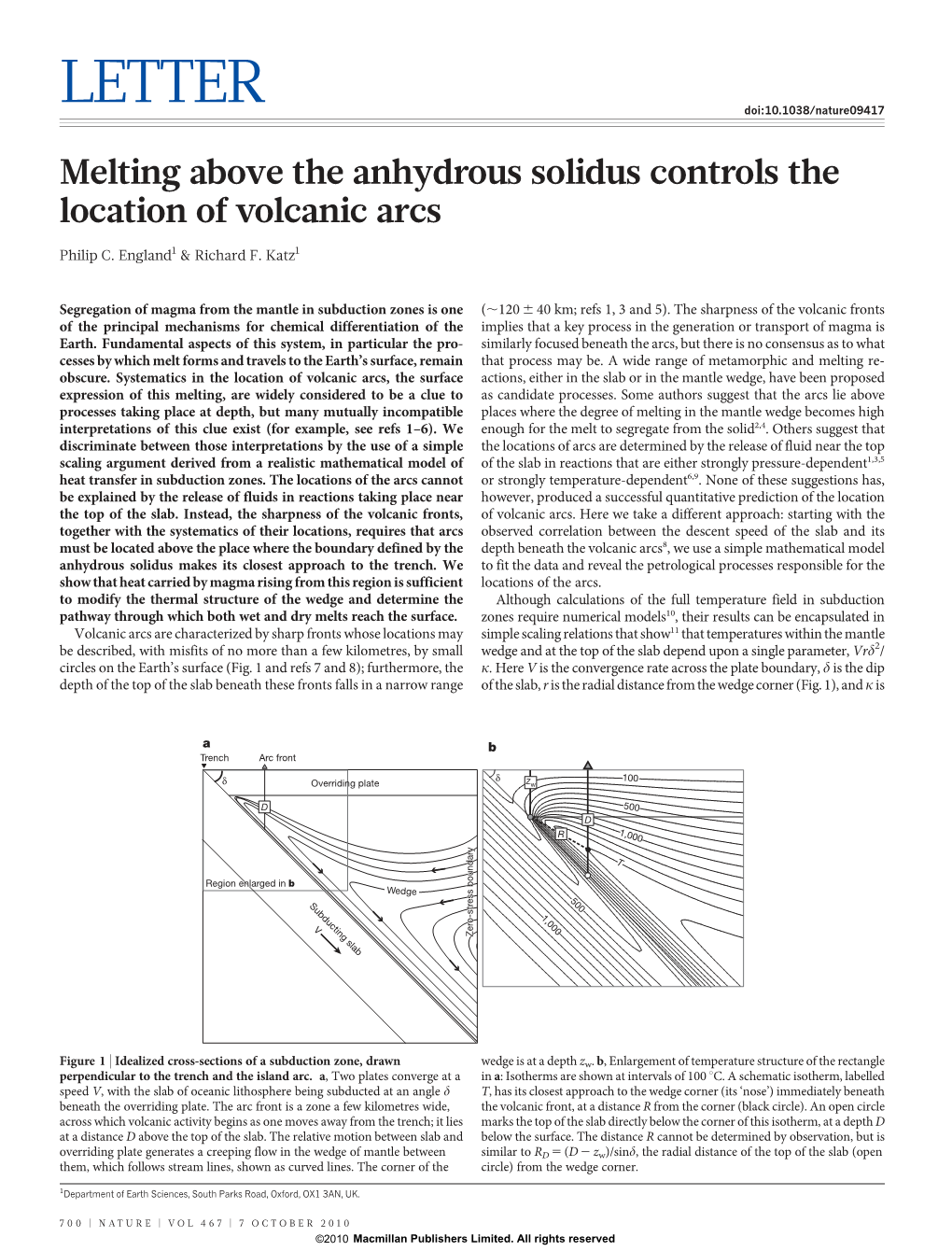

England and Katz, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocean Trench

R E S O U R C E L I B R A R Y E N C Y C L O P E D I C E N T RY Ocean trench Ocean trenches are long, narrow depressions on the seafloor. These chasms are the deepest parts of the ocean—and some of the deepest natural spots on Earth. G R A D E S 5 - 12+ S U B J E C T S Earth Science, Geology, Geography, Physical Geography C O N T E N T S 11 Images, 1 Video, 2 Links For the complete encyclopedic entry with media resources, visit: http://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/ocean-trench/ Ocean trenches are long, narrow depressions on the seafloor. These chasms are the deepest parts of the ocean—and some of the deepest natural spots on Earth. Ocean trenches are found in every ocean basin on the planet, although the deepest ocean trenches ring the Pacific as part of the so-called “Ring of Fire” that also includes active volcanoes and earthquake zones. Ocean trenches are a result of tectonic activity, which describes the movement of the Earth’s lithosphere. In particular, ocean trenches are a feature of convergent plate boundaries, where two or more tectonic plates meet. At many convergent plate boundaries, dense lithosphere melts or slides beneath less-dense lithosphere in a process called subduction, creating a trench. Ocean trenches occupy the deepest layer of the ocean, the hadalpelagic zone. The intense pressure, lack of sunlight, and frigid temperatures of the hadalpelagic zone make ocean trenches some of the most unique habitats on Earth. -

Contrasting Volcano Spacing Along SW Japan Arc Caused by Difference

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Contrasting volcano spacing along SW Japan arc caused by diference in age of subducting lithosphere Yoshiyuki Tatsumi1,2*, Nobuaki Suenaga3, Shoichi Yoshioka2,3, Katsuya Kaneko 1,2 & Takumi Matsumoto4 The SW Japan arc built by subduction of the Philippine Sea (PHS) plate exhibits uneven distribution of volcanoes: thirteen Quaternary composite volcanoes form in the western half of this arc, Kyushu Island, while only two in the eastern half, Chugoku district. Reconstruction of the PHS plate back to 14 Ma, together with examinations based on thermal structure models constrained by high- density heat fow data and a petrological model for dehydration reactions suggest that fuids are discharged actively at depths of 90–100 km in the hydrous layer at the top of the old (> 50 Ma), hence, cold lithosphere sinking beneath Kyushu Island. In contrast, the young (15–25 Ma) oceanic crust downgoing beneath Chugoku district releases fuids largely at shallower depths, i.e. beneath the non- volcanic forearc, to cause characteristic tectonic tremors and low-frequency earthquakes (LFEs) and be the source of specifc brine springs. Much larger amounts of fuids supplied to the magma source region in the western SW Japan arc could build more densely-distributed volcanoes. Subduction zone volcanoes tend to exhibit regular spacing along a volcanic arc, although the spacing of volcanoes within individual arcs is ofen variable from arc to arc1, 2. A broad positive correlation between the linear density of active volcanoes and the rate of plate convergence suggests that the faster subduction contributes to greater melt production in the mantle wedge3–5. -

Mantle Flow Through the Northern Cordilleran Slab Window Revealed by Volcanic Geochemistry

Downloaded from geology.gsapubs.org on February 23, 2011 Mantle fl ow through the Northern Cordilleran slab window revealed by volcanic geochemistry Derek J. Thorkelson*, Julianne K. Madsen, and Christa L. Sluggett Department of Earth Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia V5A 1S6, Canada ABSTRACT 180°W 135°W 90°W 45°W 0° The Northern Cordilleran slab window formed beneath west- ern Canada concurrently with the opening of the Californian slab N 60°N window beneath the southwestern United States, beginning in Late North Oligocene–Miocene time. A database of 3530 analyses from Miocene– American Holocene volcanoes along a 3500-km-long transect, from the north- Juan Vancouver Northern de ern Cascade Arc to the Aleutian Arc, was used to investigate mantle Cordilleran Fuca conditions in the Northern Cordilleran slab window. Using geochemi- Caribbean 30°N Californian Mexico Eurasian cal ratios sensitive to tectonic affi nity, such as Nb/Zr, we show that City and typical volcanic arc compositions in the Cascade and Aleutian sys- Central African American Cocos tems (derived from subduction-hydrated mantle) are separated by an Pacific 0° extensive volcanic fi eld with intraplate compositions (derived from La Paz relatively anhydrous mantle). This chemically defi ned region of intra- South Nazca American plate volcanism is spatially coincident with a geophysical model of 30°S the Northern Cordilleran slab window. We suggest that opening of Santiago the slab window triggered upwelling of anhydrous mantle and dis- Patagonian placement of the hydrous mantle wedge, which had developed during extensive early Cenozoic arc and backarc volcanism in western Can- Scotia Antarctic Antarctic 60°S ada. -

Latitude Volcanoes Dubious Case for Slab Melting in the Northern

Dubious case for slab melting in the Northern volcanic zone of the Andes: Comment and Reply COMMENT Moreover, the SiO2 range of “putative slab melts” is assumed to represent the silica content of primary magmas produced in front of the E. Bourdon Carnegie Ridge. Such an assumption should be valid only if all magmas Department of Geology, Royal Holloway, University of London, represent true primary melts. However, fractional crystallization is an effi - Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK cient process able to strongly modify silica content of magmas (including P. Samaniego in the Northern volcanic zone). Consequently, silica defi nitely appears to Departamento de Geofísica, Escuela Politecnica Nacional, be an inappropriate geochemical feature to distinguish slab melts. AP 17-01-2759, Quito, Ecuador Garrison and Davidson (2003) also argue that the lack of unequivocal M. Monzier, C. Robin, J.-P. Eissen geochemical variation along the arc excludes slab melting. However, data re- IRD, UR 031, Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, Universite Blaise cently presented (Monzier et al., 2003) show systematic geochemical varia- Pascal, 5 rue Kessler, 63038 Clermont-Ferrand, France tion along the arc, all showing a negative or positive peak between 0.5°N and H. Martin 1°S. Among those, Y and La/Yb display clear minimums and maximums, UMR 6524, Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, Universite Blaise Pascal, respectively, precisely where the Carnegie Ridge is subducting (Fig. 1). Such 5 rue Kessler, 63038 Clermont-Ferrand, France behavior refl ects the intervention of slab melts in the petrogenesis of the magmas, directly related to the subduction of the Carnegie Ridge. Recently, Garrison and Davidson (2003) questioned the possibility We agree with the Garrison and Davidson (2003) conclusion that that the adakites of the Northern volcanic zone of the Andes were gener- the magma geochemical signature characterizes the source and not any ated by slab melting. -

Andean Flat-Slab Subduction Through Time

Andean flat-slab subduction through time VICTOR A. RAMOS & ANDRE´ S FOLGUERA* Laboratorio de Tecto´nica Andina, Universidad de Buenos Aires – CONICET *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The analysis of magmatic distribution, basin formation, tectonic evolution and structural styles of different segments of the Andes shows that most of the Andes have experienced a stage of flat subduction. Evidence is presented here for a wide range of regions throughout the Andes, including the three present flat-slab segments (Pampean, Peruvian, Bucaramanga), three incipient flat-slab segments (‘Carnegie’, Guan˜acos, ‘Tehuantepec’), three older and no longer active Cenozoic flat-slab segments (Altiplano, Puna, Payenia), and an inferred Palaeozoic flat- slab segment (Early Permian ‘San Rafael’). Based on the present characteristics of the Pampean flat slab, combined with the Peruvian and Bucaramanga segments, a pattern of geological processes can be attributed to slab shallowing and steepening. This pattern permits recognition of other older Cenozoic subhorizontal subduction zones throughout the Andes. Based on crustal thickness, two different settings of slab steepening are proposed. Slab steepening under thick crust leads to dela- mination, basaltic underplating, lower crustal melting, extension and widespread rhyolitic volcan- ism, as seen in the caldera formation and huge ignimbritic fields of the Altiplano and Puna segments. On the other hand, when steepening affects thin crust, extension and extensive within-plate basaltic flows reach the surface, forming large volcanic provinces, such as Payenia in the southern Andes. This last case has very limited crustal melt along the axial part of the Andean roots, which shows incipient delamination. -

Geochemical Evidence for Slab Melting in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt

JOURNAL OF PETROLOGY VOLUME 48 NUMBER 3 PAGES 537^562 2007 doi:10.1093/petrology/egl071 Geochemical Evidence for Slab Melting in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt ARTURO GO¤MEZ-TUENA1*, CHARLES H. LANGMUIR2, STEVEN L. GOLDSTEIN3, SUSANNE M. STRAUB3 AND FERNANDO ORTEGA-GUTIE¤RREZ4 1CENTRO DE GEOCIENCIAS, UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTO¤ NOMA DE ME¤ XICO, QUERE¤ TARO 76230, MEXICO 2DEPARTMENT OF EARTH AND PLANETARY SCIENCES, HARVARD UNIVERSITY, CAMBRIDGE, MA 02138, USA 3LAMONT^DOHERTY EARTH OBSERVATORY AND DEPARTMENT OF EARTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, 61 RT. 9W, PALISADES, NY 10964, USA 4INSTITUTO DE GEOLOGI¤ A, UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTO¤ NOMA DE ME¤ XICO, CIUDAD UNIVERSITARIA, MEXICO CITY 04510, MEXICO RECEIVED MARCH 17, 2006; ACCEPTED NOVEMBER 2, 2006; ADVANCE ACCESS PUBLICATION DECEMBER 26, 2006 Geochemical studies of Plio-Quaternary volcanic rocks from theValle KEY WORDS: arcs; mantle; Mexico; sediment melting; slab melting de Bravo^Zita¤cuaro volcanic field (VBZ) in central Mexico indi- cate that slab melting plays a key role in the petrogenesis of theTrans- Mexican Volcanic Belt. Rocks from the VBZ are typical arc-related INTRODUCTION high-Mg andesites, but two different rock suites with distinct trace Slab-derived fluxing plays an important role in the element patterns and isotopic compositions erupted concurrently in global geochemical cycle, and gives rise to the distinctive the area, with a trace element character that is also distinct from chemical compositions observed in arc magmas (Gill, that of other Mexican -

Ocean Trenches a Computer Animation and Paper Model by Tau Rho Alpha*, and John P

Go Home U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Ocean Trenches A computer animation and paper model By Tau Rho Alpha*, and John P. Galloway* Open-file Report 96-76A This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this program has been used by the U.S. Geological Survey, no warranty, expressed or implied, is made by the USGS as to the accuracy and functioning of the program and related program material, nor shall the fact of distribution constitute any such warranty, and no responsibility is assumed by the USGS in connection therewith. *U.S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, CA 94025 Comments encouraged [email protected] [email protected] o (go backward) < I l> (go forward) Description of Report This report illustrates, by means of computer animations and a paper model, how a subduction zone works. By studying the animations and the paper model, students will better understand the processes that operate at converging margins between tectonic plates and how ocean trenches and the volcanoes associated with them are developed. Included in the paper and diskette versions of this report are templates for making the paper model, instructions for its assembly, a discussion of the lithosphere, asthenosphere, earth's plates, plate boundaries, and only in the diskette version, animations of sea-floor spreading. Many people provided help and encouragement in the development of this HyperCard stack, particularly Art Ford and Tracy Vallier. -

A Geothermal System Associated with the Most Recent Volcanic Eruption in Romania

TUSNAD-BAI - A GEOTHERMAL SYSTEM ASSOCIATED WITH THE MOST RECENT VOLCANIC ERUPTION IN ROMANIA Horia Mitrofan Societatea Nationala a Apelor Minerale, str. Mendeleev 36-38, Bucuresti, Romania Key Words: volcanic environment, geothermometer, exception). After 1990, evidence of late Quaternary eruptions has Tusnad-Bai, Romania been, however, identified also for Ciomadul volcano, in the South Harghita mountains, in Romania. The long known hydrothermal ABSTRACT surface manifestations situated nearby provide, under this new perspective, indications of a geothermal system possibly related to Carbon dating (14C) ages ranging between 10,700 and a still cooling pluton. >42,650 years BP have been reported by various investigators for organic matter (charcoal fragments Consequently, an assessment procedure specifically devised for included in a pumice flow deposit; paleosoil underlying geothermal resources associated with active volcanic areas the pumice deposit) from Ciomadul volcano, next to (Hochstein, 1990) was adopted. Intensive use was made of the Na- Tusnad-Bai. This is the most recent volcanic eruption in K-Mg geothermometry (Giggenbach, 1986, 1988), corroborated Romania documented to date, and it implies the existence with former investigation results. of a still active magma chamber, with which a high temperature (>225°C) geothermal system might be associated. The most significant hydrothermal activity in 2. STUDY AREA the area consists of a lineament of springs that discharge about 5 kg/s (aggegate flow rate) of sodium chloride 2.1. Volcanologic setting thermal water which is CO2 rich, relatively low in TDS (1.5-4.5 g/l), and has a maximum temperature of 23oC. The East Carpathian mountains include a Neogene-Quaternary The Na-K geothermometer indicates that the spring waters volcanic arc, related to a complex collisional pattern between the could have originated from a hot (≈300oC) reservoir of Eurasian and the African plates. -

The Onset of the Volcanism in the Ciomadul Volcanic Dome Complex (Eastern Carpathians): Eruption Chronology and Magma Type Variation

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 354 (2018) 39–56 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jvolgeores The onset of the volcanism in the Ciomadul Volcanic Dome Complex (Eastern Carpathians): Eruption chronology and magma type variation Kata Molnár a,⁎, Szabolcs Harangi a,b, Réka Lukács b,IstvánDunklc, Axel K. Schmitt d, Balázs Kiss b, Tamás Garamhegyi e,IoanSeghedif a Department of Petrology and Geochemistry, Eötvös Loránd University, Pázmány Péter stny. 1/c, H-1117 Budapest, Hungary b MTA-ELTE Volcanology Research Group, Budapest, Hungary c Sedimentology and Environmental Geology, Geoscience Centre, Georg-August University, Göttingen, Germany d Institute of Earth Sciences, Ruprecht-Karls University, Heidelberg, Germany e Department of Physical and Applied Geology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary f Institute of Geodynamics, Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Romania article info abstract Article history: Combined zircon U-Th-Pb and (U-Th)/He dating was applied to refine the eruption chronology of the last 2 Myr Received 29 June 2017 for the andesitic and dacitic Pilişca volcano and Ciomadul Volcanic Dome Complex (CVDC), the youngest volcanic Received in revised form 9 January 2018 area of the Carpathian-Pannonian region, located in the southernmost Harghita, eastern-central Europe. The pro- Accepted 29 January 2018 posed eruption ages, which are supported also by the youngest zircon crystallization ages, are much younger Available online 3 February 2018 than the previously determined K/Ar ages. By dating every known eruption center in the CVDC, repose times be- Keywords: tween eruptive events were also accurately determined. Eruption of the andesite at Murgul Mare (1865 ± 87 ka) ş Zircon (U-Th)/He dating and dacite of the Pili ca volcanic complex (1640 ± 37 ka) terminated an earlier pulse of volcanic activity within Eruption chronology the southernmost Harghita region, west of the Olt valley. -

1. Slab Surface Temperatures Beneath Volcanic Arcs

Article Volume 13, Number 3 31 March 2012 Q03024, doi:10.1029/2011GC003902 ISSN: 1525-2027 Global variations in H2O/Ce: 1. Slab surface temperatures beneath volcanic arcs Lauren B. Cooper Department of Mineralogy, University of Geneva, CH-1205 Geneva, Switzerland ([email protected]) Institute for Geochemistry and Petrology, ETH-Zurich, CH-8029 Zurich, Switzerland Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA Daniel M. Ruscitto Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York 12180, USA Terry Plank Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA Paul J. Wallace Department of Geological Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403, USA Ellen M. Syracuse Department of Geoscience, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA Craig E. Manning Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA [1] We have calculated slab fluid temperatures for 51 volcanoes in 10 subduction zones using the newly developed H2O/Ce thermometer. The slab fluid compositions were calculated from arc eruptives, using melt inclusion-based H2O contents, and were corrected for background mantle contributions. The temperatures, adjusted to h, the vertical depth to the slab beneath the volcanic arc, range from 730 to 900C and agree well (within 30C on average for each arc) with sub-arc slab surface temperatures predicted by recent thermal models. The coherence between slab model and surface observation implies predominantly vertical transport of fluids within the mantle wedge. Slab surface temperatures are well reconciled with the thermal parameter (the product of slab age and vertical descent rate) and h. -

Causes and Consequences of Flat Slab Subduction in Southern Peru

Crustal structure of north Peru from analysis of teleseismic receiver functions Item Type Article Authors Condori, Cristobal; França, George S.; Tavera, Hernando J.; Albuquerque, Diogo F.; Bishop, Brandon T.; Beck, Susan L. Citation Crustal structure of north Peru from analysis of teleseismic receiver functions 2017, 76:11 Journal of South American Earth Sciences DOI 10.1016/j.jsames.2017.02.006 Publisher PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD Journal Journal of South American Earth Sciences Rights © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Download date 27/09/2021 18:23:19 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final accepted manuscript Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/625974 Causes and consequences of flat slab subduction in southern Peru Brandon T. Bishop1, Susan L. Beck1, George Zandt1, Lara Wagner2, Maureen Long3, Sanja Knezevic Antonijevic4, Abhash Kumar5, Hernando Tavera6 1Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, 1040 East 4th Street, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA 2Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution for Science, 5241 Broad Branch Road NW, Washington DC 20015, USA 3Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, 210 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, Connecticut 06511, USA 4University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB #3312, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 27599, USA 5National Energy Technology Laboratory, 626 Cochrans Mill Road, Pittsburgh, PA 15236, USA 6Instituto Geofísico del Perú, Calle Badajoz 169, Lima 15012, Peru ABSTRACT Flat or near horizontal subduction of oceanic lithosphere has been an important tectonic process both currently and in the geologic past. Subduction of the aseismic Nazca Ridge beneath South America has been associated with the onset of flat subduction and the termination of arc volcanism in Peru, making it an ideal place to study flat slab subduction. -

Pacific Plate Slab Pull and Intraplate Deformation in the Early Cenozoic

Solid Earth, 5, 757–777, 2014 www.solid-earth.net/5/757/2014/ doi:10.5194/se-5-757-2014 © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Pacific plate slab pull and intraplate deformation in the early Cenozoic N. P. Butterworth1, R. D. Müller1, L. Quevedo1, J. M. O’Connor2, K. Hoernle3, and G. Morra4 1EarthByte Group, School of Geosciences, The University of Sydney, New South Wales, 2006, Australia 2GeoZentrum Nordbayern, Erlangen and Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany 3GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Germany 4Department of Physics and School of Geosciences, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 70504, LA, USA Correspondence to: N. P. Butterworth ([email protected]) Received: 22 December 2013 – Published in Solid Earth Discuss.: 14 January 2014 Revised: 4 June 2014 – Accepted: 10 June 2014 – Published: 6 August 2014 Abstract. Large tectonic plates are known to be suscepti- sion between 62 and 42 Ma could cause late-stage volcan- ble to internal deformation, leading to a range of phenom- ism along the Musicians volcanic ridges. Our models demon- ena including intraplate volcanism. However, the space and strate that early Cenozoic changes in Pacific plate driving time dependence of intraplate deformation and its relation- forces only cause relatively minor changes in Pacific abso- ship with changing plate boundary configurations, subduct- lute plate motion directions, and cannot be responsible for ing slab geometries, and absolute plate motion is poorly un- the Hawaiian–Emperor bend (HEB), confirming previous in- derstood. We utilise a buoyancy-driven Stokes flow solver, terpretations that the 47 Ma HEB does not primarily reflect BEM-Earth, to investigate the contribution of subducting an absolute plate motion event.