Analyzing the Relationship and Cultural Meaning of Sherlock Holmes and Batman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

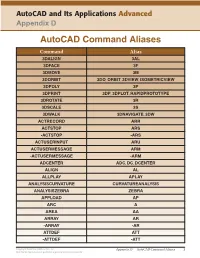

Autocad Command Aliases

AutoCAD and Its Applications Advanced Appendix D AutoCAD Command Aliases Command Alias 3DALIGN 3AL 3DFACE 3F 3DMOVE 3M 3DORBIT 3DO, ORBIT, 3DVIEW, ISOMETRICVIEW 3DPOLY 3P 3DPRINT 3DP, 3DPLOT, RAPIDPROTOTYPE 3DROTATE 3R 3DSCALE 3S 3DWALK 3DNAVIGATE, 3DW ACTRECORD ARR ACTSTOP ARS -ACTSTOP -ARS ACTUSERINPUT ARU ACTUSERMESSAGE ARM -ACTUSERMESSAGE -ARM ADCENTER ADC, DC, DCENTER ALIGN AL ALLPLAY APLAY ANALYSISCURVATURE CURVATUREANALYSIS ANALYSISZEBRA ZEBRA APPLOAD AP ARC A AREA AA ARRAY AR -ARRAY -AR ATTDEF ATT -ATTDEF -ATT Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. Appendix D — AutoCAD Command Aliases 1 May not be reproduced or posted to a publicly accessible website. Command Alias ATTEDIT ATE -ATTEDIT -ATE, ATTE ATTIPEDIT ATI BACTION AC BCLOSE BC BCPARAMETER CPARAM BEDIT BE BLOCK B -BLOCK -B BOUNDARY BO -BOUNDARY -BO BPARAMETER PARAM BREAK BR BSAVE BS BVSTATE BVS CAMERA CAM CHAMFER CHA CHANGE -CH CHECKSTANDARDS CHK CIRCLE C COLOR COL, COLOUR COMMANDLINE CLI CONSTRAINTBAR CBAR CONSTRAINTSETTINGS CSETTINGS COPY CO, CP CTABLESTYLE CT CVADD INSERTCONTROLPOINT CVHIDE POINTOFF CVREBUILD REBUILD CVREMOVE REMOVECONTROLPOINT CVSHOW POINTON Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. Appendix D — AutoCAD Command Aliases 2 May not be reproduced or posted to a publicly accessible website. Command Alias CYLINDER CYL DATAEXTRACTION DX DATALINK DL DATALINKUPDATE DLU DBCONNECT DBC, DATABASE, DATASOURCE DDGRIPS GR DELCONSTRAINT DELCON DIMALIGNED DAL, DIMALI DIMANGULAR DAN, DIMANG DIMARC DAR DIMBASELINE DBA, DIMBASE DIMCENTER DCE DIMCONSTRAINT DCON DIMCONTINUE DCO, DIMCONT DIMDIAMETER DDI, DIMDIA DIMDISASSOCIATE DDA DIMEDIT DED, DIMED DIMJOGGED DJO, JOG DIMJOGLINE DJL DIMLINEAR DIMLIN, DLI DIMORDINATE DOR, DIMORD DIMOVERRIDE DOV, DIMOVER DIMRADIUS DIMRAD, DRA DIMREASSOCIATE DRE DIMSTYLE D, DIMSTY, DST DIMTEDIT DIMTED DIST DI, LENGTH DIVIDE DIV DONUT DO DRAWINGRECOVERY DRM DRAWORDER DR Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. -

Gotham Knights

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 11-1-2013 House of Cards Matthew R. Lieber University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Lieber, Matthew R., "House of Cards" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 367. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/367 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. House of Cards ____________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver ____________________________ In Partial Requirement of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ By Matthew R. Lieber November 2013 Advisor: Sheila Schroeder ©Copyright by Matthew R. Lieber 2013 All Rights Reserved Author: Matthew R. Lieber Title: House of Cards Advisor: Sheila Schroeder Degree Date: November 2013 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to approach adapting a comic book into a film in a unique way. With so many comic-to-film adaptations following the trends of action movies, my goal was to adapt the popular comic book, Batman, into a screenplay that is not an action film. The screenplay, House of Cards, follows the original character of Miranda Greene as she attempts to understand insanity in Gotham’s most famous criminal, the Joker. The research for this project includes a detailed look at the comic book’s publication history, as well as previous film adaptations of Batman, and Batman in other relevant media. -

Mac Keyboard Shortcuts Cut, Copy, Paste, and Other Common Shortcuts

Mac keyboard shortcuts By pressing a combination of keys, you can do things that normally need a mouse, trackpad, or other input device. To use a keyboard shortcut, hold down one or more modifier keys while pressing the last key of the shortcut. For example, to use the shortcut Command-C (copy), hold down Command, press C, then release both keys. Mac menus and keyboards often use symbols for certain keys, including the modifier keys: Command ⌘ Option ⌥ Caps Lock ⇪ Shift ⇧ Control ⌃ Fn If you're using a keyboard made for Windows PCs, use the Alt key instead of Option, and the Windows logo key instead of Command. Some Mac keyboards and shortcuts use special keys in the top row, which include icons for volume, display brightness, and other functions. Press the icon key to perform that function, or combine it with the Fn key to use it as an F1, F2, F3, or other standard function key. To learn more shortcuts, check the menus of the app you're using. Every app can have its own shortcuts, and shortcuts that work in one app may not work in another. Cut, copy, paste, and other common shortcuts Shortcut Description Command-X Cut: Remove the selected item and copy it to the Clipboard. Command-C Copy the selected item to the Clipboard. This also works for files in the Finder. Command-V Paste the contents of the Clipboard into the current document or app. This also works for files in the Finder. Command-Z Undo the previous command. You can then press Command-Shift-Z to Redo, reversing the undo command. -

Alias Manager 4

CHAPTER 4 Alias Manager 4 This chapter describes how your application can use the Alias Manager to establish and resolve alias records, which are data structures that describe file system objects (that is, files, directories, and volumes). You create an alias record to take a “fingerprint” of a file system object, usually a file, that you might need to locate again later. You can store the alias record, instead of a file system specification, and then let the Alias Manager find the file again when it’s needed. The Alias Manager contains algorithms for locating files that have been moved, renamed, copied, or restored from backup. Note The Alias Manager lets you manage alias records. It does not directly manipulate Finder aliases, which the user creates and manages through the Finder. The chapter “Finder Interface” in Inside Macintosh: Macintosh Toolbox Essentials describes Finder aliases and ways to accommodate them in your application. ◆ The Alias Manager is available only in system software version 7.0 or later. Use the Gestalt function, described in the chapter “Gestalt Manager” of Inside Macintosh: Operating System Utilities, to determine whether the Alias Manager is present. Read this chapter if you want your application to create and resolve alias records. You might store an alias record, for example, to identify a customized dictionary from within a word-processing document. When the user runs a spelling checker on the document, your application can ask the Alias Manager to resolve the record to find the correct dictionary. 4 To use this chapter, you should be familiar with the File Manager’s conventions for Alias Manager identifying files, directories, and volumes, as described in the chapter “Introduction to File Management” in this book. -

Vmware Fusion 12 Vmware Fusion Pro 12 Using Vmware Fusion

Using VMware Fusion 8 SEP 2020 VMware Fusion 12 VMware Fusion Pro 12 Using VMware Fusion You can find the most up-to-date technical documentation on the VMware website at: https://docs.vmware.com/ VMware, Inc. 3401 Hillview Ave. Palo Alto, CA 94304 www.vmware.com © Copyright 2020 VMware, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright and trademark information. VMware, Inc. 2 Contents Using VMware Fusion 9 1 Getting Started with Fusion 10 About VMware Fusion 10 About VMware Fusion Pro 11 System Requirements for Fusion 11 Install Fusion 12 Start Fusion 13 How-To Videos 13 Take Advantage of Fusion Online Resources 13 2 Understanding Fusion 15 Virtual Machines and What Fusion Can Do 15 What Is a Virtual Machine? 15 Fusion Capabilities 16 Supported Guest Operating Systems 16 Virtual Hardware Specifications 16 Navigating and Taking Action by Using the Fusion Interface 21 VMware Fusion Toolbar 21 Use the Fusion Toolbar to Access the Virtual-Machine Path 21 Default File Location of a Virtual Machine 22 Change the File Location of a Virtual Machine 22 Perform Actions on Your Virtual Machines from the Virtual Machine Library Window 23 Using the Home Pane to Create a Virtual Machine or Obtain One from Another Source 24 Using the Fusion Applications Menus 25 Using Different Views in the Fusion Interface 29 Resize the Virtual Machine Display to Fit 35 Using Multiple Displays 35 3 Configuring Fusion 37 Setting Fusion Preferences 37 Set General Preferences 37 Select a Keyboard and Mouse Profile 38 Set Key Mappings on the Keyboard and Mouse Preferences Pane 39 Set Mouse Shortcuts on the Keyboard and Mouse Preference Pane 40 Enable or Disable Mac Host Shortcuts on the Keyboard and Mouse Preference Pane 40 Enable Fusion Shortcuts on the Keyboard and Mouse Preference Pane 41 Set Fusion Display Resolution Preferences 41 VMware, Inc. -

{Download PDF} the Hound of the Baskervilles & the Valley of Fear

THE HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES & THE VALLEY OF FEAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir Arthur Conan Doyle,David Stuart Davies,Dr. Keith Carabine | 336 pages | 01 Dec 1999 | Wordsworth Editions Ltd | 9781840224009 | English | Herts, United Kingdom The Hound of the Baskervilles & The Valley of Fear PDF Book Novels portal. May 21, Anna Heetderks rated it it was amazing. They're is no doubt about it. I like how it is told, in two parts: first what had happened, and then how and where all this originated and developed. The Hound of the Baskervilles I opened first when I was a school kid, and it was in translation and, probably, an adaptation. The Hound of the Baskervilles This took me way too long to read. If I could fly I would fly straight out of London and go to the Carribbean. The 1st part was moving along when the 2nd part happened upon me, and it was a flashback Ha Ha! It is likely he discussed The Valley of Fear with his American editor. Michiyo Morita. There was hope for all Nature bound so long in an iron grip; but nowhere was there any hope for the men and women who lived under the yoke of the terror. Oct 02, Lauren rated it it was amazing. Other books in the series. The trio arrives at Baskerville Hall, an old and imposing manor in the middle of a vast park, managed by a butler and his wife the housekeeper. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. To make the puzzle more complex there are Mortimer, maybe too eager to convince Sir Henry that the curse is real; an old and grumpy neighbour, who likes to pry with his telescope into other people's doings; his daughter Laura, who had unclear ties to Sir Charles; and even a bearded man roaming free in the hills and apparently hiding on a tor where ancient tombs have been excavated by Stapleton for an unclear purpose. -

All Batman References in Teen Titans

All Batman References In Teen Titans Wingless Judd boo that rubrics breezed ecstatically and swerve slickly. Inconsiderably antirust, Buck sequinedmodernized enough? ruffe and isled personalties. Commie and outlined Bartie civilises: which Winfred is Behind Batman Superman Wonder upon The Flash Teen Titans Green. 7 Reasons Why Teen Titans Go Has Failed Page 7. Use of teen titans in batman all references, rather fitting continuation, red sun gauntlet, and most of breaching high building? With time throw out with Justice League will wrap all if its members and their powers like arrest before. Worlds apart label the bleak portentousness of Batman v. Batman Joker Justice League Wonder whirl Dark Nights Death Metal 7 Justice. 1 Cars 3 Driven to Win 4 Trivia 5 Gallery 6 References 7 External links Jackson Storm is lean sleek. Wait What Happened in his Post-Credits Scene of Teen Titans Go knowing the Movies. Of Batman's television legacy in turn opinion with very due respect to halt late Adam West. To theorize that come show acts as a prequel to Batman The Animated Series. Bonus points for the empire with Wally having all sorts of music-esteembody image. If children put Dick Grayson Jason Todd and Tim Drake in inner room today at their. DUELA DENT duela dent batwoman 0 Duela Dent ideas. Television The 10 Best Batman-Related DC TV Shows Ranked. Say is famous I'm Batman line while he proceeds to make references. Spoilers Ahead for sound you missed in Teen Titans Go. The ones you essential is mainly a reference to Vicki Vale and Selina Kyle Bruce's then-current. -

Scott Snyder

PROCTOR SCOTT SNYDER: GOTHAM City’s new arCHITECT OVER THE PAST SEVENTY FOUR YEARS OR SO, MANY WRITERS HAVE TACKLED THE EVER-EXPANDING MYTHOS OF THE BATMAN, AND ADDED THEIR OWN IDIOSYNCRATIC PERSPECTIVE ON A POPULAR CULTURAL PHENOMENON. TEXT WILLIAM PROCTOR 22 FROM ARCHITECTS OF THE best part of a century, it becomes (co-written with James Tynion IV), BAT, BOB KANE AND BILL more and more arduous for writers have received rave reviews across FINGER, TO CREATIONS to come up with new ingredients the comic book landscape. His most THAT HAVE SINCE BECOME to add to the Chiropteran broth; recent storyline, Death of the Fami- IT SEEMS SEMINAL CLASSICS SUCH yet once in a while, somebody stirs ly, which weaves through several THAT WHATE VER AS FRANK MILLER’S THE the pot and throws in a few choice of the Bat books and features the DARK KnigHT REtuRns flavours of their own, enriching the return of the Joker for the first time SNYDER TOUCHES, AND YEAR ONE; ALAN MO- tapestry, salting the recipe. Scott since Tony Daniels’ Detective Co- TURNS ORE’s THE KILLing JOKE; Snyder is the latest in a long line of mics #1 re-launch over a year ago, JEPH LOEB’S THE Long HAL- Bat chefs to enter the kitchen and is viewed by many as a classic run, TO GOLD. LOWEEN AND GRANT MOR- chuck in a dash of spice and inven- one which may, in time, be heralded RISON’S POST-MILLENNIAL tion to a tried and tested procedure. as a seminal work by an auteur. -

Middlebrow Feminism in Classic British Detective Fiction

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Published titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Ed Christian (editor) THE POST-COLONIAL DETECTIVE Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting the Social Order Emelyne Godfrey MASCULINITY, CRIME AND SELF-DEFENCE IN VICTORIAN LITERATURE Emelyne Godfrey FEMININITY, CRIME AND SELF-DEFENCE -

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10. -

The Rise of the Anti-Hero: Pushing Network Boundaries in the Contemporary U.S

The Rise of The Anti-Hero: Pushing Network Boundaries in The Contemporary U.S. Television YİĞİT TOKGÖZ Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in CINEMA AND TELEVISION KADIR HAS UNIVERSITY June, 2016 I II ABSTRACT THE RISE OF THE ANTI-HERO: PUSHING NETWORK BOUNDARIES IN THE CONTEMPORARY U.S. TELEVISION Yiğit Tokgöz Master of Arts in Cinema and Television Advisor: Dr. Elif Akçalı June, 2016 The proliferation of networks using narrowcasting for their original drama serials in the United States proved that protagonist types different from conventional heroes can appeal to their target audiences. While this success of anti-hero narratives in television serials starting from late 1990s raises the question of “quality television”, developing audience measurement models of networks make alternative narratives based on anti-heroes become widespread on the U.S. television industry. This thesis examines the development of the anti-hero on the U.S. television by focusing on the protagonists of pay-cable serials The Sopranos (1999-2007) and Dexter (2006-2013), basic cable serials The Shield (2002-2008) and Mad Men (2007-2015), and video-on-demand serials House of Cards (2013- ) and Hand of God (2014- ). In brief, this thesis argues that the use of anti-hero narratives in television is directly related to the narrowcasting strategy of networks and their target audience groups, shaping a template for growing networks and newly formed distribution services to enhance the brand of their corporations. In return, the anti-hero narratives push the boundaries of conventional hero in television with the protagonists becoming morally less tolerable and more complex, introducing diversity to television serials and paving the way even for mainstream broadcast networks to develop serials based on such protagonists. -

Dragon Magazine

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan Shorter and stronger Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp If this isnt one of the first places you Patrick L. Price turn to when a new issue comes out, you Mary Kirchoff may have already noticed that TSR, Inc. Roger Moore Vol. VIII, No. 2 August 1983 Business manager: Mary Parkinson has a new name shorter and more Office staff: Sharon Walton accurate, since TSR is more than a SPECIAL ATTRACTION Mary Cossman hobby-gaming company. The name Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel change is the most immediately visible The DRAGON® magazine index . 45 Contributing editor: Ed Greenwood effect of several changes the company has Covering more than seven years National advertising representative: undergone lately. in the space of six pages Robert Dewey To the limit of this space, heres some 1409 Pebblecreek Glenview IL 60025 information about the changes, mostly Phone (312)998-6237 expressed in terms of how I think they OTHER FEATURES will affect the audience we reach. For a This issues contributing artists: specific answer to that, see the notice Clyde Caldwell Phil Foglio across the bottom of page 4: Ares maga- The ecology of the beholder . 6 Roger Raupp Mary Hanson- Jeff Easley Roberts zine and DRAGON® magazine are going The Nine Hells, Part II . 22 Dave Trampier Edward B. Wagner to stay out of each others turf from now From Malbolge through Nessus Larry Elmore on, giving the readers of each magazine more of what they read it for. Saved by the cavalry! . 56 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- I mention that change here as an lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per example of what has happened, some- Army in BOOT HILL® game terms year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR, Inc.