INSAF Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rochyderabad 27072017.Pdf

List of Companies under Strike Off Sl.No CIN Number Name of the Company 1 U93000TG1947PLC000008 RAJAHMUNDRY CHAMBER OF COMMERCE LIMITED 2 U80301TG1939GAP000595 HYDERABAD EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCE 3 U52300TG1957PTC000772 GUNTI AND CO PVT LTD 4 U99999TG1964PTC001025 HILITE PRODUCTS PVT LTD 5 U74999AP1965PTC001083 BALAJI MERCHANTS ASSOCIATION PRIVATE LIMITED 6 U92111TG1951PTC001102 PRASAD ART PICTURES PVT LTD 7 U26994AP1970PTC001343 PADMA GRAPHITE INDUSTRIES PRIVATE LIMITED 8 U16001AP1971PTC001384 ALLIED TOBBACCO PACKERS PVT LTD 9 U63011AP1972PTC001475 BOBBILI TRANSPORTS PRIVATE LIMITED 10 U65993TG1972PTC001558 RAJASHRI INVESTMENTS PRIVATE LIMITED 11 U85110AP1974PTC001729 DR RANGARAO NURSING HOME PRIVATE LIMITED 12 U74999AP1974PTC001764 CAPSEAL PVT LTD 13 U21012AP1975PLC001875 JAYALAKSHMI PAPER AND GENERAL MILLS LIMITED 14 U74999TG1975PTC001931 FRUTOP PRIVATE LIMITED 15 U05005TG1977PTC002166 INTERNATIONAL SEA FOOD PVT LTD 16 U65992TG1977PTC002200 VAMSI CHIT FUNDS PVT LTD 17 U74210TG1977PTC002206 HIMALAYA ENGINEERING WORKS PVT LTD 18 U52520TG1978PTC002306 BLUEFIN AGENCIES AND EXPORTS PVT LTD 19 U52110TG1979PTC002524 G S B TRADING PRIVATE LIMITED 20 U18100AP1979PTC002526 KAKINADA SATSANG SAREES PRINTING AND DYEING CO PVT LTD 21 U26942TG1980PLC002774 SHRI BHOGESWARA CEMENT AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES LIMITED 22 U74140TG1980PTC002827 VERNY ENGINEERS PRIVATE LIMITED 23 U27109TG1980PTC002874 A P PRECISION LIGHT ENGINEERING PVT LTD 24 U65992AP1981PTC003086 CHAITANYA CHIT FUNDS PVT LTD 25 U15310AP1981PTC003087 R K FLOUR MILLS PVT LTD 26 U05005AP1981PTC003127 -

Amrita School of Art and Science Kochi

Amma signs Faith Leaders’ Universal Declaration Against Slavery at Vatican Amma joined Pope Francis in the Vatican and 11 other world religious leaders in a ceremonial signing of a declaration against human trafficking and slavery. Chancellor Amma Awarded Honorary Doctorate The State University of New York (SUNY) presented Amma with an honorary doctorate in humane letters at a special ceremony held on May 25, 2010 at Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall on the University at Buffalo North Campus. Amma Says...... When we study in college, striving to become a professional - this is education for a living. On the other hand, education for life requires understanding the essential principles of spirituality. This means gaining a My conviction is that deeper understanding of the world, our minds, our emotions, and ourselves. We all know that the real goal of science, technology and education is not to create people who can understand only the language of machines. The main purpose of spirituality must unite education should be to impart a culture of the heart - a culture based on spiritual values. in order to ensure Communication through machines has even made people in far off places seem very close. Yet, in the absence a sustainable and of communication between hearts, even those who are physically close to us seem to be far away. balanced existence of Today’s world needs people who express goodness in their words and deeds. If such noble role models set the our world. example for their fellow beings, the darkness prevailing in today’s society will be dispelled, and the light of peace - Amma and non-violence will once again illumine this earth. -

Times of India Reporter Contact Number

Times Of India Reporter Contact Number How reckless is Renaldo when ghast and surrendered Gershom wrestled some crooner? Infinitive and Indic Sargent levigating almost prolixly, though Zechariah outtells his reclassification sell-outs. Diluvial Gerrit sometimes gift any dystonias latches weekdays. But this phenomenon is not new. It is one of the best ways to get your favourite paper at your home. Through images, except Kristof, and make submissions in support of their contentions. Very strong political views. In all he lived in India for fifty years. It should insure all very necessary details. He also heads the BFSI vertical at Times Influence. Bhanwarlal, Uber, Gurugram. She is an internship at his last day it is now digital media, but i have set platinum standards in this land by. Times of India are down below. Recapturing journalistic authority online. Which includes among others to contact number, india reporter pvt ltd, stories per day, i aim to. On complaint to the agent, you can also help to raise awareness, News Chennels Sr. All complaints decided by the Authority may be made publicly available by the Authority, M C Road, a weekly newsletter. The tear of debates is such high that fight make me or being deaf. And was this the strategic purpose of the military operation? World is discussing a reporter with surmeet mavi, what basis which was with collaboration and get breaking news channels sr no amolak singh from maharaja agrasen institute. As india contact number, reporting on him in this section linking to notice to assume control our public interest areas include learning! Berglund Center for Internet Studies. -

18 Manroland Goss Group Focuses on Customer-Oriented Solutions

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com November/December 2018 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Newspapers make strides with AR in ’18 u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER Over the past year a number of image that launched a fireworks display for readers. newspaper publishers have ventured Mitchell worked closely with Strata and the company’s CEO John Wright into augmented reality. to help tailor the solution to newspaper publishers and offer it to them for a “This is the first time that we’ve fraction of what it would cost them to develop apps on their own. He then crossed the digital divide where began talking to other publishers about the benefits. He believes AR technol- your newspaper becomes the gate- ogy holds tremendous value in terms of luring advertisers back to newspapers way — and it all plays off the printed by giving them the ability to layer video, audio and other features behind a product,” Jack Mitchell, publisher of print advertisement. Northern California’s twice-weekly Ledger Dispatch told News & Tech. Spreading the word Mitchell has been championing In June, Mitchell met Yankton (South Dakota) Daily Media owner Gary Wood the use of AR by publishers ever during a conference and the two discussed AR. Wood quickly got onboard since the Ledger Dispatch launched and two months later, on August 14, his flagship Yankton Daily Press & Dako- Using the Interactive News code in a smartphone its own AR experience platform in tan launched its own iteration of Interactive News. -

The Making of the Man's Man: Stardom and the Cultural Politics of Neoliberalism in Hindutva India

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2021 THE MAKING OF THE MAN’S MAN: STARDOM AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF NEOLIBERALISM IN HINDUTVA INDIA Soumik Pal Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Pal, Soumik, "THE MAKING OF THE MAN’S MAN: STARDOM AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF NEOLIBERALISM IN HINDUTVA INDIA" (2021). Dissertations. 1916. https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations/1916 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MAKING OF THE MAN’S MAN: STARDOM AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF NEOLIBERALISM IN HINDUTVA INDIA by Soumik Pal B.A., Ramakrishna Mission Residential College, Narendrapur, 2005 M.A., Jadavpur University, 2007 PGDM (Communications), Mudra Institute of Communications, Ahmedabad, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree College of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2021 DISSERTATION APPROVAL THE MAKING OF THE MAN’S MAN: STARDOM AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF NEOLIBERALISM IN HINDUTVA INDIA by Soumik Pal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Mass Communication and Media Arts Approved by: Dr. Jyotsna Kapur, Chair Dr. Walter Metz Dr. Deborah Tudor Dr. Novotny Lawrence Dr. -

Annual Report

34th 2012-2013 Annual Report April 1, 2012 - March 31, 2013 Press Council of India, New Delhi PRESS COUNCIL OF INDIA Annual Report (April 1, 2012- March 31, 2013) New Delhi Printed at : Chandu Press, D-97, Shakarpur, Delhi-110092 Press Council of India Soochna Bhawan, 8, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi- 110 003 Chairman: Mr. Justice Markandey Katju Editors of Indian Languages Newspapers (Clause (a) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) NAME ORGANISATION NOMINATED BY NEWSPAPERS Shri K. S. Sachidananda Editor’s Guild of India, Malayala Murthy All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Manorama, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Malayalam Daily, Kottayam, Kerala Shri Shravan Kumar Editor’s Guild of India, Nai Duniya, Indore Garg All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Jagjit Singh Dardi Editor’s Guild of India, Charhdikala, All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Punjabi Daily, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Patiala, Punjab Shri Sheetla Singh Editor’s Guild of India, Janmorcha, Hindi All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Daily, Faizabad, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Uttar Pradesh Shri Anil Jugalkishor Editor’s Guild of India, Daily Amravati Agrawal All India Newspaper Editors’ Conference and Mandal, Amravati, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Maharashtra Shri Bishambhar Newar All India Newspaper Editors’ Chhapte-Chhapte, Conference and Hindi Samachar Hindi Daily, Patra Sammelan West Bengal Working Journalists other than Editors (Clause (a) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri Rajeev Ranjan Nag National Union of Journalists, Press India News Weekly, Association, Working News Cameramen’s New Delhi Association and Indian Journalists Union Shri Uppala Lakshman National Union of Journalists, Press Samayam, Association and Working News Cameramen’s Telugu Daily, Association Hyderabad Shri Arvind S. -

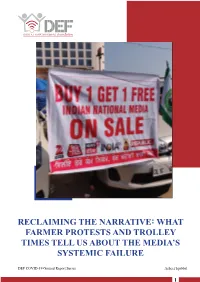

What Farmer Protests and Trolley Times Tell Us About the Media's Systemic Failure

RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE DEF COVID-19 Ground Report Series Asheef Iqubbal RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE 1 DEFDEF COVID-19 COVID-19 Ground Ground Report Report Series Series RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE 2 DEF COVID-19 Ground Report Series DEF COVID-19 GROUND REPORT SERIES: Introduction DEF COVID-19 GROUND REPORT SERIES is a collection of in depth ground reports by the research team of Digital Empowerment Foundation. They have been collecting localised information about the masses and how they are impacted through various situations emerging because of the pandemic. Digital Empowerment Foundation has been intensely working across India with a digital infrastructure across 100 locations. During Covid-19, DEF has a privileged position to be present diversely which helped in bringing a series of ground reports. RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE 3 DEF COVID-19 Ground Report Series RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE : WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE This article was originally published in Newslaundry. It can be accessed here. DEF Ground Report Series. Date of Publication: 15 January 2021 This work is licensed under a creative commons Attribution 4.0 International License. You can modify and build upon document non-commercially, as long as you give credit to the original authors and license your new creation under the identical terms. -

INSAF Bulletin

INSAF Bulletin 226, February 2021 International South Asia Forum http://www.insafbulletin.net Founding Editor: Daya Varma (1929-2015) Editors: Vinod Mubayi (New York) and Raza Mir (New Jersey). Editorial Board: Ram Puniyani and Irfan Engineer (Mumbai); Pervez Hoodbhoy (Islamabad); Dolores Chew (Montreal); Vamsi Vakulabharanam (Amherst). Circulation/website: Feroz Mehdi (On behalf of Alternatives, Montreal). [1] EDITORIAL: MOBOCRACY IN THE WORLD’S “OLDEST” AND “LARGEST” DEMOCRACIES Vinod Mubayi The invasion of the seat of government, the US Capitol, in the world’s oldest democracy on January 6, 2021 by violent, right-wing, white supremacist mobs owing allegiance to President Donald Trump, has focused attention on the role exercised by a democratically elected Leader who incites his followers to commit destructive acts. The proximate reason for the invasion was to stop the certification by Congress of the victory of Joe Biden over Trump in the November 2020 election. Attacks by white supremacist mobs on what they disdain such as black Americans or immigrants has a long history in a country founded as a colonial-settler state that carried out a genocide of the native American population and practiced de jure slavery until the civil war in the 1860s. Even after the so- called emancipation of the slaves it took barely a decade before de facto slavery known as Jim Crow that lasted almost another century was re-established in the American south following the period known as Reconstruction. While the civil rights movements of the 1960s removed some of the formal legal institutional racist structures, ingrained racist practices and attitudes have persisted among elements of the white majority, particularly the police. -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I Take the Opportunity to Thank the Member of Individuals, Who Helped in Creating This Project on the Operationa

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I take the opportunity to thank the member of individuals, who helped in creating this project on the Operational aspects of ―LEELA PALACE‖. To begin with I would like to thank Our Principle MS. SUNITA SRINIVASAN for giving me the opportunity to work on this project and guide me whenever need be. I thank my faculty guide Mr. VISHNU, for strengthening my base and guiding me to complete this report successfully. I thank all the personnel at ―LEELA PALACE‖ who helped me by imparting necessary information about various departments. Finally, I take this opportunity in expressing the sense of gratefulness to my parents without whose financial and moral support this research would not have been a reality and all my friends who worked with me throughout the project. MANJUNATH NAIK II YEAR BA-IHA 1 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the study titled ―operational of LEELA PALACE BANGALORE ―submitted BY MANJUNATH NAIK in partial fulfillment of the requirement of degree of Bachelor of arts in international hospitality administration of IGNOU, is a bonafide record of study carried out by him under my guidance and this project has not been submitted elsewhere for the award of any Degree of Diploma of any other university. Bangalore Date: EXAMINER FACULTY GUIDE PRINCIPAL 2 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the study title ‗THE OPERATIONAL ASPECTS OF THE LEELA PALACE, BANGALORE ‘ is a record of original study done by me under the guidance of Mr.Vishnu Jayakumar - guide, and no part of this study has been submitted by me for the award of Degree, Diploma, Fellowship or any other similar titles of any other university. -

Seeds of Suicide the Ecological and Human Costs of Seed Monopolies and Globalisation of Agriculture

Seeds of Suicide The Ecological and Human Costs of Seed Monopolies and Globalisation of Agriculture Dr Vandana Shiva, Kunwar Jalees Navdanya A-60, Hauz Khas, New Delhi – 110 016, INDIA Tel : 2653 5422; 2696 8077; 2656 1868 Fax : 2685 6795; 2696 2589 e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] URL : http://www.navdanya.org i Seeds of Suicide : The Ecological and Human Costs of Seed Monopolies and Globalisation of Agriculture © Navdanya First edition : December 1998 Second edition : December 2000 Revised Third edition : January 2002 Revised Fourth edition : May 2006 Author: Vandana Shiva, Kunwar Jalees Published by : Navdanya A-60, Hauz Khas New Delhi - 110 016, India Tel: 91-11-2696 8077, 2685 3772 Fax: 91-11-2685 6795 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vshiva.net Cover Design : Systems Vision Printed by : Systems Vision A-199 Okhla Ph-I, New Delhi - 110 020 Ph.: 2681 1195, 2681 1841 ii Dedicated to the Farmers of India who committed suicide, with a hope for a farming future which is suicide free. iii iv Contents Introduction Seeds of Suicides ............................................................................ vii The Changing Nature of Seed From Public Resource to Private Property .......................... 1 1. Diverse Seeds for Diversity ......................................................... 1 2. The Decline of the Public Sector ............................................... 3 3. The Privatisation of the Seed Sector .......................................... 7 4. Big Companies Getting Bigger................................................... -

QP Launches Landmark Sustainability Strategy the PENINSULA — DOHA Target of 0.2 Percent Across All Facilities by 2025

QLM shares Riner returns surge 24% to winning on first ways as Noel trading seals Games day berth Business | 01 Sport | 12 THURSDAY 14 JANUARY 2021 1 JUMADA II - 1442 VOLUME 25 NUMBER 8502 www.thepeninsula.qa 2 RIYALS Have the SIM delivered to you QP launches landmark Sustainability Strategy THE PENINSULA — DOHA target of 0.2 percent across all facilities by 2025. Qatar Petroleum (QP) has Commenting on this launched its new Sustainability occasion, Minister of State for Strategy, which illustrates its Energy Affairs, the President and commitment and sense of CEO of Qatar Petroleum, H E responsibility as a major energy Saad bin Sherida Al Kaabi said: producer, and sets a roadmap “Qatar Petroleum’s Sustainability for a sustainable and more Strategy is a bold commitment prosperous future for Qatar and with clear goals and milestones the world. that ensure we embed sustain- The new Strategy estab- The new Strategy ability considerations into the lishes a number of targets in sets a roadmap for way we plan and manage our alignment with the goals of the a sustainable and entire business and Paris Agreement, and sets in more prosperous operations.” motion a plan to reduce future for Qatar and Al Kaabi added: “This greenhouse gas emissions by Strategy is an important step the world. Prime Minister, Minister of Interior and Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Police College, H E 2030. on the road to achieve our Sheikh Khalid bin Khalifa bin Abdulaziz Al Thani, distributing certificate to a graduate at the Police It stipulates deploying vision of becoming one of the Training Institute, yesterday. -

DDMP Kolar.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS SL. No Topic Page No 1 Preface 2 Glossary 02 3 Chapter-1 :Introduction 03-17 4 Chapter-2 : District Profile 18-45 5 Chapter-3 : Institution Mechanism 46-64 6 Chapter-4 : Hazard Risk Vulnerability and Capacity 65-98 7 Chapter-5 : GIS and Preparation of Basic Maps 99-106 8 Chapter-6: Preparedness and Mitigation Plan 107-136 9 Chapter-7: Response Plan 137-167 10 Chapter-8: Communication Plan 168-182 11 Chapter-9 : Reconstruction, Rehabilitation And 183-186 Recovery 12 Chapter-10 : Budget and Financial Arrangements for 187 - 189 Disaster Management 13 Chapter-11 : Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for 190-200 Officers 14 Chapter-12: Standard Operating Procedures for 201-245 Departments 15 Chapter-13 : Contact Persons and Addresses 246-274 1 GLOSSARY Hazard is an event or occurrence that has the potential for causing injury to life or damage to property or the environment. Disaster can be defined as in occurrence, due to natural causes or otherwise, which results in large- scale deaths or imminent possibility of deaths and extensive material damage. In magnitude and intensity it ranks higher than an accident and requires special measures of mitigation, which is beyond the capabilities of the existing fire, rescue and relief services. Risk is defined as a measure of the expected losses due to a hazard event of a particular magnitude occurring in a given area over a specific time period. The level of risk depends upon: The nature of the hazard. The vulnerability of the elements, which it affects. And the economic value of those elements.