Rajesh Ranjan Yadav @ Pappu Yadav Vs Cbi Through Its Director

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating To

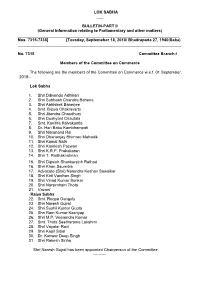

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ________________________________________________________________________ Nos. 7315-7338] [Tuesday, Septemeber 18, 2018/ Bhadrapada 27, 1940(Saka) _________________________________________________________________________ No. 7315 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Commerce The following are the members of the Committee on Commerce w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Shri Dibyendu Adhikari 2. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 3. Shri Abhishek Banerjee 4. Smt. Bijoya Chakravarty 5. Shri Jitendra Chaudhury 6. Shri Dushyant Chautala 7. Smt. Kavitha Kalvakuntla 8. Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati 9. Shri Nityanand Rai 10. Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao Mahadik 11. Shri Kamal Nath 12. Shri Kamlesh Paswan 13. Shri K.R.P. Prabakaran 14. Shri T. Radhakrishnan 15. Shri Dipsinh Shankarsinh Rathod 16. Shri Khan Saumitra 17. Advocate (Shri) Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 18. Shri Kirti Vardhan Singh 19. Shri Vinod Kumar Sonkar 20. Shri Narsimham Thota 21. Vacant Rajya Sabha 22. Smt. Roopa Ganguly 23. Shri Naresh Gujral 24. Shri Sushil Kumar Gupta 25. Shri Ram Kumar Kashyap 26. Shri M.P. Veerendra Kumar 27. Smt. Thota Seetharama Lakshmi 28. Shri Vayalar Ravi 29. Shri Kapil Sibal 30. Dr. Kanwar Deep Singh 31. Shri Rakesh Sinha Shri Naresh Gujral has been appointed Chairperson of the Committee. ---------- No.7316 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Home Affairs The following are the members of the Committee on Home Affairs w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 2. Shri Prem Singh Chandumajra 3. Shri Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 4. Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar 5. Shri Ramen Deka 6. -

32 - Constituency Data - Summary

Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2014 (16th LOK SABHA ) 32 - CONSTITUENCY DATA - SUMMARY State/UT :S04 Code :S04 Constituency :Valmiki Nagar No. :1 MEN WOMEN OTHERS TOTAL I. CANDIDATES 1. NOMINATED 15 0 0 15 2. NOMINATION REJECTED 0 0 0 0 3. WITHDRAWN 1 0 0 1 4. CONTESTED 14 0 0 14 5. FORFEITED DEPOSIT 12 0 0 12 II. ELECTORS 1. GENERAL 786033 670091 50 1456174 2. OVERSEAS 0 0 0 0 3. SERVICE 279 145 424 4. TOTAL 786312 670236 50 1456598 III. VOTERS 1. GENERAL 484433 415396 9 899838 2. OVERSEAS 0 0 0 0 3. PROXY 0 4. POSTAL 331 5. TOTAL 900169 6. Votes Rejected Due to Other Reason 0 III(A). POLLING PERCENTAGE 61.80 IV. VOTES 1. TOTAL VOTES POLLED ON EVM 899838 2. TOTAL DEDUCTED VOTES FROM EVM (TEST VOTES + VOTES NOT RETRIVED+ NOTA) 15515 3. TOTAL VALID VOTES POLLED ON EVM 884323 4. POSTAL VOTES COUNTED 331 5. POSTAL VOTES DEDUCTED (REJECTED POSTAL VOTES + NOTA) 42 6. VALID POSTAL VOTES 289 7. TOTAL VALID VOTES POLLED 884612 8. TEST VOTES POLLED ON EVM 0 9. VOTES POLLED FOR 'NOTA' (INCLUDING POSTAL) 15515 10. TENDERED VOTES 0 V. POLLING STATIONS NUMBER 1391 AVERAGE ELECTORS PER POLLING STATION 1047 DATE(s) OF RE-POLL, IF ANY : null NUMBER OF POLLING STATIONS WHERE RE-POLL WAS ORDERED NIL VI. DATES POLLING COUNTING DECLARATION OF RESULT 12-May-2014 16-May-2014 16-May-2014 VII. RESULT PARTY CANDIDATE VOTES WINNER BJP Satish Chandra Dubey 364013 RUNER-UP INC Purnmasi Ram 246218 MARGIN 117795 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2014 (16th LOK SABHA ) 32 - CONSTITUENCY DATA - SUMMARY State/UT :S04 Code :S04 Constituency :Paschim Champaran No. -

SHRI V V. RAGHAVAN : Sir. We Have a Right to Know. MR DEPUTY

SHRI V V. RAGHAVAN : Sir. we have a right to Speaker was in the Chair and he had suspended even know. question hour and introduced this Bill. He had said that MR DEPUTY SPEAKER I will surely call you also. this Bril would be passed without any discussion. This Please take your seat day would have become a historical day in the name of Indian Parliament in the whole world, but later this / Translation] Bill was referred to the select Committee. Some of few days earlier when I raised this issue, the Parliamentary DR GIRIJA VYAS (Udaipur) : Mr. Deputy Speaker. Affairs Minister said Sir yesterday I wanted to know from Government, through you that what was their intention, of the [English] Government specially when only two days were left7 Seeing the Governments intention quite unfavourable. as expeditiously as possible : Yesterday a demostration was staged by the Women [Translation] Congress but the police ill treated them They arrested 460 women, beat three ladies so bardly that their bones When two days after this issues was raised, he ,jot fractured and got injured in legs. The police snatched said- the purse of so many ladies and threw them out and did [Enghsh] not allow them to march peacefully Yesterday we only wanted to know whether the Government is I can only commit that the Government is serious about the Bill or wanted appreciation from seriously considering this Bill the people and maximum votes in U.P. election But the real intention of the Government is clear now [Translation] that Government is not interested in bringing this All these things are unfavourable for moving of this Bill Bill, there is nothing in favour of it. -

Election Commission of India State Elections - 2005 List of Contesting Candidates

Election Commission of India State Elections - 2005 List of Contesting Candidates Candidate Candidate Party Symbol Votes Status Sl.No Name Abbreviation Polled State Name: Bihar AC No & Name: 1-Dhanaha(GEN) 1 ARTHRAJ YADAV BSP Elephant 2893 Forfeited 2 INDRAJIT YADAV NCP Clock 2985 Forfeited 3 RAGHUNATH PRASAD SAHANI JD(U) Arrow 1716 Forfeited 4 RAJESH SINGH RJD Hurricane 19389 won Lamp 5 ARUN KUMAR TIWARI LJP Bungalow 5073 Forfeited 6 KRISHNA BIHARI PRASAD KUSHWAHA NLP Lock and Key 1848 Forfeited 7 BAWWAN PRASAD YADAV SAP Flaming Torch 3320 Forfeited 8 BAL KHILA THAKUR CPI(ML)(L) Flag with 844 Forfeited Three Stars 9 RAMADHAR YADAV SP Bicycle 13287 Runner-up 10 MANOJ PRASAD IND Envelope 1067 Forfeited 11 MUKESH KUMAR KUSHWAHA IND Cot 10865 Lost AC No & Name: 2-Bagha(SC) 1 DINANATH RAM BSP Elephant 3487 Forfeited 2 NARESH RAM RJD Hurricane 27481 Runner-up Lamp 3 PURNAMASI RAM JD(U) Arrow 59151 won 4 CHHOTE LAL RAM CPI(ML)(L) Flag with 1503 Forfeited Three Stars 5 RAMBHA DEVI LJP Bungalow 3384 Forfeited 6 RAM PRAWESH RAM RLD Aeroplane 1997 Forfeited 7 SUGRIM RAM SHS Axe 1159 Forfeited 8 SURESH RAM SP Bicycle 16175 Forfeited 9 DINESH CHANDRA RAM IND Lock and Key 1355 Forfeited 10 RAMASHANKAR BHAGAT IND Sewing 1554 Forfeited Machine 11 RAMASHISH BAITHA IND Book 1098 Forfeited 12 VISHWANATH RAM IND Letter Box 2393 Forfeited AC No & Name: 3-Ramnagar(GEN) 1 ARJUN VIKRAM SHAH INC Hand 4218 Forfeited 2 CHANDRA MOHAN RAI BJP Lotus 20961 won 3 PRABHAT RANJAN SINGH BSP Elephant 11180 Forfeited Page 1 of Page < 1 > of 171 Candidate Candidate Party Symbol Votes Status Sl.No Name Abbreviation Polled 4 RAM PRASAD YADAV RJD Hurricane 16377 Lost Lamp 5 MD. -

2018 NIC BALLIA 8-10-18 (5128).Xlsx

DPR for Ballia, ULB– Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana BLC-(N) (Urban) 2018 WARD S.N CANDIDATE NAME Caste F/H NAME AGE NO. ADDRESS 1 03 AAASHIM KHATOON 4 MAIHARDDIN KURAISHI 43 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 2 15 AAYASH KHATOON 4 SAKIL AHAMAD 25 RAJENDRA NAGAR ,BALLIA 3 03 ABDUL GAFFAR ANSARI 4 NABBI RASUL 64 KASABTOLA KAJIPURA BALLIA 4 03 ABDUL MAJID 4 ABDUL SAKUR 38 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 5 03 ABDUL RAHEEM 4 NABI RASOOL 50 KASABTOLA KAJIPURA BALLIA 6 14 ABHAY KUMAR 4 JAYRAM 28 RAJPUT NEWARI,BALLIA 7 11 ABHAY KUMAR YADAV 4 VIJAYMAL YADAV 35 MUHAMMADPUR BALLIA 8 13 ABHISHEK KUUMAR SINGH 4 KASHI NATH SINGH 35 TAIGORE NAGAR JEL KE PEECHE 9 11 ADITYA PRASAD KANU 4 VISHWANATH 66 GANDHI NAGAR CHITBARAGAON 10 11 AFASANA KHATOON 1 YUNUSH ANSHARI 26 BAHERI BALLIA 11 03 AFROJ ALI ANSARI 4 MOHAMMAD GAFFAR 37 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 12 16 AFTAB ALAM 4 MD. HABIB 45 RAJPUT NEWARI BALLIA 13 03 AJAM KURAISHI 4 HASIM KURASHI 53 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 14 13 AJAY KUMAR KHARWAR 1 HAR RAM KHARWAR 18 RAMPUR UDDYABHAN NAI BASTI BALLA 15 11 AJAY KUMAR YADAV 4 RAM VILASH YADAV 36 VAJEERAPUR CHANDANPUR BALLIA 16 07 AJAY PASWAN 1 BHARAT PASWAN 31 PURANI BASTI 17 11 AJAY PASWAN 1 SHIV NATH RAM 21 KRISHNA NAGAR, BALLIA 18 11 AJAY YADAV 4 DOMAN YADAV 45 KRISHNA NAGAR KANSHPUR BALLIA 19 13 AJEET KUMAR 4 HARERAM PRASAD 34 RAMPUR UDDYABHAN NAI BASTI BALLA 20 11 AJEET YADAV 4 PARSHURAM YADAV 34 JAPLINGANJ YADAV NAGAR BALLIA 21 03 AKHTAR ALI ANSARI 1 MD JABBAR ASNARI 35 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 22 03 AKHTAR ALI ANSARI 1 NURUL HASAN 59 KAZIPURA ISLAMABAD BALLILA 23 AKHTARI -

(SAKA) 314 and It Has Hampered the Pace of Work

313 SHRAVANA 16, 1919 (SAKA) 314 and it has hampered the pace of work. The construction of the agreement of 1986, signed by then Director, Social work has already been delayed. As a result of delay its cost Welfare Department, Haryana. Due to this, mental and has been escalated. Therefore I would like to urge the physical torture, harassment, exploitation, etc., are going Union Government and demandthat it should immediately on against the bengali refugee-families who remain in the provide the requisite amount to the Uttar Pradesh Mahila Ashram. Their sons may also please be allowed Government sothat the work which has been slowed down inside the Ashram. on the construction of barrage on the Ganges is taken up with full speed and the work is completed on time. Therefore, I would like to urge the Government through you, Sir, that the Central Government may send a message DR. LAXMINARAYAN PANDEY (Mandsaur) : Mr. to the Haryana Government to rehabilitate them Chairman, Sir, due to idleness and short-sightedness of immediately. Thank you. the National Textile Corporation .........(Interruptions) [Translation] MR. CHAIRMAN : You will get a chance. The thing is that, Asim Balaji, your name is already there in the list. The SHRI RAJESH RANJAN ALIAS PAPPU YADAV member of the other party have been accommodated. Shri (Purnea): Mr. Chairman, Sir, thank you very much. Badal Choudhury of your party has already spoken. You will also get a chance. MR. CHAIRMAN : You have already raised this issue last time, therefore I will not allow you more time. DR. LAXMINARAYAN PANDEY : The mills operating under the National Textile Corporation are almost closed [Translation] or on the verge of closure. -

ANSWERED ON:18.12.2015 Regulatory Framework for Crypto-Currencies Gogoi Shri Gaurav;Ranjan (Pappu Yadav) Shri Rajesh;Ranjan Smt

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA FINANCE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:3348 ANSWERED ON:18.12.2015 Regulatory Framework for Crypto-Currencies Gogoi Shri Gaurav;Ranjan (Pappu Yadav) Shri Rajesh;Ranjan Smt. Ranjeet Will the Minister of FINANCE be pleased to state: GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF FINANCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.3348 TO BE ANSWERED ON 18TH DECEMBER, 2015/27TH AGRAHAYANA, SAKA, 1937 REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR CRYPTO-CURRENCIES 3348. SHRIMATI RANJEET RANJAN: SHRI GAURAV GOGOI: SHRI RAJESH RANJAN: QUESTION Will the Minister of FINANCE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has consulted Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to deliberate on a regulatory framework for crypto-currencies like the Bitcoin in India; (b) if so, the details thereof and if not, the reasons therefor; (c) the volume of Bitcoin trade in India as compared to China during the last three years and the current year; (d) if so, the details and the outcome thereof; and (e) whether the Government has taken measures, besides RBI notification dated 24 December, 2013, cautioning users on the risk of virtual currencies and ensure that the unregulated Bitcoins are not accessed for terrorist financing? Answer ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE FOR FINANCE (SHRI JAYANT SINHA) (a) & (b) : Government has consulted Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on the usage, holding and trading of virtual currencies under the extant legal and regulatory framework. (c) to (e) : Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has informed that no such information is available with them. RBI has issued a cautionary advice in December 24, 2013 cautioning the users, holders and traders of virtual currencies about the potential financial, operational, legal, customer protection and security related risks that they are exposing themselves to. -

List of Defective Tokens 3240 Dtd 06022020.Xlsx

List of Defective Tokens Sl. No. Nature/Token No/Year Filing dt. Party Pet. Advocate 1 CWJC/33768/2019 15-10-2019 RANDHIR KUMAR VS. THE STATE OF BIHAR Umesh Prasad Ravi Prakash 2 CWJC/33812/2019 15-10-2019 BABU NAND GIRI VS. THE UNION OF INDIA Dwivedi ASHOK PRASAD KESARI, VS. LALAN Ranjan Kumar 3 CWJC/33933/2019 15-10-2019 PODDAR, Sinha SALIM SAI @ SAMIM ALAM VS. THE STATE 4 CR. MISC./77238/2019 15-10-2019 Rajeev Ranjan OF BIHAR Bipin Bihari 5 CR. MISC./77543/2019 15-10-2019 MD. NOOR ALAM VS. THE STATE OF BIHAR Singh SHASHI GIRI @ SHASHI PRAKASH GOSWAMI Uday Pratap 6 CR. MISC./77695/2019 15-10-2019 @ SHASHI GOSWAMI VS. THE STATE OF Singh BIHAR JAY NARAYAN RAJAK VS. THE STATE OF Ranjeet 7 CWJC/34050/2019 16-10-2019 BIHAR Kumar MUKESH AGRAWAL ALIAS MUKESH 8 CWJC/34144/2019 16-10-2019 Gyanand Roy SAH VS. THE STATE OF BIHAR Umesh MANOJ KUMAR YADAV @ MANOJ 9 CR. MISC./77960/2019 16-10-2019 Chandra RAY VS. THE STATE OF BIHAR Verma RAJESH RANJAN @ PAPPU YADAV VS. THE Rajesh Ranjan 10 CWJC/34296/2019 17-10-2019 STATE OF BIHAR (IN PERSON) SONI SINGH @ SONI VS. THE STATE OF Ajay Kumar 11 CR. WJC/78642/2019 17-10-2019 BIHAR THROUGH THE CHIEF SECRETARY Singh GOVT. OF BIHAR, PATNA TARUNNUM KHATOON @ TARANNUM Ajay Kumar 12 CR. MISC./78729/2019 17-10-2019 KHATUN VS. THE STATE OF BIHAR Tiwary MUNNI DEVI, VS. VIJAY CHANDRA 13 C.Misc./34454/2019 18-10-2019 Sandeep Patil SAHUKAR, M/S. -

Cmcollege,Darbhanga

C.M.COLLEGE,DARBHANGA ELECTION OF STUDENTS UNION 2019-20 STUDENTS ELECTORAL ROLL SUBJECT- B.COM SESSION- 2018-21 PART- 2nd (SECOND) CLASS S.NO. ROLL NAME FATHER`S NAME SIGNATURE / REMARKS NO. 1 01 JUHI SINHA SHASHI BHUSHAN PRASAD SINHA 2 02 RAUSHAN KUMAR JHA AMARNATH JHA 3 03 AJAY KUMAR YADAV DHANIK LAL YADAV 4 04 MUKUND KUMAR ASHOK KUMAR JHA 5 05 DEEPAK KUMAR MANDAL UMESH MANDAL 6 06 BHAGWANJEE KUMAR DILEEP JHA 7 07 KRISHNA KUMAR LADDU KAMTI 8 08 RAKESH KUMAR JHA ASHOK KUMAR 9 09 AASHIA AQUEEL AQUEEL ANSARI 10 10 KAMDEV MANDAL KARI MANDAL 11 11 AMIT KUMAR MANDAL MITHELESH MANDAL 12 12 MD IRSHAD MD NAVI HASAN 13 13 MEGHA KUMARI RADHE SHYAM MAHTHA 14 14 SAIMA AFAQUE MOHAMMAD AFAQUE 15 15 SAIQA PARWEEN ABADUR RAHAMAN 16 16 SURAJ SHARMA KAILASH KUMAR SHARMA 17 17 NITISH KUMAR SHARMA SHIV SHANKAR SHARMA 18 18 MANTOSH KUMAR SHARMA SITARAM SHARMA 19 19 GAURISHANKAR KAMATI BACHCHELAL KAMATI 20 20 SANU KUMAR SURESH SAH 21 21 VIMAL KUMAR KHAN RAJ KUMAR KHAN 22 22 MUKESH KUMAR RAMBABU YADAV 23 23 JAY PRAKASH BHOLA PRASAD SAH 24 24 LAXMI KUMARI DILEEP SAH 25 25 POONAM KUMARI WAKIL YADAV 26 26 SANJIV KUMAR THAKUR RAVINDRA THAKUR 27 28 SOHAN PASWAN LALIT PASWAN 28 29 KIRTI KUMARI DHRUV DEV SINGH 29 30 GUDDU KUMAR DAHU SAHNI 30 31 NOURMY KUMARI NAGENDRA KUMAR 31 32 RICHA PRIYAM ARVIND CHANDRA THAKUR Page 1 of 221 32 33 ANJANA KUMARI RAM BABU PRASAD 33 34 CHINMAY SHANKAR PRASHD UMA SHANKAR PRASAD 34 35 GULISTA AAFREEN SAGHEER ANSARI 35 36 ABHISHEK BHANDARI DAYA SHANKAR BHANDARI 36 37 KOMAL KUMARI UMESH PRASAD 37 38 MD GULZAR AHMAD MD WALI AHMAD 38 39 -

Sr. No. Candidate Name User Name Mobile NO. District Education

Final Education OnCeT Sr. No. Candidate Name User Name Mobile NO. District Result Qualification Certified Status 1 MANISH KUMAR [email protected] 7739215731 Madhepura HSC Pass Yes 2 DEEPAK KUMAR [email protected] 8651332222 Rohtas BE/BTech Pass Yes 3 MD MOHSIN [email protected] 9064360641 Kishanganj HSC Pass Yes 4 AAISHA ZAKI [email protected] 8434510982 Madhepura HSC Pass Yes 5 Aalok Chandra [email protected] 8709997423 Darbhanga BSc/BCS Pass Yes 6 ARSHI ZAKI [email protected] 9386962414 Madhepura HSC Pass Yes 7 Aarushi Kriti [email protected] 6202569553 Kishanganj BSc/BCS Pass Yes 8 ABHA KUMARI [email protected] 6203643535 Madhepura HSC Pass Yes 9 ABHAYANAND . [email protected] 9122599329 Rohtas HSC Pass Yes 10 ABHIJEET SHARMA [email protected] 9973155834 Siwan HSC Pass Yes 11 ABHILASHA KUMARI [email protected] 9304948496 Begusarai BSc/BCS Pass Yes 12 ABHINANDAN KUMAR [email protected] 9534779817 Madhepura BA Pass Yes 13 Abhishek Kumar [email protected] 8863981599 Saharsa BSc/BCS Pass Yes 14 BANSHIDHAR KUMAR [email protected] 7462900787 Begusarai BSc/BCS Pass Yes 15 ABHISHEK KUMAR [email protected] 9304329543 Khagaria HSC Pass Yes 16 Adarsh Tiwari [email protected] 7368078281 Saran HSC Pass Yes 17 ADITYA GAURAV [email protected] 7004734840 Khagaria BSc/BCS Pass Yes 18 AHMAD RAZA [email protected] 8051406582 Begusarai BSc/BCS -

207 Business of the House MARCH 6, 1997 Business of the House

Business of the House 208 207 Business of the House MARCH 6, 1997 SHRI CHAMAN LAL GUPTA (UDHAMPUR): Sir, the To discuss the demand for including the coal based following items may be included in the next week’s agenda: Thermal Power Project, Nabinagar in the ninth Five Year Plan for solving the power problem in Bihar. 1. An Ex-gratia grant of Rs. one lakh to each of the families affected by terrorism in district Doda and immediate employment to at least, one member of these families: [Translation] 2. To solve the drinking water problem in Katra and SHRI RAJESH RANJAN Alias PAPPU YADAV Vaishno Devi Shrine which is visited by 50 lakh pilgrims (PURNIA): Mr, Speaker, Sir Thank you very much for every year. having paid attention towards Bihar and for giving me a SHRI SHIVRAJ SINGH (VIDISHA): Mr. Speaker, Sir, chance to speak. One week ago I had given certain the following items may be included in the next weeks information to the House in respect of jute and sugracane agenda: in Bihar wherein I had highlighted two important things. 1. To discuss the need to check the increasing naxalite The constituency which I represent is the largest jute activities in Baster, Balaghat and Rajnandgaon districts of growing area in north Bihar bordering Nepal and Bengal Madhya Pradesh. the area Irom western Champaran to Vitarwa in North Bihar adjoining the border of Nepal is the largest sugarcane 2. Discussion on the increasing power crisis in the growing area. I have to make two main points in respect ocuntry, particularly in Madhya Pradesh. -

Nationallistofmpsnominatedasc

Members of Parliament (16th Lok Sabha) Nominated as Chairman/ Co-chairman to the District Vigilance & Monitoring Committees ANDHRA PRADESH District Member of Parliament Chairman/Co-Chairman Shri Kristappa Nimmala Chairman Anantapur Shri J.C. Divakar Reddy Co-Chairman Dr. Naramalli Sivaprasad Chairman Chittoor Shri Midhun Reddy Co-Chairman Dr. Vara Prasadarao Velagapalli Co-Chairman Shri Murali Mohan Maganti Chairman Shri Narasimham Thota Co-Chairman East Godavari Dr. Ravindra Babu Pandula Co-Chairman Smt. Geetha Kothapalli Co-Chairperson Shri Rayapati Sambasiva Rao Chairman Guntur Shri Jayadev Galla Co-Chairman Shri Sriram Malyadri Co-Chairman Shri Y. S. Avinash Reddy Chairman Kadapa Shri Midhunn Reddy Co-Chairman Shri Konakalla Narayana Rao Chairman Krishna Shri Srinivas Kesineni Co-Chairman Shri Venkateswara Rao Magantti Co-Chairman Shri S.P.Y. Reddey Chairman Kurnool Smt. Renuka Butta Co-Chairperson Shri Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy Chairman Nellore Dr. Vara Prasadarao Velagapalli Co-Chairman Shri Yerram Venkata Subbareddy Chairman Prakasam Shri Sriram Malyadri Co-Chairman Shri Mekpati Rajamohan Reddy Co-Chairman Shri Ashok Gajapati Raju Pusapati Chairman Srikakulam Shri Kinjarapu Ram Mohan Naidu Co-Chairman Smt. Geetha Kothapalli Co-Chairperson Smt. Geetha Kothapalli Chairperson Vishakhapatnam Shri Muthamsetti Srinivasa Rao (Avnthi) Co-Chairman Shri. Hari Babu Kambhampati Co-Chairman Shri Ashok Gajapati Raju Pusapati Chairman Vizianagaram Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati, Co-Chairman Smt. Geetha Kothapalli Co-Chairperson Shri Venkateswara Rao