Arthur Kornberg Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itcontents 9..22

INTERNATIONAL TABLES FOR CRYSTALLOGRAPHY Volume F CRYSTALLOGRAPHY OF BIOLOGICAL MACROMOLECULES Edited by MICHAEL G. ROSSMANN AND EDDY ARNOLD Advisors and Advisory Board Advisors: J. Drenth, A. Liljas. Advisory Board: U. W. Arndt, E. N. Baker, S. C. Harrison, W. G. J. Hol, K. C. Holmes, L. N. Johnson, H. M. Berman, T. L. Blundell, M. Bolognesi, A. T. Brunger, C. E. Bugg, K. K. Kannan, S.-H. Kim, A. Klug, D. Moras, R. J. Read, R. Chandrasekaran, P. M. Colman, D. R. Davies, J. Deisenhofer, T. J. Richmond, G. E. Schulz, P. B. Sigler,² D. I. Stuart, T. Tsukihara, R. E. Dickerson, G. G. Dodson, H. Eklund, R. GiegeÂ,J.P.Glusker, M. Vijayan, A. Yonath. Contributing authors E. E. Abola: The Department of Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research W. Chiu: Verna and Marrs McLean Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA. [24.1] Biology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030, USA. [19.2] P. D. Adams: The Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Department of Molecular J. C. Cole: Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge Biophysics and Biochemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA. CB2 1EZ, England. [22.4] [18.2, 25.2.3] M. L. Connolly: 1259 El Camino Real #184, Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA. F. H. Allen: Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge [22.1.2] CB2 1EZ, England. [22.4, 24.3] K. D. Cowtan: Department of Chemistry, University of York, York YO1 5DD, U. W. Arndt: Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Medical Research Council, Hills England. -

Biochemistrystanford00kornrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Program in the History of the Biosciences and Biotechnology Arthur Kornberg, M.D. BIOCHEMISTRY AT STANFORD, BIOTECHNOLOGY AT DNAX With an Introduction by Joshua Lederberg Interviews Conducted by Sally Smith Hughes, Ph.D. in 1997 Copyright 1998 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Arthur Kornberg, M.D., dated June 18, 1997. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Lecture Program

EARL W. SUTHERLAND LECTURE EARL W. SUTHERLAND LECTURE The Earl W. Sutherland Lecture Series was established by the SPONSORED BY: Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics in 1997 DEPARTMENT OF MOLECULAR PHYSIOLOGY AND BIOPHYSICS to honor Dr. Sutherland, a former member of this department and winner of the 1971 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. This series highlights important advances in cell signaling. ROBERT J. LEFKOWITZ, MD NOBEL PRIZE IN CHEMISTRY, 2012 SPEAKERS IN THIS SERIES HAVE INCLUDED: SEVEN TRANSMEMBRANE RECEPTORS Edmond H. Fischer (1997) Alfred G. Gilman (1999) Ferid Murad (2001) Louis J. Ignarro (2003) MARCH 31, 2016 Paul Greengard (2007) 4:00 P.M. 208 LIGHT HALL Eric Kandel (2009) Roger Tsien (2011) Michael S. Brown (2013) 867-2923-Institution-Discovery Lecture Series-Lefkowitz-BK-CH.indd 1 3/11/16 9:39 AM EARL W. SUTHERLAND, 1915-1974 ROBERT J. LEFKOWITZ, MD JAMES B. DUKE PROFESSOR, Earl W. Sutherland grew up in Burlingame, Kansas, a small farming community DUKE UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER that nourished his love for the outdoors and fishing, which he retained throughout INVESTIGATOR, HOWARD HUGHES MEDICAL INSTITUTE his life. He graduated from Washburn College in 1937 and then received his MEMBER, NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES M.D. from Washington University School of Medicine in 1942. After serving as a MEMBER, INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE medical officer during World War II, he returned to Washington University to train NOBEL PRIZE IN CHEMISTRY, 2012 with Carl and Gerty Cori. During those years he was influenced by his interactions with such eminent scientists as Louis Leloir, Herman Kalckar, Severo Ochoa, Arthur Kornberg, Christian deDuve, Sidney Colowick, Edwin Krebs, Theodore Robert J. -

Medical Advisory Board September 1, 2006–August 31, 2007

hoWard hughes medical iNstitute 2007 annual report What’s Next h o W ard hughes medical i 4000 oNes Bridge road chevy chase, marylaNd 20815-6789 www.hhmi.org N stitute 2007 a nn ual report What’s Next Letter from the president 2 The primary purpose and objective of the conversation: wiLLiam r. Lummis 6 Howard Hughes Medical Institute shall be the promotion of human knowledge within the CREDITS thiNkiNg field of the basic sciences (principally the field of like medical research and education) and the a scieNtist 8 effective application thereof for the benefit of mankind. Page 1 Page 25 Page 43 Page 50 seeiNg Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Südhof: Paul Fetters; Fuchs: Janelia Farm lab: © Photography Neurotoxin (Brunger & Chapman): Page 3 Matthew Septimus; SCNT images: by Brad Feinknopf; First level of Rongsheng Jin and Axel Brunger; iN Bruce Weller Blake Porch and Chris Vargas/HHMI lab building: © Photography by Shadlen: Paul Fetters; Mouse Page 6 Page 26 Brad Feinknopf (Tsai): Li-Huei Tsai; Zoghbi: Agapito NeW Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Arabidopsis: Laboratory of Joanne Page 44 Sanchez/Baylor College 14 Page 8 Chory; Chory: Courtesy of Salk Janelia Farm guest housing: © Jeff Page 51 Ways Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Institute Goldberg/Esto; Dudman: Matthew Szostak: Mark Wilson; Evans: Fred Page 10 Page 27 Septimus; Lee: Oliver Wien; Greaves/PR Newswire, © HHMI; Mello: Erika Larsen; Hannon: Zack Rosenthal: Paul Fetters; Students: Leonardo: Paul Fetters; Riddiford: Steitz: Harold Shapiro; Lefkowitz: capacity Seckler/AP, © HHMI; Lowe: Zack Paul Fetters; Map: Reprinted by Paul Fetters; Truman: Paul Fetters Stewart Waller/PR Newswire, Seckler/AP, © HHMI permission from Macmillan Page 46 © HHMI for Page 12 Publishers, Ltd.: Nature vol. -

Mapping Our Genes—Genome Projects: How Big? How Fast?

Mapping Our Genes—Genome Projects: How Big? How Fast? April 1988 NTIS order #PB88-212402 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Mapping Our Genes-The Genmne Projects.’ How Big, How Fast? OTA-BA-373 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1988). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 87-619898 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402-9325 (order form can be found in the back of this report) Foreword For the past 2 years, scientific and technical journals in biology and medicine have extensively covered a debate about whether and how to determine the function and order of human genes on human chromosomes and when to determine the sequence of molecular building blocks that comprise DNA in those chromosomes. In 1987, these issues rose to become part of the public agenda. The debate involves science, technol- ogy, and politics. Congress is responsible for ‘(writing the rules” of what various Federal agencies do and for funding their work. This report surveys the points made so far in the debate, focusing on those that most directly influence the policy options facing the U.S. Congress, The House Committee on Energy and Commerce requested that OTA undertake the project. The House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, the Senate Com- mittee on Labor and Human Resources, and the Senate Committee on Energy and Natu- ral Resources also asked OTA to address specific points of concern to them. Congres- sional interest focused on several issues: ● how to assess the rationales for conducting human genome projects, ● how to fund human genome projects (at what level and through which mech- anisms), ● how to coordinate the scientific and technical programs of the several Federal agencies and private interests already supporting various genome projects, and ● how to strike a balance regarding the impact of genome projects on international scientific cooperation and international economic competition in biotechnology. -

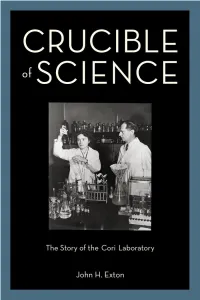

Crucible of Science: the Story of the Cori Laboratory

Crucible of Science This page intentionally left blank Crucible of Science THE STORY OF THE CORI LABORATORY JOHN H. EXTON 3 3 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitt ed by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. CIP data is on fi le at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–986107–1 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Dedicated to Charles Rawlinson (Rollo) Park This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix I n t r o d u c t i o n xi 1. -

Moore Noller

2002 Ada Doisy Lectures Ada Doisy Lecturers 2003 in BIOCHEMISTRY Sponsored by the Department of Biochemistry • University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Dr. Peter B. 1970-71 Charles Huggins* and Elwood V. Jensen A76 1972-73 Paul Berg* and Walter Gilbert* Moore 1973-74 Saul Roseman and Bruce Ames Department of Molecular carbonyl Biophysics & Biochemistry Phe 1974-75 Arthur Kornberg* and Osamu Hayaishi Yale University C75 1976-77 Luis F. Leloir* New Haven, Connecticutt 1977-78 Albert L. Lehninger and Efraim Racker 2' OH attacking 1978-79 Donald D. Brown and Herbert Boyer amino N3 Tyr 1979-80 Charles Yanofsky A76 4:00 p.m. A2486 1980-81 Leroy E. Hood Thursday, May 1, 2003 (2491) 1983-84 Joseph L. Goldstein* and Michael S. Brown* Medical Sciences Auditorium 1984-85 Joan Steitz and Phillip Sharp* Structure and Function in 1985-86 Stephen J. Benkovic and Jeremy R. Knowles the Large Ribosomal Subunit 1986-87 Tom Maniatis and Mark Ptashne 1988-89 J. Michael Bishop* and Harold E. Varmus* 1989-90 Kurt Wüthrich Dr. Harry F. 1990-91 Edmond H. Fischer* and Edwin G. Krebs* 1993-94 Bert W. O’Malley Noller 1994-95 Earl W. Davie and John W. Suttie Director, Center for Molecular Biology of RNA 1995-96 Richard J. Roberts* University of California, Santa Cruz 1996-97 Ronald M. Evans Santa Cruz, California 1998-99 Elizabeth H. Blackburn 1999-2000 Carl R. Woese and Norman R. Pace 2000-01 Willem P. C. Stemmer and Ronald W. Davis 2001-02 Janos K. Lanyi and Sir John E. Walker* 12:00 noon 2002-03 Peter B. -

Arthur Kornberg Discovered (The First) DNA Polymerase Four

Arthur Kornberg discovered (the first) DNA polymerase Using an “in vitro” system for DNA polymerase activity: 1. Grow E. coli 2. Break open cells 3. Prepare soluble extract 4. Fractionate extract to resolve different proteins from each other; repeat; repeat 5. Search for DNA polymerase activity using an biochemical assay: incorporate radioactive building blocks into DNA chains Four requirements of DNA-templated (DNA-dependent) DNA polymerases • single-stranded template • deoxyribonucleotides with 5’ triphosphate (dNTPs) • magnesium ions • annealed primer with 3’ OH Synthesis ONLY occurs in the 5’-3’ direction Fig 4-1 E. coli DNA polymerase I 5’-3’ polymerase activity Primer has a 3’-OH Incoming dNTP has a 5’ triphosphate Pyrophosphate (PP) is lost when dNMP adds to the chain E. coli DNA polymerase I: 3 separable enzyme activities in 3 protein domains 5’-3’ polymerase + 3’-5’ exonuclease = Klenow fragment N C 5’-3’ exonuclease Fig 4-3 E. coli DNA polymerase I 3’-5’ exonuclease Opposite polarity compared to polymerase: polymerase activity must stop to allow 3’-5’ exonuclease activity No dNTP can be re-made in reversed 3’-5’ direction: dNMP released by hydrolysis of phosphodiester backboneFig 4-4 Proof-reading (editing) of misincorporated 3’ dNMP by the 3’-5’ exonuclease Fidelity is accuracy of template-cognate dNTP selection. It depends on the polymerase active site structure and the balance of competing polymerase and exonuclease activities. A mismatch disfavors extension and favors the exonuclease.Fig 4-5 Superimposed structure of the Klenow fragment of DNA pol I with two different DNAs “Fingers” “Thumb” “Palm” red/orange helix: 3’ in red is elongating blue/cyan helix: 3’ in blue is getting edited Fig 4-6 E. -

Max Ferdinand Perutz 1914–2002

OBITUARY Max Ferdinand Perutz 1914–2002 Max Ferdinand Perutz, who died on in the MRC Laboratory of Molecular 6 February, will be remembered as Biology, which has grown to house one of the 20th century’s scientific over 400 people. He published over giants. Often referred to as the ‘fa- 100 papers and articles during his re- ther of molecular biology’, his work tirement. Once asked why he didn’t re- remains one of the foundations on tire at 65 he replied that he was tied up which science is being built today. in some very interesting research at Born in Vienna in 1914, Max was the time. Until the Friday before educated in the Theresianum, a Christmas, he was active in the lab al- grammar school originating from most every day, submitting his last an earlier Officers’ academy. His paper just a few days before then. parents suggested that he study law Max’s scientific interests ranged far to prepare for entering the family beyond medical research. As a sideline, business, but he chose to study he also worked on glaciers in his chemistry at the University of youth. He studied the transformation Vienna. of snowflakes that fall on glaciers into In 1936, with financial support the huge single ice crystals that make from his father, he began a PhD at the Cavendish up its bulk, and the relationship between the mechanical Laboratory in Cambridge. Using X-ray crystallography he properties of ice measured in the laboratory and the mecha- aimed to determine the structure of hemoglobin. But the nism of glacier flow. -

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY Theo James presenting a bouquet to HM The Queen on the occasion of her bicentenary visit, 7 December 1999. by Frank A.J.L. James The Director, Susan Greenfield, looks on Front page: Façade of the Royal Institution added in 1837. Watercolour by T.H. Shepherd or more than two hundred years the Royal Institution of Great The Royal Institution was founded at a meeting on 7 March 1799 at FBritain has been at the centre of scientific research and the the Soho Square house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph popularisation of science in this country. Within its walls some of the Banks (1743-1820). A list of fifty-eight names was read of gentlemen major scientific discoveries of the last two centuries have been made. who had agreed to contribute fifty guineas each to be a Proprietor of Chemists and physicists - such as Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday, a new John Tyndall, James Dewar, Lord Rayleigh, William Henry Bragg, INSTITUTION FOR DIFFUSING THE KNOWLEDGE, AND FACILITATING Henry Dale, Eric Rideal, William Lawrence Bragg and George Porter THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION, OF USEFUL MECHANICAL - carried out much of their major research here. The technological INVENTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS; AND FOR TEACHING, BY COURSES applications of some of this research has transformed the way we OF PHILOSOPHICAL LECTURES AND EXPERIMENTS, THE APPLICATION live. Furthermore, most of these scientists were first rate OF SCIENCE TO THE COMMON PURPOSES OF LIFE. communicators who were able to inspire their audiences with an appreciation of science. -

Obituary: Professor Arturo Falaschi the Human Frontier Science

Obituary: Professor Arturo Falaschi The Human Frontier Science Program Organization is greatly saddened by the sudden death of Prof. Arturo Falaschi on June 1st 2010. Arturo was a member of the HFSP Council of Scientists from 1996-2001, serving as Chair of the Council for two years from 2000-2001. This was a time of great change for HFSP following the appointment of Torsten Wiesel as Secretary General and the introduction of many program initiatives. Arturo led the discussions at the Council of Scientists with great energy and imagination. He contributed substantially to the transformation of HFSP that occurred during this period, being instrumental in the reorganization of the scientific programs by championing the merging of the traditional neuroscience and molecular biology committees. Arturo Falaschi had a distinguished scientific career in the field of DNA replication. After postdoctoral training with Nobel Laureates Har Gobind Khorana in Wisconsin and Arthur Kornberg at Stanford, he returned to Italy to the Institute of Genetics of the CNR (the Italian National Research Council) at the University of Pavia, where he was later appointed as Director of the CNR Institute for Biochemical and Evolutionary Genetics and then Director of the CNR National Project for Genetic Engineering. In 1987 he became Head of the Trieste component of the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB). From 1989-2004 he was Director-General of the ICGEB and remained associated with the Centre as Head of the ICGEB Molecular Biology Laboratory in Pisa. He also served as a member of the Executive Committee of the CNR. Arturo had a strong commitment to the global scientific endeavour.