Nsw Public Health Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Health Unit – Referral List at July 2020 Postcode PHU Postcode PHU Postcode PHU PHU Details

Public Health Unit – Referral List at July 2020 Postcode PHU Postcode PHU Postcode PHU PHU Details Albury PHU (Murrumbidgee & Southern NSW LHD ) 2000-2002 Randwick PHU 2379-2382 Tamworth PHU 2717 Broken Hill PHU PO Box 3095, Albury NSW 2640 2004-2009 Camperdown PHU 2386-2390 Tamworth PHU 2720 Albury PHU Phone: (02) 6080 8900 Fax: (02) 6933 9220 (secure) 2010-2011 Randwick PHU 2395-2396 Dubbo PHU 2721 Bathurst PHU Bathurst PHU (Far West & Western NSW LHD) PO Box 143, Bathurst NSW 2795 2012-2017 Camperdown PHU 2397-2411 Tamworth PHU 2722 Albury PHU Phone: (02) 6330 5880 Fax: (02) 6332 3137 (secure) 2018-2036 Randwick PHU 2415 Newcastle PHU 2725 Albury PHU Broken Hill PHU (Far West & Western NSW LHD) PO Box 457, Broken Hill NSW 2880 2037-2050 Camperdown PHU 2420-2430 Newcastle PHU 2726 Goulburn PHU Phone: (08) 8080 1420 Fax: (08) 8080 1196 (secure) 2052 Randwick PHU 2431 Port Macquarie PHU 2727-2733 Albury PHU Camperdown PHU (Sydney LHD) 2055-2114 Hornsby PHU 2439-2456 Port Macquarie PHU 2734 Broken Hill PHU PO Box 374 Camperdown NSW 1450 Phone: (02) 9515 9420 Fax: (02) 9515 9467 (secure) 2115-2118 Parramatta PHU 2460-2466 Lismore PHU 2735-2736 Albury PHU Dubbo PHU (Far West & Western NSW LHD) 2119-2122 Hornsby PHU 2469-2474 Lismore PHU 2737-2739 Broken Hill PHU PO Box 4061, Dubbo NSW 2830 2123-2125 Parramatta PHU 2475 Tamworth PHU 2745 Penrith PHU Phone: (02) 6809 8979 Fax: (02) 6809 7963 (secure) Gosford PHU (Central Coast LHD) 2126 Hornsby PHU 2476-2490 Lismore PHU 2747-2751 Penrith PHU PO Box 361, Gosford NSW 2250 2127-2128 Parramatta -

Broken Hill Complex

Broken Hill Complex Bioregion resources Photo Mulyangarie, DEH Broken Hill Complex The Broken Hill Complex bioregion is located in western New South Wales and eastern South Australia, spanning the NSW-SA border. It includes all of the Barrier Ranges and covers a huge area of nearly 5.7 million hectares with approximately 33% falling in South Australia! It has an arid climate with dry hot summers and mild winters. The average rainfall is 222mm per year, with slightly more rainfall occurring in summer. The bioregion is rich with Aboriginal cultural history, with numerous archaeological sites of significance. Biodiversity and habitat The bioregion consists of low ranges, and gently rounded hills and depressions. The main vegetation types are chenopod and samphire shrublands; casuarina forests and woodlands and acacia shrublands. Threatened animal species include the Yellow-footed Rock- wallaby and Australian Bustard. Grazing, mining and wood collection for over 100 years has led to a decline in understory plant species and cover, affecting ground nesting birds and ground feeding insectivores. 2 | Broken Hill Complex Photo by Francisco Facelli Broken Hill Complex Threats Threats to the Broken Hill Complex bioregion and its dependent species include: For Further information • erosion and degradation caused by overgrazing by sheep, To get involved or for more information please cattle, goats, rabbits and macropods phone your nearest Natural Resources Centre or • competition and predation by feral animals such as rabbits, visit www.naturalresources.sa.gov.au -

Listing and Sitting Arrangements, Nsw Local Court

LISTING AND SITTING ARRANGEMENTS, NSW LOCAL COURT Listing and sitting arrangements of the NSW Local Court Click on the links below to find the listing and sitting arrangements for each court. CHAMBER DAYS – Please note that Chamber Days have been cancelled from August 2020 to March 2021 to allow for the listing of defended work Albion Park Broken Hill Deniliquin Albury Burwood Downing Centre Armidale Byron Bay Dubbo Assessors - Small Claims Camden Dunedoo Ballina Campbelltown Dungog Bankstown Campbelltown Children's Eden Batemans Bay Casino Fairfield Bathurst Central Finley Bega Cessnock Forbes Bellingen Cobar Forster Belmont Coffs Harbour Gilgandra Bidura Children's Court Commonwealth Matters - Glen Innes (Glebe) (see Surry Hills see Downing Centre Gloucester Children’s Court) Condobolin Gosford Blayney Cooma Goulburn Blacktown Coonabarabran Grafton Boggabilla Coonamble Grenfell Bombala Cootamundra Griffith Bourke Corowa Gulgong Brewarrina Cowra Broadmeadow Children's Gundagai Crookwell Court Circuits Gunnedah 1 LISTING AND SITTING ARRANGEMENTS, NSW LOCAL COURT Hay Manly Nyngan Hillston Mid North Coast Children’s Oberon Court Circuit Holbrook Orange Milton Hornsby Parkes Moama Hunter Children’s Court Parramatta Circuit Moree Parramatta Children’s Court Illawarra Children's Court Moruya Peak Hill (Nowra, Pt. Kembla, Moss Moss Vale Vale and Goulburn) Penrith Mt Druitt Inverell Picton Moulamein Junee Port Kembla Mudgee Katoomba Port Macquarie Mullumbimby Kempsey Queanbeyan Mungindi Kiama Quirindi Murrurundi Kurri Kurri Raymond Terrace Murwillumbah -

Outback NSW Regional

TO QUILPIE 485km, A THARGOMINDAH 289km B C D E TO CUNNAMULLA 136km F TO CUNNAMULLA 75km G H I J TO ST GEORGE 44km K Source: © DEPARTMENT OF LANDS Nindigully PANORAMA AVENUE BATHURST 2795 29º00'S Olive Downs 141º00'E 142º00'E www.lands.nsw.gov.au 143º00'E 144º00'E 145º00'E 146º00'E 147º00'E 148º00'E 149º00'E 85 Campground MITCHELL Cameron 61 © Copyright LANDS & Cartoscope Pty Ltd Corner CURRAWINYA Bungunya NAT PK Talwood Dog Fence Dirranbandi (locality) STURT NAT PK Dunwinnie (locality) 0 20 40 60 Boonangar Hungerford Daymar Crossing 405km BRISBANE Kilometres Thallon 75 New QUEENSLAND TO 48km, GOONDIWINDI 80 (locality) 1 Waka England Barringun CULGOA Kunopia 1 Region (locality) FLOODPLAIN 66 NAT PK Boomi Index to adjoining Map Jobs Gate Lake 44 Cartoscope maps Dead Horse 38 Hebel Bokhara Gully Campground CULGOA 19 Tibooburra NAT PK Caloona (locality) 74 Outback Mungindi Dolgelly Mount Wood NSW Map Dubbo River Goodooga Angledool (locality) Bore CORNER 54 Campground Neeworra LEDKNAPPER 40 COUNTRY Region NEW SOUTH WALES (locality) Enngonia NAT RES Weilmoringle STORE Riverina Map 96 Bengerang Check at store for River 122 supply of fuel Region Garah 106 Mungunyah Gundabloui Map (locality) Crossing 44 Milparinka (locality) Fordetail VISIT HISTORIC see Map 11 elec 181 Wanaaring Lednapper Moppin MILPARINKA Lightning Ridge (locality) 79 Crossing Coocoran 103km (locality) 74 Lake 7 Lightning Ridge 30º00'S 76 (locality) Ashley 97 Bore Bath Collymongle 133 TO GOONDIWINDI Birrie (locality) 2 Collerina NARRAN Collarenebri Bullarah 2 (locality) LAKE 36 NOCOLECHE (locality) Salt 71 NAT RES 9 150º00'E NAT RES Pokataroo 38 Lake GWYDIR HWY Grave of 52 MOREE Eliza Kennedy Unsealed roads on 194 (locality) Cumborah 61 Poison Gate Telleraga this map can be difficult (locality) 120km Pincally in wet conditions HWY 82 46 Merrywinebone Swamp 29 Largest Grain (locality) Hollow TO INVERELL 37 98 For detail Silo in Sth. -

Your Complete Guide to Broken Hill and The

YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO DESTINATION BROKEN HILL Mundi Mundi Plains Broken Hill 2 City Map 4–7 Getting There and Around 8 HistoriC Lustre 10 Explore & Discover 14 Take a Walk... 20 Arts & Culture 28 Eat & Drink 36 Silverton Places to Stay 42 Shopping 48 Silverton prospects 50 Corner Country 54 The Outback & National Parks 58 Touring RoutEs 66 Regional Map 80 Broken Hill is on Australian Living Desert State Park Central Standard Time so make Line of Lode Miners Memorial sure you adjust your clocks to suit. « Have a safe and happy journey! Your feedback about this guide is encouraged. Every endeavour has been made to ensure that the details appearing in this publication are correct at the time of printing, but we can accept no responsibility for inaccuracies. Photography has been provided by Broken Hill City Council, Destination NSW, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, Simon Bayliss, The Nomad Company, Silverton Photography Gallery and other contributors. This visitor guide has been designed by Gang Gang Graphics and produced by Pace Advertising Pty. Ltd. ABN 44 005 361 768 Tel 03 5273 4777 W pace.com.au E [email protected] Copyright 2020 Destination Broken Hill. 1 Looking out from the Line Declared Australia’s first heritage-listed of Lode Miners Memorial city in 2015, its physical and natural charm is compelling, but you’ll soon discover what the locals have always known – that Broken Hill’s greatest asset is its people. Its isolation in a breathtakingly spectacular, rugged and harsh terrain means people who live here are resilient and have a robust sense of community – they embrace life, are self-sufficient and make things happen, but Broken Hill’s unique they’ve always got time for each other and if you’re from Welcome to out of town, it doesn’t take long to be embraced in the blend of Aboriginal and city’s characteristic old-world hospitality. -

424 5328 Vice President Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 State Secretary Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 State Treasurer Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034

TASMANIAN FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY INC. PO Box 191 Launceston Tasmania 7250 State Secretary: [email protected] Journal Editors: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.tasfhs.org Patron: Dr Alison Alexander Fellows: Neil Chick, David Harris and Denise McNeice Executive: President Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Vice President David Harris (03) 6424 5328 Vice President Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 State Secretary Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 State Treasurer Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Committee: Judy Cocker Peter Cocker Elaine Garwood Isobel Harris John Gillham Libby Gillham Brian Hortle Leo Prior Helen Stuart Judith Whish-Wilson By-laws Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Assistant By-laws Officer David Harris (03) 6424 5328 Webmaster Robert Tanner (03) 6231 0794 Journal Editors Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 LWFHA Coordinator Judith De Jong (03) 6327 3917 Members’ Interests Compiler John Gillham (03) 6239 6529 Membership Registrar Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Publications Coordinator Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Public Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Reg Gen BDM Liaison Officer Colleen Read (03) 6244 4527 State Sales Officer Mrs Pat Harris (03) 6344 3951 Branches of the Society Burnie: PO Box 748 Burnie Tasmania 7320 [email protected] Devonport: PO Box 587 Devonport Tasmania 7310 [email protected] Hobart: PO Box 326 Rosny Park Tasmania 7018 [email protected] Huon: PO Box 117 Huonville Tasmania 7109 [email protected] Launceston: PO Box 1290 Launceston Tasmania 7250 [email protected] Volume 26 Number 4 March 2006 ISSN 0159 0677 Contents Editorial ............................................................................................................ 218 President’s Message ....................................................................................... -

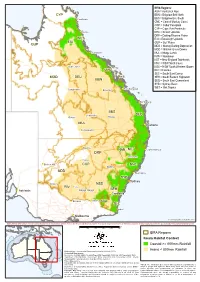

Koala Context

IBRA Regions: AUA = Australian Alps CYP BBN = Brigalow Belt North )" Cooktown BBS = Brigalow Belt South CMC = Central Mackay Coast COP = Cobar Peneplain CYP = Cape York Peninsula ") Cairns DEU = Desert Uplands DRP = Darling Riverine Plains WET EIU = Einasleigh Uplands EIU GUP = Gulf Plains GUP MDD = Murray Darling Depression MGD = Mitchell Grass Downs ") Townsville MUL = Mulga Lands NAN = Nandewar NET = New England Tablelands NNC = NSW North Coast )" Hughenden NSS = NSW South Western Slopes ") CMC RIV = Riverina SEC = South East Corner MGD DEU SEH = South Eastern Highlands BBN SEQ = South East Queensland SYB = Sydney Basin ") WET = Wet Tropics )" Rockhampton Longreach ") Emerald ") Bundaberg BBS )" Charleville )" SEQ )" Quilpie Roma MUL ") Brisbane )" Cunnamulla )" Bourke NAN NET ") Coffs Harbour DRP ") Tamworth )" Cobar ") Broken Hill COP NNC ") Dubbo MDD ") Newcastle SYB ") Sydney ") Mildura NSS RIV )" Hay ") Wagga Wagga SEH Adelaide ") ") Canberra ") ") Echuca Albury AUA SEC )" Eden ") Melbourne © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 INDICATIVE MAP ONLY: For the latest departmental information, please refer to the Protected Matters Search Tool and the Species Profiles & Threats Database at http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/index.html km 0 100 200 300 400 500 IBRA Regions Koala Habitat Context Coastal >= 800mm Rainfall Produced by: Environmental Resources Information Network (2014) Inland < 800mm Rainfall Contextual data source: Geoscience Australia (2006), Geodata Topo 250K Topographic Data and 10M Topographic Data. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2012). Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA), Version 7. Other data sources: Commonwealth of Australia, Bureau of Meteorology (2003). Mean annual rainfall (30-year period 1961-1990). Caveat: The information presented in this map has been provided by a Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2013). -

The Railway Line to Broken Hill

RAILS TO THE BARRIER Broken Hill as seen from the top of the line of Lode. The 1957 station is in the right foreground. Image: Gary Hughes ESSAYS TO COMMEMORATE THE CENTENARY OF THE NSW RAILWAY SERVING BROKEN HILL. Australian Railway Historical Society NSW Division. July 2019. 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................ 3 HISTORY OF BROKEN HILL......................................................................... 5 THE MINES................................................................................................ 7 PLACE NAMES........................................................................................... 9 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE....................................................................... 12 CULTURE IN THE BUILDINGS...................................................................... 20 THE 1919 BROKEN HILL STATION............................................................... 31 MT GIPPS STATION.................................................................................... 77 MENINDEE STATION.................................................................................. 85 THE 1957 BROKEN HILL STATION................................................................ 98 SULPHIDE STREET STATION........................................................................ 125 TARRAWINGEE TRAMWAY......................................................................... 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................... -

7 Day Lake Eyre Tour

7 Day Lake Eyre Tour Contact us today to arrange pick-ups from your regional town! Day 1. Thursday 13th June 2019 - Dubbo - Broken Hill Join us as we depart Dubbo at 6.00am, travelling via Nyngan and Cobar with a lunch stop along the Barrier Highway. We will arrive late afternoon in Broken Hill for our first nights accommodation. Day 2. Friday 14th June 2019 - Broken Hill—Leigh Creek Departing Broken Hill we continue along the Barrier Highway leaving NSW behind. Enjoy staying in Leigh Creek for the night. Day 3. Saturday 15th June 2019 - Leigh Creek– Marree This morning you have free time to explore Leigh Creek at your own pace before heading to Marree. Day 4. Sunday 16th June 2019 - Marree Today we have a unique opportunity to enjoy a scenic flight over Lake Eyre, Marree Man, the Dingo Fence and much more in this stunning painted desert. Day 5. Monday 17th June 2019 - Marree- Port Augusta This morning we travel via Farina, Hawker and Pichi Richie Railway to Port Augusta for our overnight stop. Day 6. Tuesday 18th June 2019 - Port Augusta– Broken Hill We depart Port Augusta travelling on the Stuart Highway, stopping at the Peterborough Rail Museum. Your accommodation tonight is in Broken Hill. Day 7. Wednesday 19th June 2019 - Broken Hill– Dubbo $2,900 Per Person Twin Share Today is your final day. We depart Broken Hill and arrive in Dubbo late afternoon. $3,150 Per Person Single Traveller THIS PACKAGE INCLUDES THE FOLLOWING: $550 deposit per person required on booking Dinner, bed and breakfast each day Final payment due Friday 31st May 2019 Flight with stunning views over Lake Eyre All coach travel and transfers, in a fully air conditioned, restroom equipped coach *Deposit is non refundable as it is required to purchase your flight tickets. -

A Regional Geophysical Study of the Broken Hill Block, N.S.W., Àustràlia

t -", oùttt l lVw QI\c JHnitrereitg cf .Aleluile pr:purtrnant of pccnomic (6eologg A REGIONAL GEOPHYSICAL STUDY OF THE BROKEN HILL BLOCK, N.S.W., ÀUSTRÀLIA David J. Isles B.Sc. (Hons) Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Economic GeologYr Faculty of Science The University of Adelaide' 1983 BROK EN¡ [.{ILL REüIOI{ (coun of BþIP} o[oun lmuge of Bf{R aetrornagnehie dmhn 0 füil STATEMENT To the best of the writerrs knowJ-edge and belief, and except where reference is made herein, this thesis contains no copy or paraphrase of previously published material nor any material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any University. DAVID ISLES JuIy 1983 Ac knowledgements This project was carried out by the author under the supervision of Professor D.M. Boyd. Professor Boydrs enthusiasm for the project and his astute guidance are gratefully acknowledged. Mr. J.I. Mclntyre and Dr. D. Atchuta Rao contributeci greatly to this work with fruitful- discussions, suggestions and encouragement. The Broken HiIr Mining Managerrs Association supported the field work associated with the project. The Bureau of Mineral Resources and the NSW Geological Survey contributed digital data and unpuþIished maps. The Broken HilI Proprietary Company assisted in the preparation of the text and diagrams. I wish to thank Dr. P.I. Brooker, ME. R.J. Smith and Mr. P. G. Harman for support and encouragement during critical- stages of the project; Ms. Sharon Prof eres and I{r. Evert BJ-eys f or drafting and photographic work respectively; Mr. -

The Farrer Flier

Mental health moves towards MAY2016.issue33 individualised care packages Grants for Sporting Schools The Australian Government’s $100million Sporting School’s programme is now just on 12 Between four and five million Australians Under this package people, identified by months old - and I am delighted that more than FLIER suffer some form of mental health issue in health professionals as needing complex care sixty schools and communities across Farrer THE FARRER any one given year, making it ranked the third services, are eligible to access integrated have registered for the programme. largest chronic disease in the country. health services, including comprehensive We know parents live busy lives and we know assessment and care-coordination support; Now, as part of bold new reforms, Australians that finding the time to schedule in sport for psychological services; mental health With the electorate redistribution announced earlier in the year, this will be the first (hopefully of many) of my fliers received in areas including with a severe and complex mental illness will children is sometimes really challenging. In nursing; drug and alcohol services; vocational Griffith, Coleambally, Leeton, Narrandera and Hillston. To the shires of Murrumbidgee, Leeton, Carrathool and Narrandera and Griffith City - have access to an integrated care package response to that, Sporting Schools has been assistance; and peer support. welcome to Farrer! tailored to their individual needs. designed to get more children fit, healthy The arrangements are to be phased in over Just like any other chronic disease, mental and involved in sport earlier in life, while also I am excited to get to know these new areas and the people who help make them so special. -

Queensland Geological Framework

Geological framework (Compiled by I.W. Withnall & L.C. Cranfield) The geological framework outlined here provides a basic overview of the geology of Queensland and draws particularly on work completed by Geoscience Australia and the Geological Survey of Queensland. Queensland contains mineralisation in rocks as old as Proterozoic (~1880Ma) and in Holocene sediments, with world-class mineral deposits as diverse as Proterozoic sediment-hosted base metals and Holocene age dune silica sand. Potential exists for significant mineral discoveries in a range of deposit styles, particularly from exploration under Mesozoic age shallow sedimentary cover fringing prospective older terranes. The geology of Queensland is divided into three main structural divisions: the Proterozoic North Australian Craton in the north-west and north, the Paleozoic–Mesozoic Tasman Orogen (including the intracratonic Permian to Triassic Bowen and Galilee Basins) in the east, and overlapping Mesozoic rocks of the Great Australian Basin (Figure 1). The structural framework of Queensland has recently been revised in conjunction with production of a new 1:2 million-scale geological map of Queensland (Geological Survey of Queensland, 2012), and also the volume on the geology of Queensland (Withnall & others, 2013). In some cases the divisions have been renamed. Because updating of records in the Mineral Occurrence database—and therefore the data sheets that accompany this product—has not been completed, the old nomenclature as shown in Figure 1 is retained here, but the changes are indicated in the discussion below. North Australian Craton Proterozoic rocks crop out in north-west Queensland in the Mount Isa Province as well as the McArthur and South Nicholson Basins and in the north as the Etheridge Province in the Georgetown, Yambo and Coen Inliers and Savannah Province in the Coen Inlier.