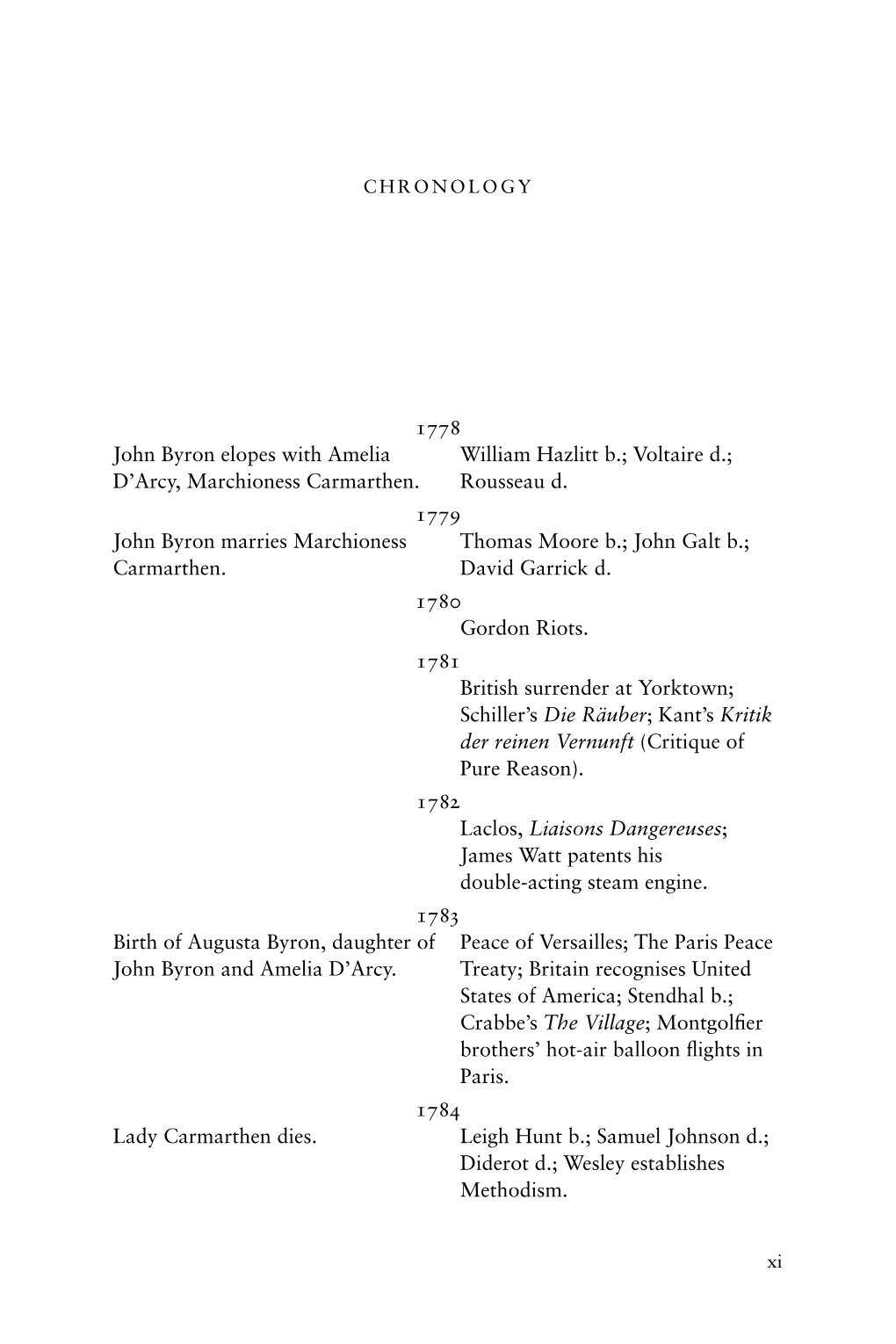

1778 John Byron Elopes with Amelia D'arcy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Order of Authors: Degrees of 'Popularity' and 'Fame' in John Clare's Writing

The Order of Authors: Degrees of ‘Popularity’ and ‘Fame’ in John Clare’s Writing ADAM WHITE Abstract: This essay analyses Clare’s essay ‘Popularity in Authorship’, arguing that the work can be seen as a central statement in Clare’s recurrent concern with poetic fame and authorial reputation. By connecting ‘Popularity in Authorship’ with Clare’s sonnets on his Romantic contemporaries (Robert Bloomfield and Lord Byron), the essay contends that Clare’s complex understanding of ‘popular’ and ‘common’ notions of fame helps to bring into focus a distinctive contribution to debates about how authors were received by different audiences in the period. Contributor: Adam White currently teaches in English and American Studies at the University of Manchester, where he obtained his PhD. He has published a number of essays on Romantic poetry, most recently on Robert Burns and John Clare. In 2012 his essay on Leigh Hunt, John Keats, John Hamilton Reynolds, and John Clare was awarded second prize in the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association competition. For The Literary Encyclopedia he has written entries on Lord Byron, John Keats, the Brontë sisters, Charles Dickens, and Thomas Hardy. In a letter of 29 August 1828 to Thomas Pringle,1 John Clare states that ‘I would sooner be the Author of Tam o shanter then of the Iliad & Odyssey of Homer’ (Storey 437).2 It is intriguing that Clare should voice a bold preference for being the author of ‘Tam o’ Shanter’ given that earlier in his career he had in fact been called ‘a second [Robert] Burns’ (Storey 105) after the instant success of his first volume, Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery (1820). -

BYRON COURTS ANNABELLA MILBANKE, AUGUST 1813-DECEMBER 1814 Edited by Peter Cochran

BYRON COURTS ANNABELLA MILBANKE, AUGUST 1813-DECEMBER 1814 Edited by Peter Cochran If anyone doubts that some people, at least, have a programmed-in tendency to self-destruction, this correspondence should convince them. ———————— Few things are more disturbing (or funnier) than hearing someone being ironical, while pretending to themselves that they aren’t being ironical. The best or worst example is Macbeth, speaking of the witches: Infected be the air whereon they ride, And damned all those that trust them! … seeming unconscious of the fact that he trusts them, and is about to embark, encouraged by their words, on a further career of murder that will end in his death. “When I find ambiguities in your expression,” writes Annabella to Byron on August 6th 1814, “I am certain that they are created by myself, since you evidently desire at all times to be simple and perspicuous”. Annabella (born 1792) is vain, naïve, inexperienced, and “romantic”, but she’s also highly intelligent, and it’s impossible not to suspect that she knows his “ambiguities” are not “created by” herself, and that she recognizes in him someone who is the least “perspicuous” and most given to “ambiguities” who ever lived. The frequency with which both she and she quote Macbeth casually to one another (as well as, in Byron’s letters to Lady Melbourne, Richard III ) seems a subconscious way of signalling that they both know that nothing they’re about will come to good. “ … never yet was such extraordinary behaviour as her’s” is Lady Melbourne’s way of describing Annabella on April 30th 1814: I imagine she’d say the same about Byron. -

Reviews a Congenial Figure

unconventional deist Mary Wollstonecraft, Reviews a congenial figure. A woman writer who did so little to forward the agenda of contemporary feminism was, apparently, best consigned to silence. But by ignoring Anne Stott, Hannah More: The First More, the scholars of this period Victorian. Oxford University Press, postponed the discovery that her 2003. Pp. 384. £25.00. reputation as a sanctimonious conservative ISBN 0199245320. is not fully deserved. More’s first biographer, William Though an important figure in her own Roberts, whose Memoirs of the Life and time, Hannah More (1745-1833) was Correspondence of Mrs. Hannah More ignored by the generation of feminist appeared in the year after her death, bears scholars who began, during the 1970s, to much responsibility for the distorted rediscover forgotten or depreciated picture of More, which, as Stott notes, was women writers. The degree to which these until very recently ‘firmly embedded in scholars overlooked More is revealed by the historiography’ concerning her (p. ix). the fact that no full-length biography Roberts felt free to alter More’s appeared between 1952, when M. G. correspondence to fit his view of the way Jones’s sensible but rather perfunctory that the founding mother of the Hannah More was published, and the Evangelical movement ought to have appearance of Anne Stott’s Hannah More: written. Since few of More’s letters were The First Victorian in 2003. Yet More in print in any other form, Roberts’s was not only the most widely-read British portrait of More became the standard woman writer of her era, the author of picture, but in the early twentieth century plays, conduct books, tracts for the poor, a that picture, which corresponded to its best-selling novel and a variety of creator’s ideal of pious femininity, devotional works, but also a historical appeared less flattering. -

What Are Poets For?

Afterword What Are Poets For? In the last issue of Windfall we called for a “new realistic romanticism, in which the human relation to nature is once again called to account, as well as exalted.” What do we mean by this apparent contradiction in terms, a “realistic romanticism,” and how would it work in writing poetry today? In poetry the term “Romanticism” recalls the movement that took hold at the beginning of the nineteenth century, including German poets such as Goethe, Novalis, and Hölderlin, and English poets such as Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, Keats, and Clare. These poets in general were responding to the rise of the industrial age in Europe, the rationalistic, dehumanizing era characterized by Blake’s “dark Satanic mills.” The Romantic poets asserted the primacy of emotion and a redemptive relation to nature. In terms of writing about nature, Hölderlin produced numerous poems about the rivers of Germany, Keats gave us his “Ode to a Nightingale” and “Ode to Autumn,” and Shelley wrote “Ode to the West Wind.” Wordsworth engaged nature on many levels, most memorably in “Lines Written above Tintern Abbey.” Among Romantic poets, the one whose work dealt most directly with nature was John Clare (1793-1864). Other poets were inclined to idealize nature, and their treatment of it in poetry was often symbolic and literary— Keats’ nightingale was a creature of the imagination, Greek myth, and poetic tradition, not of observation: Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird! No hungry generations tread thee down; The voice -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

1 Byron: Six Poems of Separation

1 Byron: Six Poems of Separation edited by Peter Cochran If one’s marriage were to collapse in humiliating, semi-public circumstances, and if one were in part to blame for its collapse, one’s reaction would probably be to maintain a discreet and (one would hope) a dignified silence, and to hope that the thing might blow over in a year or so. Byron’s reaction was write, and publish, poetry about it while it was still collapsing. The first two of these poems were written in London – the first is to his wife, and the next about and to her friend and confidante Mrs Clermont – before he left England, on Thursday April 25th 1816. The next three were written in Switzerland after his departure, and are addressed to his half-sister Augusta. The last one is again to his wife. They show violent contrasts in style and tone (the Epistle to Augusta is Byron’s first poem in ottava rima), and strange, contrasting aspects of Byron’s nature. That he should wish them published at all is perhaps worrying. The urge to confess without necessarily repenting was, however, deep within him. Fare Thee Well! with its elaborate air of injured innocence, and its implication that Annabella’s reasons for leaving him remain incomprehensible, sorts ill with what we know of his behaviour during the disintegration of their marriage in the latter months of 1815. John Gibson Lockhart was moved, five years later, to protest: … why, then, did you, who are both a gentleman and a nobleman, act upon this the most delicate occasion, in all probability, your life was ever to present, as if you had been neither a nobleman nor a gentleman, but some mere overweeningly conceited poet? 1 Of A Sketch from Private Life , William Gifford, Byron’s “Literary Father”, wrote to Murray: It is a dreadful picture – Caravagio outdone in his own way. -

Manfred Lord Byron (1788–1824)

Manfred Lord Byron (1788–1824) Dramatis Personæ MANFRED CHAMOIS HUNTER ABBOT OF ST. MAURICE MANUEL HERMAN WITCH OF THE ALPS ARIMANES NEMESIS THE DESTINIES SPIRITS, ETC. The scene of the Drama is amongst the Higher Alps—partly in the Castle of Manfred, and partly in the Mountains. ‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.’ Act I Scene I MANFRED alone.—Scene, a Gothic Gallery. Time, Midnight. Manfred THE LAMP must be replenish’d, but even then It will not burn so long as I must watch. My slumbers—if I slumber—are not sleep, But a continuance of enduring thought, 5 Which then I can resist not: in my heart There is a vigil, and these eyes but close To look within; and yet I live, and bear The aspect and the form of breathing men. But grief should be the instructor of the wise; 10 Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most Must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth, The Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life. Philosophy and science, and the springs Of wonder, and the wisdom of the world, 15 I have essay’d, and in my mind there is A power to make these subject to itself— But they avail not: I have done men good, And I have met with good even among men— But this avail’d not: I have had my foes, 20 And none have baffled, many fallen before me— But this avail’d not:—Good, or evil, life, Powers, passions, all I see in other beings, Have been to me as rain unto the sands, Since that all—nameless hour. -

John Clare and the Poetry of His Asylum Years

“I think I have been here long enough”: John Clare and the Poetry of His Asylum Years Anindita Chatterjee Sanskrit College, Kolkata Abstract The paper seeks to explore the condition of a so called mad poet John Clare, (1793-1864) who occupies a marginal place in the history of English literature despite the fact that he was a noted figure in the literary canon when his first book of poems was published. Clare was noted for his rural poetry but strangely enough he gradually went out of fashion. In an age which apotheosized poets and identified them as immensely powerful entities, Clare suffered in silence for twenty seven years in an asylum where he ultimately met with his death. During his confinement he wrote more than 300 poems which survive as glimpses of his traumatic life. Pain sharpened his voice and refined his vision although most of his poems remained unpublished until his death. Modern critics are trying to analyse the asylum poems of Clare which hardly appear as works of a mind out of control. In their structural integrity and coherence of thought they leave us in doubt about notions of sanity and insanity. [Keywords: mad poet, marginal, asylum, confinement, pain, control, insanity] John Clare was introduced to the literary world as a native genius. In the year 1820, the publisher, John Taylor launched Clare into the world as a young Northamptonshire peasant poet a young peasant, a day labourer in husbandry, who has no advantages of education beyond others of his class. In critical investigation of John Clare’s place in the literary canon it is his identity and background that has often acquired greater prominence than his poetry.1 It was his rural background, the fact that he was a farm labourer and poet that evoked curiosity and sympathy and granted him a place of prominence. -

Lady Caroline Lamb and Her Circle

APPENDIX Lady Caroline Lamb and her Circle Who’s Who Bessborough, Lord (3rd Earl). Frederick Ponsonby. Father of Lady Caroline Lamb. Held title of Lord Duncannon until his father, the 2nd Earl, died in 1793. Bessborough, Lady (Countess). Henrietta Frances Spencer Ponsonby. Mother of Lady Caroline and her three brothers, John, Frederick, and William. With her lover, Granville Leveson-Gower, she also had two other children. Bruce, Michael. Acquaintance of Byron’s who had an affair with Lady Caroline after meeting her in Paris in 1816. Bulwer-Lytton, Edward. Novelist and poet, he developed a youthful crush on Lady Caroline and almost became her lover late in her life. Byron, Lord (6th Baron). George Gordon. Poet and political activist, he had many love affairs, including one with Lady Caroline Lamb in 1812, and died helping the Greek revolutionary movement. Byron, Lady. Anne Isabella (“Annabella”) Milbanke. Wife of Lord Byron and cousin of Lady Caroline’s husband, William Lamb. Canis. (see 5th Duke of Devonshire) Cavendish, Georgiana. (Little G, or G) Lady Caroline Lamb’s cousin, the elder daughter of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Later Lady Morpeth. 294 Lady Caroline Lamb Cavendish, Harriet Elizabeth. (Harryo) Lady Caroline Lamb’s cousin, the younger daughter of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Later Lady Granville. Churchill, Susan Spencer. Illegitimate daughter of Harriet Caroline Spencer, a relative of Lady Caroline’s, who became the ward of William and Lady Caroline Lamb. Colburn, Henry. Publisher of Lady Caroline’s most famous novel, Glenarvon (1816). Colburn ran a very active business that published a great quantity of British women’s fiction of the early nineteenth century. -

Lyric Ear: Romantic Poetics of Listening

Lyric Ear: Romantic Poetics of Listening By Claire Marie Stancek A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kevis Goodman, Chair Professor Elisa Tamarkin Professor Ian Duncan Professor David Henkin Summer 2018 1 Abstract Lyric Ear: Romantic Poetics of Listening by Claire Marie Stancek Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Kevis Goodman, Chair My dissertation, Lyric Ear: Romantic Poetics of Listening, turns from a centuries-long critical focus on the “lyric voice” to consider instead what I am calling the lyric ear, or the speaking ear. I offer case studies in four nineteenth-century British and American poets, exploring how each develops poetics of listening that open up authorship, agency, and singularity—into unknown collaboration, receptive action, and multiplicity. By focusing on how lyric constructs the ear, rather than the voice, I argue that poetry expands participation to include bodies, objects, and surroundings that share physical space, rather than simply those who have the agency or the privilege to speak. Although the trope of the speaking ear works differently for each poet, certain characteristics remain constant: 1) the speaking ear involves a description of listening, which goes so far in its intensity or detail that it explicitly or implicitly figures the poem itself as an ear; 2) the construction of the poem-as-ear intensifies into a moment of apparent paradox, in which the actions of the mouth and the ear become interchangeable; 3) the descriptions of listening that extend into imaginations of the poem-as-ear propagate formal repetitions, which in all four chapters include refrain, repetition, and rhyme. -

1 4 Henry Stead Swinish Classics

Pre-print version of chapter 4 in Stead & Hall eds. (2015) Greek and Roman Classics and the British Struggle for Social Reform (Bloomsbury). 4 Henry Stead Swinish classics; or a conservative clash with Cockney culture On 1 November 1790 Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France was published in England. The counter-revolutionary intervention of a Whig politician who had previously championed numerous progressive causes provided an important rallying point for traditionalist thinkers by expressing in plain language their concerns 1 Pre-print version of chapter 4 in Stead & Hall eds. (2015) Greek and Roman Classics and the British Struggle for Social Reform (Bloomsbury). about the social upheaval across the channel. From the viewpoint of pro- revolutionaries, Burke’s Reflections gave shape to the conservative forces they were up against; its publication provoked a ‘pamphlet war’, which included such key radical responses to the Reflections as Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Man (1790) and Tom Paine’s The Rights of Man (1791).1 In Burke’s treatise, he expressed a concern for the fate of French civilisation and its culture, and in so doing coined a term that would haunt his counter-revolutionary campaign. Capping his deliberation about what would happen to French civilisation following the overthrow of its nobility and clergy, which he viewed as the twin guardians of European culture, he wrote, ‘learning will be cast into the mire, and trodden down under the hoofs of a swinish multitude’. This chapter asks what part the Greek and Roman classics played in the cultural war between British reformists and conservatives in the periodical press of the late 1810s and early 1820s. -

Don Juan Study Guide

Don Juan Study Guide © 2017 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary Don Juan is a unique approach to the already popular legend of the philandering womanizer immortalized in literary and operatic works. Byron’s Don Juan, the name comically anglicized to rhyme with “new one” and “true one,” is a passive character, in many ways a victim of predatory women, and more of a picaresque hero in his unwitting roguishness. Not only is he not the seductive, ruthless Don Juan of legend, he is also not a Byronic hero. That role falls more to the narrator of the comic epic, the two characters being more clearly distinguished than in Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. In Beppo: A Venetian Story, Byron discovered the appropriateness of ottava rima to his own particular style and literary needs. This Italian stanzaic form had been exploited in the burlesque tales of Luigi Pulci, Francesco Berni, and Giovanni Battista Casti, but it was John Hookham Frere’s (1817-1818) that revealed to Byron the seriocomic potential for this flexible form in the satirical piece he was planning. The colloquial, conversational style of ottava rima worked well with both the narrative line of Byron’s mock epic and the serious digressions in which Byron rails against tyranny, hypocrisy, cant, sexual repression, and literary mercenaries.