Agenda for UNFF Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title SNARE HUNTING AMONG BAKA HUNTER- GATHERERS

SNARE HUNTING AMONG BAKA HUNTER- Title GATHERERS : IMPLICATIONS FOR SUSTAINABLE WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT Author(s) YASUOKA, Hirokazu African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2014), 49: Citation 115-136 Issue Date 2014-08 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/189625 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 49: 115–136, August 2014 115 SNARE HUNTING AMONG BAKA HUNTER-GATHERERS: IMPLICATIONS FOR SUSTAINABLE WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT Hirokazu YASUOKA Faculty of Humanity and Environment, Hosei University ABSTRACT Diversity in hunting methods has been reported among the Mbuti net hunters in Ituri in northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, among the Baka hunters in southeastern Cameroon, who currently practice snare hunting as their principal method, and among other hunter-gatherers in central African forests. Although forest duikers are the main targets of all of these hunters, different species of duikers are captured by different methods. Blue duikers (Philantomba monticola) weighing about 4–5 kg comprise the majority of the Mbuti’s net-hunting harvests, whereas red duikers (in particular, Cephalophus callipygus and C. dorsalis) weighing about 15–20 kg are the major catch in Baka snare hunting. The density of duikers in each area is reflected in the rate of captures: the density of blue duikers is higher in the forests used by Mbuti net hunters, and red duikers are more abundant in the Baka area. Thus, it is likely that the relative abundance of each species is one of the major contributors to the selection of an efficient hunting method. Indeed, non-traditional methods may be selected as a result of adaptation to ecological conditions, the availability of hunting tools, and the changing role of hunting in the livelihoods of hunters. -

1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of International

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of International Conservation Africa Regional Program FY 2016 Summary of Projects In FY 2016, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) awarded funding to 37 projects totaling $16,129,729 through the Africa Regional Program, which was matched by $25,124,875 in additional leveraged funds. Unless otherwise noted, all projects were funded through the Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE). Field projects in seven countries (in alphabetical order below) and 10 projects across multiple countries were supported. New Multi-Year Cooperative Agreements RWANDA AFR1603 Grant # F16AP00857 Building capacity for biodiversity conservation in Nyungwe-Kibara-Kahuzi Biega National Parks. In partnership with the Kitabi College of Conservation and Environmental Management. The purpose of this project is to develop a partnership between Rwanda’s Kitabi College and the USFWS to improve regional training opportunities for rangers and other conservationists from Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In particular, the project aims to conserve wildlife and address threats in Rwanda’s Nyungwe National Park, Burundi’s Kibira National Park, and DRC’s Kahuzi-Biega National Park. Specific activities include: (1) providing scholarships for protected area staff to earn diplomas and return to work in their home national parks; (2) developing and incorporating teaching materials into Kitabi College’s curriculum on emerging threats to wildlife and trans-boundary park management. USFWS: $35,000 Leveraged Funds: $11,308 MULTIPLE COUNTRIES CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO AFR1646 Grant # F16AC00508 Reduce poaching of key species within the Chinko, CAR and Garamba, DRC landscapes/ protection areas, with a specific focus on security, intelligence, law enforcement, and park management. -

October 2018 Edition

© Olivier Njounan WWF / Njounan Olivier © A monthly publication of WWF Jengi Programme in Southeast Cameroon October 2018 Edition © Ernest Sumelong WWF / Sumelong © Ernest Our Newsletter moves from a quarterly to a monthly. So much to capture within the Jengi landscape. We are always excited to share with you our stories. Jengi Newsletter, October 2018 Indigenous People WWF, 20 other NGOs and representatives of indigenous peoples have agreed to work in synergy to enhance access rights of Baka and Bagyeli people to protected areas in Southeast Cameroon. For this to be achieved, the NGOs agreed, a memorandum of understanding (MoU) initiated since 2006 between indigenous communities and conservation services of some protected areas, to secure their free access rights, has to be signed. The NGOs met in the town of Abong Mbang in the East Region of Cameroon in a bid to seek ways to accelerate the process for the signing of MoU and to extend the initiative to logging concessions and sports hunting zones. Participants including representatives of Baka and Bagyeli communities, © Ernest Sumelong / WWF WWF and RACOPY (Réseau Recherches Actions Concertées Pygmées) noted significant progress towards obtaining free access rights to natural resources for this vulnerable group. So far, WWF, working with local partners, initiated MoU processes that resulted in the signing of two agreements: one between Bagyelis and the conservation service of Campo Ma’an National Park and the other between Baka and the Ngoyla Wildlife Reserve. “Since the signing of the MoU we have greater access to natural resources in Campo Ma’an National Park,” says Jeanne Biloa, President of Bagyeli Cultural and Development Association (BACUDA). -

CAMEROON's FOREST ESTATE and WILDLIFE June 2011

MINISTRY OF FORESTRY CAMEROON'S FOREST ESTATE AND WILDLIFE June 2011 PROTECTED AREAS AND HUNTING ZONES 9°E 10°E 11°E 12°E 13°E 14°E 15°E 16°E Summary of Number and Area of Land Use Allocation within the National Forest Estate in 2011 Faro Benoué (1) (1) Permanent Forest Estate (PFE) Number Non Permanent Forest Estate (nPFE) Number Area Area N 1 Mbam et Djerem National Park 18 Bouba Ndjida National Park ° 2 Kimbi Wildlife Reserve 19 Faro National Park 8 Production Forests 169 7,613,134 Community Forests 314 1,015,536 N 3 Waza Logone National Park 20 Nki National Park ° 8 Forest Management Units 101 6,586,808 Reserved 27 50,036 4 Kalamaloue National Park 21 Monts Bakossi National Park 5 Mozogo Gokoro National Park 22 Kom National Park Allocated 87 5,545,425 Simple Management Plan 103 276,333 4 6 Lobéké National Park 23 Mengame Gorilla Sanctuary (4) CHAD Unallocated 14 1,041,383 Definitive Management Plan 184 689,167 7 Banyang-Mbo Wildlife Sanctuary 24 Kagwene Gorilla Sanctuary 8 Korup National Park 25 Takamanda National Park Forest Reserves 68 1,026,326 Sales of Standing Volume 49 114,042 9 Rumpi Hills Wildlife Sanctuary 26 Mefou National Park (6) Protected Areas 86 7,397,581 1,129,578 10 Campo Ma'an National Park 27 Ebo National Park 3 Total nPFE 11 Lac Ossa Wildlife Reserve 28 Dja Biosphere Reserve 5 National Parks 24 3,459,798 12 Douala Edea Wildlife Reserve 29 Tchabal Mbabo National Park Wildlife Reserves 5 715,456 Total National Forest Estate (NFE+nPFE) 16,140,293 NIGERIA 13 Santchou Wildlife Reserve 30 Ndongoré National Park 14 Boumba -

Journal Final7.Qxd

CARPOCARPOA quarterly publication of WWF Central African RegionalFOCUSFOCUS Programme Office N° 007 April-June 2006 PreservingPreserving pristinepristine landscapeslandscapes inin thethe CongoCongo BasinBasin Contents Editorial Making bold commitments for Are we winning the race to stop biodiversity loss? 4 conservation Tales from Virunga 6-8 n his opinion note to the The Elephant : Preserving one of nature’s 8th Conference of Parties remaining wonders 9-13 of Convention on IBiological Diversity (CBD) Western Lowland gorillas 14-15 which was held in Curitiba, Brazil from the 20th to the Central African Poverty Alleviation Programme*: 31st of March 2006, James P. From nightmares to real aspirations 16-17 Leape (WWF Director General) said it all: “the Wildlife sanctuary found in Nki National Park 18-19 conservation and sustainable management of forests and Rotterdam to Bayanga*: Switch to conservation the species that live in them engines 20 are critical for the survival of local, rural and indigenous communities in the developing world, many of whom are poor Journey to Virgin Land 21 and have been marginalized by poorly designed development strategies of the past. Bold commitments and ambitious part- Un nouveau Point Focal du programme CARPE nerships are the secret to achieving successful conservation”. en République Démocratique du Congo 23 In the Central African sub region which is host to the world’s second largest tropical forest area, there is need to keep the momentum moving forward ever. Bold commitments are needed to protect animal and plant species that are an essential source of food, materials and shelter for over 20 million people in the sub region. -

12. Monte Alén-Monts De Cristal Landscape

12. Monte Alén-Monts de Cristal Landscape Figure 12.1. Map of Monte Alén-Monts de Cristal Landscape (Sources: CARPE, JRC, SRTM, WCS-Gabon). Location and area he Monte Alén-Monts de Cristal Landscape Th e Landscape in brief Tcovers the south and southeast of Equatorial Guinea and the northwest of Gabon (Figure 12.1). Coordinates: 1°53’35’’N – 0°5’38’’N; 9°37’2’’E – 11°36’3’’E It has an area of approximately 26,747 km2, of Area: 26,747 km2 which about half is located in Equatorial Guinea Elevation: 300-1,250 m and half in Gabon. In Equatorial Guinea, it in- Terrestrial ecoregion: Atlantic Congolese forests ecoregion cludes the Monte Alén and Altos de Nsork na- Aquatic ecoregions: Central West equatorial coastal ecoregion tional parks, as well as the Rio Muni Estuary Southwest equatorial coastal ecoregion Reserve and the Piedra Nzas Natural Monument. Protected areas: In Gabon, it comprises the two sections of Monts Monte Alén National Park, 200,000 ha, 1988/2000, Equatorial Guinea de Cristal National Park. Altos de Nsork National Park, 40,000 ha, 2000, Equatorial Guinea Monts de Cristal National Park, 120,000 ha, 2002, Gabon Physical environment Rio Muni Estuary Reserve, 70,000 ha, 2000, Equatorial Guinea Piedra Nzas Natural Monument, 19,000 ha, 2000, Equatorial Guinea Relief and altitude Th e Landscape occupies a rugged area of pla- teaus and mountain chains mainly situated at an altitude of 300 m to 650 m to the northeast of the coastal sedimentary basin of Gabon (Figure 12.2). In Equatorial Guinea, the highest peak is formed by Monte Mitra, which rises to 1,250 m and is 114 the culminating point of the Niefang chain which runs from the southwest to the northeast. -

Baka Cameroon the Destruction of Congo Basin Tribes in the Name Of

t Parks need peoples The global movement for tribal peoples’ rights The destruction of Congo Basin tribes in the name of conservation How will we survive? Baka Cameroon 1 How will we survive? Introduction The wildlife guards beat us like Les « Pygmées » baka et bayaka,1 comme des douzaines d’autres animals. We want what they’re peuples autochtones de la forêt tropicale du bassin du Congo, doing to end. sont illégalement expulsés de leurs terres ancestrales au nom de la Bayaka woman, Congo, Sept. 4, 2016 conservation de l’environnement. Des parcs nationaux et d’autres zones protégées ont été imposés sur leurs terres sans leur consentement – dans de nombreux cas, suite à une consultation faible voire inexistante. Certaines des plus grandes organisations mondiales de conservation de la nature, tout particulièrement le Fonds mondial pour la nature (WWF) et la Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), sont les principaux responsables du morcellement de leurs territoires. Alors qu’ils chassent à l’intérieur et à l’extérieur de ces zones pour nourrir leurs familles, les Baka et les Bayaka sont accusés de « braconnage ». Avec leurs voisins, ils font face à toutes sortes de harcèlements, sont frappés, torturés et tués. Les milices anti- braconnage qui commettent ces atrocités sont financées et équipées par ces mêmes organisations de protection de la nature. Il est presque certain que les témoignages épouvantables que nous avons recueillis ici ne représentent qu’une infime fraction de ce qui se passe en réalité, la vaste majorité des horreurs perpétrées n’étant pas documentée. Tous ces abus auraient dû faire l’objet d’investigations impartiales, mais sont fréquemment niés et très rarement punis par la loi. -

Boumba Bek National Park Republic of Cameroon Wildlife and Human Impact Survey 2012

Boumba Bek National Park Republic of Cameroon Wildlife and Human Impact Survey 2012 Prepared for: CITES MIKE — Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants CITES MIKE 2012 Boumba Bek National Park survey 1 Personnel: Survey design, data management, mapping: Martha Bechem, Julian Blanc, MIKE Analysis, reporting, interpolation maps: Fiona Maisels, WCS; Martha Bechem, Julian Blanc, MIKE Discriminant analysis of great ape nest data: Samantha StrindberG, WCS Field staff traininG: Martha Bechem, Boafo Yaw, MIKE Field observations: Martha Bechem, MIKE; Jean-Paul Mahop, Independent consultant; Achile MenGamenya, MIKE/MINFOF; Nasere BareGa, MIKE/MINFOF Coordination: Sebastian Luhunu, Martha Bechem, MIKE CITES MIKE 2012 Boumba Bek National Park survey 2 Executive summary 7 Background 8 Elephants and Great Apes in West Central Africa 8 Elephants 8 Great Apes 8 Boumba Bek National Park and MIKE surveys 9 Objective 9 Methods 11 Survey desiGn, 2012 12 Data analysis: elephants 14 Data analysis: Great apes 14 Data analysis: comparinG the results of this survey with previous cycles 15 Results 16 DunG decay survey 16 Dung decay 17 Elephants 17 Elephant abundance 17 Elephant distribution 20 Great apes 21 Great ape abundance 22 Great ape distriBution 23 Human activity 25 General siGns of huntinG and other activities seen on transects 25 Discussion 28 Acknowledgements 29 References 30 Annexs 36 Annex 1. Waypoints for BoumBa Bek, 2012 (Decimal degrees) 36 Annex 2. All elephant dung data from 2012. 39 Annex 3. Mission dates 52 Annex 4. Logistic regression model to separate gorillas from chimps 53 Annex 5. Summary report of 2008. 54 Annex 6. Distance printouts 59 CITES MIKE 2012 Boumba Bek National Park survey 3 CITES MIKE 2012 Boumba Bek National Park survey 4 Figures FiGure 1 Location of Boumba Bek National Park. -

Title SNARE HUNTING AMONG BAKA HUNTER- GATHERERS

SNARE HUNTING AMONG BAKA HUNTER- Title GATHERERS : IMPLICATIONS FOR SUSTAINABLE WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT Author(s) YASUOKA, Hirokazu African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2014), 49: Citation 115-136 Issue Date 2014-08 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/189625 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 49: 115–136, August 2014 115 SNARE HUNTING AMONG BAKA HUNTER-GATHERERS: IMPLICATIONS FOR SUSTAINABLE WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT Hirokazu YASUOKA Faculty of Humanity and Environment, Hosei University ABSTRACT Diversity in hunting methods has been reported among the Mbuti net hunters in Ituri in northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, among the Baka hunters in southeastern Cameroon, who currently practice snare hunting as their principal method, and among other hunter-gatherers in central African forests. Although forest duikers are the main targets of all of these hunters, different species of duikers are captured by different methods. Blue duikers (Philantomba monticola) weighing about 4–5 kg comprise the majority of the Mbuti’s net-hunting harvests, whereas red duikers (in particular, Cephalophus callipygus and C. dorsalis) weighing about 15–20 kg are the major catch in Baka snare hunting. The density of duikers in each area is reflected in the rate of captures: the density of blue duikers is higher in the forests used by Mbuti net hunters, and red duikers are more abundant in the Baka area. Thus, it is likely that the relative abundance of each species is one of the major contributors to the selection of an efficient hunting method. Indeed, non-traditional methods may be selected as a result of adaptation to ecological conditions, the availability of hunting tools, and the changing role of hunting in the livelihoods of hunters. -

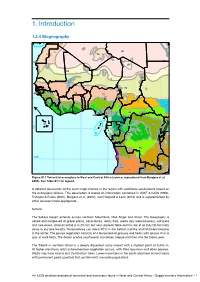

1. Introduction 86

34 85 1. Introduction 86 69 30N 60 1.2.4 Biogeography87 88 93 65 95 98 96 92 97 94 111 99 62 61 35 100 101 115 36 25 70 2 39 83 102 37 38 59 71 1 4 3 4 6 7 5 10 40 44 116 9 103 104 31 12 11 13 16 0 73 41 8 18 14 45 15 17 66 20 47 72 27 43 48 46 42 19 118 112 10S 81 74 50 21 52 82 49 32 26 56 Figure S1.1 Terrestrial ecoregions in West and Central Africa (source: reproduced from Burgess et al. 75 2004). See Table S1.1 for legend. 106 51 119 33 55 64 53 67 63 84 A2 0detailedS description of the eight major biomes in the region with additional subdivisions based on76 29 the ecoregions follows. This description is based on information contained 5in8 WWF6 8& IUCN (1994), 30 Fishpool & Evans (2001), Burgess et al. (2004), and Happold & Lock (2013) and is supplemented57 by 114 other sources where appropriate. 107 54 Terrestrial ecoregions 105 109 113 Sahara Country boundary 22 77 78 The Sahara Desert extends across northern Mauritania, Mali, Niger and Chad. The topography11 7is 28 30S 79 varied and composed of gravel plains, sand dunes, rocky flats, wadis110 (dry watercourses), salt pans 108 23 and rare oases. Annual rainfall is 0–25 mm but very unpredictable and no rain at all may fall for many 0 250 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 80 years in any one locality. -

March April.Qxd

March/April 2008 edition AANTINTI--POACHINGPOACHING Fighting illegal Ivory trade in southeast Cameroon Since WWF started working to protect the rich biodiversity of South East Cameroon in the mid 90s, a lot of progress has been made on the ground. Apart from providing scientif- ic data about key species such as elephants and gorilla that are highly threatened in the area, the WWF Jengi project has boosted its actions by giving support to government to recruit and train game rangers. The presence of these rangers with- in and around the national parks of the South East of Cameroon is yield- ing conservation gains. Forest crimes, especially poaching, are now being increasingly detected, arrested and punished in law courts. Over the past year, dozens of arrests have been made and hundreds of kilogrammes worth of bush meat as well as ivory have been impounded thanks to the work of these rangers supported by forces of law and order. In March 2008 game rangers working in Yokadouma, a town situated some 630km east of Cameroon's capital, Yaoundé, confiscated 13 elephant tusks and made some arrests. The ivory tusks were hidden away in a tight corner of a truck transporting timber from the East of the country to the port city of Douala. Elephant tusks seized from poachers Last year, TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade be making progress out of the sourc- three countries, deep inside the monitoring network, reported that ing zone of illegal ivory trade. Congo Basin rainforest, an extraordi- Central Africa is currently hemorrhag- nary transformation is taking place. ing ivory and cited Cameroon as Lobeke National and its periphery Where poachers, illegal loggers and among three countries in the sub have a high density of African forest traffickers operated at will by simply region most heavily implicated as the elephants estimated at about 5000. -

Undp Project Document

1 UNDP PROJECT DOCUMENT The Government of Cameroon The Government of Congo (Brazzaville) and the Government of Gabon UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM (UNDP) GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY Partners: WWF, WCS, ECOFAC (EU) Project Title: CONSERVATION OF TRANS-BOUNDARY BIODIVERSITY IN THE MINKEBE – ODZALA - DJA INTERZONE IN GABON, CONGO AND CAMEROON Project Number 1583 SUMMARY DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT The Western Congo Basin Moist Forest Ecoregion (WCBMFE) constitutes a large part of the tropical wilderness of Central Africa, the world’s second largest expanse of rainforest. Its globally important biodiversity faces, however, increasingly severe threats from commercial logging and mining, large- scale commercial hunting for wild meat and ivory, often using logging concession access roads. The Governments of Cameroon, Gabon and Congo, through the proposed interventions of this project seek to mitigate these threats while at the same time putting in place the long-term resource management and financing systems needed to achieve conservation objectives. The project will assist the three governments in designing and implementing a coherent land-use plan that designates protected areas, permanent forest and rural development areas, building the capacity to control resource use, to monitor trends in biodiversity and ecosystem functions, through an effective law enforcement system, collaborative management schemes with the private sector and communities, including, in particular, indigenous people, and implementation of a cost-effective monitoring system. The project also seeks to find ways to improve benefits for local communities through revenues generated from alternative livelihoods initiative to ease pressure on natural resource, and setting up a diversified sustainable financing scheme to cover the core management costs in TRIDOM, in particular costs related to law enforcement and protected area management.