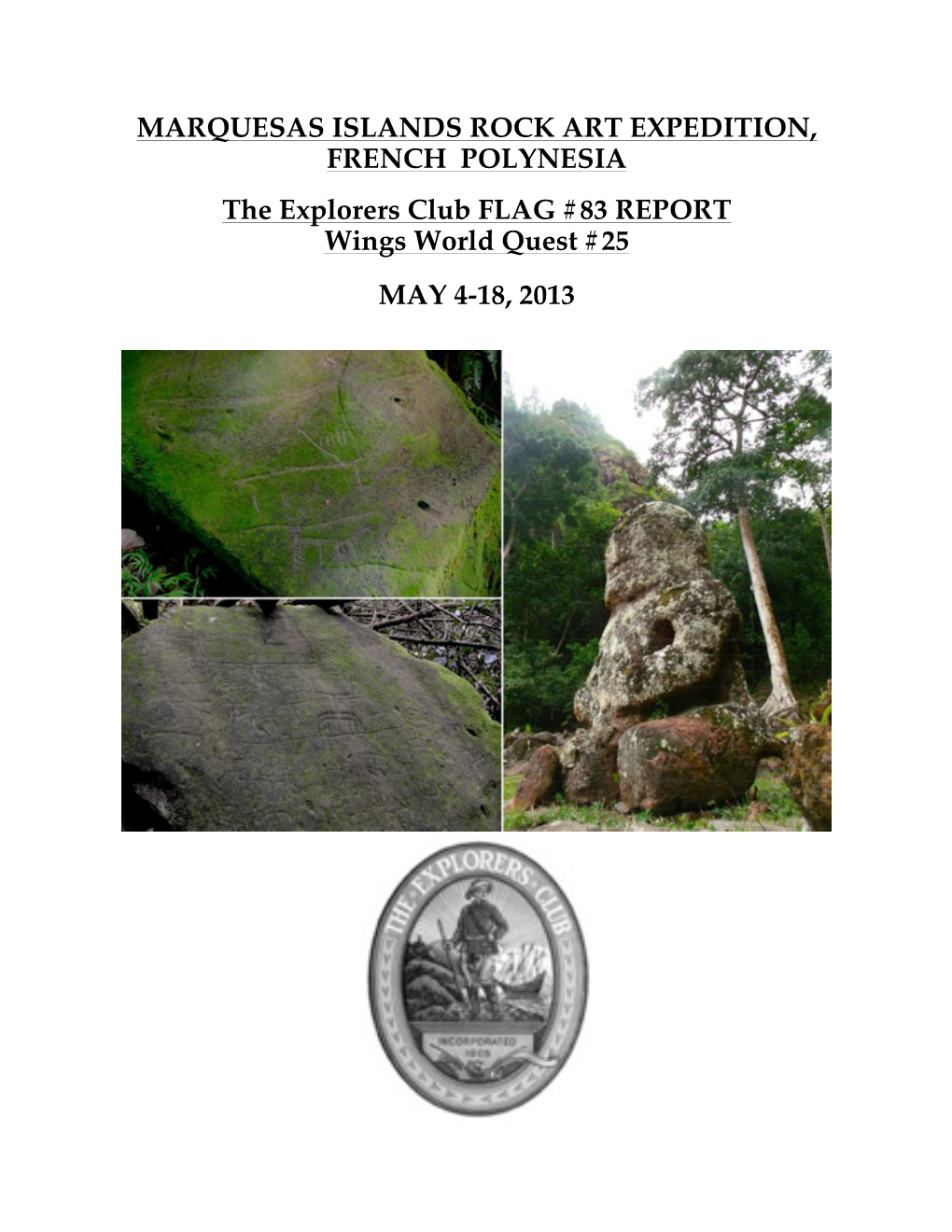

Marquesas Islands Rock Art Expedition, French Polynesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2017.Pdf

MILITARY SEA SERVICES MUSEUM, INC. SEA SERVICES SCUTTLEBUTT December 2017 A message from the President Greetings, The year 2017 was another good year for the Museum. Thanks to our Member's dues, a substantial contribution from our most generous member and contributions from a couple of local patriotic organizations, we will end the year financially sound and feeling confident that we will be able to make any emergency repairs and continue to make improvements to the Museum. As reported in previous Scuttlebutts, most of our major projects have been completed. Our upgraded security system with motion activated cameras inside the Museum and outside the shed John Cecil should be completed this month. The construction of a concrete structure for the mid-1600s British Admiralty Cannon should be completed early next year. I hope everyone has a Merry Christmas and a New Year that is happy, healthy and prosperous. On this Christmas day let's all say a prayer for our troops that can't be home with families and loved ones. They are doing a great job of preventing the spread of terrorism and protecting our freedoms. Please say a prayer for their safe return home. John Military Sea Services entry in Sebring's 2017 Veteran's Day Parade The construction on Fred Carino's boat was done by Fred and his brother Chris. The replica of the bow ornament was done by Mary Anne Lamorte and her granddaughter Dominique Juliano. Military Sea Services Museum Hours of Operation 1402 Roseland Avenue, Sebring, Open: Thursday through Saturday Florida, 33870 Phone: (863) 385-0992 Noon to 4:00 p.m. -

Preliminary Program

Preliminary Program SPSA 2020 Annual Meeting San Juan, Puerto Rico v. 1.0 (10/21/19) 2100 2100 Indigeneity as a Political Concept Thursday Political Theory 8:00am-9:20am Chair Christopher M Brown, Georgia Southern University Participants Indigeneity as Social Construct and Political Tool Benjamin Gregg, University of Texas at Austin Policing the African State: Foreign Policy and the Fall of Self-Determination Hayley Elszasz, University of Virginia Discussant S. Mohsin Hashim, Muhlenberg College 2100 Historical Legacies of Race in Politics Thursday Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 8:00am-9:20am Chair Guillermo Caballero, Purdue University Participants Race and Southern Prohibition Movements Teresa Cosby, Furman University Brittany Arsiniega, Furman University Unintended Consequences?: The Politics of Marijuana Legalization in the United States and its Implications on Race Revathi Hines, Southern University and A&M College No Hablo Español: An Examination of Public Support of Increased Access to Medical Interpreters Kellee Kirkpatrick, Idaho State University James W Stoutenborough, Idaho State University Megan Kathryn Warnement, Idaho State University Andrew Joseph Wrobel, Idaho State University Superfluity and Symbolic Violence: Revisiting Hannah Arendt and the Negro Question in the Era of Mass Incarceration Gabriel Anderson, University of California, Irvine Weaponizing Culture and Women’s Rights: Indigenous Women’s Indian Status in Canada Denise M. Walsh, University of Virginia Discussant Andra Gillespie, Emory University The papers on this -

The Hakaea Beach Site, Marquesan Colonisation, and Models of East Polynesian Settlement

Archaeol. Oceania 45 (2010) 54 –65 The Hakaea Beach site, Marquesan colonisation, and models of East Polynesian settlement MELINDA S. ALLEN and ANDREW J. M cALISTER Keywords: Polynesia, settlement models, coastal geodynamics, climate change, colonisation process, sea level fall Abstract Field explorations at the newly recorded Hakaea Beach site, Nuku also the processes and mechanisms which might account for Hiva, Marquesas Islands were spread across a 12,500 m 2 area on regional patterns of mobility and settlement, is emphasized. the western coastal flat. The site’s geomorphic and cultural history is reconstructed based on nine strata and ten radiocarbon determinations. The Hakaea record illustrates the range of Hakaea Valley powerful environmental processes, including sea level fall, climate change, tsunamis, and tropical storm surges, which have operated Hakaea is a long narrow valley on the windward coast of on Marquesan shorelines for the last 800 years, and the ease with Nuku Hiva (Figure 1). It opens onto a ca. 300 m wide which past human activity can be obscured or erased. The results coralline sand beach (Figure 2) and a deep narrow bay. This highlight the need to systematically search for protected coastal coastline has a dynamic and complex geomorphic history, contexts and geomorphic settings where older surfaces might be with the narrow topography of both the valley and the bay preserved. Radiocarbon assemblages from the 13th century potentially aggravating the impact of terrestrial and marine Hakaea Beach site and seven other early Marquesan sites are forces, both of which have left dramatic signatures on the considered in light of three models of East Polynesian dispersal: 1) contemporary landscape. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

THE DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES AND CHILE 1810-1823 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY BUTLER ALFONSO JONES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ATLANTA, GEORGIA JUNE 1938 / ' ' I // / ii PREFACE The most casual study of the relations between the United States and the Latin American republics will indicate that the great republic in the north has made little effort to either understand the difficulties that have sorely tried her younger and less powerful neighbors or to study their racial characteristics and customs with the friendly appreciation necessary to good relations between states. Nor is it sufficient in a democracy where public opinion plays an important part in foreign affairs to confine know¬ ledge of foreign policies and peoples to the select few who make up the go¬ vernment. Such understanding should be widespread among the peoples them¬ selves, so that public opinion, based upon an intelligent comprehension of the facts, can aot as a lever towards more friendly cobperation, rather than as a spur to jealous and rival aspirations. To bring about this better re¬ lationship, v/hich can be accomplished only by a better mutual understanding, every avenue of approach should be utilized. It is the purpose of this paper to utilize one of the avenues of approach by presenting, in an objective man¬ ner, the story of the early relations of the United States with what, in some respects, is the most powerful of the Latin American nations and, in all respects, is the most stabilized of our South American neighbors. -

Annexe 1 2 SOMMAIRE

Plan DE Développement économique durable 2012-2027 AANNNNEEXXEE 11 SSTTRRUUCCTTUURRAATTIIOONN EETT DDEEVVEELLOOPPPPEEMMEENNTT DDUU TTOOUURRIISSMMEE Étude MaHoc- CREOCEAN - Archipelagoes PDEM 2013 – Annexe 1 2 SOMMAIRE Pages Rapport phase 1 : Diagnostic 5 Introduction 8 Les données de cadrage 13 L'offre touristique actuelle et les projets 25 Le diagnostic de la demande 57 L'organisation touristique et les outils marketing 75 Benchmarking de produits et de destinations 89 Conclusions du diagnostic 93 Annexes 95 Rapport phase 2 : Définition du positionnement de la destination et du produit 179 "Tourisme aux Marquises" Introduction 181 Rappel méthodologique 182 Rappel sur le potentiel de développement touristique des îles Marquises 185 Stratégie marketing du tourisme aux Marquises 188 Axes stratégiques du développement touristique 205 Rapport phase 3 : Plan d’actions opérationnel pour le développement 209 du tourisme aux Marquises Rappel méthodologique 212 Le plan d'actions opérationnel 213 ANNEXES 261 Complément au rapport phase 3 : réponses aux notes du Conseil Communautaire 262 des 31 août et 1er septembre 2012 Calendrier de mise en œuvre 266 Proposition de charte graphique identité Tourisme aux Marquises 268 Exemple de cahier des charges pour l’implantation d’une aire technique pour la 278 plaisance PDEM 2013 – Annexe 1 3 PDEM 2013 – Annexe 1 4 COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES DES ÎLES MARQUISES Structuration et développement du tourisme aux Marquises Rapport de phase 1 Diagnostic Mars 2012 PDEM 2013 – Annexe 1 5 SOMMAIRE Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... -

CRYPTORRHYNCHINAE of the AUSTRAL ISLANDS (Coleoptera, Curculionidae)

CRYPTORRHYNCHINAE OF THE AUSTRAL ISLANDS (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) By ELWOOD C. ZIMMERMAN BERNICE P. BISHOP MUSEUM OCCASIONAL PAPERS VOLUME XII, NUMBER 17 :. ..,," HONOLULU, HAWAII PUBLISHED BY THE MUSEUM October 30, 1936 CRYPTORRHYNCHINAE OF THE AUSTRAL ISLANDS1 2 (COLl';OPTtRA, CURCULIONIDAE) By ELWOOD C. ZIMMER:>IAN INTRODUCTION This paper is based on the collection of Cryptorrhynchinae made by me in the Austral Islands while on the "Mangarevan Expedition to southeastern Polynesia in 1934. The Austral Archipelago is a group of five scattered islands lying to the south of the Society Islands and to the southeast of the Cook Islands (21 0 30' S. to 24° 00' S; 147 0 40' W. to 154 0 55' W.). The general trend of the group is northwest by southeast, and the islands are, in order: Maria, Rimatara, Rurutu, Tubuai, and Raivavae. The northwesternmost island, Maria, is a low coral atoll; the next island to the east, Rimatara, reaches an elevation of about 300 feet, and the following three islands reach elevations of 1,300, 1,309, and 1,434 feet respectively. The devastation of the endemic flora of the group has been extensive. Raivavae has the greatest areas of native vegetation. Tubuai and Rurutu have been so com pletely denuded that there now remain only small pockets of endemic forest near the summits of their highest peaks. The interior of Rimatara has yielded completely to fire and cultivation, while Maria has the typical, widespread flora of the atolls. It is only in the small vestiges of native vegetation that endemic Cryptorrhynchinae can now be found. -

Report for the 2002 Pacific Biological Survey, Bishop Museum Austral Islands, French Polynesia Expedition to Raivavae and Rapa Iti

Rapa K.R. Wood photo New Raivavae Damselfly Sicyopterus lagocephalus: Raivavae REPORT FOR THE 2002 PACIFIC BIOLOGICAL SURVEY, BISHOP MUSEUM AUSTRAL ISLANDS, FRENCH POLYNESIA EXPEDITION TO RAIVAVAE AND RAPA ITI Prepared for: Délégation à la Recherche (Ministère de la Culture, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche), B.P. 20981 Papeete, Tahiti, Polynésie française. Prepared by: R.A. Englund Pacific Biological Survey Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817 March 2003 Contribution No. 2003-004 to the Pacific Biological Survey 2002 Trip Report: Expedition to Raivavae and Rapa, Austral Islands, French Polynesia TABLE OF CONTENTS Résumé ..................................................................................................................................................................iii Abstract.................................................................................................................................................................. iv Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Study Area.............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Aquatic Habitats- Raivavae .............................................................................................................................. 3 Aquatic Habitats- Rapa.................................................................................................................................... -

Mr. Hironui Johnston Thahiti French Polynesia

Ministry of Tourism And Labor, In charge of International Transportation and Institutional relations Innovation and Digital transformation New opportunities in the the sustainable tourism era 31st March 2021 French Polynesia • Oversea collectivity of the French republic • 5.5 million km2 (as vast as western Europe or 49% of continental US ) • 118 islands, 5 archipelagoes, 67 islands inhabited • 278 400 people as of December 2019, 70% on 3 652 businesses (7.5%) Tahiti 11 897 employees (17.7%) • 43 airports About 2 000 self-employed • 25 main touristic islands 12% GDP (18% indirect and induced impacts) 2 Purposes: connect Tahiti to the world/connect the islands Honotua domestic: 5 islands/245 000 inhabitants/70% tourism traffic Natitua north: 20 islands/ 25 000 inhabitants/ 29% tourism traffic 3 Connecting the islands MANATUA, 2020, USD21 600 HONOTUA, 2010, USD 90 000 000: Tahiti-Rarotonga-Aitutaki- 000: Los Angeles-Hawaii-Tahiti Niue-Samoa HONOTUA domestic, 2010: NATITUA South, 2022, USD15 Tahiti-Moorea-Huahine-Raiatea- 000 000: Tahiti-Tubuai-Rurutu Bora Bora NATITUA North, 2018, USD 64 800 000: Tahiti-Kaukura- Asia-Tahiti-Rapa Nui-Chile Rangiroa-Fakarava-Manihi- Makemo-Hao-Takaroa-Hiva Oa- Nuku Hiva + 10 4 Tourism Forum USD200 000 Digital area: Youth, unemployed and entrepreneurs -Tourism contest winners - Workshops - Digital contest - Conferences winners - International - Polynesian tech speakers projects - 4 areas: Digital, - PRISM projects Creation, Training, jobs 5 Arioi Expérience: Tourism Sharing cultural business project expériences -

Marquesan Adzes in Hawai'i: Collections, Provenance

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 outside the Marquesas have never been found in the Marquesan Adzes in Hawai‘i: island group (Allen 2014:11), but this groundbreaking Collections, Provenance, and discovery was spoiled by the revelation that a yachtsman who had visited both places had donated the artifacts, Sourcing and apparently mixed them up before doing so (202). Hattie Le‘a Wheeler Gerrish Researchers with access to other sources of information Anthropology 484 can avoid possible pitfalls. Garanger (1967) laments, Fall 2014 “What amount of dispersed artifacts were illegally exported by the numerous voyagers drawn by the Abstract mirage of the “South Seas” and now irrevocably lost to In 1953, Jack and Leah Wheeler returned to science?” (390). It is my intent to honor the wishes of Hawai'i with 13 adze heads and one stone pounder my maternal grandparents, Jack and Leah Wheeler, that they had obtained during their travels in the Marquesas, the artifacts they (legally) brought home to Hawai'i from Tuamotus, and Society Islands. The rather general the East Pacific not be “irrevocably lost to science.” I provenance of these artifacts presents a challenge will attempt to source their stone artifacts, and discover that illustrates the benefits of combining XRF with what geochemistry can tell us of these tools of uncertain other sources of information, and the limits of current provenance. My experience strengthens my belief that knowledge of Pacific geochemistry. EDXRF reveals that combining non-destructive EDXRF with other sources five of the artifacts are likely made of stone from the of information such as oral history, written accounts, Eiao quarry, and the rest may represent five additional and morphological comparison, enhances the value of sources. -

The Marquesas

© Lonely Planet Publications 199 The Marquesas Grand, brooding, powerful and charismatic. That pretty much sums up the Marquesas. Here, nature’s fingers have dug deep grooves and fluted sharp edges, sculpting intricate jewels that jut up dramatically from the cobalt blue ocean. Waterfalls taller than skyscrapers trickle down vertical canyons; the ocean thrashes towering sea cliffs; sharp basalt pinnacles project from emerald forests; amphitheatre-like valleys cloaked in greenery are reminiscent of the Raiders of the Lost Ark; and scalloped bays are blanketed with desert arcs of white or black sand. This art gallery is all outdoors. Some of the most inspirational hikes and rides in French Polynesia are found here, allowing walkers and horseback riders the opportunity to explore Nuku Hiva’s convoluted hinterland. Those who want to get wet can snorkel with melon- headed whales or dive along the craggy shores of Hiva Oa and Tahuata. Bird-watchers can be kept occupied for days, too. Don’t expect sweeping bone-white beaches, tranquil turquoise lagoons, swanky resorts and THE MARQUESAS Cancun-style nightlife – the Marquesas are not a beach holiday destination. With only a smat- tering of pensions (guesthouses) and just two hotels, they’re rather an ecotourism dream. In everything from cuisine and dances to language and crafts, the Marquesas do feel different from the rest of French Polynesia, and that’s part of their appeal. Despite the trap- pings of Western influence (read: mobile phones), their cultural uniqueness is overwhelming. They also make for a mind-boggling open-air museum, with plenty of sites dating from pre-European times, all shrouded with a palpable historical aura. -

Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology

THE WAR OF 1812 MAGAZINE ISSUE 26 December 2016 Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology Compiled by Ralph Eshelman and Donald Hickey Introduction This War of 1812 Chronology includes all the major events related to the conflict beginning with the 1797 Jay Treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and ending with the United States, Weas and Kickapoos signing of a peace treaty at Fort Harrison, Indiana, June 4, 1816. While the chronology includes items such as treaties, embargos and political events, the focus is on military engagements, both land and sea. It is believed this chronology is the most holistic inventory of War of 1812 military engagements ever assembled into a chronological listing. Don Hickey, in his War of 1812 Chronology, comments that chronologies are marred by errors partly because they draw on faulty sources and because secondary and even primary sources are not always dependable.1 For example, opposing commanders might give different dates for a military action, and occasionally the same commander might even present conflicting data. Jerry Roberts in his book on the British raid on Essex, Connecticut, points out that in a copy of Captain Coot’s report in the Admiralty and Secretariat Papers the date given for the raid is off by one day.2 Similarly, during the bombardment of Fort McHenry a British bomb vessel's log entry date is off by one day.3 Hickey points out that reports compiled by officers at sea or in remote parts of the theaters of war seem to be especially prone to ambiguity and error. -

Jorge Ortiz-Sotelo Phd Thesis

;2<? /81 >42 0<5>5=4 8/@/7 =>/>598 !'+&+#'+)," 6NPGE 9PRIX#=NREKN / >HEQIQ =SBLIRRED FNP RHE 1EGPEE NF ;H1 AR RHE ?MITEPQIRW NF =R$ /MDPEUQ ',,+ 3SKK LERADARA FNP RHIQ IREL IQ ATAIKABKE IM <EQEAPCH.=R/MDPEUQ-3SKK>EVR AR- HRRO-%%PEQEAPCH#PEONQIRNPW$QR#AMDPEUQ$AC$SJ% ;KEAQE SQE RHIQ IDEMRIFIEP RN CIRE NP KIMJ RN RHIQ IREL- HRRO-%%HDK$HAMDKE$MER%'&&()%(,*+ >HIQ IREL IQ OPNRECRED BW NPIGIMAK CNOWPIGHR PERU AND THE BRITISH NAVAL STATION (1808-1839) Jorge Ortiz-Sotelo. Thesis submitted for Philosophy Doctor degree The University of Saint Andrews Maritime Studies 1996 EC A UNI L/ rJ ý t\ jxý DF, ÄNý Jorge Ortiz-Sotelo Peru and the British Naval Station ABSTRACT The protection of British interests in the Pacific was the basic reason to detach a number of Royal Navy's vessels to that Ocean during the Nineteenth Century. There were several British interests in the area, and an assorted number of Britons established in Spanish America since the beginning of the struggle for Independence. Amongst them, merchants was perhaps the most important and influential group, pressing on their government for protection to their trade. As soon as independence reached the western coast of America, a new space was created for British presence. First Valparaiso and afterwards Callao, British merchants were soon firmly established in that part of South America. As had happened in the Atlantic coast, their claims for protection were attended by the British government through the Pacific Squadron, under the flag of the Commander-in-Chief of the South American Station, until 1837, when it was raised to a separate Station.