................................................................................................2 Document A – Record of Environmental Consideration ......................................3 Document B – Utility Management Project ........................................................11 Document C – 8-Step Floodplain Review ..........................................................15 Document D – Proposed NYCHA Development Project ...................................27 APPENDIX B: Figures ..................................................................................................................30 Figure A – Geological Map of the Project Area .................................................31 Figure B – Asian Longhorn Beetle Quarantine Zone ........................................33 Figure C – Coastal Zone..................................................................................... .35 APPENDIX C: Tables ...................................................................................................................3 7 Table A – Thresholds that Would Trigger a Site Specific EA ...........................39 Table B – NYCHA Development s .....................................................................4 3 Table C – New York State NAAQS levels.........................................................47 Table D – Minority Population by Census Block...............................................50 -

Housing Studios Were Perhaps More Overtly Activist at Their Inception Then They Actually Were

Columbia University 1 Manhattan’s Lower East Side: Housing and the City of New York GSAP: Housing Studio Fall 2003 Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation 400 Avery Hall: 1172 Amsterdam Avenue: New York, NY 10027 Michael Bell, Charles Eldred, Mario Gooden, Sulan Kolatan, Craig Konyk, Robert Marino, Karla Rothstein, Yoshiko Sato Ben Krone, Teaching Assistant 0: Introduction: Oppositions and the Conservative House The Public’s "The first principle of association guarantees the "free exercise of his industry and the fruits acquired by it." Thomas Jefferson Private When the first public housing projects were proposed in the United States there was immediate and strong Apartment reaction from housing developers and banking associations that accused the programs of being "unfair government competition." In 1938, three years after the formation of the New York Housing Authority, the newly formed Housing Authority of Houston faced strong resistance that declared the agency to be Start_The role of housing in Socialist competition with the free market.3 Today, 62 years later, at the outset of a new federal housing New York City has a renewed initiative that offers assistance to families to purchase rather than rent a dwelling the debate has come full sense of potential as it finds circle. Current housing policies in the United States have, to an unprecedented degree, forgone the con- itself at the center of new struction of collective and financially subsidised rental housing and focused government housing initiatives urban initiatives that rely on in the open market of private developers and the single-family house or low rise townhouse/condominium. -

The City Record � � Vol

THE CITY RECORD VOL. LX XIV NUMBER 22266 NEW YORK, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 1946 PRICE 10 CENTS THE CITY RECORD MUNICIPAL CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION cel#D 155 OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK Applications are being received continuously for the following license examina- Published Under Authority of Section 872-a of the New York City Charter tions: Master and Special Electrician; Master Plumber; Master Rigger; Motion STEPHEN G. KELLEY, SUPERVISOR Picture Operator ; Portable Engineer (any motive power except steam); Portable WILLIAM VIERTEL, EDITOR Engineer (steam) ; Refrigerating Machine Operator (ten ton capacity) ; Refriger- 2213 Municipal Building, Manhattan, N. Y. 7. WO rth 2.1800 ating Machine Operator (unlimited capacity); Special Rigger; Stationary Engi- neer, First, Second and Third Grades ; Stationary Fireman; Structural Welder; Published daily, at 9 a. m., except Sundays and legal holidays. Oil Burning Equipment Installation. Subscription: $20 a year; $10 six months; $5 three months. Daily issue, 10 cents a copy (by mail, 15 cents). License applications and detailed information may be obtained at the Applica- Entered as Second-Class Matter, Post Office at New York, N. Y. tion Bureau of the Municipal Civil Service Commission, 96 Duane Street, Man- OTHER CITY RECORD PUBLICATIONS hattan, N. Y. 7. Order must be accompanied by currency, money order, or check drawn to the order of "Supervisor of THE CITY RECORD." Checks for $3 nr more must be certified. By Mail By Mail Assessed Valuation of Real Estate Yor1, City Charter and Ad- OFFICE OF THE MAYOR (106 Sections) Prices Vary. ministrative Code, Amendments to- Canvass of Votes $1.00 $1.10 Cumulative to July 1, 1941 $1.00 $1.10 Election Law Decisions.