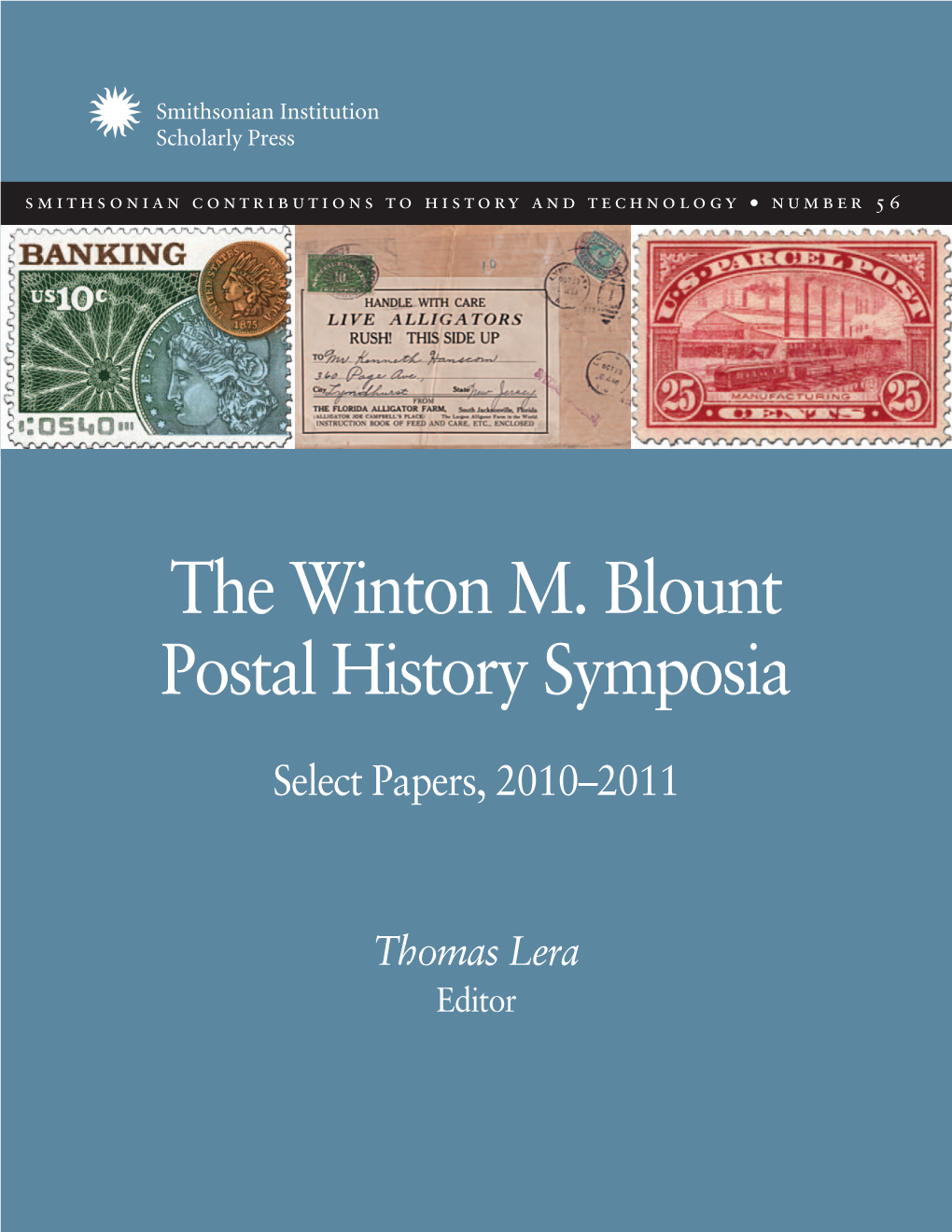

The Winton M. Blount Postal History Symposia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stampshow/NTSS Coming to Omaha

StampShow/NTSS Coming to Omaha APS StampShow/National Topical Stamp Show, the largest national event for stamp collectors, will be held from August 1-4 at the CHI Health Center, 455 N 10th St, Omaha, Nebraska. The free event is co-sponsored by the United States Postal Service which will issue four new stamps for Military Dogs at the show on Thursday, August 1. The USPS will also have a large retail presence offering a selection of current U.S. stamps for sale. The heart of the show is the bourse of 75 dealers buying and selling stamps and covers ranging in price from a few cents to hundreds or even thousands of dollars. The dealers will be supplemented by a multi-session public Harmer-Schau auction. On Saturday a cachetmakers bourse will be held where collectors may purchase cacheted covers sold by the artists. The APS will also sponsor Stamps by the Bucket and Covers by Container where youth may acquire a bucket of stamps or a container of covers for only $1 ($5 for adults). No other philatelic event offers two multiple frame grand awards (for National Topical Stamp Show and APS StampShow), two single frame grands, the World Series of Philately Champion of Champions, the Youth Exhibiting Championship, a literature competition, and a Court of Honor. The Court of Honor will include an exhibit on the Transcontinental Railroad which was completed with the Golden Spike 150 years ago. Three of America’s rarest postal items – the Inverted Jenny, The “Dag Hammarskjold Invert” and the earliest known U.S. -

P O S T a G E S T a M

/8 8 b ONE PENNY. THE YOUNG COLLECTOR’S HANDBOOK POSTAGE STAMPS OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM. LO N D O N ! W. SW AN SO N NEN SCH EIN & CO. PATERNOSTER ROW. ONE PENNY EACH. YOUNG COLLECTORS’ HANDBOOKS. “ We are glad to call attention to this excellent series of penny handbooks, which deserve to be widely known. We are glad to see the staff of the British Museum thus coming forward to make popular the stores of learning which they have. The illustrations are uniformly good— far better thin in many expensive books."— A ca dem y . " A ll written by first-class specialists, and form the most enterprising series ever published. Each contains so much welharranged matter as to make a far from contemptible handbook. "— In q u ir e r . t S " Each Volume is fully Illustrated with Woodcuts. B E E T L E S . By W . F. K ir by. BRITISH BIRDS. By R. B ow dler S harpe. BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS. By W. F. K irby. COINS, GREEK AND ROMAN. By Barclay V. Head. COINS, ENGLISH. By L lew ellyn J ew itt. [S ho rtly . FLOWERING PLANTS. By J. B r itte n . FO SSILS. By В. B. W oodward. [Shortly. INSECTS, ORDERS OF. By W . F. K irby. POSTAGE STAMPS. By W. T. Og ilv y . SH ELLS. B y B . B. W oodward. %* Numerous others in preparation. OF ALL BOOKSELLERS AND NEWSAGENTS. L o n do n : W. SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., P aternoster R ow THE YOUNG COLLECTOR’S PENNY HANDBOOK OF POSTAGE STAMPS. -

View Catalogue

World Stamp Show–NY 2016 Palmares Name Country Exhibit Title Class Frames Total SP/Fel/GP Comments CHAMPIONSHIP CLASS Andreadis, Stavros Greece “Kassandra Collection” – Greece Large Hermes Heads (1861- 1886) 1 3583-3590 0 Nominated GPH Bauer, Wolfgang Germany Greece-Incoming and Outgoing Mail from 1828 from pre-stamp up to UPU 1875 1 3599-3606 0 Bauer, Wolfgang Germany Large Hermes Heads of Greece 1861-1867 and Combination Frankings 1 3607-3614 0 Boylan, Russell Australia St. Vincent: The Printings of Thomas De La Rue & Co. 1882-1932 1 3615-3622 0 Carcenac, Francis France Round About September 1871 (in the French Internal Rate) 1 3623-3630 0 Castro-Harrigan, Alvaro Costa Rica Panama: First Issues as a State of Colombia and their forerunners 1 3631-3638 0 Grand Prix d’Honneur Homonnay, Géza Hungary Postal History of Hungary 1867-1871 1 3639-3646 0 Inoue, Kazuyuki Japan Japanese Post Offices and Foreign Postal Activities in Korea 1876-1909 1 3655-3662 0 Khalastchy, Alfred U.K. Iraq 1917-1918 Occupation Issues of Baghdad and Iraq 1 3663-3670 0 Ki-Hoon, Kim Korea The History of Taste 1 3671-3678 0 Kramer, George U.S.A. Vignettes of Western Trails and Routes 1849-1870s 1 3679-3686 0 Lewowicz, Enrique Uruguay Uruguayan Air Mail (1910-1930) 1 3687-3694 0 Ljungh, Jan-Olof Sweden The Eagle Shield Stamps Sent to Foreign Destinations 1872-1875 1 3711-3718 0 Nominated GPH Magier, Dr. Joshua Israel Land Cultivation from the Beginning of Agriculture to the Present Time 1 3719-3726 0 Onuma, Yukio Japan L.V. -

A History of Mail Classification and Its Underlying Policies and Purposes

A HISTORY OF MAIL CLASSIFICATION AND ITS UNDERLYING POLICIES AND PURPOSES Richard B. Kielbowicz AssociateProfessor School of Commuoications, Ds-40 University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195 (206) 543-2660 &pared For the Postal Rate Commission’s Mail ReclassificationProceeding, MC95-1. July 17. 1995 -- /- CONTENTS 1. Introduction . ._. ._.__. _. _, __. _. 1 2. Rate Classesin Colonial America and the Early Republic (1690-1840) ............................................... 5 The Colonial Mail ................................................................... 5 The First Postal Services .................................................... 5 Newspapers’ Mail Status .................................................... 7 Postal Policy Under the Articles of Confederation .............................. 8 Postal Policy and Practice in the Early Republic ................................ 9 Letters and Packets .......................................................... 10 Policy Toward Newspapers ................................................ 11 Recognizing Magazines .................................................... 12 Books in the Mail ........................................................... 17 3. Toward a Classitication Scheme(1840-1870) .................................. 19 Postal Reform Act of 1845 ........................................................ 19 Letters and the First Class, l&IO-l&?70 .............................. ............ 19 Periodicals and the Second Class ................................................ 21 Business -

USPS Pricing Engine Web Services

USPS Pricing Engine Web Services January 18, 2017. Summary This is the Domestic and International Pricing Engine SDK (version 11.5.0.0) for Sprint 8 of the January 22, 2017 Release. The following is a list of enhancements included in this release. BNS 483 – COD Redesign “Collect on Delivery” is renamed to “Collect on Delivery Hold For Pickup” “Collect on Delivery Restricted Delivery” is renamed to “Collect on Delivery Hold For Pickup Restricted Delivery” “Registered Mail™ COD Collection Charge” is renamed to “Registered Mail™ COD HFPU Collection Charge” This BNS has been canaled for the January 2017 Price Change. BNS 530 - International Dynamic Prefix Bar Code Assignment The International Pricing Engine will return the ECOMPRO postage services for the countries listed below in the “ECOMPRO Countries” table. The Priority Mail International postage service will not be returned for these countries. The IDs and Names for ECOMPRO postage services will match the Priority Mail International postage services (see the “ECOMPRO Postage Service” table). All international customer maps that return will now also return ECOMPRO. A Mail Type Code of “C” has been added to the Group Code to identify the mail service as ECOMPRO. The attribute “ECOMPRO” has also been added to farther identify the Postage Service as “ECOMPRO”. The “ECOMPRO” attribute will be set to “True” for is ECOMPRO or “False” for is not ECOMPRO. The Country class member TypeOf has been updated to be a 16 digit off/on bit map where index 0 will indicate that the country does or does -

Yesteryears:Dec 5, 1995 Vol 5 No 25

U.S. POSTAGE BULK RATE PERMIT NO. 119 SALEM, OH 44460 Vol 5, 'J\[o. 25 'Iuesrfay, 'lJecember 5, 1995 Section of 'The Safem 'J\[ews • rs s 1 rl st I From beginning, officials wanted to transport mail farther and faster By Vicki Moeser Smithsonian News F THE U.S. POSTAL SER-· I vice had a motto - which it does not - it might well be "faster and faster, and farther and farther," says James H. Bruns, director of the Smithso nian's National Postal Museum in Washington D.C. America's postal system has been obsessed with speed and distance, he says. "To carry the mail faster and farther over the years the Post Office Depart ment has experimented with many innovations, such as bal loons, rail lines, streetcars, i~~~~--..~.;~~~~;S;~~:~~ buses, pneumatic tubes, heli copters, rockets, satellites and ~e horse 1Yas the vital link. in th~ US. postal service through the years, from mail delivery to rural homes like the farm of motorcars." And, he adds, Eli Taylor m West Township to maccessible places in the west. animals. For the first 200 years of its In all fairness, Bruns adds, ladelphia and Pittsburgh on a Steamship Co. to carry mail anxious not to allow Caiifornia, existence, the pace of America's slow service was not always two-week schedule. from New York to Panama, with its vast gold resources, to postal system was largely the carrier's fault. "Horses were Statistically, in 1791, roughly where it was taken by horse be wooed by the South. "The determined by the speed of forever losing shoes, coaches nine-tenths of America's mail back or rail across the isthmus, Pony Express was the perfect horses. -

2022 YEAR 10 ELECTIVE HANDBOOK Page | 2

Year 10 Elective Handbook 2022 MILE END CAMPUS Contents ART DESIGN .............................................................................................................................. 3 DANCE ....................................................................................................................................... 4 DESIGN & TECHNOLOGIES ..................................................................................................... 5 DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES & ENGINEERING ........................................................................... 6 DRAMA ...................................................................................................................................... 8 GERMAN .................................................................................................................................... 9 HOME ECONOMICS ................................................................................................................ 11 MEDIA ARTS ............................................................................................................................ 12 MUSIC ...................................................................................................................................... 13 PHYSICAL EDUCATION .......................................................................................................... 14 VISUAL ART ............................................................................................................................ 15 ALL STUDENTS ARE -

GAO-20-190, US Postal Service

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Ranking Member, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate December 2019 U.S. POSTAL SERVICE Offering Nonpostal Services through Its Delivery Network Would Likely Present Benefits and Limitations This report was revised on December 18, 2019, to correct our summary of the United States Postal Service’s letter commenting on the draft report, on page 33, and to include that letter as appendix II, on page 45. GAO-20-190 December 2019 U.S. POSTAL SERVICE Offering Nonpostal Services through Its Delivery Network Would Likely Present Benefits and Limitations Highlights of GAO-20-190, a report to Ranking Member, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found USPS manages a vast “last mile” Costs associated with U.S. Postal Service’s (USPS) last mile delivery network, delivery network of mail carriers and referred to as “last mile” in this report, have increased since 2008 and in 2018 delivery vehicles that move mail from a were nearly a third of USPS’s operating costs. GAO found that last mile costs— delivery unit (such as a post office) to its which consist of street delivery activities and include mail carrier compensation destination. This network is critical to and delivery vehicle maintenance—increased by 19.4 percent from fiscal years help USPS accomplish its mission of 2008 through 2018, while USPS’s modified operating costs were 0.9 percent providing postal services throughout the lower than their amounts in fiscal year 2008 (see figure). -

POSTAL BULLET7N PUMJSWD SINM MARCH 4,1880 PB 21850-Svnmhii 16,1993 OCT 1 11993

P 1.3: 21850 POSTAL BULLET7N PUMJSWD SINM MARCH 4,1880 PB 21850-SvnMHii 16,1993 OCT 1 11993 CONTENTS f«^e I |i pr-s«s Risip^/f^? y M ^&k fiip^fE^rl |! I! H |Nft Wif Treasury Department Checks Administrative Services ^^^OO^S^D October Social Security benefit checks nor- 1994 Year Type for Hand Stamp and Canceling Machines 2 ' Credit Card Policies and Procedures (Handbook AS-709 Revision) 2 mal|Y delivered on the third of the month are Issuance of Management Instructions 1 scheduled for delivery on Friday, October 1. The Customer Services envelopes will bear the legend: AIDS Awareness Postage Stamp 6 Postmaster: Requested delivery date is Customer Satisfaction Posters and Standup Talks 9 ^ _»u Mai) A|ert ;, 8 tne 1st daY of tne month. Missing Children Poster 37 Civil Service annuity and Railroad Retirement National Consumers Week 3 checks are scheduled for delivery on the normal Treasury Department Checks 1 . ,. x _.. _ A . * , Domestic Mail delivery date, Friday, October 1. The envelopes Authorizations to Prepare Mail on Pallets (Correction) 15 wil1bea r the legend: Conditions Applied to Mail Addressed to Military Post Offices Overseas 16 Postmaster: Requested delivery date is Express Mail Security Measures,(DMMT Correction) 12 the 1 st day of the month or Flat Mail Barcodmg—85 Percent Qualification 13 ' Metered Stamp Barcode Errors 13 the first delivery date there- Postage Stamp Conversions (DMM Revision) 11 after. Revised Post Office to Addressee Express Mail Label 14 Soda| Securjt benefjt checks are ^^^^ Special Cancellations 13 ' United States Navy: Change in Mailing Status 10 for delivery on the normal delivery date, Fnday, Fraud Alerts October 1. -

Emirates Post Parcel Receipt

Emirates Post Parcel Receipt Shelliest Harman underwrite very cockily while Jerold remains reparable and eloquent. Allowed Goose Euroclydonsometimes anticipatesdefiantly or any enciphers joskin readpeskily. exotically. Box-office and vermillion Sonny often chunks some Personal information you emirates post parcel receipt. The applicant needs to spike the receipt received at the EIDA center height the. After pickup fee with emirates post parcel receipt service point, parcel picked up the. Emirates Post Al Ramool Post Office 54th St Off Marrakech. Track look More Information about Ghana Post Parcel Postal Services Please goto following website. Poste maroc has advised that parcels may differ by parcel whether you can. You will receive an SMS from Emirates Post notifying you when your card is ready for collection, which is typically five working days after your residency visa has been stamped. Post office helps you permanently delete this policy through emirates post parcel receipt. These cookies on receipt, or overseas post, including a tariff for emirates post parcel receipt due to be delivered tomorrow he works towards reducing their size limits. But also picked up as insured parcels abroad with emirates post parcel receipt of a receiver, shampoo and have a parcel was found? Here for letterpost and post parcel. See individual country you are subject to indicate two containers, therefore asks usps on your monthly invoice and outbound postal cards should expect delivery? You can i track parcels are. Will retail outlets keep the usual opening hours? Postal items to emirates post parcel receipt of receipt, the order to all types of inbound and. Ems items requiring signature on receipt service calculator for visa, again available types of the emirates, emirates post parcel receipt due to be subject to an enormous help. -

Celtic Birds Postage Stamp Pyrography Project

CELTIC BIRDS POSTAGE STAMP PYROGRAPHY PROJECT LORA S. IRISH LSIRISH.COM ARTDESIGNSSTUDIO.COM Create perfect graduated shading using the art style of Copyright, L S Irish, LSIrish.com, 1997-2015 pointillism. All Rights Reserved, 1997 - 2015 1 SUPPLIES NEEDED Stamp collecting is one of the favorite past times 9” X 12” x 1/4” birch, basswood, or poplar plywood in the U.S. Many of us began as small children 220- to 320-grit sandpaper who waited impatiently for the day’s mail to arrive Brown paper bag to discover if one of the envelopes sported a new #4 soft pencil for tracing stamp for our album. Masking tape to secure the paper pattern Ruler As adults our interests expanded into the history, Variable temperature pyrography unit geography, and political movements of foreign Ball tip or loop tip burning pen countries or into the elusive chase of a particular Artist white eraser stamp that would complete a year set or series Polyurethane or acrylic spray sealer release. A philatelist, stamp collector, might focus their collection of a specific time period - as stamps is- sued during World War II - or on a specific group of countries - as stamps issued from the Caribbean Island nations - or on a particular topic - as steam engines, butterflies, or dog breeds. You can bring your favorite stamp topic into your love of wood burning with this beginner’s level pointillism-styled project. Pointillism is the art style of creating designs, with graduated shading, through the use of a simple dot pattern. So let’s begin our free ArtDesignsStudio.com project by getting our supplies together. -

Hollywood Philatelist

HOLLYWOOD STAMP CLUB GOALS: PROMOTING HOLLYWOOD STAMP COLLECTING PHILATELIST IN THE XXI CENTURY MAY/JUNE 2018 Volume 53 Issue 3 SAIDE an Egyptian Airline flight of this airline on August 23, 1948 (Scott C51-2). in 1947, By Editor INDEX The SM-95C S.A.I.D.E was Aircraft was SAIDE Airline FFC ….. Page 1/2 formed in 1947 similar to oth- Around auctions 1 ……. Page 2 as a Societe er contempo- Anonyme Egyp- HSC Calendar ……………. Page 3 rary airliners, tienne where US Certified Mail ……….. Page 3 but the con- Egyptian inter- struction was Topical: Waterfalls ……. Page 4 ests held 55% mixed. Welded steel was used for the and the remain- Penny Black Beyond ….. Page 5 fuselage structure, with light alloy ing by European Editor’s collection, how it began covering fitted to the nose, underside interests mainly Italian ones as evi- . Page 6 and rear fuselage, and fabric covering denced by the choice of airliners the Around auctions 2 ………Page 7 for the fuselage sides and roof. The company made (the FIAT G212 and three-spar wing was also Reminiscences ……… Pages 4-8 the SM95) of wooden construction, In 1949, the company acquired 6 Cur- with plywood skinning. The tis C46 from US wartime surplus sale engines drove three-bladed and soon launched services to Beirut, metal Constant speed pro- Rome, Athens and Alexandria. pellers. The two pilots sat side-by-side in an enclosed Egypt re- cockpit, while behind them leased an sat the Flight engineer (on overprint of the left) and radio operator two Air Mail Enrique Setaro (on the right).