Called to Common Mission: a Lutheran Proposal?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Love and Serve the Lord

TO LOVE AND SERVE THE LORD Diakonia in the Life of the Church The Jerusalem Report of the Anglican–Lutheran International Commission (ALIC III) Published by the Lutheran World Federation 150, route de Ferney P.O. Box 2100 CH-1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland © Copyright 2012, jointly by The Lutheran World Federation and the Secretary General of the Anglican Communion. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permis- sion in writing from the copyright holders, or as expressly permitted by law, or under the terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. Printed in France by GPS Publishing TO LOVE AND SERVE THE LORD Diakonia in the Life of the Church The Jerusalem Report of the Anglican–Lutheran International Commission (ALIC III) To Love and Serve the Lord Diakonia in the Life of the Church The Jerusalem Report of the Anglican–Lutheran International Commission (ALIC III) Editorial assistance: Cover: LWF/DTPW staff LWF/OCS staff Anglican Communion Office staff Photo: ACNS/ Neil Vigers Design and Layout: Photo research and design: LWF/OCS staff LWF/DTPW staff Anglican Communion Office staff ISBN 978-2-940459-24-7 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................. 4 I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 6 II. Diakonia -

Apostolic Succession in the Porvoo Common Statement Unity Through a Deeper Sense of Apostolicity

Apostolic Succession in the Porvoo Common Statement Unity through a deeper sense of apostolicity Erik Eckerdal Uppsala University Thesis 2017-08-01 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Ihre-salen, Engelska parken, Uppsala, Friday, 22 September 2017 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Theology). The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Susan K Wood (Marquette University). Abstract Eckerdal, E. 2017. Apostolic Succession in the Porvoo Common Statement. Unity through a deeper sense of apostolicity. 512 pp. Uppsala: Department of Theology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2829-6. A number of ecumenical dialogues have identified apostolic succession as one of the most crucial issues on which the churches need to find a joint understanding in order to achieve the unity of the Church. When the Porvoo Common Statement (PCS) was published in 1993, it was regarded by some as an ecumenical breakthrough, because it claimed to have established visible and corporate unity between the Lutheran and Anglican churches of the Nordic-Baltic-British-Irish region through a joint understanding of ecclesiology and apostolic succession. The consensus has been achieved, according to the PCS, through a ‘deeper understanding’ that embraces the churches’ earlier diverse interpretations. In the international debate about the PCS, the claim of a ‘deeper understanding’ as a solution to earlier contradictory interpretations has been both praised and criticised, and has been seen as both possible and impossible. This thesis investigates how and why the PCS has been interpreted differently in various contexts, and discerns the arguments used for or against the ecclesiology presented in the PCS. -

The Lutheran Episcopal Coordinating Committee Met at the Lutheran Center in Chicago on October 15-17, 2019

Almost Two Decades of Life Together: How Do We Encourage Next Steps? Lutheran-Episcopal Coordinating Committee (LECC) October 15-17, 2019 Lutheran Center, Chicago, Illinois The Lutheran Episcopal Coordinating Committee met at the Lutheran Center in Chicago on October 15-17, 2019. This committee is charged with encouraging and assisting efforts in The Episcopal Church (TEC) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) as they live into their relationship of full communion provided for in “Called to Common Mission” (CCM). The meeting recognized that as we stand on the verge of 20 years of full communion experience, this relationship has grown and matured in many ways; At the same time, rapid change has come both to our church bodies and our religious landscape; thus many factors invite new ways of moving forward. The committee welcomed new members from TEC: The Rev. Jane Johnson and the Rev. T. Stewart Lucas. It conveyed its thanks for the work of its former member the Rev. Canon Dr. David Perry, who sent a message of counsel and hope for further direction. Other TEC members are the Rt. Rev. Douglas Sparks, Co-Chair, and the Rev. Nancy McGrath Green. Present on the Lutheran side were co-chair Bishop Donald Kreiss and Dr. Mitzi Budde. ELCA members the Rev. Canon Natalie Hall and the Rev. Kari Jo Verhulst and Episcopal member the Rev. Nils Chittenden were unable to attend. Staff were the Rev. Margaret Rose and Richard Mammana (TEC) and Kristen Opalinski and Kathryn Johnson (ELCA). Common prayers for the meeting were drawn again from the Episcopal resource, Daily Prayer for All Seasons, and from the new ELCA Hear My Prayer: A Prison Prayer Book, produced by an ecumenical writing team headed by LECC member Mitzi Budde and commended by both Presiding Bishops. -

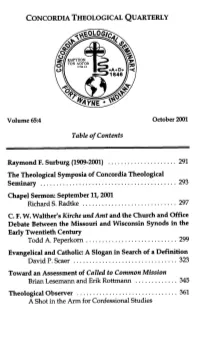

Toward an Assessment of Called to Common Mission Brian Lesemann and Erik Rottrnann

Volume 65:4 October 2001 Table of Contents Raymond F. Surburg (1909-2001) . 291 The Theological Symposia of Concordia Theological Seminary . 293 Chapel Sermon: September 11,2001 Richard S. Radtke . 297 C. F. W. Walther's Kirche und Amt and the Church and Office Debate Between the Missouri and Wisconsin Synods in the Early Twentieth Century Todd A. Peperkorn . 299 Evangelical and Catholic: A Slogan in Search of a Definition David P. Scaer . , . 323 Toward an Assessment of Called to Common Mission Brian Lesemann and Erik Rottrnann . 345 Theological Observer . 361 A Shot in the Arm for Confessional Studies Book Reviews ......................................363 Damin's Black Box-the Biochemical Challenge to Evolution. By Michael J. Behe. .............. James D. Heiser Those Terrible Middle Ages! Debunking the Myths. By R6gine Pernoud. Translated by Anne Englund Nash. ..............................James G. Kroemer Discovering the Plain Truth: How the Worldwide Church oj God Encountered the Gospel of Grace. By Larry Nichols and George Mather. ......James D. Heiser Pentecostal Currents in American Protestantism. Edited by Edith L. Blumhofer, Russel P. Spittler, and Grant A. Wacker. .......................Grant A. Knepper Heritage inMotion: Readings in the History of the Lutheran Church- Missouri Synod 1962-l995. Edited by August R. Suelflow. ............Grant A. Knepper The "I" in the Storm: A Study of Romans 7. By Michael Paul Middendorf. .................... A. Andrew Das Sin, Death, and the Devil. Edited by Carl E. Braaten and Robert W. Jenson. .................. John T. Pless The Bible in English: John Wyclifie and William Tyndale. By John D. Long. ............Cameron A. MacKenzie Sermons at Court: Politics and Religion in Elizabethan and Jacobean Preaching. -

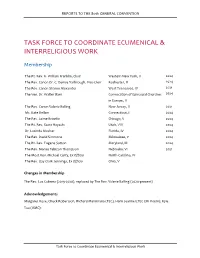

Report to the 80Th General Convention of the Task Force To

REPORTS TO THE 80th GENERAL CONVENTION TASK FORCE TO COORDINATE ECUMENICAL & INTERRELIGIOUS WORK Membership The Rt. Rev. R. William Franklin, Chair Western New York, II 2024 The Rev. Canon Dr. C. Denise Yarbrough, Vice-Chair Rochester, II 2024 The Rev. Canon Sharon Alexander West Tennessee, IV 2021 The Ven. Dr. Walter Baer Convocation of Episcopal Churches 2024 in Europe, II The Rev. Canon Valerie Balling New Jersey, II 2021 Ms. Kate Bellam Connecticut, I 2024 The Rev. Jaime Briceño Chicago, V 2024 The Rt. Rev. Scott Hayashi Utah, VIII 2024 Dr. Lucinda Mosher Florida, IV 2024 The Rev. David Simmons Milwaukee, V 2024 The Rt. Rev. Eugene Sutton Maryland, III 2024 The Rev. Marisa Tabizon Thompson Nebraska, VI 2021 The Most Rev. Michael Curry, Ex Officio North Carolina, IV The Rev. Gay Clark Jennings, Ex Officio Ohio, V Changes in Membership The Rev. Luz Cabrera (2019-2020), replaced by The Rev. Valerie Balling (2020-present) Acknowledgements Margaret Rose; Chuck Robertson, Richard Mammana (TEC), Hank Jeannel (TEC EIR intern); Kyle Tau (UMC); Task Force to Coordinate Ecumenical & Interreligious Work REPORTS TO THE 80th GENERAL CONVENTION Mandate 2018-D055 Coordination of Ecumenical and Interreligious Work Resolved, the House of Deputies concurring, That the 79th General Convention, pursuant to Joint Rule IX.22, create a task force with membership appointed by the Presiding Bishop and the President of the House of Deputies to report annually to the Standing Commission on Structure, Governance, Constitution and Canons (SCSGCC) its work in addressing -

Receiving One Another's Ordained Ministries

Receiving One Another’s Ordained Ministries The Inter-Anglican Standing Commission on Unity, Faith and Order Received by ACC-16, April 2016 Introduction Called to make visible the unity of Christ’s Church, the Churches of the Anglican Communion continue to grow into joyfully demanding relationships with our various ecumenical partners. Experiences of dialogue and praying together have greatly enriched our sense of who we are as Anglicans. In matters of mission, liturgy, theology, spirituality, ethics (and much more besides) the horizon of our Churches has been widened by graced encounters with our Christian sisters and brothers. Anglicans recognise the extent of our participation in a shared life with Christians in other ecclesial traditions, using the biblical language of fellowship or communion (Greek koinonia). The rich theological language of communion underscores how this relationship is understood as a gift of the Triune God. We can neither establish communion with one another, nor break it, but simply recognise and receive it. The communion in which we participate has different degrees. While relationships between Churches may be, for example, of full or of impaired communion, we recognise such communion as a divine gift at the heart of both our intra-Anglican and ecumenical relationships. As these relationships grow stronger, Anglicans inevitably face the question as to whether the degree of communion we share with our ecumenical partners has sufficient theological strength and depth to be articulated as a common calling to fuller communion with the traditions concerned. More specifically, is the communion that we share at a sufficient degree or stage that we might receive one another’s ordained ministries? Anglican Ecclesiology in Context The answer that Anglicans give to this kind of question – and the way in which we respond to the situation out of which it emerges – is rooted in how we understand what it means to be a Church. -

Convention Journal 2010

DIOCESE OF PENNSYLVANIA Journal of the The 227th Convention A “Green” document. This document is being distributed digitally in PDF format in conjunction with the conservation efforts suggested by the National Church. November 6, 2010 Table of Contents Diocese of Pennsylvania Officers, Deans, Bishop’s Staff, Gen. Convention and Provincial Synod Deputies ...................................... 4 Standing Committee ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Diocesan Council ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Diocesan Review Committee ........................................................................................................................ 7 Ecclesiastical Triers ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Committee on Finance and Property ............................................................................................................. 7 Program Budget Committee .......................................................................................................................... 8 COMMISSIONS AND COMMITTEES OF THE DIOCESE Addiction Recovery Resource Committee ..................................................................................................... 8 Anti-Racism Commission ............................................................................................................................. -

Report on the Grounds for Future Relations Between the Church of Sweden and the Episcopal Church Contents

Report on the Grounds for Future Relations between the Church of Sweden and the Episcopal Church Contents 1. Introduction 2. Historical and Contemporary Reasons for Closer Relations 3. Theological and Ecclesiological Bases of Communion 4. Suggestions for Concrete Ways of Cooperating 5. Self-presentation of the Church of Sweden th th 5.1. Medieval Origins (9 – 15 century) th th 5.2. Reformation and Uniformity (16 – 18 century) th th 5.3. Challenges to Uniformity (19 – 20 century) 5.4. Contemporary Situation and Life of the Church 5.4.1. Polity 5.4.2. Liturgy 5.4.3. Missiology 5.4.4. Diaconia 5.4.5. Ecumenism 6. Self-presentation of the Episcopal Church 6.1. The Episcopal Church and the Anglican Ethos 6.2. The Colonial Period (1607 - 1789) 6.2.1. Polity 6.2.2. Liturgy 6.2.3. Doctrine 6.2.4. Missiology 6.3. The National Period (1789 - 1928) 6.3.1. Polity 6.3.2. Liturgy 6.3.3. Doctrine 6.3.4. Missiology 1 6.4. The Modern Period (1928 - Present) 6.4.1. Polity 6.4.2. Liturgy 6.4.3. Doctrine 6.4.4. Missiology 6.5. Current Challenges and Changes 2 Report on the Grounds for Future Relations between the Church of Sweden and the Episcopal Church 1. Introduction This document is a report which aims to present grounds for closer relations between the Church of Sweden and the Episcopal Church. The proposal is not that a new ecumenical agreement on communion between these two churches be written, such as has been the case between a number of Lutheran and Anglican churches. -

Called to Common Mission” Adopted by the Lutheran-Episcopal Coordinating Committee February 5, 2002

Commentary on “Called to Common Mission” Adopted by the Lutheran-Episcopal Coordinating Committee February 5, 2002 “Called to Common Mission” Describes the Relationship of Full Communion between The Episcopal Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Action of the 1999 Churchwide Assembly of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America The Sixth Biennial Churchwide Assembly of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on August 19, 1999, adopted the following: VOTED: Yes–716; No–317 CA99.04.12 RESOLVED, that this Churchwide Assembly of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America accepts “Called to Common Mission: A Lutheran Proposal for a Revision of the Concordat of Agreement,” as amended and set forth below, as the basis for a relationship of full communion to be established between The Episcopal Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America; and be it further RESOLVED, that this Churchwide Assembly of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America requests that Presiding Bishop H. George Anderson of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America convey this action to Presiding Bishop Frank T. Griswold of The Episcopal Church. Action of the 2000 General Convention of The Episcopal Church The Seventy-Third General Convention of The Episcopal Church on July 8, 2000, adopted the following: Resolution A040: Acceptance of "Called to Common Mission" RESOLVED, the House of Deputies concurring, That this 73rd General Convention of The Episcopal Church accepts "Called to Common Mission: A Lutheran Proposal for a Revision of the Concordat of Agreement" as set forth below as the basis for a relationship of full communion to be established between The Episcopal Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America; and be it further RESOLVED, That this 73rd General Convention of The Episcopal Church requests that The Most Rev. -

OEA-ALIC Report

TO LOVE AND SERVE THE LORD Diakonia in the Life of the Church The Jerusalem Report of the Anglican–Lutheran International Commission (ALIC III) TO LOVE AND SERVE THE LORD Diakonia in the Life of the Church The Jerusalem Report of the Anglican–Lutheran International Commission (ALIC III) To Love and Serve the Lord Diakonia in the Life of the Church The Jerusalem Report of the Anglican–Lutheran International Commission (ALIC III) Editorial assistance: Cover: LWF/DTPW staff LWF/OCS staff Anglican Communion Office staff Photo: ACNS/ Neil Vigers Design and Layout: Photo research and design: LWF/OCS staff LWF/DTPW staff Anglican Communion Office staff ISBN 978-2-940459-24-7 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................. 4 I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 6 II. Diakonia Dei/Missio Dei—The Shared Imperative ......................................................... 10 III. Diakonia, Koinonia and the Unity of the Church ........................................................... 16 IV. Historical Approaches to Diakonia and the Diaconate .................................................... 22 Lutheran approaches to diakonia and the diaconate ....................................................................23 Anglican approaches to diakonia and the diaconate .....................................................................25 Diakonia and the -

Are We There Yet? the Task and Function of Full-Communion Coordinating Committees

Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 48:1, Winter 2013 ARE WE THERE YET? THE TASK AND FUNCTION OF FULL-COMMUNION COORDINATING COMMITTEES Mitzi J. Budde PRECIS Most of the bilateral full-communion accords between Protestant denomina- tions in the United States have established a bilateral national coordinating commit- tee to encourage and oversee reception of the agreement. This essay explores the role of these coordinating committees in the implementation of these full- communion agreements throughout the churches. It surveys current bilateral full- communion agreements and explores how the various coordinating committees are chartered, commissioned, and staffed. The characteristics of full-communion coor- dinating committees are described as consultative, collaborative, corroborative, ca- nonical, encouraging, strategic, creative, communicative, generative, and missional. Finally, the essay assesses the challenges and opportunities inherent in implement- ing these ecumenical agreements in the life of the churches. Introduction Over the past twenty years, bilateral full-communion agreements have pro- liferated on the ecumenical scene in the United States. Some of the specific agreements that are currently in play include (in chronological order): The Episcopal Church-the Old Catholic Churches of the Union of Utrecht (1934) The Episcopal Church-The Philippine Independent Church (1961) The Episcopal Church-the Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar, India (1979)1 The United Church of Christ-Christian Church/Disciples of Christ Ecumeni- cal Partnership (1989)2 Evangelical Lutheran Church in America-Presbyterian Church (USA), the Reformed Church in America, and the United Church of Christ (1997)3 Evangelical Lutheran Church in America-the Moravian Church of America, Northern & Southern Provinces (1999)4 ______________ 1The Episcopal Church, Full Communion Partners; available at http://www.episcopalchurch. -

Finding Our Delight in the Lord

Official Text: Finding Our Delight in the Lord Finding Our Delight in the Lord: A Proposal for Full Communion Between The Episcopal Church; the Moravian Church–Northern Province; and the Moravian Church–Southern Province Table of Contents I. Preface II. Introduction III. Foundational Principles IV. Ministry of Bishops V. Reconciliation of Ministries a) Ministries of Oversight b) Ministry of Bishops c) Ministry of Presbyters d) Ministry of Deacons VI. Interchangeability of Clergy VII. Joint Commission VIII. Wider Context IX. Existing Relationships X. Other Dialogues XI. Conclusion XII. Appendices 1 Official Text: Finding Our Delight in the Lord I. Preface Preaching at the opening service of the Second World Conference of Faith and Order in 1937, William Temple (then Archbishop of York and later Archbishop of Canterbury) noted two “great evils” caused by the divisions of the church: The first is that [the divisions] obscure our witness to the one Gospel; the second is that through the division each party to it loses some spiritual treasure, and none perfectly represents the balance of truth, so that this balance of truth is not presented to the world at all.1 It is because of these two “great evils” of Christian disunity that our churches—The Episcopal Church and the Moravian Church in America (Northern and Southern Provinces)—have pursued a formal dialogue resulting in this proposal for full communion, a necessary step toward “the goal of visible unity in one faith and one eucharistic fellowship expressed in worship and common life in Christ.”2 We seek this relationship of full communion so that our mission as Christ’s church will be more effectively fulfilled and each of our communions might be more complete because of the spiritual treasures of the other; and we do this for the sake of the world, “so that the world may believe.”3 We have also been motivated by the ecumenical history and legacy of our two churches.