Ball Brothers Glass Mfg. Co

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ball State Experience Pen Point Ball State ALUMNUS Executive Publisher: Edwin D

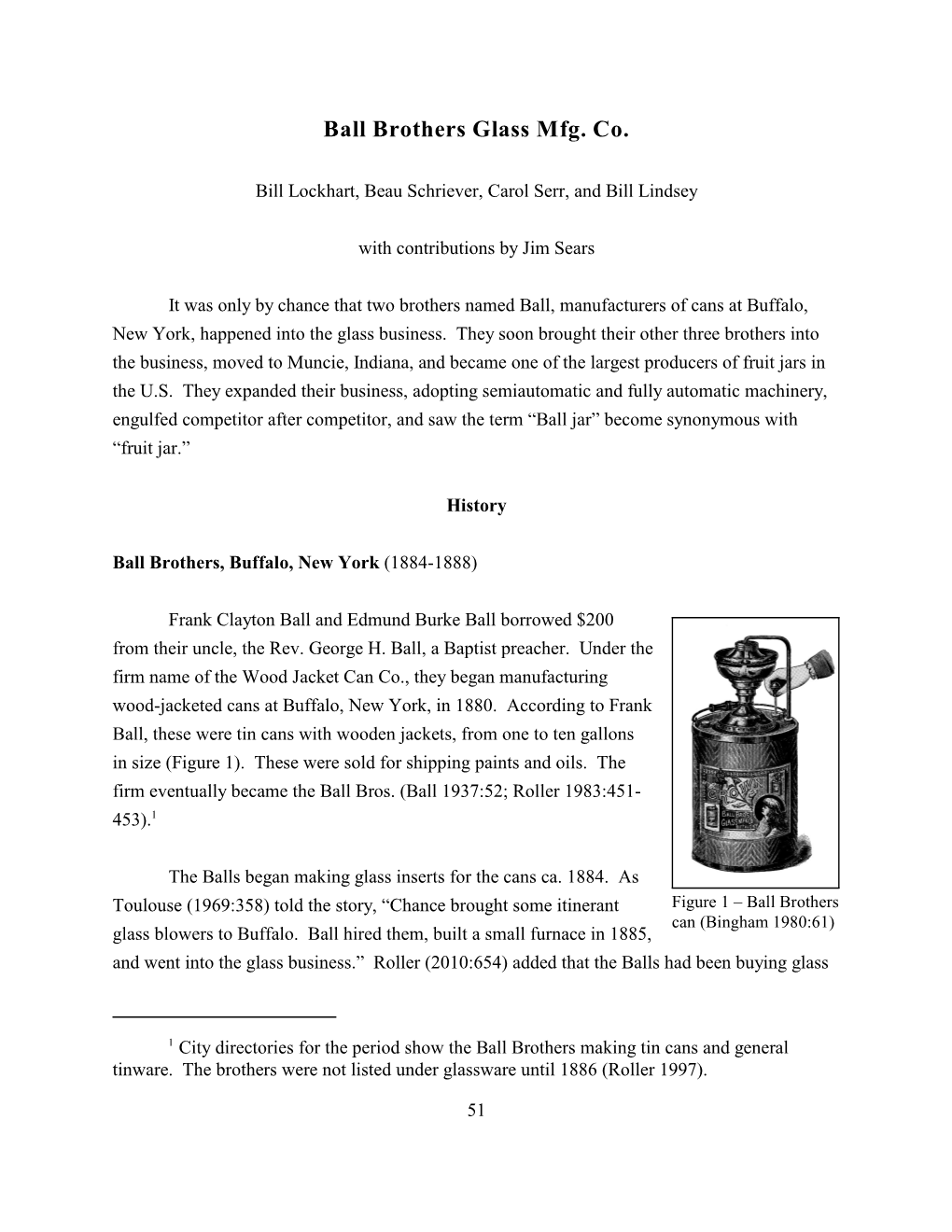

cover layout:Layout 1 2/19/08 8:58 PM Page 1 Inside This Issue A Ball State University Alumni Association Publication March 2008 Vol. 65 No.5 Beyond the Classroom 10 Sidelines 28 40 under 40 33 Linda Huge fulfills a mission of keeping Hoosier history alive through her role as self-appointed school marm of a one-room schoolhouse in Fort Wayne. See the story on page 4. Ball State University NON-PROFIT ORG. Alumni Association U.S. POSTAGE Muncie, IN 47306-1099 PAID Huntington, IN Permit No. 832 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED The Ball State experience pen point Ball State ALUMNUS Executive Publisher: Edwin D. Shipley Editor: Charlotte Shepperd Communications Assistant: Julie Johnson f you don’t pass history on, it’s gone," according to 1959 Ball State graduate Linda Alumnus Assistants: Denise Greer, Jessica Riedel Huge. She has made it her full-time mission to educate Hoosiers on the history of Graduate Communications Assistants: their state as curator of a one-room schoolhouse in Fort Wayne. Huge’s story, on Danya Pysh, Katherine Tryon "I Undergraduate Communications Assistant: pages 4-5, describes how the self-appointed schoolmarm takes her personal passion for Sarah Davison history and instills listeners, both young and old, with knowledge. Contributing Writers: Th omas L. Farris Photographers: Sarah Davison, Steve Fulton, Ball State’s history as a public institution dates to 1918 when the Ball Brothers, after they Mike Hickey, John Huff er, Robin Jerstad had purchased it in 1917, gave 64-plus acres and two buildings to the state. Thereafter, we (Indianapolis Business Journal), Ernie Krug, Don Rogers became the Eastern Division of the Indiana State Normal School in Terre Haute. -

Social Studies Grades K-5

Social Studies Grades k-5 History – Historical Knowledge, Chronological Thinking, Historical Comprehension, Analysis and Interpretation, Research (General History – K – 2) : Kindergarten Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 K.1.1.a.1: Observe 1.1.1.a.1: Observe 2.1.1.a.1: Find or 3.1.1.a.1: Identify 4.1.1.a.1: Identify 5.1.1.a.1: Identify and tell about and tell about the match the name of Native American the major early groups of people children and way individuals in the local Woodland Indians cultures that who settled in North families of today the community lived community, the who lived in the existed in the America prior to and those from the in the past with the year it was region when region that became contact with past. way they live in the founded, and the European settlers Indiana prior to Europeans. present. arrived. contact with name of the Example: Miami, Europeans. founder. Shawnee, Kickapoo, Algonquian, Delaware, Potawatomi and Wyandotte. (http://www.conner prairie.org/Learn- And-Do/Indiana- History/America- 1800- 1860/Native- Americans-In- America.aspx) K.1.2.a.1: Identify 1.1.2.a.1: With 2.1.2.a.1: Use 3.1.2.a.1: Identify 4.1.2.a.1: Identify 5.1.2.a.1: Examine people, guidance and maps, photographs, founders and early historic Native how early celebrations, support, observe news stories, settlers of the local American Indian European commemorations, and tell about past website or video to community. -

Repurposing Maplewood Mansion

PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES Ball Brothers Foundation 2017 Annual Report Jud Fisher, president and chief operating officer, and James Fisher, chairman and chief executive officer, are photographed in front of the Edmund F. Ball Medical Education Building. PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES “Medicine has changed a lot in the past 100 years, but medical training has not. Until now.” —JULIE ROVNER, Kaiser Health News FRIENDS, IN THIS YEAR’S ANNUAL REPORT we focus on a cluster of grants Among other highlights of 2017: that emerged after two and a half years of conversations with community colleagues who share an ambitious goal: to push • We topped last year’s record-setting grants payout by traditional boundaries and experiment with new models of awarding $7.3 million to nonprofit organizations in Muncie, healthcare education and delivery. The project that we call “Optimus Delaware County, and East Central Indiana. Primary” is in its earliest stages and, like any learning initiative, will • We stepped up our efforts as a community convener by hosting likely undergo refinements as it unfolds. Our initial partners—IU a downtown visioning summit; inviting Indiana’s governor to Health Ball Memorial Hospital, the IU School of Medicine-Muncie, a gathering of healthcare professionals; engaging workforce Meridian Health Services, and Ball State University—are providing development professionals and postsecondary education the leadership. BBF’s role is to serve as a catalyst by making strategic leaders in a listening session with Indiana’s newly appointed grants that help move ideas to implementation. secretary of career connections and talent; and organizing a bus tour with BBF’s board of directors to acquaint BSU’s new In many ways Optimus Primary continues the Ball family tradition president with BBF-funded projects in Delaware County. -

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection 1839.6.681 Book John Marshall The Writings of Chief Justice Marshall on the Federal 1839 GCM-KTM Constitution 1845.6.878 Book Unknown The Proverbs and other Remarkable Sayings of Solomon 1845 GCM-KTM 1850.6.407 Book Ik Marvel Reveries of A Bachelor or a Book of the Heart 1850 GCM-KTM The Analogy of Religion Natural and Revealed, to the 1857.6.920 Book Joseph Butler 1857 GCM-KTM Constitution and Course of Nature 1859.6.1083 Book George Eliot Adam Bede 1859 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.1 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.2 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.1 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.2 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.162 Book Charles Dickens Great Expectations: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.163 Book Charles Dickens Christmas Books: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.1 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.2 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1871.6.359 Book James Russell Lowell Literary Essays 1871 GCM-KTM 1876.6. -

T********************************************* Reproductlons Supplied by EDRS Are Thc Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 346 263 CE 061 270 AUTHOR Erickson, Judith B. TITLE Indiana Youth Poll: Youths' Views of Life beyond High School. INSTITUTION Indiana Youth Inst., Indianapolis. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 76p.; For views of high school life, see ED 343 283. AVAILABLE FROM Indiana Youth Institute, 333 North Alabama Street, Suite 200, Indianapolis, IN 46204 ($7.50 plus $2.50 postage and handling). PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Aspiration; Career Choice; *Career Planning; *Education Work Relationship; Futures (of Society); Goal Orientation; High Schools; *High School Students; Occupational Aspiration; Parent Background; State Surveys; Student Attitudes; *Student Educational Objectives; *Student Employment; Student Interests; Success; Youth IDENTIFIERS *Indiana Youth Poll ABSTRACT The Indiana Youth Poll examined youna people's doubts, hopcs, and dream3 for the future. Participants responded in two ways: they replied as individuals to a short questionnaire and participated in discussions on open-ended questions. Altogether, 1,560 students from 204 of Indiana's public high schools and from 20 of the 293 private high schools participated. Findings related to students' present employment showed the following: they worked 10-20 hours per week; with age came a steady increase in number of hou s worked; there were gender and age differences in jo'Js reported; and nearly 4 in 10 job-holders saw no relationship between their current jobs and career aspirations. Answers to questions regarding educational and career plans indicated that a majority expected to finish high school; 74.2 percent felt they ought to go to college right after high school. -

All Indiana State Historical Markers As of 2/9/2015 Contact Indiana Historical Bureau, 317-232-2535, [email protected] with Questions

All Indiana State Historical Markers as of 2/9/2015 Contact Indiana Historical Bureau, 317-232-2535, [email protected] with questions. Physical Marker County Title Directions Latitude Longitude Status as of # 2/9/2015 0.1 mile north of SR 101 and US 01.1977.1 Adams The Wayne Trace 224, 6640 N SR 101, west side of 40.843081 -84.862266 Standing. road, 3 miles east of Decatur Geneva Downtown Line and High Streets, Geneva. 01.2006.1 Adams 40.59203 -84.958189 Standing. Historic District (Adams County, Indiana) SE corner of Center & Huron Streets 02.1963.1 Allen Camp Allen 1861-64 at playground entrance, Fort Wayne. 41.093695 -85.070633 Standing. (Allen County, Indiana) 0.3 mile east of US 33 on Carroll Site of Hardin’s Road near Madden Road across from 02.1966.1 Allen 39.884356 -84.888525 Down. Defeat church and cemetery, NW of Fort Wayne Home of Philo T. St. Joseph & E. State Boulevards, 02.1992.1 Allen 41.096197 -85.130014 Standing. Farnsworth Fort Wayne. (Allen County, Indiana) 1716 West Main Street at Growth Wabash and Erie 02.1992.2 Allen Avenue, NE corner, Fort Wayne. 41.078572 -85.164062 Standing. Canal Groundbreaking (Allen County, Indiana) 02.19??.? Allen Sites of Fort Wayne Original location unknown. Down. Guldin Park, Van Buren Street Bridge, SW corner, and St. Marys 02.2000.1 Allen Fort Miamis 41.07865 -85.16508333 Standing. River boat ramp at Michaels Avenue, Fort Wayne. (Allen County, Indiana) US 24 just beyond east interchange 02.2003.1 Allen Gronauer Lock No. -

Educator Resource Guide

2015-2016 SCHOOL YEAR EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE 1 Table of Contents What Teachers and 3 DEAR TEACHERS Students are Saying 4 GENERAL INFORMATION “State and local history is a ‘hook’ that engages students in the past. It doesn’t 5 FIELD TRIPS AT THE HISTORY CENTER matter if students are from India or Japan or your hometown, local and 6 OPTIONAL ADD ON PROGRAMS FOR FIELD TRIPS state history is accessible because it is 7 YOU ARE THERE 1816: INDIANA JOINS THE NATION right outside the school window!” – Teacher 8 YOU ARE THERE: THAT AYRES LOOK “[IHS has] fantastic different websites, 9 YOU ARE THERE 1904: PICTURE THIS primary sources and people to contact 10 YOU ARE THERE 1948: COMMUNITIES CAN! for help!” – Teacher 11 NATIONAL HISTORY DAY “Love all the websites and Hoosiers and the American Story. As an English 13 BRING A HISTORICAL INTERPRETER TO YOUR SCHOOL teacher, we are asked to teach nonfiction, and history is perfect for 14 GROWING LITTLE LEAVES that.” – Teacher 15 ADDITIONAL EDUCATOR RESOURCES “I’m a reference person at a public 16 BICENTENNIAL TEACHER WORKSHOPS library and this will be a great program for our patrons and their children.” 17 DESTINATION INDIANA ONLINE – Growing Little Leaves participant 18 HOOSIERS AND THE AMERICAN STORY ORDER FORM “Participating in History Day makes you look at history differently – you 19 IHS PRESS BOOKS begin to see that you were a part of history.” –Student 2 Dear Teachers, Welcome! We in the Education and Community Engagement Department of the Indiana Historical Society wish you a successful, meaningful 2015-16 school year. -

Muncie, Indiana

Fall 2019 ALLIANCE A Gift for Giving Compassion in Our Community INSIDE: Tonne Winery in the Spotlight FORFOR THETHE GO-GETTERSGO-GETTERS GENBNK-ADPR-ALLIANCE-0919 GENBNK-ADPR-ALLIANCE-0919 COMMERCIAL BANKING | PERSONAL BANKING | PRIVATE WEALTH COMMERCIAL BANKING | PERSONAL BANKING | PRIVATE WEALTH GENBNK-ADPR-ALLIANCE-0919 GENBNK-ADPR-ALLIANCE-0919 Somehow, life got faster. We understand. When you need nimble, First Merchants is ready to roll. When you need Somehow, life got faster. We understand. When you need nimble, First Merchants is ready to roll. When you need a foundation, we’re your bedrock. So if you’re a go-getter, an up-and-comer or an early riser, First Merchants can a foundation, we’re your bedrock. So if you’re a go-getter, an up-and-comer or an early riser, First Merchants can provide the tools to make your life as efficient as possible. For more information go to firstmerchants.com. provide the tools to make your life as efficient as possible. For more information go to firstmerchants.com. firstmerchants.comfirstmerchants.com 765-213-3493765-213-3493 Deposit accounts and loan products are offered by First Merchants Bank, Member FDIC, Equal Housing Lender. Deposit accounts and loan products are offered by First Merchants Bank, Member FDIC, Equal Housing Lender. First Merchants Private Wealth Advisors products are not FDIC insured, are not deposits of First Merchants Bank, are not guaranteed by any federal First Merchants Private Wealth Advisors products are not FDIC insured, are not deposits of First Merchants Bank, are not guaranteed by any federal government agency, and may lose value. -

2018 Annual Report KEEP the BALL JAR Your Year-Round Gathering Place ROLLING

2018 annual report KEEP THE BALL JAR your year-round gathering place ROLLING 1200 n. minnetrista pkwy. minnetrista.net muncie, in 47303 765.282.4848 In My Hands, In My Heart 2018 year in review Indiana Arts Commission 2018 Adding It All Up Minnetrista’s theater outreach programming was boosted by an Arts Project Support grant from the Indiana Arts 30 years in the can! Commission. The Arts Commission uses public funding from the National Endowment for the Arts to make art experiences accessible to Hoosiers across the state. The grant supported the creation of In My Hands, In My Heart, an original theatrical Operating Revenue Operating Expenses 2018 Visits | 104,279 production that uses the discovery of a Ball jar embossed with the KKK insignia to explore perspectives on racial tension. I mean, jar! The production was a success and wouldn’t have been possible without the support of the Indiana Arts Commission, the $2,450,000 Ball Brothers Foundation $2,298,980 Programs Visitors enjoyed the many exhibits hosted in our gallery spaces: Community Foundation of Randolph County, and the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. 1948 Communities Can $1,050,000 George and Frances Ball Foundation $849,138 Facilities & Grounds Sometimes the simplest way to deliver a message is also the best way. So … $610,709 Earned Revenue $547,177 Administration An exhibit traveling back in time to explore the impact that Ball Brothers Company from Muncie, Indiana had on Thank You! Thank you for all you have done over the past 30+ years to make Catalyst Restoration $278,037 Contributed Revenue $206,318 Development the food preservation movement across the United States. -

The First Year of Ball State: Personal and Policy Conflicts, 1918-1919 An

,- I The First Year of Ball State: Personal and Policy Conflicts, 1918-1919 An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Alan P. Hagedon -- Thesis Advisor Dr. Tony Edmonds ~0L-. Ball State University Muncie, Indiana Date 16 June 1995 Expected date of graduation May 1995 --1- ( ... __ , ,_ : I ~ ,--.- ; --I Purpose of Thesis This paper discusses the various issues confronted between 1918 and 1919 by the Eastern Division of the Indiana State Normal School which became Ball State Teacher's College. The primary emphasis is placed upon how the administrators and faculty approached and dealt with the controversies and conflicts during this school's first year of operation. Letters of correspondence between the Eastern Division and the Terre Haute Division of Indiana State Normal School were the most crucial resource by which the dialogue between the two schools was reconstructed. -I - 1 This paper will deal with four of the issues that Ball State faced during its first year of operation. Ball State University, called the Eastern Division in 1918, was started as an extension branch of Indiana State University, then known as Indiana State Normal School (I.S.N.S.) (1). This new division of the Indiana State Normal School was the result of the circumstances and opportunities facing I.S.N.S. in 1918. The state of Indiana needed more and better teachers, but I.S.N.S. could not by itself meet this need (2). Moreover I.S.N.S. was faced with a surplus of faculty, since World War I led to a decrease in student enrollment (3). -

University President Leadership Profile Ball State University • 2000 West University Avenue • Muncie, in • 47306 a the Role of the President

University President Leadership Profile Ball State University • 2000 West University Avenue • Muncie, IN • 47306 A The Role of the President he next president of Ball State officials, and others closely associated with the their appreciation for the value that Ball University will be an engaged, university. Finally, the president will lead by State University provides to the citizens of Tinspiring leader with a demonstrated modeling character, passion, integrity, and the Muncie, Delaware County, and the state commitment to Ball State’s heritage, mission, pursuit of knowledge. of Indiana and core values. The president will advance The president’s principal duties are to: • strengthen partnerships with the business those values by building on the university’s community, area school districts and traditions and strengths, actively seeking • articulate and advance the mission and core other institutions of education, and consensus among all its constituencies, and values of Ball State University residents of the local and regional exercising superb management and decision- • ensure that the university pursues and communities, with an entrepreneurial making skills. The president will communicate achieves excellence in its academic spirit that helps build new revenue streams effectively with both internal and external endeavors, including but not limited and increases student achievement constituencies, articulating clearly and to quality undergraduate and graduate passionately Ball State’s mission and strategic academic offerings, regional and national • encourage alumni involvement in the aspirations. She or he will work effectively recognition of scholarly and creative university and its activities with the chair and trustees of Ball State’s board activities of the faculty, and the achievement • lead aggressive efforts to raise funds from in pursuit of the strategic initiatives that will and success of its students individual donors, private and nonprofit further strengthen the university and the sources, state appropriations, government community. -

SENATOR WILLIAH B. PINE and HIS TIMES by MAYNARD J. HANSON Bachelor of Arts Yankton College Yankton, South Dakota 1969 Master Of

SENATOR WILLIAH B. PINE AND HIS TIMES By MAYNARD J. HANSON ~ Bachelor of Arts Yankton College Yankton, South Dakota 1969 Master of Arts University of South Dakota Vermillion, South Dakota 1974 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1983 -n. .,"'.":~ I q•z, -~ 1:1 ·~ 35;;L~ ~,J- Copyright by Maynard J. Hanson May, 1983 SENATOR WILLIAM B. PINE AND HIS TIMES Thesis Approved: ~sis . AdVi . er ~ ~ - ~ ) Dean of Graduate College ii PREFACE This is an examination of the career of William B. Pine, a businessman and politician from Okmulgee, Oklahoma. His business experiences stretched from territorial days to World War II and involved oil, manufacturing, and agricul ture. Pine achieved political recognition in the 1924 elections, made distinctive by the involvement of the Ku Klux Klan, when he defeated the Democratic nominee, John C. Walton, for a seat in the United States Senate. Initially aligned with regular Republicans in the Senate, Pine gradu ally became more critical of the Hoover administration. He sought re-election in 1930 and lost to Thomas P. Gore. A campaign for the Oklahoma governorship ended in defeat in 1934. He was preparing another senatorial bid when he died in 1942. The author greatly appreciates the professional advice and extensive assistance of his major adviser, Dr. Theodore L. Agnew, in the preparation of this study. The author also is grateful for the contributions made by Dr. Ivan Chapman, Dr. Douglas D. Hale, and Dr. LeRoy H.