Amended Clumber Spaniel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Water Spaniel

V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 1 American Water Spaniel Breed: American Water Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: United States First recognized by the AKC: 1940 Purpose:This spaniel was an all-around hunting dog, bred to retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground with relative ease. Parent club website: www.americanwaterspanielclub.org Nutritional recommendations: A true Medium-sized hunter and companion, so attention to healthy skin and heart are important. Visit www.royalcanin.us for recommendations for healthy American Water Spaniels. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 2 Brittany Breed: Brittany Group: Sporting Origin: France (Brittany province) First recognized by the AKC: 1934 Purpose:This spaniel was bred to assist hunters by point- ing and retrieving. He also makes a fine companion. Parent club website: www.clubs.akc.org/brit Nutritional recommendations: Visit www.royalcanin.us for innovative recommendations for your Medium- sized Brittany. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 4 Chesapeake Bay Retriever Breed: Chesapeake Bay Retriever Group: Sporting Origin: Mid-Atlantic United States First recognized by the AKC: 1886 Purpose:This American breed was designed to retrieve waterfowl in adverse weather and rough water. Parent club website: www.amchessieclub.org Nutritional recommendation: Keeping a lean body condition, strong bones and joints, and a keen eye are important nutritional factors for this avid retriever. Visit www.royalcanin.us for the most innovative nutritional recommendations for the different life stages of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 5 Clumber Spaniel Breed: Clumber Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: France First recognized by the AKC: 1878 Purpose:This spaniel was bred for hunting quietly in rough and adverse weather. -

Table & Ramp Breeds

Judging Operations Department PO Box 900062 Raleigh, NC 27675-9062 919-816-3570 [email protected] www.akc.org TABLE BREEDS SPORTING NON-SPORTING COCKER SPANIEL ALL AMERICAN ESKIMOS ENGLISH COCKER SPANIEL BICHON FRISE NEDERLANDSE KOOIKERHONDJE BOSTON TERRIER COTON DE TULEAR FRENCH BULLDOG HOUNDS LHASA APSO BASENJI LOWCHEN ALL BEAGLES MINIATURE POODLE PETIT BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN (or Ground) NORWEGIAN LUNDEHUND ALL DACHSHUNDS SCHIPPERKE PORTUGUSE PODENGO PEQUENO SHIBA INU WHIPPET (or Ground or Ramp) TIBETAN SPANIEL TIBETAN TERRIER XOLOITZCUINTLI (Toy and Miniatures) WORKING- NO WORKING BREEDS ON TABLE HERDING CARDIGAN WELSH CORGI TERRIERS MINIATURE AMERICAN SHEPHERD ALL TERRIERS on TABLE, EXCEPT those noted below PEMBROKE WELSH CORGI examined on the GROUND: PULI AIREDALE TERRIER PUMI AMERICAN STAFFORDSHIRE (or Ramp) PYRENEAN SHEPHERD BULL TERRIER SHETLAND SHEEPDOG IRISH TERRIERS (or Ramp) SWEDISH VALLHUND MINI BULL TERRIER (or Table or Ramp) KERRY BLUE TERRIER (or Ramp) FSS/MISCELLANEOUS BREEDS SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER (or Ramp) DANISH-SWEDISH FARMDOG STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER (or Ramp) LANCASHIRE HEELER MUDI (or Ramp) PERUVIAN INCA ORCHID (Small and Medium) TOY - ALL TOY BREEDS ON TABLE RUSSIAN TOY TEDDY ROOSEVELT TERRIER RAMP OPTIONAL BREEDS At the discretion of the judge through all levels of competition including group and Best in Show judging. AMERICAN WATER SPANIEL STANDARD SCHNAUZERS ENTLEBUCHER MOUNTAIN DOG BOYKIN SPANIEL AMERICAN STAFFORDSHIRE FINNISH LAPPHUND ENGLISH SPRINGER SPANIEL IRISH TERRIERS ICELANDIC SHEEPDOGS FIELD SPANIEL KERRY BLUE TERRIER NORWEGIAN BUHUND LAGOTTO ROMAGNOLO MINI BULL TERRIER (Ground/Table) POLISH LOWLAND SHEEPDOG NS DUCK TOLLING RETRIEVER SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER SPANISH WATER DOG WELSH SPRINGER SPANIEL STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER MUDI (Misc.) GRAND BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN FINNISH SPITZ NORRBOTTENSPETS (Misc.) WHIPPET (Ground/Table) BREEDS THAT MUST BE JUDGED ON RAMP Applies to all conformation competition associated with AKC conformation dog shows or at any event at which an AKC conformation title may be earned. -

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally Active and Alert, Sporting Dogs Make Likeable, Well-Rounded Companions

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally active and alert, Sporting dogs make likeable, well-rounded companions. Remarkable for their instincts in water and woods, many of these breeds actively continue to participate in hunting and other field activities. Potential owners of Sporting dogs need to realize that most require regular, invigorating exercise. The breeds of the AKC Sporting Group were all developed to assist hunters of feathered game. These “sporting dogs” (also referred to as gundogs or bird dogs) are subdivided by function—that is, how they hunt. They are spaniels, pointers, setters, retrievers, and the European utility breeds. Of these, spaniels are generally considered the oldest. Early authorities divided the spaniels not by breed but by type: either water spaniels or land spaniels. The land spaniels came to be subdivided by size. The larger types were the “springing spaniel” and the “field spaniel,” and the smaller, which specialized on flushing woodcock, was known as a “cocking spaniel.” ~~How many breeds are in this group? 31~~ 1. American Water Spaniel a. Country of origin: USA (lake country of the upper Midwest) b. Original purpose: retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground c. Other Names: N/A d. Very Brief History: European immigrants who settled near the great lakes depended on the region’s plentiful waterfowl for sustenance. The Irish Water Spaniel, the Curly-Coated Retriever, and the now extinct English Water Spaniel have been mentioned in histories as possible component breeds. e. Coat color/type: solid liver, brown or dark chocolate. A little white on toes and chest is permissible. -

Dog Breeds in Groups

Dog Facts: Dog Breeds & Groups Terrier Group Hound Group A breed is a relatively homogeneous group of animals People familiar with this Most hounds share within a species, developed and maintained by man. All Group invariably comment the common ancestral dogs, impure as well as pure-bred, and several wild cousins on the distinctive terrier trait of being used for such as wolves and foxes, are one family. Each breed was personality. These are feisty, en- hunting. Some use created by man, using selective breeding to get desired ergetic dogs whose sizes range acute scenting powers to follow qualities. The result is an almost unbelievable diversity of from fairly small, as in the Nor- a trail. Others demonstrate a phe- purebred dogs which will, when bred to others of their breed folk, Cairn or West Highland nomenal gift of stamina as they produce their own kind. Through the ages, man designed White Terrier, to the grand Aire- relentlessly run down quarry. dogs that could hunt, guard, or herd according to his needs. dale Terrier. Terriers typically Beyond this, however, generali- The following is the listing of the 7 American Kennel have little tolerance for other zations about hounds are hard Club Groups in which similar breeds are organized. There animals, including other dogs. to come by, since the Group en- are other dog registries, such as the United Kennel Club Their ancestors were bred to compasses quite a diverse lot. (known as the UKC) that lists these and many other breeds hunt and kill vermin. Many con- There are Pharaoh Hounds, Nor- of dogs not recognized by the AKC at present. -

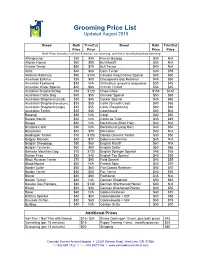

Grooming Price List Updated August 2016

Grooming Price List Updated August 2016 Breed Bath Trim/Cut Breed Bath Trim/Cut Price Price Price Price Bath Price includes: nail trim & dremel, ear cleaning, and minor face/feet/sanitary trimming Affenpincher $30 $45 French Bulldog $30 N/A Afghan Hound $60 $90 Bull Mastiff $55 N/A Airdale Terrier $50 $70 Bull Terrier $40 N/A Akita $40 $60 Cairn Terrier $30 $55 Alaskan Malamute $90 $140 Cavalier King Charles Spaniel $40 $60 American Eskimo $35 $60 Chesapeake Bay Retriever $45 $65 American Foxhound $30 N/A Chihuahua (smooth & longcoated) $30 $45 American Water Spaniel $40 $60 Chinese Crested $33 $45 Anatolian Shepherd Dog $70 $120 Chow Chow $100 $140 Australian Cattle Dog $45 $55 Clumber Spaniel $50 $65 Australian Shepherd (small) $30 $45 Cocker Spaniel $45 $65 Australian Shepherd (medium) $35 $50 Collie (Smooth Coat) $40 $65 Australian Shepherd (large) $40 $55 Collie (RoughCoat) $60 $80 Australian Terrier $30 $45 Coonhound $40 N/A Basengi $35 N/A Corgi $40 $50 Basset Hound $40 N/A Coton de Tular $35 $45 Beagle $30 N/A Dachshund (Short Hair) $40 N/A Bearded Collie $30 N/A Dachshund (Long Hair) $40 $50 Beauceron $40 $70 Dalmation $40 N/A Bedlington Terrier $70 $100 Dandie Dinmont Terrier $30 $50 Belgian Malinois $40 $70 Doberman Pincher $45 N/A Belgian Sheepdog $50 $80 English Mastiff $60 N/A Belgian Tervwren $50 $80 English Setter $50 $65 Bernese Mountain Dog $70 $120 English Springer Spaniel $45 $65 Bichon Frise $35 $45 English Toy Spaniel $40 $55 Black Russian Terrier $70 $90 Field Spaniel $40 $55 Blood Hound $50 N/A Finnish Spitz $40 -

The Cocker Spaniel by Sharon Barnhill

The Cocker Spaniel By Sharon Barnhill Breed standards Size: Shoulder height: 38 - 41 cm (15 - 16.5 inches). Weight is around 29 lbs. Coat: Hair is smooth and medium length. Character: This dog is intelligent, cheerful, lively and affectionate. Temperament: Cocker Spaniels get along well with children, other dogs, and any household pets. Training: Training must be consistent but not overly firm, as the dog is quite willing to learn. Activity: Two or three walks a day are sufficient. However, this breed needs to run freely in the countryside on occasion. Most of them love to swim. Cocker spaniel refers to two modern breeds of dogs of the spaniel dog type: the American Cocker Spaniel and the English Cocker Spaniel, both of which are commonly called simply Cocker Spaniel in their countries of origin. It was also used as a generic term prior to the 20th century for a small hunting Spaniel. Cocker spaniels were originally bred as hunting dogs in the United Kingdom, with the term "cocker" deriving from their use to hunt the Eurasian Woodcock. When the breed was brought to the United States it was bred to a different standard which enabled it to specialize in hunting the American Woodcock. Further physical changes were bred into the cocker in the United States during the early part of the 20th century due to the preferences of breeders. Spaniels were first mentioned in the 14th century by Gaston III of Foix-Béarn in his work the Livre de Chasse. The "cocking" or "cocker spaniel" was first used to refer to a type of field or land spaniel in the 19th century. -

Extended Breed Standard of the Clumber Spaniel from the Australian National Kennel Council

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL KENNEL COUNCIL Extended Breed Standard of THE CLUMBER SPANIEL Produced by Clumber Spaniel League Victoria Inc. in collaboration with the ANKC Standard adopted by Kennel Club, London 1994 Standard adopted by ANKC 1994 – Amended 2005 FCI Standard No: 109 Breed Standard Extension adopted by ANKC 2007 Copyright Australian National Kennel Council 2007 Country of Origin – United Kingdom Extended Standards are compiled purely for the purpose of training Australian judges and students of the breed. In order to comply with copyright requirements of authors, artists and photographers of material used, the contents must not be copied for commercial use or any other purpose. Under no circumstances may the Standard or Extended Standard be placed on the Internet without written permission of the ANKC. “Very different types of Clumber Spaniels have from time to time been exhibited, and although there is a standard of points for judging Clumbers, there is no denying the fact that there are slight differences of opinion as to what should constitute the ideal type of Clumber.” 1 HISTORY OF THE CLUMBER SPANIEL “As a sporting spaniel, it may be said that the Clumber has no equal among the different varieties of spaniels. They certainly may not be quite so flashy in outward appearance to the casual observer, but they are very much sounder in actual work, for once they have been properly broken, they do not easily forget their lesson; they are less headstrong, more honest and conscientious in their perseverance, better game- finders, and although perhaps not as a rule quite so fast in their pace as the more leggy springer, they can be got quite quick enough to satisfy the most fastidious, and, if properly trained in condition, will endure and stay as well as any.” 2 The Clumber Spaniel is the oldest gun/field dog, developed for a specific purpose by sportsmen; in fact the Clumber is one of the oldest named breeds. -

Rae Furness of the Raycroft Clumbers

Rae Furness of the Raycroft Clumbers I’ve been asked to write a few lines on Rae and her dogs. It’s hard to believe that she died as long ago as October, 1993. There must now be a number of present day exhibitors who never knew her but the affix Raycroft still appears in most of the extended pedigrees of today’s dogs. She was born Rachel Lamb in a house situated on the estate of the legendary William Arkwright and was brought up with a Newfoundland, an Airedale, Cairns and her father’s kennel of working gundogs. She left school in 1936 and told her parents much to their disgust, that the only thing she wanted to do was to breed dogs! The breed she chose were Irish Setters. She showed an Irish belonging to her mother’s cousin which did quite well but her sights were always at the top, so her father bought her two bitches from Mrs Baker (Gaeland). Within three years she was winning cc’s. At the same time she also showed a few Pointers and English Setters. Incidentally, Joe Braddon’s first Pointer came from Raycroft, as did Miss Barnes first English Setter. During the war years Rae kept a small kennel of setters which she campaigned as soon as shows resumed. She made up the first post war champion. The trend continued, there have been about forty Raycroft champions in Irish Setters. Eric Furness had his own private pack of Bloodhounds, a very famous line of working springers and a strong kennel of hunt terriers, so when they married in 1951 something had to go, so Rae gave up her English Setters. -

Skillathon Stations: Book 1, Page 12 (Photos from AKC Website) Breed Key

Skillathon stations: Book 1, page 12 (photos from AKC website) Breed Key Terrier Group 1 17 33 Airedale Terrier Parson Russell Terrier Bull Terrier 25 Skye Terrier 16 40 Lakeland Terrier Norwich Terrier Herding Group: Briard 2 Collie 18 34 Shetland Sheepdog 26 Old English 41 German Sheepdog Shepherd 15 Welsh Corgi Working Group: 35 Great Dane 3 Mastiff 19 Standard Schnauzer 27 14 42 Rottweiler German Pinscher Samoyed Toy Group: 48 Chihuahua 4 Maltese 20 Toy Fox Terrier 28 43 13 Pug Toy Poodle Papillon Hound Group: 5 21 36 Bloodhound Borzoi Norwegian Elkhound 29 44 12 Dachshund Whippet Greyhound Miscellaneous Group: 8 24 39 Treeing Walker Coonhound Russell Terrier Chinook 32 47 9 American English Coonhound Norwegian Lundhund Rat Terrier Sporting Group: 6 22 37 English Setter Gordon Setter Weimaraner 30 45 11 Pointer Sussex Spaniel German Shorthaired Pointer Non-Sporting Group: Bichon Frise Dalmatian Chow Chow 7 38 Terrier Working 23 Toy Non-sporting 10 Lhasa Apso Standard Poodle 46 Boston Terrier 31 1. 2. 3. 4. 1a. 2a. 3a. 4a. Senior Senior Senior Senior Herding Hounds Sporting Miscellaneous 5. 6. 7. 8. Senior Senior Senior Senior 5a. 6a. 7a. 8a. Senior Category: Choose a photo of a dog breed. A. Match one dog photo to the correct Dog Breed Group, write the number of the dog photo and B. Identify the dog breed by name in the space below. DOG SKILLATHON - BREED IDENTIFICATION Name: ___________________________Entry #: ___________ Armband: _________ County: ________________________ Team: ____________________ Junior Category Match a photo of dog to correct breed. A. Choose one breed of dog for each Dog Breed Group. -

Best in Grooming Best in Show

Best in Grooming Best in Show crownroyaleltd.net About Us Crown Royale was founded in 1983 when AKC Breeder & Handler Allen Levine asked his friend Nick Scodari, a formulating chemist, to create a line of products that would be breed specific and help the coat to best represent the breed standard. It all began with the Biovite shampoos and Magic Touch grooming sprays which quickly became a hit with show dog professionals. The full line of Crown Royale grooming products followed in Best in Grooming formulas to meet the needs of different coat types. Best in Show Current owner, Cindy Silva, started work in the office in 1996 and soon found herself involved in all aspects of the company. In May 2006, Cindy took full ownership of Crown Royale Ltd., which continues to be a family run business, located in scenic Phillipsburg, NJ. Crown Royale Ltd. continues to bring new, innovative products to professional handlers, groomers and pet owners worldwide. All products are proudly made in the USA with the mission that there is no substitute for quality. Table of Contents About Us . 2 How to use Crown Royale . 3 Grooming Aids . .3 Biovite Shampoos . .4 Shampoos . .5 Conditioners . .6 Finishing, Grooming & Brushing Sprays . .7 Dog Breed & Coat Type . 8-9 Powders . .10 Triple Play Packs . .11 Sporting Dog . .12 Dilution Formulas: Please note when mixing concentrate and storing them for use other than short-term, we recommend mixing with distilled water to keep the formulas as true as possible due to variation in water make-up throughout the USA and international. -

Sample Exam Questions Group 3 (Gundogs)

SAMPLE EXAM QUESTIONS GROUP 3 (GUNDOGS) The following questions are taken from all breeds in Group 3 and provide examples of the types of questions that will appear in the exam papers. 1. The general appearance of the Welsh Springer Spaniel: (a) very compact, athletic rather than racy, quick and active mover (b) symmetrical, compact, active mover displaying plenty of push and drive (c) a well-balanced, square dog; obviously built for endurance and hard work 2. The general appearance of the Golden Retriever: (a) well proportioned, athletic rather than racy, level mover (b) symmetrical, compact, active mover displaying plenty of power (c) symmetrical, balanced, active, powerful, level mover 3. The temperament of the English Setter: (a) loyal and loving companion (b) even tempered, happy and lively disposition (c) intensely friendly and good natured 4. The characteristics of the Labrador Retriever: (a) Good tempered; excellent nose, soft mouth; keen love of water (b) Alert, self-controlled, good natured and biddable (c) A devoted companion dog and versatile hunter To which breed standards do the following refer (Q5 – 7)? Select your answers from the choices provided in the box. 5. Highest on leg and raciest in build of all British land Spaniels. ________________________ Gordon Setter 6. … general outline a series of graceful curves. A strong but lissom Pointer appearance. Irish Setter _________________________ Field Spaniel 7. Must be racy, balanced and full of quality. Weimaraner __________________________ English Springer Spaniel . Circle the correct word(s) to complete the statements: 8. The muzzle of the Irish Water Spaniel is (short / long / broad), strong, somewhat square with a ( gradual / slight / well defined) stop. -

A B C D E F Pricing by Breed

PRICING BY BREED Please choose the closest breed to your pet. If your breed is not listed, please call us at 480.399.3789 for a price quote. A C Affenpinscher $75 Cats (All Breeds) $90 Afghan Hound $120 Canaan Dog $100 Airedale Terrier -Standard $120 Cairn Terrier $75 Airedale Terrier - Minature $85 Cavalier King Charles Spaniel $75 Akita $120 Chesapeake Bay Retriever $100 Alaskan Malamute $130 Chihuahua $65 American English Coonhound $75 Chinese Crested American Eskimo $90 • Hairless $70 American Foxhound $75 • Powder-Puff $70 American Staffordshire Terrier $75 Chinese Shar-Pei $85 American Water Spaniel $85 Chow Chow $110 Anatolian Shepard $90 Clumber Spaniel $85 Australian Cattle Dog $90 Cocker Spaniel $85 Australian Shepherd Coonhound $75 • Full Size $110 Collie $105 • Mini $90 Corgi $80 Australian Terrier $75 Coton De Tulaer $80 Curly-Coated Retriever $100 B Basenji $75 D Basset Hound $75 Dachshund/Dotson $65 Beagle $75 Dalmatian $75 Bearded Collie $120 Dandie Dinmont Terrier $75 Beauceron $85 Doberman Pinscher $75 Bedlington Terrier $80 Dogo Argentino $85 Belgian Malinois $120 Doodle Belgian Sheepdog $120 • Full Size (30+) $110 Belgian Tervuren $120 • Half Size (0-29lbs) $85 Bernese Mountain Dog $140 Bichon Frise $80 Bloodhound $80 E Blue Heeler $100 English Cocker Spaniel $85 Border Collie $110 English Foxhound $75 Border Terrier $75 English Setter $90 Borzoi $110 English Springer Spaniel $90 Boston Terrier $75 English Toy Spaniel $75 Bouvier des Flandres $120 Boxer $75 F Boykin Spaniel $100 Flat-Coated Retriever $110 Briard $100 Brittany $100 Brussels Griffon $80 Bull Dog • American $75 • English $75 • French $70 Bull Terrier $75 PRICING BY BREED Please choose the closest breed to your pet.