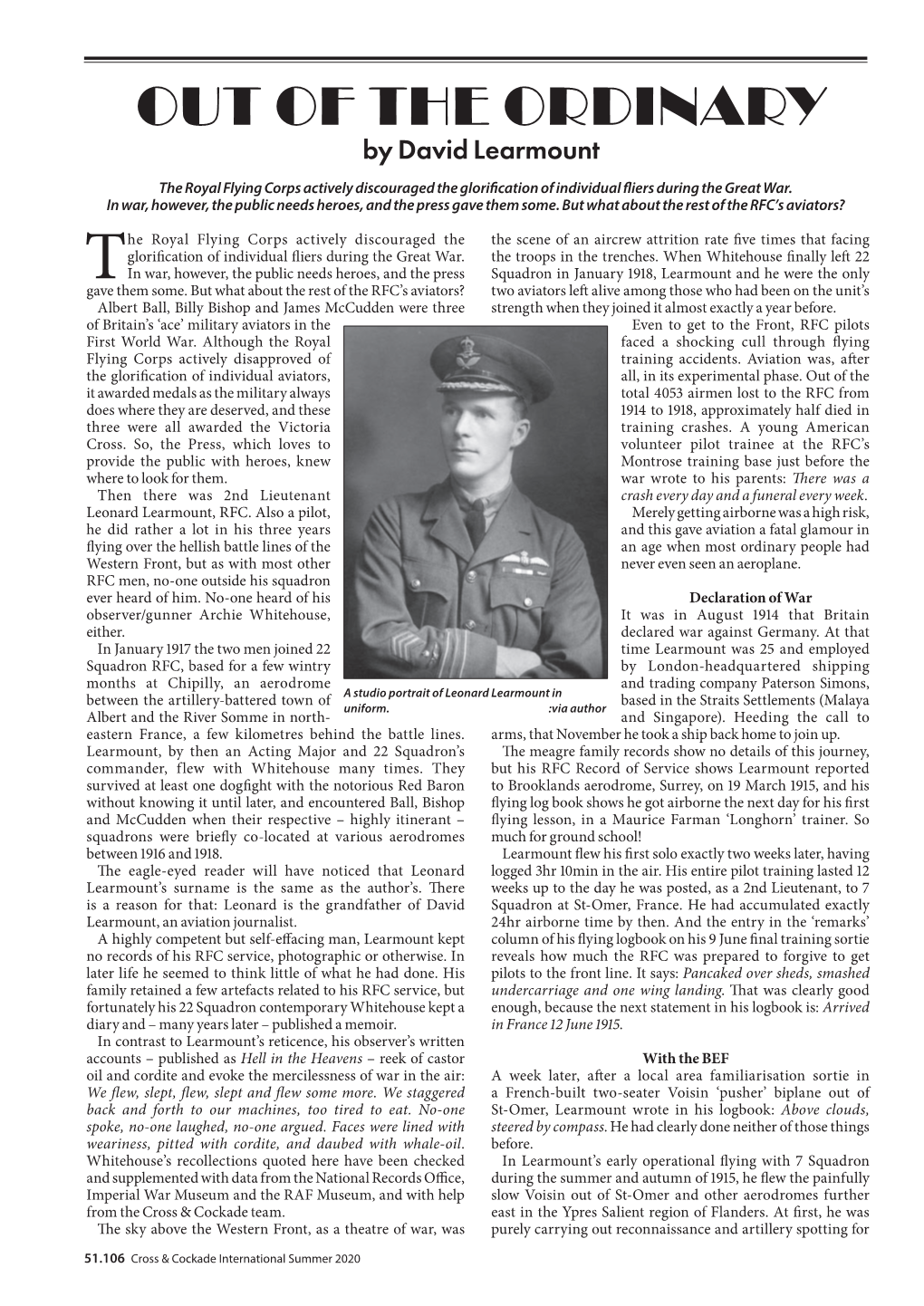

2/Lt Leonard Learmount

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frederick Libby (Part 4 of 8)

The American Fighter Aces Association Oral Interviews The Museum of Flight Seattle, Washington Frederick Libby (Part 4 of 8) Interviewed by: Eugene A. Valencia Interview Date: circa March 1962 2 Abstract: In this eight-part oral history, fighter ace Frederick Libby is interviewed about his life and his military service with the Royal Flying Corps during World War I. In part four, he discusses his time as an observer and pilot with various squadrons in France. Topics discussed include his thoughts on German and British pilots, military life in France and England, and mission logistics for squadrons. The interview is conducted by fellow fighter ace Eugene A. Valencia. Biography: Frederick Libby was born in the early 1890s in Sterling, Colorado. He worked as an itinerant cowboy during his youth and joined the Canadian Army shortly after the outbreak of World War I. Deployed to France in 1915, Libby initially served with a motor transport unit, then volunteered for the Royal Flying Corps. He served as an observer with No. 23 Squadron and No. 11 Squadron, then as a pilot with No. 43 Squadron and No. 25 Squadron. Scoring a number of aerial victories during his RFC career, he became the first American fighter ace. Libby transferred to the United States Army Air Service in 1917 and was medically discharged soon after for spondylitis. As a civilian, he went on to embark on a number of business ventures, including founding the Eastern Oil Company and Western Air Express. Libby passed away in 1970. Biographical information courtesy of: Libby, Frederick. Horses don’t fly: The memoir of the cowboy who became a World War I ace. -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

Franz Losel, a German Photographer Long-Established in Sheerness, Was

SHEPPEY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR Barbed Wire Island Refits and repairs were the main HMS Bulwark, a battleship guarding roles of Sheerness Dockyard the Thames Estuary against possible during the War but invasion, was destroyed by an internal Cadmus-class ships previously explosion while anchored near built there — HMS Espiegle, Clio Sheerness on November 26th 1914. and Odin (bottom right) — Although Armistice Day, Only 12 of its 750 crew survived. earned battle honours in the November 11th 1918, is when Middle East. Sheerness-built hostilities were halted, Sheppey’s HMS Brilliant (top right), a light main celebration of the War’s end cruiser, was also used as a was on June 29th 1919, when the Eastchurch airfield can claim to be the first block ship during the raid on Treaty of Versailles, which set out Royal Naval Air Station and it was here that Sheppey’s strategic location led to German-held Ostend in the peace terms, was signed. the first operational unit sent overseas was it being heavily fortified and Sheppey was attacked by spring 1918. nicknamed Barbed Wire Island. formed under the command of pioneering bombers and airships as Miles of trenches were dug along aviator Charles Samson (right). The base was people at home now found the cliffs and those wanting access used mostly for training but also provided air themselves on the front needed special identity cards — defence. There was also an air gunnery line. The worst attack was ‘Sheppey Passports’. school in Leysdown (below). on June 5th 1917 when 11 people were killed in a raid on Sheerness by Gotha bombers, one of which was shot down and recovered near Barton's Point (right). -

British Identity, the Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2019 A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby S. Whitlock College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Whitlock, Abby S., "A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1276. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1276 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby Stapleton Whitlock Undergraduate Honors Thesis College of William and Mary Lyon G. Tyler Department of History 24 April 2019 Whitlock !2 Whitlock !3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………….. 4 Introduction …………………………………….………………………………… 5 Chapter I: British Aviation and the Future of War: The Emergence of the Royal Flying Corps …………………………………….……………………………….. 13 Wartime Developments: Organization, Training, and Duties Uniting the Air Services: Wartime Exigencies and the Formation of the Royal Air Force Chapter II: The Cultural Image of the Royal Flying Corps .……….………… 25 Early Roots of the RFC Image: Public Imagination and Pre-War Attraction to Aviation Marketing the “Cult of the Air Fighter”: The Dissemination of the RFC Image in Government Sponsored Media Why the Fighter Pilot? Media Perceptions and Portrayals of the Fighter Ace Chapter III: Shaping the Ideal: The Early Years of Aviation Psychology .…. -

“To Fly Is More Fascinating Than to Read About Flying”: British R.F.C. Memoirs of the First World War, 1918-1939 Ian A

Civil War Institute Faculty Publications Civil War Institute 2014 “To fly is more fascinating than to read about flying”: British R.F.C. Memoirs of the First World War, 1918-1939 Ian A. Isherwood Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwifac Part of the European History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Oral History Commons, Public History Commons, and the Social History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Isherwood, Ian A., “’To fly is more fascinating than to read about flying’: British R.F.C. Memoirs of the First World War, 1918-1939.” War, Literature and the Arts 26 (2014), 1-20. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwifac/13 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “To fly is more fascinating than to read about flying”: British R.F.C. Memoirs of the First World War, 1918-1939 Abstract Literature concerning aerial warfare was a new genre created by the First World War. With manned flight in its infancy, there were no significant novels or memoirs of pilots in combat before 1914. It was apparent to British publishers during the war that the new technology afforded a unique perspective on the battlefield, one that was practically made for an expanding literary marketplace. -

The Incomparable Billy Bishop: the Man and the Myths

HISTORY DND Photo NAC AH-740-A DND Photo NAC William Avery Bishop, VC. THE INCOMPARABLE BILLY BISHOP: THE MAN AND THE MYTHS by Lieutenant-Colonel David Bashow Think of the audace of it. acclaimed second book, Winged Peace, much of his vision was embodied in the United Nations International Civil Aviation Maurice Baring Organization (ICAO) in 1947. However, all these achieve- ments would occur long after he won his spurs in the skies over o spoke the renowned British poet and diplomat, the Somme, the Douai Plain and Flanders in 1917 and 1918. Maurice Baring, while serving as private secretary to There, he was the product of his circumstances: a war-weary Major General Hugh Trenchard at Royal Flying Empire in need of a charismatic hero. His war record would Corps Headquarters in France, upon hearing the eventually generate mountains of controversy, but only, for the news of Billy Bishop’s daring dawn raid on a most part, well after his death in 1956. SGerman airfield on 2 June 1917. Indeed, William Avery Bishop, Canada’s first aerial Victoria Cross winner, was auda- Billy Bishop was born in Owen Sound, Ontario, in 1894 of cious. He was also an imperfect human being and a study in upper middle class parents. A “disinterested student with poor contradictions, frequently at odds with the perceptions of an grades” who preferred solitary sports to team efforts, he was adoring public. While often a proud, ambitious risk-taker and, unable to meet the entrance requirements for the University of occasionally, a self-absorbed embellisher of the truth, he was Toronto, and followed his older brother Worth to the Royal also a skilled, courageous and resourceful warrior who served Military College at Kingston in 1911. -

The Happy Warrior: James Thomas Byford Mccudden VC Online

PQsbM [Download free pdf] The Happy Warrior: James Thomas Byford McCudden VC Online [PQsbM.ebook] The Happy Warrior: James Thomas Byford McCudden VC Pdf Free Alex Revell audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1865243 in Books 2015-05-26Original language:English 11.00 x .69 x 8.50l, #File Name: 1935881345304 pages | File size: 21.Mb Alex Revell : The Happy Warrior: James Thomas Byford McCudden VC before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Happy Warrior: James Thomas Byford McCudden VC: 4 of 4 people found the following review helpful. A must read!By Chuck B“The Happy Warrior” is another wonderful book by Alex Revell. As with his previous books, “High in the Empty Blue: The History of 56 Squadron, RFC/RAF 1916-1919”, “Brief Glory: The Life of Arthur Rhys Davids, DSO, MC”, the author weaves together official records, and logbooks, with family letters, diaries, and remembrances of contemporaries to bring a more complete picture of these young men who served in the Royal Flying Corps / Royal Air Force during the 1914-1918 War.In telling the story of James McCudden, possibly the finest pilot and patrol leader of the First World War, the author allows us to catch a glimpse of the man and add context to his accomplishments. To quote directly from “The Happy Warrior”:“To put McCudden’s superlative record still further in perspective it must be remembered that not only was he still a young man, but that he achieved his success in a Britain in which social class was still a dominant feature, which barred many from advancement in both civilian and military life. -

Imperial War Museum WW1 Gallery Quiz

IWM WW1 Gallery Quiz Art. IWM ART935 Wilfred Salmon and the First Blitz Name: 2nd Lt Wilfred Salmon 1917 Ballarat Clarendon College 1 Imperial War Museum Visit Thursday 27th July Art. IWM ART 935 Imperial War Museum Lambeth Find the plaque on the right hand wall of the entrance lobby 1) Was the Imperial War Museum damaged in the Gotha raids? _____________________ 2) On what dates did the raids take place?________________________________________ 3) How many bombs fell ?_____________________________________________________ 4) Were these daytime or night raids?___________________________________________ 5) How many people were killed? _____________________________________________ 7) Wilfred was a driver in the RAFA. Can you find a gun like this? What was it called?______________________ 2 Art. IWMImperial ART 935 War Museum Visit Thursday 27th July The Underworld Walter Bayes 1918 8) What tube station is shown? ________________________________________________ 9) How many sheltered in the tube from 1917-18? Was this more or less than WW2? ___________________________________________________________________________ 10) How many babies/pets can you see in the painting? Babies Pets 11) Why do you think Walter Bayes called his painting, ‘Underworld?’ ___________________________________________________________________________ 12) Can you name 5 Empire countries that provided soldiers for WW1? Label below- 13) How many soldiers did Australia promise to send? Ulster Museum 3 Art. IWMImperial ART 935 War Museum Visit Thursday 27th July 14) Why was Wilfred turned down by the army when he tried to join in September 1914? ___________________________________________________________________________ 15) How much money did Wilfred’s state of Victoria donate in 1914?__________________ 16) Wilfred experienced a mustard gas attack on the Somme. What harm did it do? ___________________________________________________________________________ 17) Wilfred wore a gas mask. -

THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING the BATTLE of the SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: a PYRRHIC VICTORY by Thomas G. Bradbeer M.A., Univ

THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY By Thomas G. Bradbeer M.A., University of Saint Mary, 1999 Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________ Chairperson Theodore A. Wilson, PhD Committee members ____________________ Jonathan H. Earle, PhD ____________________ Adrian R. Lewis, PhD ____________________ Brent J. Steele, PhD ____________________ Jacob Kipp, PhD Date defended: March 28, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Thomas G. Bradbeer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY ___________________ Chairperson Theodore A. Wilson, PhD Date approved March 28, 2011 ii THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME, APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY ABSTRACT The Battle of the Somme was Britain’s first major offensive of the First World War. Just about every facet of the campaign has been analyzed and reexamined. However, one area of the battle that has been little explored is the second battle which took place simultaneously to the one on the ground. This second battle occurred in the skies above the Somme, where for the first time in the history of warfare a deliberate air campaign was planned and executed to support ground operations. The British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was tasked with achieving air superiority over the Somme sector before the British Fourth Army attacked to start the ground offensive. -

Nottinghamshire Aviation Memorials

Nottinghamshire Aviation Memorials Aviation | Aviation Memorials in Nottinghamshire We love to commemorate our aviation heritage. In Nottinghamshire We Love To Commemorate Our Aviation Heritage The diversity of aviation memorial locations across the county is impressive. These memorials are not just at airfield sites, but they can also be found in churches, village halls, on city streets and at remote countryside locations. Some memorials are relatively new, whilst others can trace their origins back Nottinghamshire decades. These memorials, some of them raised through public subscription, reflect the lives of national figures like Albert Ball VC; whilst others are simpler marks of respect that have been erected thanks to the efforts of small groups of individuals. There are even sculptures and pub signs that highlight the county’s contribution to the development of significant aviation technologies. Collectively they play a part in helping to commemorate the county’s aviation heritage. Many individuals had travelled from around the world to air bases in Aviation Memorials Aviation | Nottinghamshire to train as World War II bomber crews. A common bond that joins most of these memorials together is that they commemorate the lives of brave individuals who were lost whilst learning these new skills; often in difficult weather conditions, a long way from home and in a relatively congested airspace, caused by having a lot of airfields so close together. For each of the memorials listed we have provided some background information about the crews involved and the circumstances of the crash; this is merely a snapshot of incidents that are recorded in more detail in books and on websites and we would encourage you to investigate them further. -

Billy Bishop Goes to War

Billy Bishop Goes to War Written and composed by John Gray In Collaboration with Eric Peterson A Guide to the Play Written and compiled by Mark Claxton 1 Contents How to use this guide pg.3 A Canadian stage classic pg.4 Billy Bishop's legacy: History or just his story? pg.5 Meet the artistic team pg.6 Songs and stories: A summary of the play pg.7 For discussion and further exploration pg. 9 2 How to Use This Guide This guide is intended for anyone who would like to enhance their appreciation and understanding of the Globe Theatre's production of Billy Bishop Goes to War. The guide contains a brief history of the play and its reception, an introduction to the Globe's artistic team, a summary of the action in each scene, a few questions intended to encourage open-ended discussion, and some links to online resources for those who wish to explore further. Some of this guide's content may give you information about the play's plot that you'd rather discover yourself while experiencing the show. If you'd like to avoid any potential spoilers, you might want to wait until seeing the play before reading any further. Teachers who are preparing their students to experience the play can provide them with this guide's discussion questions ahead of time -- or first allow them to see the production and then use the questions or other sections of the guide to facilitate further thought and discussion. I hope this guide is both helpful and enjoyable to read. -

Passchendaele Remembered

1917-2017 PASSCHENDAELE REMEMBERED CE AR NT W E T N A A E R R Y G THE JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION FOUNDED 1980 JUNE/JULY 2017 NUMBER 109 2 014-2018 www.westernfrontassociation.com With one of the UK’s most established and highly-regarded departments of War Studies, the University of Wolverhampton is recruiting for its part-time, campus based MA in the History of Britain and the First World War. With an emphasis on high-quality teaching in a friendly and supportive environment, the course is taught by an international team of critically-acclaimed historians, led by WFA Vice-President Professor Gary Sheffield and including WFA President Professor Peter Simkins; WFA Vice-President Professor John Bourne; Professor Stephen Badsey; Dr Spencer Jones; and Professor John Buckley. This is the strongest cluster of scholars specialising in the military history of the First World War to be found in any conventional UK university. The MA is broadly-based with study of the Western Front its core. Other theatres such as Gallipoli and Palestine are also covered, as is strategy, the War at Sea, the War in the Air and the Home Front. We also offer the following part-time MAs in: • Second World War Studies: Conflict, Societies, Holocaust (campus based) • Military History by distance learning (fully-online) For more information, please visit: www.wlv.ac.uk/pghistory Call +44 (0)1902 321 081 Email: [email protected] Postgraduate loans and loyalty discounts may also be available. If you would like to arrange an informal discussion about the MA in the History of Britain and the First World War, please email the Course Leader, Professor Gary Sheffield: [email protected] Do you collect WW1 Crested China? The Western Front Association (Durham Branch) 1917-2017 First World War Centenary Conference & Exhibition Saturday 14 October 2017 Cornerstones, Chester-le-Street Methodist Church, North Burns, Chester-le-Street DH3 3TF 09:30-16:30 (doors open 09:00) Tickets £25 (includes tea/coffee, buffet lunch) Tel No.