Distributed Language Resources and Technology in a European Infrastructure

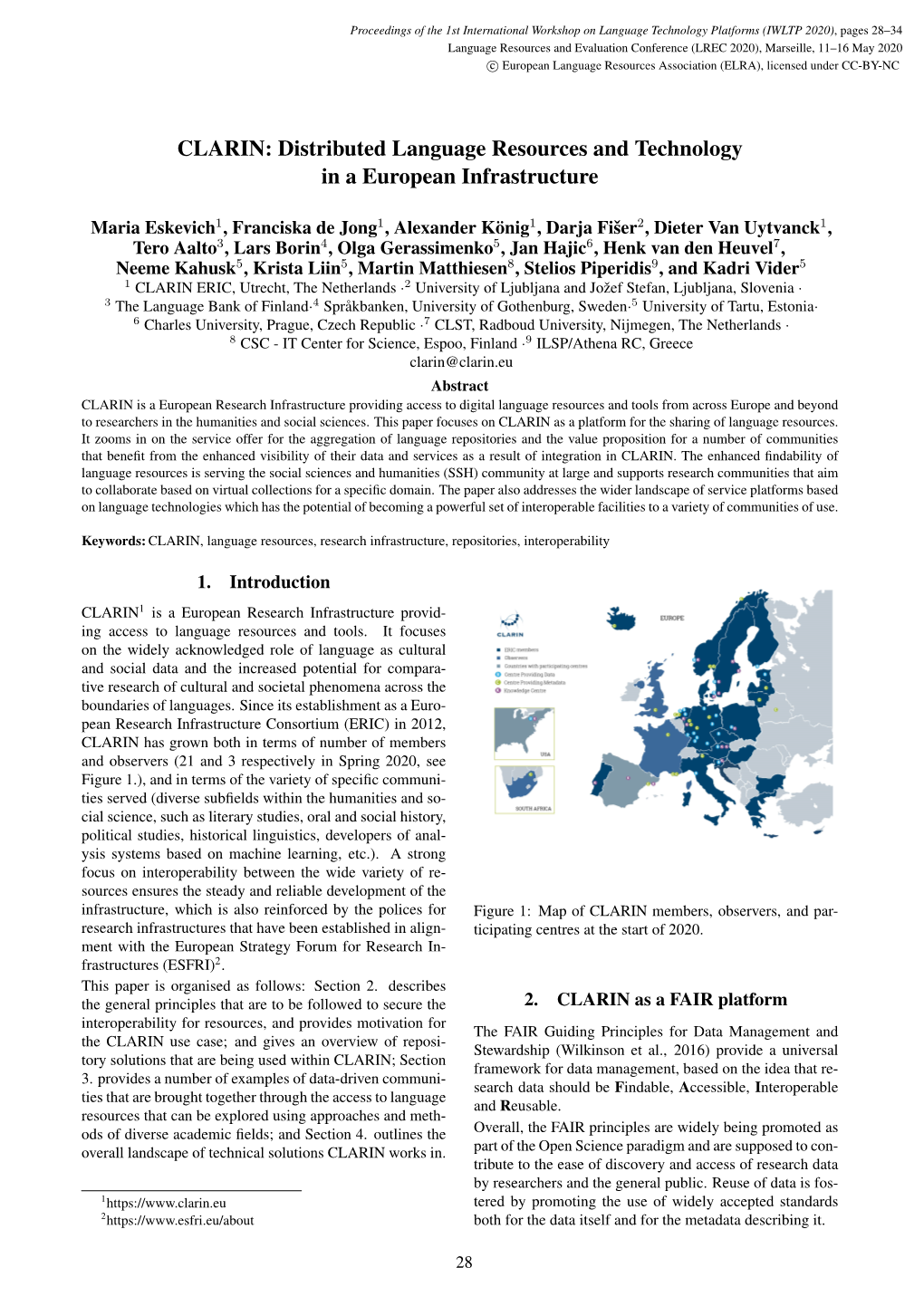

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report CLARIN Workshop DELAD: Database Enterprise for Language and Speech Disorders

Report CLARIN Workshop DELAD: Database Enterprise for Language And speech Disorders Date and location of the workshop The workshop took place as a lunch to lunch workshop on 28-30 January 2019 in room 3.1 at the SURF Offices, Hoog Overborch, Utrecht (https://www.surf.nl/en/about-surf/contact/directions-to-surf-surfmarket-and-surfnet/index.html ) For CLARIN this was a Type II workshop. The Organizing Team Henk van den Heuvel; CLST Radboud University, the Netherlands Satu Saalasti, University of Helsinki, Finland Martin Ball; Bangor University, UK Alice Lee; University College Cork, Ireland Nicole Müller; University College Cork, Ireland Aleksei Kelli; University of Tartu, Estonia 1 Information about the organizing team Dr Henk van den Heuvel has been involved in the collection, compilation and validation of many spoken and written language resources at the national and international level. He has been project leader and project participant in CLARIN-NL projects amongst which the VALID project (http://validdata.org/) which aimed to include a number of Dutch Corpora of Disordered Speech (CDS) in the CLARIN infrastructure. He is also co-coordinator of CLARIN-NL’s Data Curation Service now integrated into CLARIAH. Dr Satu Saalasti is a University Lecturer of Logopedics in the Department of Psychology and Logopedics at the University of Helsinki. Her research interests include multisensory perception of speech in individuals with autism spectrum disorders and neural mechanisms underlying real-life language. She has studied the brain mechanisms underlying lipreading, listening and reading in her post doctoral studies by combining functional magnetic resonance imaging and methods of computational linguistics. -

FIN-CLARIN and CLARIN

FIN-CLARIN and CLARIN Infrastructure for Digital Humanities Krister Lindén, National Coordinator of FIN-CLARIN CLARIN ERIC European Research Infrastructure Consortium • The Netherlands founded on February 29, 2012 • Austria • Bulgaria • Czech Republic CLARIN • Denmark • DLU www.clarin.eu / NL • Estonia • Finland Kielipankki / FIN-CLARIN • Germany • Greece Språkbanken / SWE-CLARIN • Hungary • Italy • Latvia IDS / CLARIN.DE • Lithuania • Norway • Poland • Portugal … • Slovenia • Sweden • France International cooperation NTU / Dutch CLARIN Center • UK and sharing of resources • USA / CMU 2 FIN-CLARIN partners www.kielipankki.fi: • University of Helsinki Coordinate the activity and provide access to large centrally acquired resources and tools • CSC – IT Center for Science • KOTUS – Institute for the Languages of Finland • Aalto University • University of Eastern Finland • University of Jyväskylä Provide access to resources and tools developed locally by individual researchers or • University of Oulu research groups • University of Tampere • University of Turku • University of Vaasa FIN-CLARIN Corpora for access or download Gw = billion words, Mw = million words, h = hours Resources 2017 2022 Text Magazines and newspapers 1770- (NLF and Web publ.) 12 Gw 20 Gw Social media and similar sources 2000- (Suomi24, Ylilauta, …) 4 Gw 10 Gw Literature and manuscripts (Gutenberg, Fennica, archives) 60 Mw 70 Mw Speech News broadcasts (YLE) 10000 h Currently, Video sessions from the Finnish Parliament 2008-2016 500 h 1000 h FIN-CLARIN has approx. 19 GW -

CLARIN: a Pan-European Research Infrastructure for Language Resources

CLARIN: a pan-European research infrastructure for language resources Martin Wynne [email protected] UCREL Seminar Lancaster Oxford e-Research Centre & Monday 23rd June 2014 IT Services (formerly OUCS) & Faculty of Linguistics, Philology and Phonetics, University of Oxford 1 Summary • Many areas of linguistics (and related disciplines) have been thoroughly transformed by digital data, tools and methods • Many areas of the humanities and social sciences are currently experiencing the digital turn (with great differences in the pace and impact of changes) • One aspect of the digital turn across is the introduction of digital language technologies and resources across a number of disciplines • There are numerous barriers to the successful deployment of these resources in real-life research scenarios • CLARIN is an attempt to address these problems and more fully realize the potential for the use of language resources (across the humanities and social sciences) • CLARIN is building the infrastructure to underpin, support and sustain research • Is there a way forward for CLARIN in the UK? 2 Corpus Linguistics 3 Interoperability and sustainability for digital textual scholarship Well-known problems with digital resources in the humanities of: • fragmentation of communities, resources, tools; • lack of connectness and interoperability; • sustainability of online services; • lack of deployment of tools as reliable and available services There is a potential solution in distributed, federated infrastructure services. 5 CLARIN in a nutshell -

Iassist Regional Report 2011-2012 European Region

IASSIST REGIONAL REPORT 2011‐2012 EUROPEAN REGION Iris Alfredsson, Swedish National Data Service (SND), May 30 2012 CROSS‐EUROPEAN COLLABORATIONS One of the main obstacles for the realisation of pan‐European Research Infrastructures has been the absence of a suitable legal and governance framework of European level. For this reason a new legal structure, ERIC – European Research Infrastructure Consortium” was developed by the European Commission together with ESFRI, the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures in 2009. Five European research infrastructures within the social science and the humanities – CESSDA, CLARIN, DARIAH, ESS and SHARE ‐ are currently in the process of becoming, or has recently become, an ERIC. CESSDA – COUNCIL OF EUROPEAN SOCIAL SCIENCE DATA ARCHIVES The 2011 CESSDA Expert Seminar was held in October at FORS in Lausanne, Switzerland. 21 persons from 12 countries attended the seminar on the topic of Question Data Banks. The 2012 General Assembly was held in April at SND in Gothenburg, Sweden. At the meeting a new CESSDA member was welcomed, the Lithuanian Data Archive for Social Science and Humanities (LiDA), based in Kaunas. In 2012, CESSDA will focus on becoming an ERIC. The General Assembly decided to launch a self‐evaluation project of all the member archives. The structured self‐evaluations will provide information on how the CESSDA members meet the requirements of the CESSDA‐ERIC Statutes, and which members need advice and support on various parts of the activities. Twelve European countries have signed the Memorandum of Understanding to commit their financial and political support for the setting up of a CESSDA ERIC. -

A Brief History of Archiving in Language Documentation, with an Annotated Bibliography

Vol. 10 (2016), pp. 411–457 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24714 Revised Version Received: 19 April 2016 Series: Emergent Use and Conceptualization of Language Archives Michael Alvarez Shepard, Gary Holton & Ryan Henke (eds.) A Brief History of Archiving in Language Documentation, with an Annotated Bibliography Ryan E. Henke University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Andrea L. Berez-Kroeker University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa We survey the history of practices, theories, and trends in archiving for the pur- poses of language documentation and endangered language conservation. We identify four major periods in the history of such archiving. First, a period from before the time of Boas and Sapir until the early 1990s, in which analog materials were collected and deposited into physical repositories that were not easily acces- sible to many researchers or speaker communities. A second period began in the 1990s, when increased attention to language endangerment and the development of modern documentary linguistics engendered a renewed and redefined focus on archiving and an embrace of digital technology. A third period took shape in the early twenty-first century, where technological advancements and efforts to develop standards of practice met with important critiques. Finally, in the cur- rent period, conversations have arisen toward participatory models for archiving, which break traditional boundaries to expand the audiences and uses for archives while involving speaker communities directly in the archival process. Following the article, we provide an annotated bibliography of 85 publications from the literature surrounding archiving in documentary linguistics. This bibliography contains cornerstone contributions to theory and practice, and it also includes pieces that embody conversations representative of particular historical periods. -

Attachment 1 – Proposal of the Project of Large Infrastructure Approved by the Government

Attachment 1 – Proposal of the Project of large infrastructure approved by the Government LINDAT/CLARIN Project Establishing and operating the Czech node of pan-European infrastructure for research The applicant The Charles University in Prague is the applicant, however, the Institute of Formal and Applied Linguistics of Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, will administer the funds. The Charles University in Prague will ensure in accordance to bilateral contracts a transfer of the funds necessary for operating the Clarin central node and for performing the national tasks at the workplaces which will contribute to the project based on the approved budget. In addition to it, the Charles University in Prague will provide for (if it is not otherwise decided so far) the transfer of scheduled resources to future Clarin-ERIC associations. A person responsible for organisational, technical and personnel management of the project (principal investigator): Prof. RNDr. Jan Hajič, Dr. ( [email protected] ), The Head of the Institute of Formal and Applied Linguistics, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University in Prague, Malostranské nám. 25, 11800 Praha 1 (phone: +420 607 209 212). The Institute of Formal and Applied Linguistics, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University in Prague ( http://ufal.mff.cuni.cz ) is a leading national centre in the field of computer processing of natural language which has been developed in the framework of research centre programmes and research tasks, holding an outstanding international position in existing pan-European projects. The planned project of the research infrastructure directly follows the CLARIN (FP7-RI-2122230) project. -

GREEK-BERT: the Greeks Visiting Sesame Street

GREEK-BERT: The Greeks visiting Sesame Street John Koutsikakis∗ Ilias Chalkidis∗ Prodromos Malakasiotis Ion Androutsopoulos [jkoutsikakis,ihalk,rulller,ion]@aueb.gr Department of Informatics, Athens University of Economics and Business ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION Transformer-based language models, such as BERT and its variants, Natural Language Processing (NLP) has entered its ImageNet [9] have achieved state-of-the-art performance in several downstream era as advances in transfer learning have pushed the limits of natural language processing (NLP) tasks on generic benchmark the field in the last two years [32]. Pre-trained language mod- datasets (e.g., GLUE, SQUAD, RACE). However, these models have els based on Transformers [33], such as BERT [10] and its vari- mostly been applied to the resource-rich English language. In this ants [20, 21, 38], have achieved state-of-the-art results in several paper, we present GREEK-BERT, a monolingual BERT-based lan- downstream NLP tasks (e.g., text classification, natural language guage model for modern Greek. We evaluate its performance in inference) on generic benchmark datasets, such as GLUE [35], three NLP tasks, i.e., part-of-speech tagging, named entity recog- SQUAD [31], and RACE [17]. However, these models have mostly nition, and natural language inference, obtaining state-of-the-art targeted the English language, for which vast amounts of data performance. Interestingly, in two of the benchmarks GREEK-BERT are readily available. Recently, multilingual language models (e.g., outperforms two multilingual Transformer-based models (M-BERT, M-BERT, XLM, XLM-R) have been proposed [3, 7, 18] covering XLM-R), as well as shallower neural baselines operating on pre- multiple languages, including modern Greek. -

Czech Republic Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure

Tour de CLARIN CLARIN Czech Republic Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure Written by Barbora Hladka, Darja Fišer and Jakob Lenardič, and edited by Darja Fišer and Jakob Lenardič Foreword Tour de CLARIN highlights prominent user involvement activities of CLARIN national consortia with the aim to increase the visibility of CLARIN consortia, reveal the richness of the CLARIN landscape, and display the full range of activities throughout the CLARIN network that can inform and inspire other consortia as well as show what CLARIN has to offer to researchers, teachers, students, professionals and the general public interested in using and processing language data in various forms. This brochure presents Czech Republic and is organized in five sections: • Section One presents the members of the consortium and their work • Section Two demonstrates an outstanding tool • Section Three highlights a prominent resource • Section Four reports on a successful event for researchers and students • Section Five includes an interview with a renowned researcher from the digital humanities or social sciences who has successfully used the consortium’s infrastructure in their research FOREWORD 3 Prague, Czech Republic | photo by Rodrigo Ardilha | Unsplash Czech Republic LINDAT Team | Back row: Pavel Straňák, Jaroslava Hlaváčová, Pavel Pecina, David Mareček, Ondřej Bojar, Jan Hajič, Milan Written by Darja Fišer and Jakob Lenardič Fučík. Front row: Barbora Hladká, Anna Nedoluzhko, Vendula Kettnerová, Eva Hajičová (national coordinator), Anna -

Kielipankki – As Open As Possible

Kielipankki – as open as possible Mietta Lennes, FIN-CLARIN [email protected] https://www.kielipankki.fi 25.3.2021 www.kielipankki.fi 2 Users of the Language Bank • Researchers from all fields welcome! • Many corpora are available even without signing in. • FIN-CLARIN can help you in storing and distributing your own corpus. Member countries (21): Austria CLARIN ERIC Bulgaria Croatia European Research Infrastructure Consortium Cyprus Czech Republic founded on February 29, 2012 Denmark https://www.clarin.eu / NL Estonia Finland Germany Greece Hungary Iceland Italy Latvia Lithuania The Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Slovenia Sweden Observers (3): [ … ] France South Africa International cooperation United Kingdom and sharing of resources Third party (1): for Humanities and Social Sciences CMU (USA) Updated: 24.3.2021 CLARIN centres Member countries (21): Austria Bulgaria Croatia Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Estonia Finland Germany Greece Hungary Iceland Italy Latvia Lithuania The Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Slovenia Sweden Observers (3): France South Africa United Kingdom Third party (1): CMU (USA) Updated: 24.3.2021 www.kielipankki.fi What kind of data can be deposited? • Text or speech in any natural language – text documents, audio and video recordings – annotations and transcripts may be included – must be in useful and well-described formats • Make sure you have the rights to distribute the data, at least for research purposes – Copyrights – Personal data Contact FIN-CLARIN for details [email protected] Plenary -

Towards an Open Science Infrastructure for the Digital Humanities: the Case of CLARIN

Towards an Open Science Infrastructure for the Digital Humanities: The Case of CLARIN 1 2 3 4 Koenraad De Smedt , Franciska de Jong , Bente Maegaard , Darja Fišer and Dieter Van Uytvanck5 1 University of Bergen, Norway 2,5 CLARIN ERIC, The Netherlands 3 University of Copenhagen, Denmark 4 University of Ljubljana and Jožef Stefan Institute, Slovenia [email protected] Abstract. CLARIN is the European research infrastructure for language resources. It is a sustainable home for digital research data in the humanities and it also offers tools and services for annotation, analysis and modeling. The scope and structure of CLARIN enable a wide range of studies and approaches, including comparative studies across regions, periods, languages and cultures. CLARIN does not see itself as a stand-alone facility, but rather as a player in making the vision that is underlying the emerging European policies towards Open Science a reality, by interconnecting researchers across national and discipline borders and by offering seamless access to data and services in line with the FAIR data principles. CLARIN also aims to contribute to responsible data science by the design as well as the governance of its infrastructure and to achieve an appropriate and transparent division of responsibilities between data providers, technical centres, and end users. CLARIN offers training towards digital scholarship for humanities scholars and aims at increased uptake from this audience. Keywords: CLARIN, Research Infrastructure, Language Resources and Technologies. 1 Introduction CLARIN, the European research infrastructure for language resources, provides access to digital language resources and tools through a single sign-on environment with the aim to support researchers in the humanities and social sciences and related fields. -

GRUPO CLARIN S.A. Offering of 50,000,000 Class B Common Shares in the Form of Class B Shares and Global Depository Shares

GRUPO CLARIN S.A. Offering of 50,000,000 Class B Common Shares in the form of Class B Shares and Global Depository Shares This offering circular (the “Offering Circular”) relates to a global offering (the “Offering”) by Grupo Clarín S.A. (“Grupo Clarín” or the “Company”), a sociedad anónima organised under the laws of Argentina, and the selling shareholders named in this Offering Circular (the “Selling Shareholders”) of 50,000,000 class B common shares of the Company, with nominal value of one (1) Peso (as defined herein) and one vote per share, and with rights to dividends equal to those of the other outstanding shares of the Company. Of the class B common shares being offered, the Company is selling 15,000,000 class B common shares (the “New Shares”) and the Selling Shareholders are selling 35,000,000 class B common shares (the “Selling Shareholder Shares” and together with the New Shares, the “Class B Shares”). The Company will not receive any proceeds from the sale of the Selling Shareholder Shares. As part of the Offering, the Company and the Selling Shareholders are offering Class B Shares, in the form of global depositary shares (“GDSs” and, together with the Class B Shares, the “Securities”) evidenced by global depositary receipts (“GDRs”) in the United States of America (the “United States”) and other countries outside Argentina through the international underwriters named in this Offering Circular. Each GDS represents two Class B Shares. The Company is offering 3,500,000 New Shares in the form of 1,750,000 GDSs in the United States and other countries outside Argentina through the international underwriters named in this Offering Circular. -

Conference Programme

EURO MED 2 - 5 11 2020 20 EUROPEAN-MEDITERRANEAN CONFERENCE 2020 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... 1 PUBLICATIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 2 COMMITTEE .................................................................................................................................................. 7 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS ....................................................................................................................................... 9 EU PROJECTS & CHAIRS .................................................................................................................................27 RESEARCH INFRASTRUCTURES .................................................................................................................32 INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS ...........................................................................................................33 WORKSHOPS.................................................................................................................................................35 Workshop1 - The 2nd EU Workshop on how digital technologies can contribute to the preservation and restoration of Europe's most important and endangered Cultural Heritage sites. ...................................35 Workshop2 - The 5th International