1 Dear Birdos4eric, What Better Place to Visit at the Height of Spring Than

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

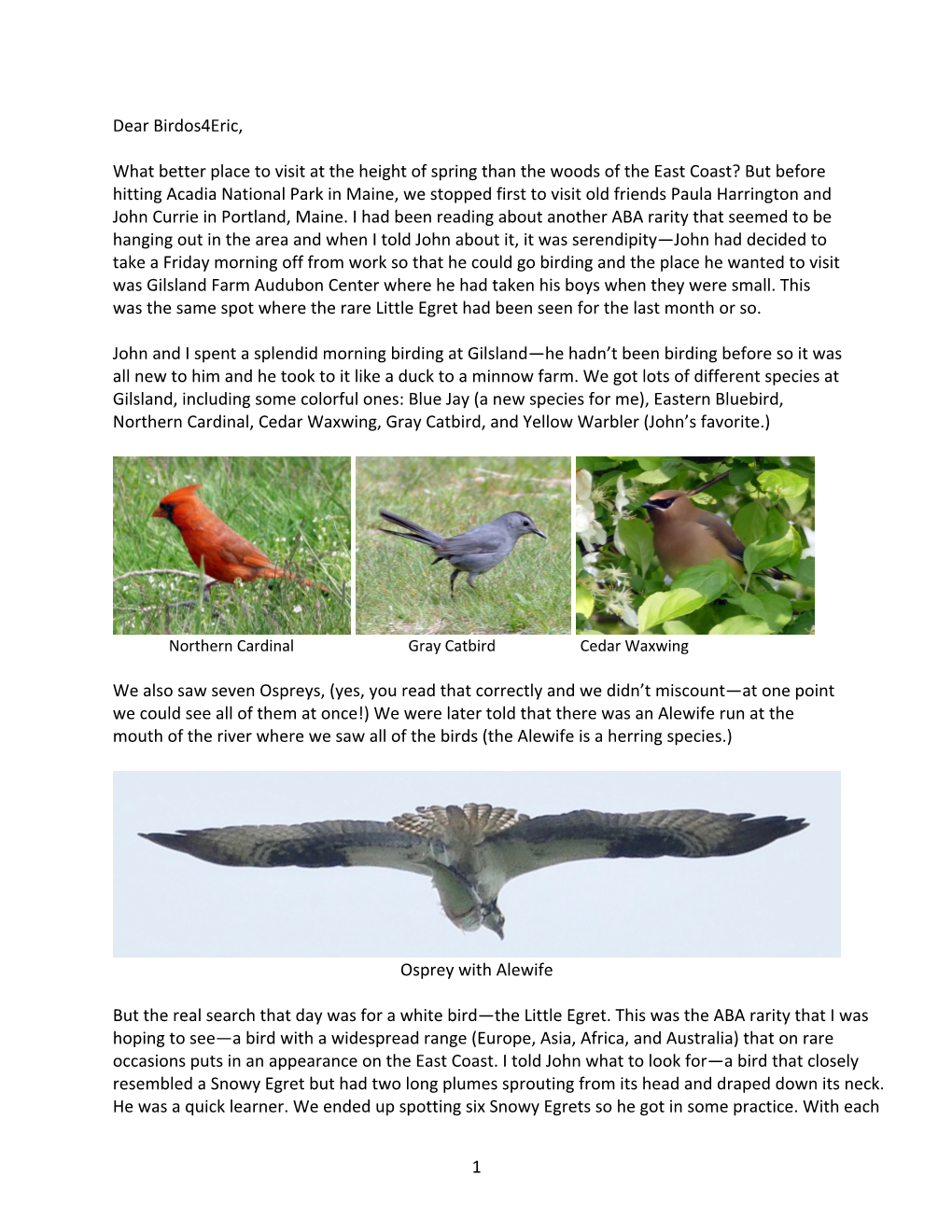

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grey Heron

Bird Life The Grey Heron t is quite likely that if someone points out a grey heron to you, I you will remember it the next time you see it. The grey heron is a tall bird, usually about 80cm to 1m in height and is common to inland waterways and coasts. Though the grey heron has a loud “fraank” call, it can most often be seen standing silently in shallow water with its long neck outstretched, watching the water for any sign of movement. The grey heron is usually found on its own, although some may feed close together. Their main food is fish, but they will take small mammals, insects, frogs and even young birds. Because of their habit of occasionally taking young birds, herons are not always popular and are often driven away from a feeding area by intensive mobbing. Mobbing is when smaller birds fly aggressively at their predator, in this case the heron, in order to defend their nests or their lives. Like all herons, grey herons breed in a colony called a heronry. They mostly nest in tall trees and bushes, but sometimes they nest on the ground or on ledge of rock by the sea. Nesting starts in February,when the birds perform elaborate displays and make noisy callings. They lay between 3-5 greenish-blue eggs, often stained white by the birds’ droppings. Once hatched, the young © Illustration: Audrey Murphy make continuous squawking noises as they wait to be fed by their parents. And though it doesn’t sound too pleasant, the parent Latin Name: Ardea cinerea swallows the food and brings it up again at the nest, where the Irish Name: Corr réisc young put their bills right inside their parents mouth in order to Colour: Grey back, white head and retrieve it! neck, with a black crest on head. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

The First Breeding Record of Glossy Ibises Plegadis Falcinellus for Cyprus MICHAEL MILTIADOU

The first breeding record of Glossy Ibises Plegadis falcinellus for Cyprus MICHAEL MILTIADOU The Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus is a common passage migrant in Cyprus particularly during spring, (Feb) Mar–May, with smaller numbers staging at the wetlands in autumn, Aug–Sep (Oct). Large flocks migrate off the coast of Cyprus during autumn (Flint & Stewart 1992). Migrating flocks of the species are usually observed flying around the coast or over-flying the island but during wet springs, when coastal wetlands are waterlogged, these flocks might stage for a week or more. However, ten pairs of Glossy Ibises were observed nesting at the Ayios Lucas lake heronry, Famagusta, April–July 2010, the first breeding record for Cyprus (Miltiadou 2010). Although only a small percentage of the global population of Glossy Ibises breeds in Europe that population has exhibited a moderate decline and is evaluated by BirdLife International as a ‘Species of European Concern, Declining’ (Burfield & van Bommel 2004). It breeds in three eastern Mediterranean countries around Cyprus: Turkey (500–1000 pairs), Greece (150–200 pairs) and Israel (c300 pairs) (Cramp & Simmons 1978, Burfield & van Bommel 2004). Ayios Lucas lake (Plate 1), aka Famagusta Freshwater lake, is a lake that was created by damming part of a seasonal lake basin situated on the northwest side of Famagusta city at Limni, and is bordered on the north by the Nicosia–Famagusta motorway. It is part of a seasonal flood plain that opens into a brackish delta created by the joining of the Pediaeos and Yialias intermittent rivers. The delta spreads between Famagusta and Salamis and is located at the eastern end of the Mesaoria plain that runs across the middle of Cyprus. -

THE LITTLE EGRET in SOUTH AUSTRALIA (By H

September, 1958 THE S.A. ORNITHOLOGIST 77 THE LITTLE EGRET IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA (By H. T. CONDON) Since World War II there has been an who have regularly reported the Brown Bit- increase in the amount of information in bird tern [Botaurus] from districts where it un- literature dealing with sight identifications doubtedly occurs, yet I have found that and habits and it is now a fairly simple these people did not know the difference he- matter to recognise species once thought im- tween the bittern and the young of the possible. Unfortun~tely, much of ~e newl~. Nankeen Night Heron (Nycticorax)! acquired knowledge IS swallowed by mexpen- Mistakes in sight identifications are some. enced or uncritical observers with no good times understandable, but those due to ignor- effects. In this connection I am thinking ance and carelessness can be avoided. An more especially of the increasingly bold and observer should constantly guard against aggressive claims for rare ?r u~usu.al water wishful thinking, a common fault, which is birds which have appeared In print In recent responsible for the majority of problematical years. ". ." claims. Many of these claims are inconclusive, to Future sight records of the Little Egret are say the least, and I believe that the stage desi bl lv i f h f 11 . has now been reached where it is impossible esira e on y In one Or more 0 teo OWIng li circumstances. to accept any new record for South Austra .a 1. Observations in connection with nest. without a specimen. ing activities which can be investigated. -

Nesting Period and Breeding Success of the Little Egret Egretta Garzetta in Pattani Province, Thailand

FORKTAIL 29 (2013): 120–123 Nesting period and breeding success of the Little Egret Egretta garzetta in Pattani province, Thailand SOMSAK BUATIP, WANCHAMAI KARNTANUT & CORNELIS SWENNEN Nesting of Little Egret Egretta garzetta was studied between October 2008 and September 2009 in a colony near Pattani, southern Thailand, where the species is a recent colonist. Nesting was bimodal over a 12-month observation period. The first nesting period started in December in the middle of the rainy season (November–December). The second period started in March during the dry season (February–April). In the second period, nesting began in an area not occupied during the first period but gradually expanded into areas used in the first period. Egg and chick losses were high; the mean number of chicks that reached two weeks of age was 1.0 ± 1.2 (n = 467 nests), based on nests that had contained at least one egg. Considerable heterogeneity of clutch size and nest success was apparent between different locations within the colony. The main predator appeared to be the Malayan Water Monitor Varanus salvator. INTRODUCTION breeding success; understand nesting synchrony; and finally document if breeding success parameters varied spatially within the The breeding range of the Little Egret Egretta garzetta extends from focal colony. western Europe (northern limit about 53°N) and North Africa across Asia south of the Himalayas to east Asia including Korea and Japan (northern limits about 40°N), with some isolated areas MATERIALS AND METHODS in southern Africa, the Philippines and north and east Australia (Hancock et al. 1978, Wong et al. -

Egret and Glossy Ibis Rookeries

Emu - Austral Ornithology ISSN: 0158-4197 (Print) 1448-5540 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/temu20 Egret and Glossy Ibis Rookeries F. C. Morse To cite this article: F. C. Morse (1922) Egret and Glossy Ibis Rookeries, Emu - Austral Ornithology, 22:1, 36-38, DOI: 10.1071/MU922036 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1071/MU922036 Published online: 22 Dec 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1 View related articles Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=temu20 The Emu. 36 !ITO RSE, Birds of the Moree District. [ 1st July Egret and Glossy Ibis Rookeries By F. C. MORSE, R.A.O.U., Coocalla, Garah, ~.S.W. For many years I have been firmly convinced that the Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) bred somewhere along the 70 miles of \Vatcrcourse in this district, and, in company >vith Mr. H. A. Mawhiney, I have spent many days 1n search of their nests. TilE Ei\HJ, Vol. XXll. PLATE XIV. Vol. XXII.) 1922 :l\-10RSE, Fll'rds of the Moree District. 37 On almost every trip we made to various points in this vast expanse of swamps the birds were seen, but no sign of a nest was found. 1'o help us in the quest, we questioned every pen;on ·we met living anyv.·here near the wet area. Most of them did not even know the bird. \Ve were fortunate in at last meeting Mr. S. -

Waterbirds & Raptors of Coastal

Waterbirds & Raptors of Coastal SEQ An Identification Guide Trevor Ford Map of Coastal SEQ Waterbirds & Raptors of Coastal SEQ R Inglis An Identification Guide Trevor Ford 1 First published in 2011. This booklet may not be produced or transmitted in whole or part, in any form, without prior permission from the author. Printed by Platypus Graphics, Stafford, Brisbane, Qld. The photographs of the Australasian Grebe on the front cover and the roosting Royal Spoonbills on the back cover were taken by Robert Inglis. The photograph on page one is of an Eastern Osprey. The photograph below is of a mixed flock of ducks and geese. The Coastal SEQ map (inside front cover) identifies the five funding councils. W Jolly 2 Contents Page Introduction 4 Waterbirds 4 Raptors 5 Conservation 5 Birding locations 6 Sunshine Coast 6 Moreton Bay 7 Brisbane 7 Redlands 7 Gold Coast 8 Species identification 8 Identification guide 9 Waterbirds 10 Raptors 51 Index of species 66 Acknowledgements 68 3 Introduction This booklet provides an introduction to the waterbirds and raptors of coastal South East Queensland (SEQ), detailing conservation challenges and providing an outline of some easily-accessible sites where many of these species can be seen. The main section of the booklet is an identification guide, describing the waterbirds and raptors that are most likely to be encountered in the region. Hopefully, by raising the general awareness of these special birds and the problems that they face, actions will be taken to help them survive. Waterbirds The waterbirds covered in this booklet come from a diverse range of bird groups that includes grebes, cormorants, herons, spoonbills, ibises, ducks, geese, swans, cranes, gallinules, rails and crakes. -

Cattle Egret Bubulcus Ibis Habitat Use and Association with Cattle

174 SHORT NOTES Forktail 21 (2005) REFERENCES Mauro, I. (2001) Cinnabar Hawk Owl Ninox ios at Lore Lindu National Park, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, in December 1998. Lee, R. J. and Riley, J. (2001) Morphology, plumage, and habitat of Forktail 17: 118–119. the newly described Cinnabar Hawk-Owl from North Sulawesi, Rasmussen, P. C. (1999) A new species of hawk-owl Ninox from Indonesia. Wilson Bull. 113(1): 17–22. North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Wilson Bull. 111(4): 457–464. Ben King, Ornithology Dept., American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th St., New York, NY10024, U.S.A. Email: [email protected] Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis habitat use and association with cattle K. SEEDIKKOYA, P. A. AZEEZ and E. A. A. SHUKKUR Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis has a worldwide distribution. made five counts per day from 06h00 to 18h00. Egrets In India it is common in a variety of habitats, especially were defined as associated with cattle if they were wetlands, throughout the peninsula. Freshwater found <1 m from an animal and were alert to its marshes and paddy fields were identified as the most movements. We carried out focal observations on important foraging habitats by Meyerricks (1962) and randomly selected foraging egrets, during which we Seedikkoya (2004), although there are pronounced recorded number of strikes, successful captures seasonal variations in the usage of these habitats. Cattle (identified by the characteristic head-jerk swallowing Egrets are often found associated with cattle and behaviour: Heatwole 1965, Dinsmore 1973, Grubb occasionally with pigs, goats, and horses, and also with 1976, Scott 1984) and number of steps in a two- moving vehicles such as tractors. -

Comparative Breeding Ecology of the Little Egret (Egretta G. Garzetta) in the Axios Delta (Greece) and the Camargue (France)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by I-Revues COMPARATIVE BREEDING ECOLOGY OF THE LITTLE EGRET (EGRETTA G. GARZETTA) IN THE AXIOS DELTA (GREECE) AND THE CAMARGUE (FRANCE) Savas KAZANTZIDIS 1, Heinz HAFNER2 & Vassilis GOURNER 1 INTRODUCTION In the Mediterranean region the Little Egret (Egretta garzetta) has a patchy breeding distribution (Cramp & Simmons, 1984 ; Hafner et al., 1987). Since the seventies the species has generated considerable interest for the study of the breeding and feeding ecology, in the Camargue in southern France (e.g. Vo isin, 1978, 1979 ; Hafner, 1977, 1978 ; Hafner & Britton, 1983 ; Hafner et al., 1982, 1986, 1993, 1994 ; Kersten et .al. , 1992), in ltaly (e.g. Fasola, 1986 ; Fasola & Ghidini, 1983 ; Fasola & Barbieri, 1978 ; Fasola & Alieri, 1992), in Spain (Fernandez-Cruz, 1995 ; Fernandez-Cruz et al., 1992), in Greece (Tsachilidis, 1990 ; Kazantzidis & Goutner, 1996) and in Croatia (Mikuska, 1992). Egrets carrying wing marks and originating from the Camargue are frequently observed in Spain but there is also evidence of dispersal in an easterly direction (Pineau, 1992), and sorne of these birds have been observed in Greece (Hafner, unpubl. data). According to migration movements analysed by Vo isin (1985, 1991) Little Egrets from the different breeding areas in southern Europe are most Iikely to mix during migration and wintering and are part of a metapopulation system. We compare data on the breeding biology of Little Egrets in two Mediterra nean wetlands of international importance. The physical and biotic characteristics of foraging habitat differ considerably between the two wetlands and we investigate whether the breeding performance and chick condition reflect this inter-regional variation. -

Featured Photo HYBRIDIZATION of a YELLOW-CROWNED and BLACK-CROWNED NIGHT-HERON in SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA MARY F

FEATURED PHOTO HYBRIDIZATION OF A YELLOW-CROWNED AND BLACK-CROWNED NIGHT-HERON IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA MARY F. PLATTER-RIEGER, 2104 Crenshaw Street, San Diego California 92105- 5130, [email protected] TIFFANY M. SHEPHERD, Naval Facilities Engineering Command Southwest, 1220 Pacific Highway, San Diego, California 92132; [email protected] MARIE MOLLOY, Wildlife Assist Volunteers, 4203 Genesee Avenue #103, San Diego, California 92117, [email protected] We report the second successful hybridization in the wild between a Yellow-crowned Night-Heron (Nyctanassa violacea) and a Black-crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), and the first with observations of young on the nest. Hybridization among herons is uncommon but has been reported previously for the Black-crowned Night-Heron (McCarthy 2006, Monson and Phillips 1981). These reports include a natural cross with either a Little Blue Heron (Egretta caerulea) or a Tricolored Heron (E. tricolor) where the exact identification was uncertain. In Java, Sulawesi, and the Philippines natural hybridization between the Black-crowned Night-Heron and Rufous Night-Heron (Nycticorax caledonicus) has been noted repeatedly (McCarthy 2006). In captivity a Black-crowned Night-Heron crossed with a Little Egret (Egretta garzetta), but these species’ breeding ranges overlap so a natu- ral hybrid is also possible (McCarthy 2006). A captive Black-crowned Night-Heron crossed with a Yellow-crowned Night-Heron in 1975 at the Dallas Zoo, Texas; these species’ breeding ranges overlap as well (McCarthy 2006). In captivity many cases of hybridization are due to proximity and lack of choice in mates and never occur under natural circumstances in the wild. Until recently, the only reported natural hybrid between the Yellow-crowned Night- Heron and the Black-crowned Night-Heron was collected in 1951 north of Prescott, Arizona (Monson and Phillips 1981). -

Little Egret Egretta Garzetta

Little egret Egretta garzetta Description Thirty years ago, you would have been very lucky to have spotted a little egret in the UK. Once a very rare visitor from the continent, the little egret is now a common sight around the coastline of southern England and Wales. It first appeared in the UK in the late 1980s, and first bred in Dorset in 1996 and Wales in 2002. This small white heron has elegant white plumage and a long neck, a black dagger-like beak, long dark green-black legs, and yellow feet. At rest, the little egret often hunches and can look small and rather miserable. When flying, their head and long neck retract, and the legs and feet extend beyond the tail. In breeding season, the little egret develops a long drooping head crest and long trailing wing plumes. Their magnificent feathers were once more valuable than gold and were smuggled into Europe in the 19th Century to be used in the hat trade. What they eat The little egret feeds on small fish and crustaceans, but will also take amphibians and large insects. They can often be seen paddling enthusiastically in the mud to disturb their prey. Where and when to see them z They are mainly found on estuaries and coastal waterways, and occasionally on inland wetlands. z They can be seen all year round, although numbers increase in autumn and winter as birds arrive from the continent. z Don’t forget to look up! Little egrets usually breed and roost colonially in bushes and trees near water. -

Effects of Research Disturbance on Nest Survival in a Mixed Colony of Waterbirds

Effects of research disturbance on nest survival in a mixed colony of waterbirds Jocelyn Champagnon, Hugo Carré and Lisa Gili Tour du Valat, Research Institute for Conservation of Mediterranean Wetlands, Arles, France ABSTRACT Background. Long-term research is crucial for the conservation and development of knowledge in ecology; however, it is essential to quantify and minimize any negative effects associated with research to gather reliable and representative long-term monitoring data. In colonial bird species, chicks are often marked with coded bands in order to assess demographic parameters of the population. Banding chicks in multi- species colonies is challenging because it involves disturbances to species that are at different stages of progress in their reproduction. Methods. We took advantage of a long term banding program launched on Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) breeding in a major mixed colony of herons in Camargue, southern France, to assess the effect of banding operation disturbance on the reproductive success of the three most numerous waterbirds species in the colony. Over two breeding seasons (2015 and 2016), 336 nests of Glossy Ibis, Little Egrets (Egretta garzetta) and Cattle Egrets (Bubulcus ibis) were monitored from a floating blind in two zones of the colony: one zone disturbed twice a year by the banding activities and another not disturbed (control zone). We applied a logistic-exposure analysis method to estimate the daily survival rate (DSR) of nests and chicks aged up to three weeks. Results. Daily survival rate of Glossy Ibis was reduced in the disturbed zone while DSR increased for Little and Cattle Egrets in the disturbed zone.