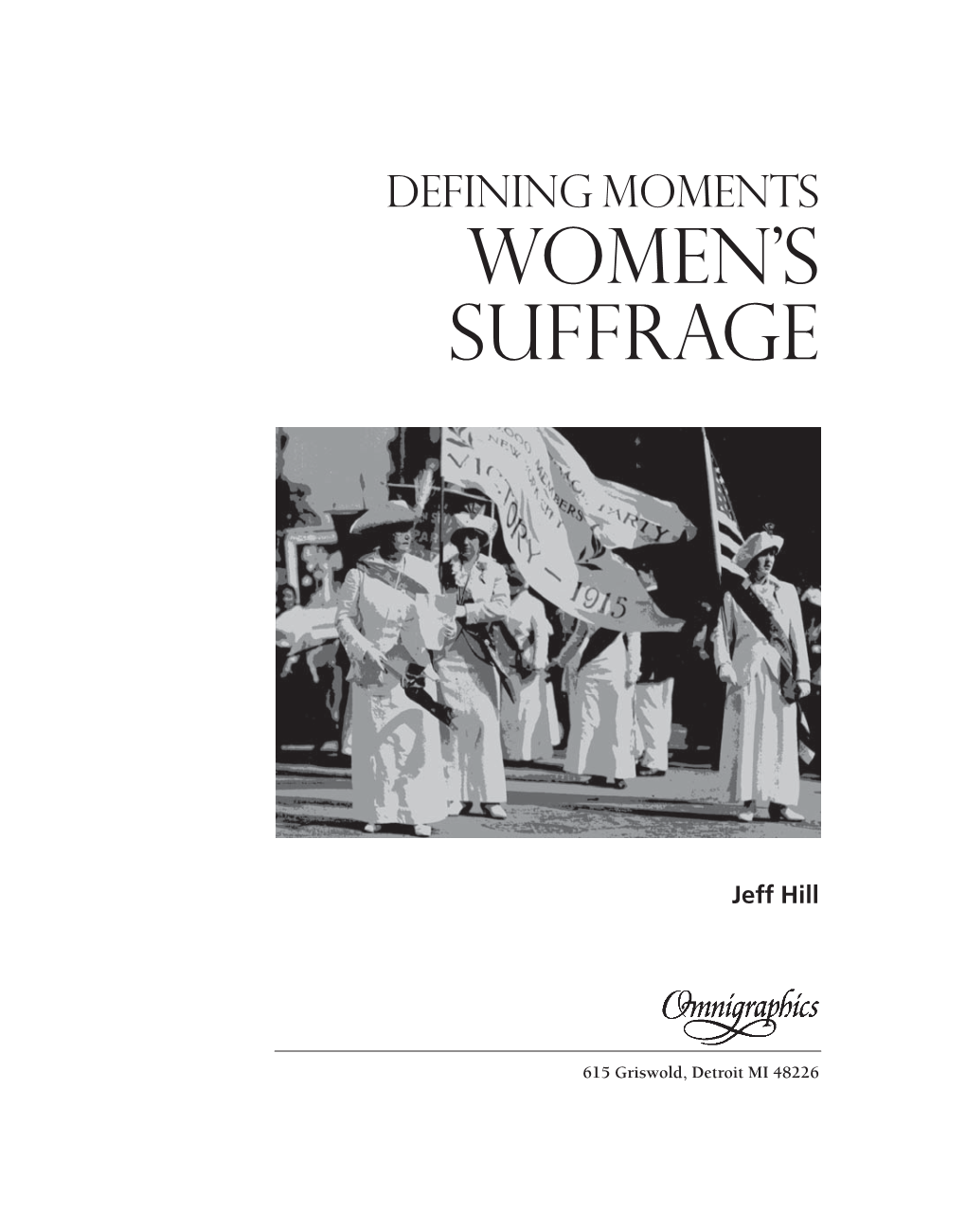

Suffrage MB 8/17/05 9:04 AM Page 65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Mothers and the Postponement of Women's

SUK_FINAL PROOF_REDLINE.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 3/13/2021 4:13 AM WORKING MOTHERS AND THE POSTPONEMENT OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS FROM THE NINETEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT JULIE C. SUK* The Nineteenth Amendment’s ratification in 1920 spawned new initiatives to advance the status of women, including the proposal of another constitutional amendment that would guarantee women equality in all legal rights, beyond the right to vote. Both the Nineteenth Amendment and the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) grew out of the long quest to enshrine women’s equal status under the law as citizens, which began in the nineteenth century. Nearly a century later, the ERA remains unfinished business with an uncertain future. Suffragists advanced different visions and strategies for women’s empowerment after they got the constitutional right to vote. They divided over the ERA. Their disagreements, this Essay argues, productively postponed the ERA, and reshaped its meaning over time to be more responsive to the challenges women faced in exercising economic and political power because they were mothers. An understanding of how and why *Professor of Sociology, Political Science, and Liberal Studies, The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and Florence Rogatz Visiting Professor of Law (fall 2020) and Senior Research Scholar, Yale Law School. Huge thanks to Saul Cornell, Deborah Dinner, Vicki Jackson, Michael Klarman, Jill Lepore, Suzette Malveaux, Jane Manners, Sara McDougall, Paula Monopoli, Jed Shugerman, Reva Siegel, and Kirsten Swinth. Their comments and reactions to earlier iterations of this project conjured this Essay into existence. This Essay began as a presentation of disconnected chunks of research for my book, WE THE WOMEN: THE UNSTOPPABLE MOTHERS OF THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT (2020) , but the conversations generated by law school audiences nudged me to write a separate essay to explore more thoroughly how the story of suffragists’ ERA dispute after the Nineteenth Amendment affects the future of constitutional lawmaking. -

Meet the Suffragists (Pdf)

Meet The Suffragists A Presentation by the 2018-2020 GFWC-SC Ad Hoc Committee to Celebrate the Centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment Meet the Suffragists Susan B. Anthony Champion of temperance, abolition, the rights of labor, and equal pay for equal work, Susan Brownell Anthony became one of the most visible leaders of the women’s suffrage movement. Born on February 15, 1820 in Adams, Massachusetts, Susan was inspired by the Quaker belief that everyone was equal under God. That idea guided her throughout her life. She had seven brothers and sisters, many of whom became activists for justice and emancipation of slaves. In 1851, Anthony met Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The two women became good friends and worked together for over 50 years fighting for women’s rights. They traveled the country and Anthony gave speeches demanding that women be given the right to vote. In 1872, Anthony was arrested for voting. She was tried and fined $100 for her crime. This made many people angry and brought national attention to the suffrage movement. In 1876, she led a protest at the 1876 Centennial of our nation’s independence. She gave a speech—“Declaration of Rights”— written by Stanton and another suffragist, Matilda Joslyn Gage. Anthony died in 1906, 14 years before women were given the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920. Submitted by Janet Watkins Carrie Chapman Carrie Chapman Catt was born January 9, 1859 in Ripon, Wisconsin. She attended Iowa State University. She was married to Leo Chapman (1885-1886); George Catt (1890-1905); partner Mary Garret Hay. -

19Th Amendment Conference | CLE Materials

The 19th Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Center for Constitutional Law at The University of Akron School of Law Friday, Sept. 20, 2019 CONTINUING EDUCATION MATERIALS More information about the Center for Con Law at Akron available on the Center website, https://www.uakron.edu/law/ccl/ and on Twitter @conlawcenter 001 Table of Contents Page Conference Program Schedule 3 Awakening and Advocacy for Women’s Suffrage Tracy Thomas, More Than the Vote: The 19th Amendment as Proxy for Gender Equality 5 Richard H. Chused, The Temperance Movement’s Impact on Adoption of Women’s Suffrage 28 Nicole B. Godfrey, Suffragist Prisoners and the Importance of Protecting Prisoner Protests 53 Amending the Constitution Ann D. Gordon, Many Pathways to Suffrage, Other Than the 19th Amendment 74 Paula A. Monopoli, The Legal and Constitutional Development of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Decade Following Ratification 87 Keynote: Ellen Carol DuBois, The Afterstory of the Nineteth Amendment, Outline 96 Extensions and Applications of the Nineteenth Amendment Cornelia Weiss The 19th Amendment and the U.S. “Women’s Emancipation” Policy in Post-World War II Occupied Japan: Going Beyond Suffrage 97 Constitutional Meaning of the Nineteenth Amendment Jill Elaine Hasday, Fights for Rights: How Forgetting and Denying Women’s Struggles for Equality Perpetuates Inequality 131 Michael Gentithes, Felony Disenfranchisement & the Nineteenth Amendment 196 Mae C. Quinn, Caridad Dominguez, Chelsea Omega, Abrafi Osei-Kofi & Carlye Owens, Youth Suffrage in the United States: Modern Movement Intersections, Connections, and the Constitution 205 002 THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AT AKRON th The 19 Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Friday, September 20, 2019 (8am to 5pm) The University of Akron School of Law (Brennan Courtroom 180) The focus of the 2019 conference is the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. -

When Rosa Parks Died in 2005, She Lay in Honor in the Rotunda of the Capitol, the First Woman and Only the Second Person of Color to Receive That Honor

>> When Rosa Parks died in 2005, she lay in honor in the Rotunda of the Capitol, the first woman and only the second person of color to receive that honor. When Congress commissioned a statue of her, it became the first full-length statue of an African American in the Capitol. It was unveiled on what would have been her 100th birthday. I sat down with some of my colleagues to talk about their personal memories of these events at the Capitol and the stories that they like to tell about Rosa Parks to visitors on tour. [ Music ] You're listening to "Shaping History: Women in Capitol Art" produced by the Capitol Visitor Center. Our mission is to inform, involve, and inspire every visitor to the United States Capitol. I'm your host, Janet Clemens. [ Music ] I'm here with my colleagues, and fellow visitor guides, Douglas Ike, Ronn Jackson, and Adriane Norman. Everyone, welcome to the podcast. >> Thank you. >> Thank you. >> Great to be here. >> Nice to be here. >> There are four of us around this table. I did some quick math, and this is representing 76 years of combined touring experience at the Capitol. And I'm the newbie here with only a decade [laughter]. Before we begin, I'm going to give my colleagues the opportunity to introduce themselves. >> I'm Douglas Ike, visitor guide here at the U.S. Capitol Building. I am approaching 17 years as a tour guide here at the Capitol. >> Adriane Norman, visitor guide, October 11, 1988, 32 years. >> Ronn Jackson, approaching 18 years. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: the President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Behn, Beth, "Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The rP esident and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 511. https://doi.org/10.7275/e43w-h021 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of History © Copyright by Beth A. Behn 2012 All Rights Reserved WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Joyce Avrech Berkman, Chair _________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Member _________________________________ David Glassberg, Member _________________________________ Gerald McFarland, Member ________________________________________ Joye Bowman, Department Head Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have completed this dissertation without the generous support of a number of people. It is a privilege to finally be able to express my gratitude to many of them. -

The National Woman's Party and the Occoquan Workhouse Lesson

The National Woman’s Party and the Occoquan Workhouse Lesson Written and arranged by Erica W. Benson M.A. North American History, M.A. Secondary Education: Teaching, B.A. History, B.S. Journalism Essential Historical Question - Was the justice system fair and Constitutional in its treatment of the National Woman’s Party picketers? - What role did the Occoquan Workhouse play in the women’s suffrage movement? Recommended Time Frame: - At least one 45/50-minute class period, if you plan it for a longer class period you have the opportunity to show clips of the HBO film Iron Jawed Angels. - Question 13 can be assigned for homework and submitted online or written by hand. Pre-requisites: It is helpful if students have studied WWI so they can understand the context of the final push for suffrage and the messaging and strategy used by the NWP to pressure President Wilson. Materials: ● Primary Source Document sets for pair groupings (upload online if students have computers or print) ● Phased guided questions/position questions – one copy for each student ● A projector to play film clips (you can typically find Iron Jawed Angels for free online, or you can purchase the DVD – you won’t regret it!) Procedures: Step-by-step plan of instruction: 1. Open the class with a 3-minute quick write: “What free speech rights do Americans have? Is it ever limited, if so, when? ” After a few minutes post/reveal the 1st Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” Students will have a variety of responses and examples to draw from; ask students to share what they wrote with a neighboring student. -

Iowa's Role in the Suffrage Movement

Lesson #5 Commemorating the Centennial Of the 19th Amendment Designed for Grades 9-12 6 Lesson Unit/Each Lesson 2 Days Based on Iowa Social Studies Standards Iowa’s Role in the Suffrage Movement Unit Question: What is the 19th Amendment, and how has it influenced the United States? Supporting Question: How was Iowa involved in the promotion of and passage of the 19th Amendment? Lesson Overview The lesson will highlight suffrage leaders with Iowa ties and events in the state leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment. Lesson Objectives and Targets Students will… 1. take note of key events in Iowa’s path to achieve women’s enfranchisement. 2. read provided biographical entries on selected Iowa suffrage leaders. 3. read and review the University of Iowa Library Archives selections on suffrage, selections from the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics website, and the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame coverage about Iowa suffragists and contemporary Iowa women leaders.. Useful Terms and Background ● Iowa Organizations - Iowa Woman Suffrage Association (IWSA), Iowa Equal Suffrage Association (IESA) along with several local and state clubs of support ● National suffrage leaders with Iowa roots - Amelia Jenks Bloomer & Carrie Chapman Catt ● Noted Iowa suffragists included in the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame ● Suffrage activities throughout the state ● Early state attempts for amendments along with Iowa ratification of the 19th Amendment Lesson Procedure Day 1 Teacher Notes for Day 1 1. Point out that lesson materials have been selected from three unique Iowa sources: the University of Iowa Library Archives and the websites for Iowa State University’s Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics and the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame. -

5Th Grade Learning Guide ELA

5th Grade Learning Guide ELA Note to Parents: The learning guides can be translated using your phone! How to Translate the Learning Guides: 1. Download the Google Translate app 2. Tap "Camera" 3. Point your camera at the text you want to translate 4. Tap "Scan" 5. Tap “Select all” ________________________________________________________________________________________ How to Use This Learning Guide: There are 3 core parts to this learning guide. First: Parents/students are provided with the text/story that can be read. ● In grades levels K-2, the text is found at the end of the learning guide. ● In grades levels 3 -5, the texts are found at the start of each lesson. Next: Parents/students are provided with an overview of what will be learned and are provided supports to help with learning (vocabulary, questions, videos, websites). ● Vocabulary words in bold are the most important for understanding the text. Finally: Parents/students are provided with the activities that can be completed using the text/story. ● Directions for the activities are provided and the directions for the choice board activities tell students how many tasks to complete. ● For choice boards, students should pick activities that interest them and that allow them to demonstrate what they have learned from the text/story. ● The Answer Key and Modifications Page are at the end of the Learning Guide to support your child. ● The Modifications Page includes Language Development resources for Newcomers. 1 Grade: 5 Subject: English Language Arts Topic: African American Suffragists by Margaret Gushue and Learning to Read by Francis Ellen Watkins Harper Access the text HERE and HERE or Embedded HERE What Your Student is Learning: Your student will read paired texts African American Suffragists and Learning to Read. -

How the Women's Rights Movement Began

How The Women’s Rights Movement Began As it was written in 1787, the Constitution said little about black slaves. It said nothing about women. At the time of the Constitutional Convention, women were treated like children. Adult females were barred from most occupations and professions. They could not make binding contracts or sue people in court. Even though women could be tried for crimes, they were excluded from juries. In most cases, any money or land a woman possessed became the property of her husband once she married. A married woman gave up all individual status; she kept no legal right to her own earnings or even personal belongings such as clothing or jewelry. Most states did not allow single women or widows sole control over their own property, either. Most men simply believed women were not capable of handling business affairs. When the Constitution was written, women could vote only in New Jersey, but by 1807, even this state had banned suffrage (the right of women to vote in governmental elections). The main argument against women voting assumed they would be too easily influenced by their fathers, brothers and husbands. According to this view, if women voted, a married man would control twice the voting power of a single male. From Abolition to Women’s Rights The lack of political clout did not discourage women from becoming deeply involved in public affairs. Lucretia Mott was raised by a MassachusettsLucretia Mott Quaker Wikimedia father Commons) who believed in equal education for girls. She became a teacher and married another Quaker teacher. -

Women's History Month, 2007

Proc. 8109 Title 3—The President We are grateful for the tireless work of the volunteers and staff of the American Red Cross. During this month, we pay tribute to this remarkable organization and all those who have answered the call to serve a cause greater than self and offered support and healing in times of need. NOW, THEREFORE, I, GEORGE W. BUSH, President of the United States of America and Honorary Chairman of the American Red Cross, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim March 2007 as American Red Cross Month. I commend the good work of the American Red Cross, and I encourage all Americans to help make our world a better place by volunteering their time, energy, and talents for others. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this twenty-seventh day of February, in the year of our Lord two thousand seven, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and thirty- first. GEORGE W. BUSH Proclamation 8109 of February 27, 2007 Women’s History Month, 2007 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation Throughout our history, the vision and determination of women have strengthened and transformed America. As we celebrate Women’s History Month, we recognize the vital contributions women have made to our country. The strong leadership of extraordinary women has altered our Nation’s his- tory. Sojourner Truth, Alice Stone Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe opened doors for future generations of women by advancing the cause of women’s voting rights and helping make America a more equitable place. -

The Women's Suffrage Movement

Name _________________________________________ Date __________________ The Women’s Suffrage Movement Part 1 The Women’s Suffrage Movement began with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. The idea for the Convention came from two women: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Both were concerned about women’s issues of the time, specifically the fact that women did not have the right to vote. Stanton felt that this was unfair. She insisted that women needed the power to make laws, in order to secure other rights that were important to women. The Convention was designed around a document that Stanton wrote, called the “Declaration of Sentiments”. Using the Declaration of Independence as her guide, she listed eighteen usurpations, or misuses of power, on the part of men, against women. Stanton also wrote eleven resolutions, or opinions, put forth to be voted on by the attendees of the Convention. About three hundred people came to the Convention, including forty men. All of the resolutions were eventually passed, including the 9th one, which called for women’s suffrage, or the right for women to vote. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott signed the Seneca Falls Declaration and started the Suffrage Movement that would last until 1920, when women were finally granted the right to vote by the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. 1. What event triggered the Women’s Suffrage Movement? ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ 2. Who were the two women