DAVID LEVY, a PROFESSOR in the University of Washington's School of Information, Believes He May Have Witnessed the First-Ever Interruption-By-E-Mail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Washington Special Collections

UNIVERSITY CHRONOLOGY 1850 to 1859 February 28, 1854 Governor Isaac Ingalls Stevens recommended to the first territorial legislature a memorial to Congress for the grant of two townships of land for the endowment for a university. (“That every youth, however limited his opportunities, find his place in the school, the college, the university, if God has given him the necessary gifts.” Governor Stevens) March 22, 1854 Memorial to Congress passed by the legislature. January 29, 1855 Legislature established two universities, one in Lewis County and one in Seattle. January 30, 1858 Legislature repealed act of 1855 and located one university at Cowlitz Farm Prairies, Lewis County, provided one hundred and sixty acres be locally donated for a campus. (The condition was never met.) 1860 to 1869 December 12, 1860 Legislature passed bill relocating the university at Seattle on condition ten acres be donated for a suitable campus. January 21, 1861 Legislative act was passed providing for the selection and location of endowment lands reserved for university purposes, and for the appointment of commissioners for the selection of a site for the territorial university. February 22, 1861 Commissioners first met. “Father” Daniel Bagley was chosen president of the board April 16, 1861 Arthur A. Denny, Edward Lander, and Charles C. Terry deeded the necessary ten acres for the campus. (This campus was occupied be the University until 1894.) May 21, 1861 Corner stone of first territorial University building was laid. “The finest educational structure in Pacific Northwest.” November 4, 1861 The University opened, with Asa Shinn Mercer as temporary head. Accommodations: one room and thirty students. -

Business Practice: Selection of Peer Institutions

Office of Budget and Planning Business Practice: Selection of Peer Institutions The office is frequently asked to prepare reports and statistics that compare U-M against “peer” institutions. Comparisons can include business practices, specific metrics, outcomes, or other measures. The Provost’s Office has requested consistency in the list of institutions included as peers in reporting. This business practice establishes the selection method for peers based on the purpose of the comparison. There are two primary options for peer comparison groups: • Benchmarking Peers – See Appendix A • AAU Peers – See Appendix B The “benchmarking peers” group is the default for all comparisons. However, there may be situations where a larger set of institutions is required for meaningful comparisons. For example, this can happen when comparing state appropriations across institutions. Using the benchmarking peer list in this situation would mean comparing only nine public institutions and the comparison of U-M to these nine might not provide the intended message. Additional examples for use of the “AAU peers” are listed later. Benchmarking Peers The benchmarking peer list is based on the list of top institutions identified during the development of the faculty recruitment, retention, and departure report for the Provost’s Office. Each summer, the deans are asked to report on senior faculty recruitment, retention, and departure activity for their unit, including which institutions hire our faculty (or attempt to) or are the source of faculty new to the University of Michigan. Compilation of this information produces a list of the “top” institutions for this faculty activity. The baseline benchmarking peer list was established in 2014-15. -

Hilary Wething

Hilary Wething [email protected] ● (203) 231-8396 School of Public Policy Pennsylvania State University Pond Laboratory 322, University Park, PA 16802 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION 2020 Ph.D., Public Policy and Management 2019 Graduate Certificate: Demographic Methods, Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology Daniel J. Evans School of Public Policy and Management, University of Washington 2011 Bachelor of Science in Business Administration, Economics Creighton University 2011 Bachelor of Science, Mathematics Creighton University ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor of Public Policy, Jackman-McCourtney Early Career Professor, School of Public Policy, Pennsylvania State University, 2020- Faculty Associate, Population Research Institute, Penn State University, 2020- RESEARCH SUPPORT 2020-21 COVID Emergency Grant, PSU Population Research Institute 2019-20 Washington State Labor Research Grant, Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies 2018-19 Fellow, UW Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology 2018-19 Doctoral Grantee, Washington Center for Equitable Growth 2014-15 Blalock Fellowship Award UW, Center for Statistics and Social Sciences PUBLICATIONS Hill, H.D., Romich, J., Mattingly, M.J., Shamsuddin, S. & Wething, H. (2017). An Introduction to Household Economic Instability and Social Policy. Social Service Review, 91(3), 371-389. WORKING PAPERS * indicates researcher was a -

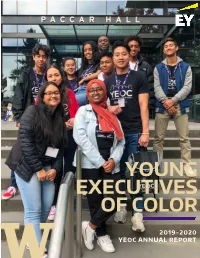

Young Executives of Color

YOUNG EXECUTIVES OF COLOR 2019-2020 YEOC ANNUAL REPORT PROGRAM OVERVIEW ETHNICITY TOTAL # TOTAL % MALE FEMALE African-American 84 44% 30 54 The Young Executives of Color (YEOC) program is a nine-month college pipeline program hosted by the University of Washington Michael G. Hispanic/Latinx 59 31% 26 33 Foster School of Business. Focused on engaging and assisting high Asian-American/Southeast Asian 36 19% 9 27 school students from historically underrepresented minority Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander 2 1% 2 communities, YEOC began in 2006 with 36 students representing Alaska Native/American-Indian 3 2% 2 1 17 high schools. After 13 years, YEOC has grown to 190 participants Multiracial 6 3% 5 1 representing 75 high schools across Washington state. One Saturday per month, these Young Executives travel from across GRADE TOTAL # TOTAL % MALE FEMALE Washington state to attend sessions on the UW campus. Due to Senior 113 59% 43 70 generous sponsorship from EY, tuition for the YEOC program is FREE, Junior 54 29% 19 35 with the only cost to students being their transportation to UW Seattle. Sophomore 23 12% 13 10 Over the course of the year, YEOC participants are exposed to a TOTAL comprehensive curriculum including: college preparation, professional 190 75 115 PARTICIPANTS development, leadership activities, and lectures rooted in business disciplines. Each Young Executive is paired with a Foster School of FIRST GENERATION 76% 48 96 Business undergraduate student Mentor who helps them navigate the COLLEGE STUDENTS* 144 program, develop tools for academic and personal success, and CUMULATIVE GPA prepare for college applications and scholarships. -

Katherine Ball

Katherine Ball School for the Future of Innovation in Society Arizona State University [email protected] Linkedin: katherineball1 Research Interests Public engagement in policy; Coastal communities and marine development; community learning Education PHD IN HUMAN AND SOCIAL DEMINSIONS OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY | ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY | IN PROGRESS MASTERS IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POLICY | ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY | 2019 Applied Project: Participatory Game Design for Environmental Action Advisor: Kirk Jalbert BACHELORS OF SCIENCE OCEANOGRAPHY | UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, SEATTLE | 2016 Senior thesis: Light Refraction for In-Situ Micro-Plastic Sampling: m-PARR as a Low-Cost Sampling Device Advisor: Miles Logsdon Related coursework: Pacific Tourism, International Organizations, Ocean Technology series, Intro to ArcGIS ASSOCIATES IN ART & SCIENCE | OCEAN RESEARCH COLLEGE ACADEMY, EVERETT COMMUNITY COLLEGE | 2014 Emphasis area: Oceanography Research Experience GRADUATE RESEARCH ASSISTANT | ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY | AUGUST 2018-CURRENT Researched how concerned citizen groups utilize data and use it to make change on environmental issues such as fracking and pipelines Studied changes in public engagement requirements in the National Environmental Policy Act and the impact on emerging concerned citizen groups RESOURCE EDUCATION INTERN | NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ALASKA | SUMMER 2018 Researched and developed a college-level lesson on the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act BENTHIC ACOUSTIC MAPPING AND SURVEY PROGRAM | UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON -

Faculty and Staff 1

Faculty and Staff 1 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. BS 1981 George Washington FACULTY AND STAFF University. Scott Fletcher: dean; professor of education. PhD 1997 University of Faculty Colorado-Boulder. MA 1985 University of Wisconsin-Madison. BA 1981 Mary Andrus: art therapy program director; assistant professor of art Ripon College. therapy. DAT 2017, Mount Mary University. MAAT 2000, The School of the Mollie Galloway: chair of the department of educational leadership; Art Institute of Chicago. doctor of education in leadership program director; associate professor Joslyn Armstrong: assistant professor of marriage, couple, and family of educational leadership. PhD 2003 Stanford University. BA 1998 Johns therapy. PhD 2019, The Florida State University. MS 2015, Texas Tech Hopkins University. University. BS 2013, University of Florida. Linda Griffin: elementary program director; assistant professor of Megan Barret: professional license program director; assistant professor education. EdD 2006 Northern Arizona University. MA 1994 University of of educational administration. MEd 2003, Portland State University. BA Arizona. BA 1981 University of California. 2000, Reed College. Heather Hadraba: school counseling program director; assistant Kristine Bella: clinical coordinator and instructor in art therapy. MA 1997, professor of school counseling. PhD 2011 Oregon State University. MS Marylhurst College. BA 1995, University of Wyoming. 2003 Oregon State University. BS 2001 Oregon State University. Janet Bixby: associate dean; associate professor of education. PhD 2001, Justin Henderson: community counseling center director; assistant University of Wisconsin at Madison. MEd 1989, Harvard University. BA professor of professional mental health counseling. PhD 2012 University 1986, Harvard University/Radcliffe College. of Nebraska-Lincoln. MS 2007, BA 2005 University of Wyoming. -

Vol. 13, No. 2 (PDF)

FOREST AND WILDLIFE ECOLOGY NEWS A Newsletter for Dept. of Forest and Wildlife Ecology Staff, Students and Alumni Vol. 13, No. 2 October 2010 tain and improve programs that provide Chief of Operations for Milwaukee County News from excellent training and a continuing stream Department of Parks, Recreation, and the Chair of people, as capable as our alumni, to Culture. In addition, Guy will receive the carry on into the future the important work National Recreation Park Association’s of management and conservation of natu- Young Professional of the Year Award at its t is so gratifying to read another issue ral resources. conference in October in the Twin Cities. Iof Forest and Wildlife Ecology News. Email: [email protected] The many activities and impacts of our alumni, and current faculty members and Erin Kreutz (B.S. Forest Science 2001) their trainees (including undergraduate, plans to wrap up her Master’s degree in Natural and Cultural Resource Management graduate, postdoctoral) at the state, Alumni Update at Central Washington University this win- national, and international level will ter. Her thesis focuses on the feasibility of inspire our dozen newest graduate stu- Washington State DNR selling carbon cred- dents, who are introduced in this issue. its during a down timber market to support You will be proud to learn of a late-break- The 2000s the State Trusts (primarily K-12 education). ing announcement that underscores these Congratulations to Margaret (Maggie) Erin also works for Natural Resources achievements. The National Research Milligan (formerly Margaret Grosenick) Conservation Service in Ellensburg, WA. Council just released its "Data-Based (B.S. -

1 University of Washington (Seattle) General Information Q1. Full Name

Waseda University Center for International Education Global Leadership Fellows Program Inquiry Sheet 2021-2022 University of Washington (Seattle) General Information Q1. Full name of your institution in English The University of Washington (Seattle) Q2. Brief introduction of your institution (up to 200 words) and the URL The University of Washington is located in Seattle, on a beautifully green campus about 10 minutes away from downtown. The UW has earned an international reputation for its research and graduate programs in a host of disciplines, as well as its professional schools of Law, Medicine, and Nursing, among others. It is a leader in a variety of fields, and was one of the first universities in the US to foster Asian studies, over a hundred years ago. Research is of great benefit to the broader community, and undergraduates benefit by learning from professors who are at the forefront of generating new knowledge. UW's graduate programs are among the most highly rated in the nation. Facts & Figures Founded in: 1861 Undergraduate students: 31,525 (Seattle campus) Graduate students: 14,345 (Seattle campus) Full-time faculty: 3859 Part-time faculty: 1308 Library holding: over 6 million e-journal articles and 7 million print volumes http://www.washington.edu/studyabroad/ (The link to Study Abroad) http://www.washington.edu (General website) The Honors Program, a division of Undergraduate Academic Affairs, is a high-profile unit that attracts promising students from Washington State and around the globe. As an innovative laboratory for interdisciplinary inquiry, students reach across the university, sharing their intellect and enthusiastic engagement with local, national, and international communities. -

Alumni Activities School of Medicine

Yale University School of Medicine Class of 2012 Graduates in Residency Programs 101 students were awarded a Doctor of Medicine Degree from Yale School of Medicine in 2012. 99 students matched into residency programs in locations across the U.S. and Canada. 2 Students choose alternative careers. Specialty: City State Anesthesiology Mount Sinai Hospital New York NY New York Presbyterian Hospital - Columbia New York NY University of California - San Francisco San Francisco CA University of Utah Affiliated Hospitals Salt Lake City UT Yale-New Haven Hospital New Haven CT Dermatology Cleveland Clinic Foundation Cleveland OH Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia PA McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University Chicago IL New York University School of Medicine New York NY Rhode Island Hospital / Brown University Providence RI University of California - San Diego San Diego CA University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Pittsburgh PA Vanderbilt University Medical Center Nashville TN Diagnostic Radiology Alleghany General Hospital-Western Pennsylvania Hospita Pittsburgh PA Brigham and Women's Hospital Boston MA Emory University Atlanta GA Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia PA University of Washington Affiliated Hospitals Seattle WA Emergency Medicine Mount Sinai Hospital New York NY Oregon Health & Science University Portland OR University of California - San Francisco San Francisco CA University of Chicago Medical Center Chicago IL University of Southern California Los Angeles CA Yale-New Haven Hospital New -

Faculty & Administration At

B.A., State University of New York; M.A., California Faculty & Administration State University at LCC Paz Clearwater (2016), Director of Student Programs B.A., Washington State University Administration Byron Ford (2018), Director of Advising and Testing B.A. and M.E., Western Washington University President Desiree Gamble (2007), Director of Finance A.A., Lower Columbia College; B.A., Washington State Christopher C. Bailey (2011) University B.A., Western Washington University; J.D., University of Washington School of Law Marisa Geier (2004), Director of Financial Aid A.A., Lower Columbia College; B.S., Western Baptist Vice Presidents College; M.P.A., Walden University Kristen Finnel (2019), Vice President of Instruction Sarah Griffith (2010), Director of eLearning A.A.S, Tidewater Community College; B.S., Norfolk B.A., Abilene Christian University State University; M.Ed., Concordia University; Ed.D., Edgewood College Richard Hamilton (2001), Director of Campus Services, Facilities and Capital Projects Wendy Hall (2003), Vice President of Effectiveness & A.S., City University; A.A., Lower Columbia College; College Relations B.A., Washington State University B.A., Whitman College; M.P.A., University of Washington Mindy Leasure (2007), Director of Head Start/ECEAP/ EHS Sue Orchard (2016), Vice President of Student B.A., University of Washington; MSMOL., Warner Services Pacific College B.A. and M.A., Eastern Washington University; Psy.D., Pacific University School of Professional Psychology Alyssa Milano-Hightower (2020), Director of Enterprise -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Kenneth Martin Rice, Ph.D. 1. Date September 29, 2020 2. Biographical Information Kenneth Martin Rice University of Washington Biostatistics Department Box 357232, HSB F-649 Seattle, WA 98195-7232, U.S.A. http://faculty.washington.edu/kenrice Phone: 206 616 6174 Fax: 206 543 3286 Email: [email protected] 3. Education Churchill College, Cambridge University. B.A. Hons, Mathematics, 1st class, 1995 Churchill College, Cambridge University. Diploma in Mathematical Statistics, with distinction, 1998 ("Analysis of phenotypic variation in Von Hippel Lindau Disease", supervised by D Easton) Churchill College, Cambridge University. Ph.D, Biostatistics, 2001 ("Models for misclassification of covariables in epidemiology", supervised by D Spiegelhalter, PME Altham) 4. Licensure: Not applicable 5. Professional Positions Research Associate, MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, 2001-2004 Assistant Professor, University of Washington, Seattle WA, 2004-2010 Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle WA, 2010-2018 Professor, University of Washington, Seattle WA, 2018- 6. Honors, Awards, Scholarships Scholarship award, Churchill College, Cambridge University, 1995 Cambridge University Wishart Prize for Statistics, 1998 Cambridge University Smith-Knight and Rayleigh-Knight Prize for Applied Mathematics Essay, “Misclassification of Exposure in Case-Control Studies”, 2000 European Young Researcher Award to attend International Workshop on Statistics with Deficient Data, Munich, 2000 Kenneth Rice 2 Curriculum -

The University of Washington Is a Very Selective School

A Perspective from the University of Washington by Jenni Cole, Admissions, School of Music It’s no secret that the University of Washington is a very selective college. For Fall 2008, we received almost 20,000 freshman applications and only offered admission to slightly more than 12,000 of these students. That made for a 61 percent acceptance rate – competitive by any standard! What, then, can a prospective student do to stand out in this sea of applicants? Is participation in music enough to separate music students from the crowd? I met with Paul Seegert, Associate Director of Operations for Undergraduate Admissions, to seek answers to these questions. What does the UW look for in freshman applicants? The UW uses a holistic approach in the admissions process. This means that every student’s application is read carefully and thoroughly by at least two people, and every part of a student’s application is taken into consideration. In this process, the first thing we look at is academics. The UW’s curriculum is rigorous, and Admissions screens every applicant to make sure that he or she will be academically successful. To do this, we consider the courses a student has taken, the grades he or she earned and SAT/ACT scores. Admissions also considers other factors, like the writing sample and extracurricular activities. Will participation in music help me get into the UW? Involvement in extracurricular activities is a must on any college application, but is one kind of activity better than another? Not really, according to Mr. Seegert. Rather than being picky about the kind of extracurricular involvement in which students are engaged, the UW wants to see how they were involved in that activity.