The Israelite Tabernacle at Shiloh Two Twentieth-Century Excavations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

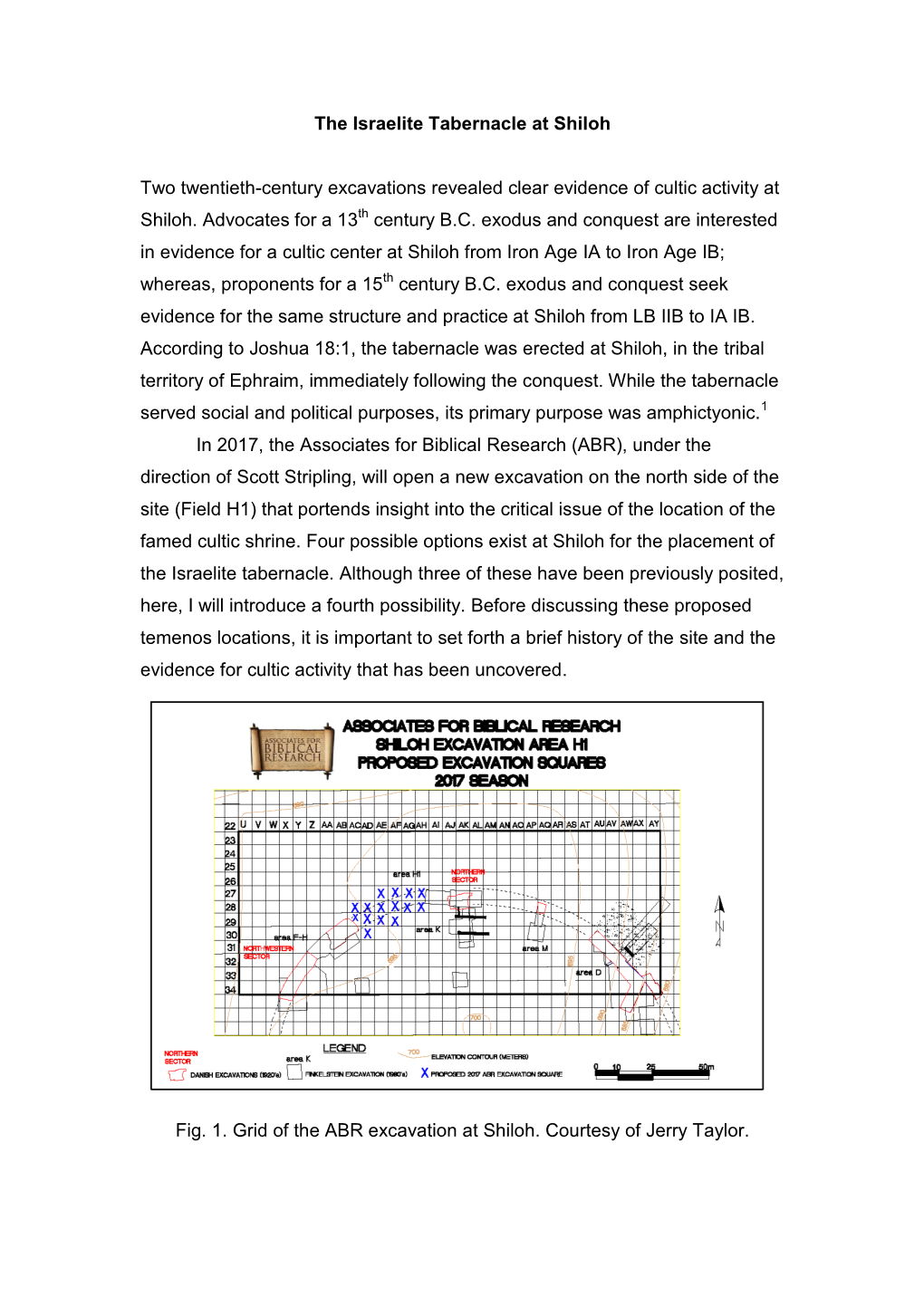

The Israelite Tabernacle at Shiloh

Bibliography and Endnotes for The Israelite Tabernacle at Shiloh Fall 2016 Bible and Spade Bibliography Buhl, Marie-Louise and Holm-Nielson, Svend. Shiloh, The Pre-Hellenistic Remains: The Danish Excavations at Tell Sailun, Palestine, in 1926, 1929, 1932 and 1963. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark and Aarhus University Press (1969). Chapman, R.L. and Taylor, J.E. “Distances Used by Eusebius and the Identification of Sites.” In The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea: Palestine in the Fourth Century AD, eds. G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville and J.E. Taylor, trans. G.S.P. Freedman-Grenville. Jerusalem: Carta (2003), pp. 175–78. Driver, Samuel R. “Shiloh.” In A Dictionary of the Bible: Dealing with Its Language, Literature and Contents Including the Biblical Theology , eds. James Hastings and John A. Selbie. Vol. 4. New York, NY: Scribner’s Sons (1911), pp. 499–500. Notes 1 Use of this term does not imply support for Martin Noth’s views on the emergence of early Israel. Rather, it denotes a confederation of ancient tribes for military conquest or protection and worship of a common deity. 2 Like all excavations in the West Bank, this project will be conducted in cooperation with, and under the auspices of, the Staff Officer of the Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria. 3 For dates through the Persian Period, I follow Bryant Wood’s chronology: “The Archaeological Ages and Old Testament History.” Available at http://www. biblearchaeology.org/file.axd?file=2016%2f7%2fArchaeological+ages+handout+Wood+ 2016.pdf. For later time periods, I use generally accepted dates. 4 MB III witnessed a proliferation of fortification systems at numerous Levantine sites. -

New Early Eighth-Century B.C. Earthquake Evidence at Tel Gezer: Archaeological, Geological, and Literary Indications and Correlations

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 1992 New Early Eighth-century B.C. Earthquake Evidence at Tel Gezer: Archaeological, Geological, and Literary Indications and Correlations Michael Gerald Hasel Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Hasel, Michael Gerald, "New Early Eighth-century B.C. Earthquake Evidence at Tel Gezer: Archaeological, Geological, and Literary Indications and Correlations" (1992). Master's Theses. 41. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

THE VICTORY at AI Joshua 8:1-29 in Joshua 8, God Gives the Children Of

THE VICTORY AT AI Though the primary cause of defeat the first time around was sin...a Joshua 8:1-29 secondary cause was underestimating the enemy (Joshua 7:3-4). In Joshua 8, God gives the children of Israel a second chance, this time I have given into your hand the king of Ai, his people, his city, to do things His way in the taking of the city of Ai. The momentum and his land (vs. 1b)...The defeat of Ai has been assured. God Israel had achieved by the miraculous crossing of the Jordan and the promised to turn the place of defeat into a place of victory. supernatural victory over Jericho was stopped by their defeat at Ai. You shall take only its spoil and its cattle as plunder for your- But one must always remember that Israel was defeated...not because selves (vs. 2b)...Before the actual battle plan was revealed to Joshua they were out manned...they were defeated because of sin. As a result he was told that the spoil of Ai, along with its livestock, could be of their defeat, despair permeated, not only among all those in the camp, taken. Jericho had been placed under the ban...Ai was not. but also within the heart of Joshua (Joshua 7:5). What an irony. If only Achan hadn’t been so greedy and selfish and Now with Achan’s sin judged, God’s favor toward Israel was restored had obeyed God...and had just waited on God...he would have had (Galatians 6:1) and He reassured Joshua that He had not forsaken him all his heart would have desired...and he would have had God’s or His people. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Yearly Worship and Despair at Shiloh

FAITH AND DEDICATION 1 Samuel 1:1-28 Episode 2: 1 Samuel 1:3-8 Yearly Worship and Despair at Shiloh LITERAL TRANSLATION TEXT (Biblia Hebraica) 3aAnd-he-went-up this man from-his-city wry(m )whh #$y)h hl(w3a from-days to-days hmymy Mymym to-bow-down and-to-sacrifice xbzlw twxt#$hl to-the-LORD of-hosts in-Shiloh. ..hl#$b tw)bc hwhyl 3band-there two-of sons-of-Eli yl(-ynb yn#$ M#$w3b Hophni and-Phinehas sxnpw ynpx priests to-the-LORD. .hwhyl Mynxk 4aAnd-it-came the-day when-sacrificed Elkanah hnql) xbzyw Mwyh yhyw4a 4bto-Peninnah his-wife he-customarily-gave Ntnw wt#$) hnnpl4b and-to-all-her-sons and-to-her-daughters hytwnbw hynb-lklw portions. .twnm 5aBut-to-Hannah he-customarily-would-give Nty hnxlw5a portion one face Myp) tx) hnm 5bbecause Hannah he-loved bh) hnx-t) yk5b 5calthough-the-LORD had-closed her-womb. .hmxr rns hwhyw5c 6aAnd-she-would-provoke-her her-rival htrc hts(kw6a indeed fiercely in-order to-humiliate-her hm(rh rwb(b s(k-Mg 6bfor-He-closed the-LORD hwhy rgs-yk6b completely her-womb. .hmxr d(b 7aAnd-this it-would-be-done year by-year hn#$b hn#$ h#(y Nkw7a 7bwhenever her-to-go-up in-the-house tybb htl( ydm7b of-the-LORD then-she-would-provoke-her hns(kt Nk hwhy 7cso-she-would-weep and-not she-would-eat. .lk)t )lw hkbtw7c 8aThus-he-said to-her Elkanah her-husband h#$y) hnql) hl rm)yw8a 8bHannah hnx8b 8cWhy you-weep? ykbt hml8c 8dAnd-why not you-eat? ylk)t )l hmlw8d 8eAnd-why it-is-resentful your-heart? Kbbl (ry hmlw8e 8fNot I better to-you than-ten sons? .Mynb hr#(m Kl bw+ ykn) )wlh8f Some explanation about this episode's distinctive temporal sequential of events demands special attention. -

Mayfair Travel for Information and to Register 856-735-0411 [email protected]

Israel Discovery 2018 With Pastor Mark Kirk JUNE 4 – 16N, 2018 Highlights “His foundation is in the holy mountains. The Lord loves the gates of Zion more than all the dwellings of Jacob. Glorious things are spoken of you, O city of God! Selah” Psalm 87 Join Pastor Mark Kirk on this increDible tour as he shares biblical insights at various archaeological sites and biblical locations. Experience the inspiring beauty of the lanD and expanD your knowleDge of GoD as the Bible is transformeD from imagination to reality. • RounDtrip Air to Tel Aviv • EscorteD motorcoach tour with expert Itinerary at-a-glance: driver & guide JUN 4 Depart Knoxville on your overnight flight to Tel Aviv • 10 nights loDging in upgraded hotels (2 Tel Aviv/ 3 Galilee/ 1 DeaD Sea/ 4 JUN 5 - 7 Tel Aviv: Rennaissance Hotel / 2 nights Jerusalem) Free day to explore Tel Aviv & Jaffa • Meals: Breakfast & Dinner daily JUN 7 - 10 Galilee Region: Gai Beach Resort / 3 nights • Premium inclusions (3 lunches, day at a DeaD Sea Resort, inDepenDent time, Caesarea, Mount Carmel, Tel MegiDDo, Capernaum, Sea of Galilee cruise, Nazareth Village, Mount Arbel, Golan Heights, MagDala, Ceasarea Philippi, Abraham Tent & Dinner) Tel Dan, Beit Shean, Kfar Blum, Baptism & more • All admission & site-seeing • PrepaiD tour gratuities JUN 10 - 11 Dead Sea: Isrotel Ghanim Hotel / 1 night • $50,000 emergency meDical insurance MasaDa, DeaD Sea, En GeDi overseas JUN 11 – 14 Jerusalem & Judean Desert: Leonardo Plaza / 4 nights: Mount of Olives, Palm Sunday RoaD, GarDen of Gethsemane, City of DaviD, Southern Steps, Western Wall & Rabbi’s Tunnels, Old City Jerusalem, Israel Museum, Holocaust Museum, Shiloh, Tel Jericho & much more JUN 13 Way of the Cross, Communion at GarDen Tomb anD Farewell Dinner JUN 14 Free day in Jerusalem JUN 15 Fly home with memories that last a lifetime Price: $4779 per person/double occupancy / Single Supplement $1098 *Registration due by June 30. -

Joshua 8:1-35 Calvary Baptist Church Sunday, January 14, 2018 Pastor Ben Marshall

Joshua: All In Passage: Joshua 8:1-35 Calvary Baptist Church Sunday, January 14, 2018 Pastor Ben Marshall Key Goals: (Know) We know that God desires us to be all in for Him. (Feel) We feel a compelling desire to go all in for God. (Do) We will go all in for God. Welcome Have you ever been in a conversation with someone, but you were slightly distracted? For whatever reason, you were not fully invested in the conversation—you had your phone out, or happened to be checking your email or Facebook status, or the TV was on next to you, or you were in a hurry, or you just didn’t really want to be part of the conversation. But then, all of a sudden, there is this awkward silence and you realize the person you were talking to is waiting on a response… Yeah, I’ve never been there either. Just kidding. It happens probably too often to me. It seems to take a lot for us to be all in for something. We have to actually want something, or want what it can give us. We tend to be all in for things like our favorite football team, favorite coffee shop, favorite brand of technology (obviously Apple is the best), and things like that. We become great evangelists and preachers for what we are passionate about. There’s something different when it comes to how we approach spiritual matters. We feel awkward talking about them, almost ashamed that we read the Bible and learned something or went to church and heard something that transformed our lives. -

“7 the Lord Appeared to Abram and Said, “To Your Offspring I Will Give This Land.” So He Built an Altar There to the Lord, Who Had Appeared to Him

Introduction Genesis 12:7-8—“7 The Lord appeared to Abram and said, “To your offspring I will give this land.” So he built an altar there to the Lord, who had appeared to him. 8 From there he went on toward the hills east of Bethel and pitched his tent, with Bethel on the west and Ai on the east. There he built an altar to the Lord and called on the name of the Lord.” Abram: Idol worshipper Ur of the Chaldees (S Iraq—ruins still there, ziggurat, photos on the Internet of the ruins of the ziggurat) Speculated—Abram from wealthy family…had means to travel with father and family…wealth from making & selling idols, the HS reached down to this profiteer…idol maker & idol worshipper …just as He reached down one day to me and to you …with the message of justification by faith …and just like Abram, we were called out from our slavery to sin and to the world’s values …and challenged to begin a new life …and travel to a new destination with the Lord our God. Hebrews 11:8—By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going …and we were called, too, when confronted by the gospel, to begin our own journey to that which is promised us by our Lord…eternal life in His presence. …James 2:23 tells us Abraham answered God’s call…and therefore was a friend of God. -

Tel Dan ‒ Biblical Dan

Tel Dan ‒ Biblical Dan An Archaeological and Biblical Study of the City of Dan from the Iron Age II to the Hellenistic Period Merja Alanne Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Theology, at the University of Helsinki in the Main Building, Auditorium XII on the 18th of March 2017, at 10 a.m. ISBN 978-951-51-3033-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-3034-1 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2017 “Tell el-Kadi” (Tel Dan) “Vettä, varjoja ja rehevää laidunta yllin kyllin ‒ mikä ihana levähdyspaikka! Täysin siemauksin olemme kaikki nauttineet kristallinkirkasta vettä lähteestä, joka on ’maailman suurimpia’, ja istumme teekannumme ympärillä mahtavan tammen juurella, jonne ei mikään auringon säde pääse kuumuutta tuomaan, sillä aikaa kuin hevosemme käyvät joen rannalla lihavaa ruohoa ahmimassa. Vaivumme niihin muistoihin, jotka kiertyvät levähdyspaikkamme ympäri.” ”Kävimme kumpua tarkastamassa ja huomasimme sen olevan mitä otollisimman kaivauksille. Se on soikeanmuotoinen, noin kilometrin pituinen ja 20 m korkuinen; peltona oleva pinta on hiukkasen kovera. … Tulimme ajatelleeksi sitä mahdollisuutta, että reunoja on kohottamassa maahan peittyneet kiinteät muinaisjäännökset, ehkä muinaiskaupungin muurit. Ei voi olla mitään epäilystä siitä, että kumpu kätkee poveensa muistomerkkejä vuosituhansia kestäneen historiansa varrelta.” ”Olimme kaikki yksimieliset siitä, että kiitollisempaa kaivauspaikkaa ei voine Palestiinassakaan toivoa. Rohkenin esittää sen ajatuksen, että tämä Pyhän maan pohjoisimmassa kolkassa oleva rauniokumpu -

Iitinerary Brochure

Israel 2.0 Visiting Biblical Sites Not seen on your first Israel tour June 3-13, 2020 “Walk about Zion, go all around it, count its towers, consider well its ramparts; go through its citadels, that you may tell the next generation that this is God, our God forever and ever. He will be our guide forever.” ~ Psalm 48:12-14 “BiblicalWish you could return to Israel and visitSites additional biblical sitesSeldom Seen!” you did not see on your first tour of the land? Now is your chance! Under the direction of two experienced Bible teachers, this life- changing tour will pay careful attention to the biblical relevance of the sites and artifacts of Israel that are usually missed on one’s first tour of the Holy Land. This strong biblical emphasis on the authority and accuracy of the Word of God will allow you to have “devotions with your feet” as the Scriptures turn from black and white to Technicolor! Highlights for this 11-day tour include: • You will be staying in strategically located, 4-star hotels. These hotels are some of Israel’s finest! On-site Bible teachers: • You will visit over 30 biblically significant sites, including such locations as Acco, Dr. Richard Blumenstock Beit She’an, Shiloh, Mt. Gerizim, Shechem, & Dr. David M. Hoffeditz Beersheba, Jerusalem, and Gezer. Most of these sites the average tourist never visits! With over 50 years of teaching experience and the opportunity of You will travel by four-wheel vehicles to leading hundreds of individuals on countless biblical tours, these • teachers will ensure that you visit Kirbet Quiyafa—the fortress where make the most of your time David met Saul prior to fighting Goliath and abroad. -

Matriarchs and Patriarchs Exploring the Spiritual World of Our Biblical Mothers and Fathers

Matriarchs and Patriarchs Exploring the Spiritual World of our Biblical Mothers and Fathers. Biblical heroes, saints and sinners – role models to reflect upon. Sarah, Abel Pann 2 Matriarchs and Patriarchs Exploring the Spiritual World of our Biblical Mothers and Fathers. Biblical heroes, saints and sinners: role models to reflect upon. Elizabeth Young “It is a Tree of Life to all who hold fast to It” (Prov. 3:18) Matriarchs and Patriarchs: Exploring the Spiritual World of our Biblical Mothers and Fathers © Elizabeth Young 2005, Rev. Ed. 2007. All Rights Reserved. Published by Etz Hayim Publishing, Hobart, Tasmania Email: [email protected] This Study Book is made available for biblical study groups, prayer, and meditation. Etz Hayim Publishing retains all publishing rights. No part may be reproduced without written permission from Etz Hayim. Cover illustration: And Sara heard it in the tent door… by Abel Pann (1883-1963) 4 INDEX Abraham: From Seeker to Hasid 7 Sarah: A Woman of Hope 17 Isaac: Our Life is Our Story 35 Rebecca: On being Attentive to God 47 Jacob: Pathways Toward Teshuvah 57 Leah & Rachel: Searching for Meaning 69 6 Louis Glansman Abraham—the Hasid a model of perfect love The Hasid—one who loves God with such a depth of his being so as to ‚arouse a desire within God to let flow the source of his own soul in such a way that cannot be comprehended by the human mind‛ (The Sefat Emet). 7 8 ABRAHAM – FROM SEEKER TO HASID Abraham - from Seeker to Hasid What motivates a seeker? Some considerations. -

Four Judean Bullae from the 2014 Season at Tel Lachish

Klingbeil Et Al. Four Judean Bullae from the 2014 Season at Tel Lachish Martin G. Klingbeil, Michael G. Hasel, Yosef Garfinkel, and Néstor H. Petruk The article presents four decorated epigraphic bullae unearthed in the Level III destruction at Lachish during the 2014 season, focusing on the epigraphic, iconographic, and historical aspects of the seal impressions. Keywords: Lachish; Iron Age IIB; West Semitic paleography; ancient Near Eastern icono- graphy; grazing doe; Eliakim; Hezekiah uring the second season of The Fourth Expedi- a series of rooms belonging to a large Iron Age build- tion to Lachish (June–July 2014),1 four deco- ing were excavated.2 The Iron Age building lies just to D rated epigraphic bullae, two of them impressed the north of the northeast corner of the outer courtyard’s by the same seal, were found in Area AA (Fig. 1) where supporting wall of the Palace-Fort excavated by the Brit- ish expedition led by James L. Starkey (Tufnell 1953) and 1 The Fourth Expedition to Lachish is co-sponsored by The In- the Tel Aviv University expedition led by David Ussish- stitute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the kin (2004). This specific location has significance based Institute of Archaeology, Southern Adventist University under the di- rection of Yosef Garfinkel, Michael G. Hasel, and Martin G. Klingbeil. on the excavations in and around the “Solar Shrine” by Consortium institutions include The Adventist Institute of Advanced Yohanan Aharoni (1975) in the 1960s. Studies (Philippines), Helderberg College (South Africa), Oakland The bullae were stored in a juglet found in a room University (USA), Universidad Adventista de Bolivia (Bolivia), Vir- (Square Oa26) located in the southwestern part of the ginia Commonwealth University (USA), and Seoul Jangsin University Iron Age building (Fig.