1847 Cellarius Mazurka Waltz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

Bizourka and Freestyle Flemish Mazurka

118 Bizourka and Freestyle Flemish Mazurka (Flanders, Belgium, Northern France) These are easy-going Flemish mazurka (also spelled mazourka) variations which Richard learned while attending a Carnaval ball near Dunkerque, northern France, in 2009. Participants at the ball were mostly locals, but also included dancers from Belgium and various parts of France. Older Flemish mazurka is usually comprised of combina- tions of the Mazurka Step and Waltz, in various simple patterns (see Freestyle Flemish Mazurka below). Like most folk mazurkas, their style descended from the Polka Mazurka once done in European ballrooms, over 150 years ago. This folk process is sometimes compared to a bridge. French or English dance masters picked up an ethnic dance step, in this case a mazurka step from the Polish Mazur, and standardized it for ballroom use. It was then spread throughout the world by itinerant dance teachers, visiting social dancers, and thousands of easily available dance manuals. From this propagation, the most popular steps (the Polka Mazurka was indeed one of the favorites) then “sank” through many simplified forms in villages throughout Europe, the Americas, Australia and elsewhere. In other words, towns in rural France or England didn’t get their mazurka step directly from Poland, or their polka directly from Bohemia, but rather through the “bridge” of dance teachers, traveling social dancers and books, that spread the ballroom versions of the original ethnic steps throughout the world. Once the steps left the formal setting of the ballroom, they quickly simplified. Then folk dances evolve. Typically steps and styles are borrowed from other dance forms that the dancers also happen to know, adding a twist to a traditional form. -

The Haybaler's

The Haybaler’s Jig An 11 x 32 bar jig for 4 couples in a square. Composed 4 June 2013 by Stanford Ceili. Mixer variant of Haymaker’s Jig. (24) Ring Into The Center, Pass Through, Set. (4) Ring Into The Center. (4) Pass through (pass opposite by Right shoulders).1 (4) Set twice. (12) Repeat.2 (32) Corners Dance. (4) 1st corners turn by Right elbow. (4) 2nd corners repeat. (4) 1st corners turn by Left elbow. (4) 2nd corners repeat. (8) 1st corners swing (“long swing”). (8) 2nd corners repeat. (16) Reel The Set. Note: dancers always turn people of the opposite gender in this figure. (4) #1 couple turn once and a half by Right elbow. (2) Turn top side-couple dancers by Left elbow once around. (2) Turn partner in center by Right elbow once and a half. (2) Repeat with next side-couple dancer. (2) Repeat with partner. (2) Repeat with #2 couple dancer. (2) Repeat with partner. (2) #1 Couple To The Top. 1Based on the “Drawers” figure from the Russian Mazurka Quadrille. All pass their opposites by Right shoulder to opposite’s position. Ladies dance quickly at first, to pass their corners; then men dance quickly, to pass their contra-corners. 2Pass again by Right shoulders, with ladies passing the first man and then allowing the second man to pass her. This time, ladies pass their contra-corners, and are passed by their corners. (14) Cast Off, Arch, Turn. (12) Cast off and arch. #1 couple casts off at the top, each on own side. -

Chopin and Poland Cory Mckay Departments of Music and Computer Science University of Guelph Guelph, Ontario, Canada, N1G 2W 1

Chopin and Poland Cory McKay Departments of Music and Computer Science University of Guelph Guelph, Ontario, Canada, N1G 2W 1 The nineteenth century was a time when he had a Polish mother and was raised in people were looking for something new and Poland, his father was French. Finally, there exciting in the arts. The Romantics valued is no doubt that Chopin was trained exten- the exotic and many artists, writers and sively in the conventional musical styles of composers created works that conjured im- western Europe while growing up in Poland. ages of distant places, in terms of both time It is thus understandable that at first glance and location. Nationalist movements were some would see the Polish influence on rising up all over Europe, leading to an em- Chopin's music as trivial. Indeed, there cer- phasis on distinctive cultural styles in music tainly are compositions of his which show rather than an international homogeneity. very little Polish influence. However, upon Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin used this op- further investigation, it becomes clear that portunity to go beyond the conventions of the music that he heard in Poland while his time and introduce music that had the growing up did indeed have a persistent and unique character of his native Poland to the pervasive influence on a large proportion of ears of western Europe. Chopin wrote music his music. with a distinctly Polish flare that was influ- The Polish influence is most obviously ential in the Polish nationalist movement. seen in Chopin's polonaises and mazurkas, Before proceeding to discuss the politi- both of which are traditional Polish dance cal aspect of Chopin's work, it is first neces- forms. -

A/L CHOPIN's MAZURKA

17, ~A/l CHOPIN'S MAZURKA: A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF J. S. BACH--F. BUSONI, D. SCARLATTI, W. A. MOZART, L. V. BEETHOVEN, F. SCHUBERT, F. CHOPIN, M. RAVEL AND K. SZYMANOWSKI DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial. Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Jan Bogdan Drath Denton, Texas August, 1969 (Z Jan Bogdan Drath 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . I PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS First Recital . , , . ., * * 4 Second Recital. 8 Solo and Chamber Music Recital. 11 Lecture-Recital: "Chopin's Mazurka" . 14 List of Illustrations Text of the Lecture Bibliography TAPED RECORDINGS OF PERFORMANCES . Enclosed iii INTRODUCTION This dissertation consists of four programs: one lec- ture-recital, two recitals for piano solo, and one (the Schubert program) in combination with other instruments. The repertoire of the complete series of concerts was chosen with the intention of demonstrating the ability of the per- former to project music of various types and composed in different periods. The first program featured two complete sets of Concert Etudes, showing how a nineteenth-century composer (Chopin) and a twentieth-century composer (Szymanowski) solved the problem of assimilating typical pianistic patterns of their respective eras in short musical forms, These selections are preceded on the program by a group of compositions, consis- ting of a. a Chaconne for violin solo by J. S. Bach, an eighteenth-century composer, as. transcribed for piano by a twentieth-century composer, who recreated this piece, using all the possibilities of modern piano technique, b. -

Theory of International Politics

Theory of International Politics KENNETH N. WALTZ University of Califo rnia, Berkeley .A yy Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Reading, Massachusetts Menlo Park, California London • Amsterdam Don Mills, Ontario • Sydney Preface This book is in the Addison-Wesley Series in Political Science Theory is fundamental to science, and theories are rooted in ideas. The National Science Foundation was willing to bet on an idea before it could be well explained. The following pages, I hope, justify the Foundation's judgment. Other institu tions helped me along the endless road to theory. In recent years the Institute of International Studies and the Committee on Research at the University of Califor nia, Berkeley, helped finance my work, as the Center for International Affairs at Harvard did earlier. Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and from the Institute for the Study of World Politics enabled me to complete a draft of the manuscript and also to relate problems of international-political theory to wider issues in the philosophy of science. For the latter purpose, the philosophy depart ment of the London School of Economics provided an exciting and friendly envi ronment. Robert Jervis and John Ruggie read my next-to-last draft with care and in sight that would amaze anyone unacquainted with their critical talents. Robert Art and Glenn Snyder also made telling comments. John Cavanagh collected quantities of preliminary data; Stephen Peterson constructed the TabJes found in the Appendix; Harry Hanson compiled the bibliography, and Nacline Zelinski expertly coped with an unrelenting flow of tapes. Through many discussions, mainly with my wife and with graduate students at Brandeis and Berkeley, a number of the points I make were developed. -

Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin's Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowsk

Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin’s Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowski BMUS, University of Victoria, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Music Monika Zaborowski, 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin’s Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowski BMUS, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Susan Lewis-Hammond, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Bruce Vogt, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Michelle Fillion, (School of Music) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Susan Lewis-Hammond, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Bruce Vogt, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Michelle Fillion, (School of Music) Departmental Member One of the major problems faced by performers of Chopin’s mazurkas is recapturing the elements that Chopin drew from Polish folk music. Although scholars from around 1900 exaggerated Chopin’s quotation of Polish folk tunes in their mixed agendas that related ‘Polishness’ to Chopin, many of the rudimentary and more complex elements of Polish folk music are present in his compositions. These elements affect such issues as rhythm and meter, tempo and tempo fluctuation, repetitive motives, undulating melodies, function of I and V harmonies. During his vacations in Szafarnia in the Kujawy region of Central Poland in his late teens, Chopin absorbed aspects of Kujaw performing traditions which served as impulses for his compositions. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

ROUND DANCE BASICS TWO STEP - PHASE I TOUCH, (Action) DIRECTIONS: - Action Touching Free Foot Toe at Supp

ROUND DANCE BASICS TWO STEP - PHASE I TOUCH, (Action) DIRECTIONS: - Action touching free foot toe at supp. foot instep. - Line Of Dance, Reverse Line Of Dance, - Other actions; (STAMP, TAP, HEEL, TOE) - Wall, Center Of Hall. (Diagonals) POINT, (Action) POSITIONS: - Action touching free ft. toe in direction indicated. - Open, Left-Open, Closed, Semi-Closed, - Apart,-, Point,-; Together,-, Touch,-; (Std. Intro.) - Butterfly, Sdcar, and Banjo. TWIRL "N". ASSUMED POSITION: - Man Fwd "n", Lady Twirls Right Face in "n". - In OPEN, if cued to face partner w/o position cue, - Twirl,-,2,-; Apt,-,Pt,-; (Frequent dance ending) - Then assumed position is BUTTERFLY. - In SEMI, if cued to face partner w/o position cue, ******** (HOT TIME MIXER) ******* - Then assumed position is CLOSED. BLENDING: WALK,-, (S) - Graceful transition from one position to another. - A step in line of progression taking 2 beats - In OPEN, blend to SEMI, etc. - Open, Closed, Semi-Closed.... - Other Walking steps; STRUT, STROLL, SWAGGER STARTING FOOTWORK: - WALK "N" - Take "n" walking steps. - Man's Left Foot, Lady's Right Foot. - Lead Foot, Trailing Foot RUN, (Q) - A step in line of progression taking 1 beat FREE FOOT, SUPPORTING FOOT: - RUN "N" - Take "n" running steps. - The foot that has no weight on it is the "Free Foot" - The foot that has weight is the "Supporting Foot". CIRCLE WALK AWAY or TOGETHER "N". - Walk in a circular pattern away/to partner "n" steps. CUEING PRACTICES - Cues are directed to Man's footwork CIRCLE WALK AWAY & TOGETHER;; (SS,SS) - Cues for next series of footwork occur prior to use. - 2 steps away from partner, 2 steps towards partner. -

Trinity Irish Dance Study Guide.Indd

● ● ● ● ● Photo by Lois Greenfield. About the Performance The Performance at a Glance Each of these different elements can be the basis for introducing students to the upcoming performance. Who are the Trinity Irish Dance Company? Trinity Irish Dance Company were formed in 1990 by Mark Howard in an effort to showcase Irish music and dance as an art form. The company is made up of 18- 25 year olds, and has received great critical and popular acclaim from audiences throughout the world. They have performed all over the world, and have collaborated with many notable contemporary choreographers and musicians. Trinity holds a unique place in the dance world, offering a highly skilled presenation of progressive Irish step dance. Who is Mark Howard? Mark Howard is the founder and artistic director of the Trinity Irish Dance Company, and choreographs much of the company’s work. Born in Yorkshire, England, and raised in Chicago, Mark Howard began dancing at the age of nine, and later went on to become a North American champion Irish dancer. He started the Trinity Academy of Irish Dance at the age of 17, and dancers from this school have won 18 world titles for the United States at the World Irish Dance Championships in Ireland. Howard wanted to find a way for his dancers to do more than just compete for tropies and prizes, so in 1990 he founded the Trinity Irish Dance Company as a way to showcase Irish music and dances as an art form. Mark Howard continues to choregraph new works for the company, and he has expanded his independent career to work in theater, television, concert and film. -

Bera Ballroom Dance Club Library

BERA BALLROOM DANCE CLUB LIBRARY Video Instruction DANCE TITLE ARTIST Style LEVEL 1 American Style Exhibition Choreography Cha Cha Powers & Gorchakova VHS Cha Cha 2 American Style Beginning Rumba & Cha Cha Montez VHS Rumba & Cha Beg 3 American Style Intermediate Cha Cha Montez VHS Cha Cha Int 4 American Style Advanced I Cha Cha Montez VHS Cha Cha Adv 5 American Style Advanced II Cha Cha Montez VHS Cha Cha Adv 6 International Style Cha Cha Ballas VHS Cha Cha 10 American Style Beginning Tango Maranto VHS Tango Beg 11 American Style Intermediate Tango Maranto VHS Tango Int 12 American Style Advanced I Tango Ballas VHS Tango Adv 13 American Style Advanced II Tango Maranto VHS American Tango Adv 14 Advanced Tango American Style Techniques & Principles Kloss VHS American Tango Adv 21 Waltz Vol I International Style Technique & Principles Puttock VHS Int Waltz 22 Waltz International Style Standard Technique Veyrasset &Smith VHS Int Waltz 23 American Style Beginning Waltz Maranto VHS Waltz Beg 24 American Style Intermediate Waltz Maranto VHS Waltz Int 25 American Style Advanced I Waltz Maranto VHS Waltz Adv 26 American Style Advanced II Waltz Maranto VHS Waltz Adv 27 Waltz Vol 1 – Beginner Austin VHS Waltz Beg 30 American Style Beginners Viennese Waltz Maranto VHS Viennese Waltz Beg 31 American Style Intermediate Viennese Waltz Maranto VHS Viennese Waltz Int 32 International Style Advanced I Viennese Waltz Veyrasset &Smith VHS Viennese Waltz Adv 33 Viennese Waltz International Style Standard Technique Veyrasset &Smith VHS Int Viennese 40 International -

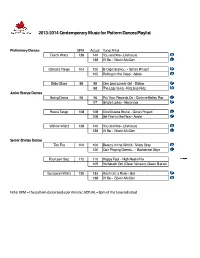

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist Preliminary Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Dut ch Walt z 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Can ast a Tan go 104 100 El Capitalismo... - Gotan Project 105 Rolling in the Deep - Adele Baby Bl ues 88 88 One Less Lonely Girl - Bieber 88 The Lazy Song - Kidz bop Kidz Ju n i o r Br o n z e D a n ce s Sw i n g Da n c e 96 96 Put Your Records On - Corinne Bailey Rae 97 Single Ladies - Beyoncee Fi est a Tango 108 108 Una Musica Brutal - Gotan Project 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele Willow Waltz 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Se ni or Br onze Da nce s Ten Fox 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Fo ur t een St ep 112 110 Happy Feet - High Heels Mix 109 Hollaback Girl (Clean Version)-Gwen Stefani Eu r o p ean Wal t z 135 133 Kiss from a Rose - Seal 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Note: BPM = the pattern dance beats per minute; ACTUAL = bpm of the tune indicated _____________________________________________________________________________________ 2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist pg2 Junior Silver Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Keat s Foxt r ot 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Ro ck er Fo xt r o t 104 104 Black Horse & the Cherry Tree - KT Tunstall 104 Never See Your Face Again- Maroon 5 Harris Tango 108 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele 111 Gotan Project - Queremos Paz American Walt z 198 193 Fal l i n - Al i ci a Keys