SCIENTISTS in SINGAPORE DISCOVER the NOSE GENE Different Mutations in This Gene Are Also Linked to a Common Type of Muscular Dystrophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daniel Bernstein, MD Associate Dean for Curriculum and Scholarship Stanford University School of Medicine Alfred Woodley Salter and Mabel G

RESEARCHER PROFILES Daniel Bernstein, MD Associate Dean for Curriculum and Scholarship Stanford University School of Medicine Alfred Woodley Salter and Mabel G. Salter Endowed Professor of Pediatrics (Cardiology) Stanford University Former Division Chief, Pediatric Cardiology Former Director, Children’s Heart Center, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford EMAIL [email protected] PROFILE med.stanford.edu/profiles/Daniel-Bernstein LAB murinecvcore.stanford.edu CURRENT RESEARCH EDUCATION/TRAINING Our recent work has focused on the mechanism by which mutations in sarcomeric proteins such MD New York University as myosin lead to the clinical phenotypes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Utilizing human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, with mutations induced by CRISPR/Cas9 PEDIATRICS RESIDENCY Montefiore Medical Center gene editing, we are undertaking a multi-scale approach ranging from structural and function studies on the single myosin molecule, to the individual myofibril, to whole cells and to microengineered MEDICAL EDUCATION FELLOWSHIP Albert Einstein College of Medicine tissues. To better understand cardiomyocyte mechano-transduction, we are applying FRET sensors in critical sarcomeric and junctional proteins. We are also studying a large biobank of myocardial PEDIATRIC CARDIOLOGY FELLOWSHIP UCSF samples from patients with HCM, combining transcriptomics and metabolomics with measurements of mitochondrial function to determine the degree to which HCM is a disease of altered cardiac BOARD CERTIFICATION Pediatrics, ABP energetics. These studies will allow us to correlate findings from hiPSC-CMs with actual patient samples. Another focus of our lab has been on the molecular mechanisms of RV hypertrophy Pediatric Cardiology, ABP and its transition to RV failure, and how this differs from LV failure. -

DPP9 Is an Endogenous and Direct Inhibitor of the NLRP1 Inflammasome That Guards Against Human Auto-Inflammatory Diseases

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/260919; this version posted February 7, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. DPP9 is an endogenous and direct inhibitor of the NLRP1 inflammasome that guards against human auto-inflammatory diseases Franklin L. Zhong1,2,3,*, Kim Robinson2,3, Chrissie Lim1, Cassandra R. Harapas4, Chien- Hsiung Yu4, William Xie2, Radoslaw M. Sobota1, Veonice Bijin Au1, Richard Hopkins1, John E. Connolly1,6,7, Seth Masters4,5 , Bruno Reversade1,2,8,9,10 *, # 1. Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, A*STAR, 61 Biopolis Drive, Proteos, Singapore 138673 2. Institute of Medical Biology, A*STAR, 8A Biomedical Grove, Immunos, Singapore 138648 3. Skin Research Institute of Singapore (SRIS), 8A Biomedical Grove, Immunos, Singapore 138648 4. Inflammation division, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1G Royal Parade, Parkville, VIC, 3052, Australia. 5. Department of Medical Biology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, 3010 Australia 6. Institute of Biomedical Studies, Baylor University, Waco, Texas 76712, USA 7. Department of Microbiology and Immunology, National University of Singapore, 5 Science Drive 2, Singapore 117545 8. Reproductive Biology Laboratory, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Academic Medical Center (AMC), Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam-Zuidoost, Netherlands 9. Department of Paediatrics, National University of Singapore, 1E Kent Ridge Road, Singapore 119228 10. Medical Genetics Department, Koç University School of Medicine, 34010 Istanbul, Turkey * Corresponding authors. F.L.Z., [email protected]; B.R., [email protected] # Lead contact 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/260919; this version posted February 7, 2018. -

Novel Mutations in the Ciliopathy-Associated Gene CPLANE1 (C5orf42) Cause OFD Syndrome Type VI Rather Than Joubert Syndrome

Accepted Manuscript Novel mutations in the ciliopathy-associated gene CPLANE1 (C5orf42) cause OFD syndrome type VI rather than Joubert syndrome Carine Bonnard, Mohammad Shboul, Seyed Hassan Tonekaboni, Alvin Yu Jin Ng, Sumanty Tohari, Kakaly Ghosh, Angeline Lai, Jiin Ying Lim, Ene Choo Tan, Louise Devisme, Morgane Stichelbout, Adila Alkindi, Nazreen Banu, Zafer Yüksel, Jamal Ghoumid, Nadia Elkhartoufi, Lucile Boutaud, Alessia Micalizzi, Maggie Siewyan Brett, Byrappa Venkatesh, Enza Maria Valente, Tania Attié-Bitach, Bruno Reversade, Ariana Kariminejad PII: S1769-7212(17)30410-X DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.03.012 Reference: EJMG 3440 To appear in: European Journal of Medical Genetics Received Date: 30 June 2017 Revised Date: 28 March 2018 Accepted Date: 28 March 2018 Please cite this article as: C. Bonnard, M. Shboul, S.H. Tonekaboni, A.Y.J. Ng, S. Tohari, K. Ghosh, A. Lai, J.Y. Lim, E.C. Tan, L. Devisme, M. Stichelbout, A. Alkindi, N. Banu, Z. Yüksel, J. Ghoumid, N. Elkhartoufi, L. Boutaud, A. Micalizzi, M.S. Brett, B. Venkatesh, E.M. Valente, T. Attié-Bitach, B. Reversade, A. Kariminejad, Novel mutations in the ciliopathy-associated gene CPLANE1 (C5orf42) cause OFD syndrome type VI rather than Joubert syndrome, European Journal of Medical Genetics (2018), doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.03.012. This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. -

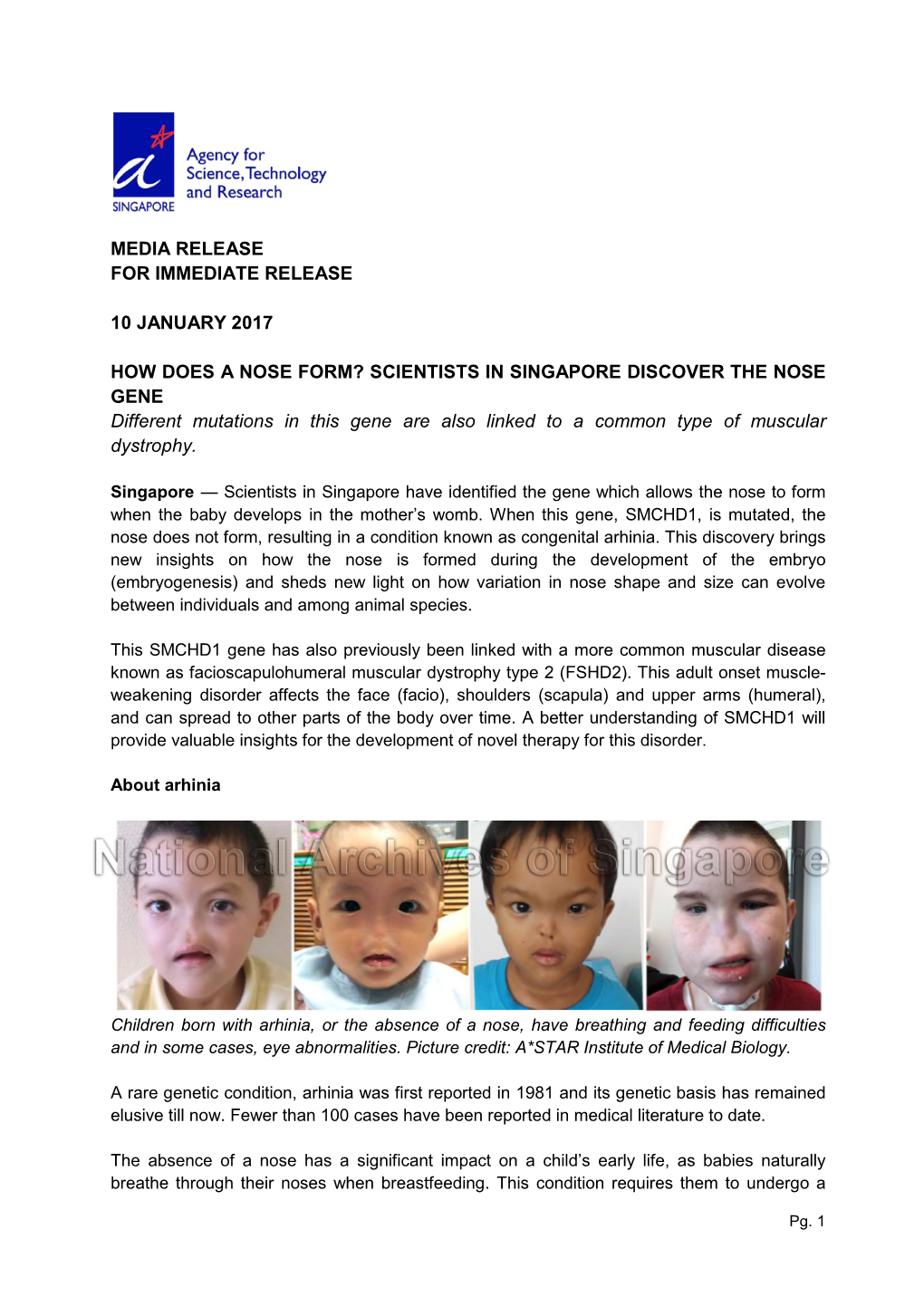

Media Release for Immediate Release

MEDIA RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 22 May 2018 New genetic findings explain how embryos form arms and legs New discovery revises biologists’ understanding of how limbs and lungs develop in humans. The current understanding of limb and lung development in humans does not capture the full picture of the process, according to research published in Nature last week. This paper describes the importance of novel genes for limb development, and shows how perceived wisdom about the process was incomplete. An international group of clinicians and researchers from Singapore, Turkey, France, Portugal and India, studied five families with either limb malformations, or tetra-amelia syndrome that is characterised by the absence of lungs and all four limbs. They found that mutations in the RSPO2 gene lead to incomplete limb development. Until now, the RSPO proteins were believed to only work with their receptors called LGRs. Together, RSPO and LGRs were thought to allow limb formation by blocking two key enzymes ZNRF3 and RNF43. Or so we thought. The team then studied mice lacking all three LGRs required for RSPO2’s function, and found that contrary to what was expected they still developed limbs and lungs normally. This indicates that RSPO2 does not need LGRs — disproving the established understanding of how this is happening. “Our results establish that even without the LGR receptors, RSPO2, can bind to other molecules and constitute a master switch that governs limb development,” says Dr Emmanuelle Szenker-Ravi, a co-first author of the study based at Agency of Science, Technology and Research’s (A*STAR) Institute of Medical Biology (IMB) in Singapore. -

Neuralization of Dissociated Xenopus Cells Is Mediated by Ras/MAPK Activation

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press RESEARCH COMMUNICATION tive signals that act through Receptor Tyrosine kinases Default neural induction: (RTKs). Growth factors that signal via RTKs, such as neuralization of dissociated Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF), Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF), and Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF), are Xenopus cells is mediated potent neural inducers in vertebrates (Wilson and Edlund by Ras/MAPK activation 2001; De Robertis and Kuroda 2004; Stern 2004). RTK signaling activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hiroki Kuroda,1 Luis Fuentealba, Atsushi Ikeda, (MAPK) known as extracellular signal-regulated protein 2 kinase (ERK) via the Ras pathway, and in this way causes Bruno Reversade, and E.M. De Robertis neural induction. Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Department Two disparate views dominate the neural induction of Biological Chemistry, University of California, field at present. Work in the chick embryo has stressed Los Angeles, California 90095-1662, USA the importance of FGF signaling, whereas work in Xeno- pus has tended to emphasize the requirement for anti- Xenopus embryonic ectodermal cells dissociated for BMPs in neural induction (Harland 2000; Stern 2004). three or more hours differentiate into neural tissue in- We have argued that these apparently conflicting obser- stead of adopting their normal epidermal fate. This de- vations can be reconciled through a molecular mecha- nism in which Ras/MAPK phosphorylation regulates the fault type of neural induction occurs in the absence of BMP transducers Smad1/5/8 (De Robertis and Kuroda Spemann’s organizer signals and is thought to be caused 2004). -

Diapositive 1

Apports des nouvelles technologies de la génomique dans les maladies rares Judith Melki Inserm UMR-1169 & University of Paris Sud CHSF, CHU Bicêtre [email protected] 7681 ccatcttctc tttgtgcatg ttggtctccg tgtcccaatt tcccctttct atagggactg cagtcctaat gaattagacc ccaacaaacg acctgatatt aacttgatta cctccataaa 7801 gatcctattt ctaaataagg ccacattttt ttgagatact aggaattagg acatcaatgt atcttttatg tgacagacat ttcaacccat tagagttacc taacctccct cctaacacca 7921 cttccccttt ataaaatgag gataaaagtg ctgacctcac agggctgtgg agaacctggg gctatgcatg tagaaggatt agcacagtgc ctggcacatg gctggaaggc atcaaatgtt 8041 agctagtatt attatgaaat ggggatatag agccttagag ctcaatttat tttgctttgc ttatacagaa gtccatatgg ataacatttt cctccaactc taaagggcat aatgattttt 8161 cataacagcg taagttgatt tttacatctt gtactttaca aaggaactat atatttgaat aaaatttact ttttatttga gtattgccat gtattcatac tatgatacaa ttgccttgaa 8281 taaatacctt actcccagta agtaaataaa ccctaaatgt taaaaatctg aacaatttaa acatggctag aaaatgcacc ttctatatta ttcctaaaat aaaagaaata aaggctctaa 8401 aatgcaatat tgaattcccc caaccatgct gatgtaggta aactgtattt cagatattgg gaaatagcct cataaactga gaagaacacg gcttttagat tcaagtacat atggattcaa 8521 cttccacctt tacccctaca gctctgtgac cagtgggaag ttatgtagct ttgttcagcc ttggtttctt catctgcgaa attaggaaaa taatactcct tcaaaagtga gagagcgtaa 8641 cctgcagtgg atgaatggat aaacaaaatg tgctatgtac atataatgga atattattca gccttaaaaa ggaaggaaat tctgacacac gctataacat ggattaacct tgagaacatt 8761 atgctaagtg aaataaacca gtcatcaata gacagatact gtattattcc acttatgtga ggtacctaaa gtcatcaaat tcatagaggt aaaaaacata aaggcttttg ccaaggtcca 8881 gggggagggt agaatgagga -

R-Spondin Signalling Is Essential for the Maintenance And

RESEARCH ARTICLE R-spondin signalling is essential for the maintenance and differentiation of mouse nephron progenitors Valerie PI Vidal1, Fariba Jian-Motamedi1, Samah Rekima1, Elodie P Gregoire1, Emmanuelle Szenker-Ravi2, Marc Leushacke2, Bruno Reversade2, Marie-Christine Chaboissier1, Andreas Schedl1* 1Universite´ Coˆte d’Azur, Inserm, CNRS, Institut de Biologie Valrose, Nice, France; 2Institute of Medical Biology, A*STAR, Singapore, Singapore Abstract During kidney development, WNT/b-catenin signalling has to be tightly controlled to ensure proliferation and differentiation of nephron progenitor cells. Here, we show in mice that the signalling molecules RSPO1 and RSPO3 act in a functionally redundant manner to permit WNT/b- catenin signalling and their genetic deletion leads to a rapid decline of nephron progenitors. By contrast, tissue specific deletion in cap mesenchymal cells abolishes mesenchyme to epithelial transition (MET) that is linked to a loss of Bmp7 expression, absence of SMAD1/5 phosphorylation and a concomitant failure to activate Lef1, Fgf8 and Wnt4, thus explaining the observed phenotype on a molecular level. Surprisingly, the full knockout of LGR4/5/6, the cognate receptors of R-spondins, only mildly affects progenitor numbers, but does not interfere with MET. Taken together our data demonstrate key roles for R-spondins in permitting stem cell maintenance and differentiation and reveal Lgr-dependent and independent functions for these ligands during kidney formation. *For correspondence: [email protected] Introduction Nephron endowment is a critical factor for renal health and low number of nephrons have been asso- Competing interests: The ciated with chronic kidney disease and hypertension (Bertram et al., 2011). In mammals, nephro- authors declare that no genesis is restricted to the developmental period and involves a dedicated nephrogenic niche at the competing interests exist. -

Driven by Curiosity Under One Roof

WINTER 2012|2013 ISSUE 23 encounters PAGE 13 Deciphering life PAGE 9 Under one roof PAGE 3 Driven by curiosity ANNIVERSARY EMBO to celebrate FEATURE How to help scientists FEATURE 120 past and present EMBO Fellows 50th anniversary in 2014. improve their management skills. attend meeting at Rockefeller University. PAGE 2 PAGE 7 PAGE 5 www.embo.org EMBO 50TH ANNIVERSARY EMBO to celebrate 50th anniversary in 2014 2014 is the 50th anniversary of EMBO and a full programme of events and activities are planned throughout the year. The 50th anniversary is an opportunity to look back on achievements and reflect on progress. It is also a time to celebrate and take a glimpse into the future. MBO, which was founded in 1964, will 2014 is also the 50th anniversary of FEBS, and of these projects is a collection of interviews with celebrate its 50th anniversary in 2014. its French member society, the Société française 10 scientists who have witnessed and influenced EDiverse activities and events are planned to de biochimie et de biologie moléculaire (SFBBM), the history of molecular biology and EMBO. highlight the contributions that EMBO has made will be 100 years old. Instead of holding separate Science writer Georgina Ferry will conduct and to the life sciences over its 50 years of existence – annual conferences, FEBS, EMBO and SFBBM write up the interviews. She is the author of such from talks and meetings to interviews and publi- will celebrate together in 2014 by holding a joint- books as Max Perutz and the Secret of Life and cations. -

DPP9 Deficiency: an Inflammasomopathy Which Can Be Rescued by Lowering NLRP1/IL-1 Signaling

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.31.21250067; this version posted February 3, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. DPP9 deficiency: an Inflammasomopathy which can be rescued by lowering NLRP1/IL-1 signaling 1,2,$ 3,$ 4,$ 4 Cassandra R. HARAPAS , Kim S. ROBINSON , Kenneth LAY , Jasmine WONG , 5 6,7,8 6 Annick RAAS-ROTHSCHILD , Bertrand BOISSON , Scott B. DRUTMAN , Pawat 1,2 9 10 1,2 LAOHAMONTHONKUL , Devon BONNER , Mark GORRELL , Sophia DAVIDSON , 1,2 11 12 Chien-Hsiung YU , Hulya KAYSERILI , Nevin HATIPOGLU , Jean-Laurent 6,7,8,13,14 15 3,* CASANOVA , Jonathan A. BERNSTEIN , Franklin L. ZHONG , Seth L. 1,2,* 4,10,16* MASTERS , Bruno REVERSADE Affiliations: 1. Inflammation Division, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, Australia 2. Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia 3. SRIS, A*STAR, Singapore 4. Genome Institute of Singapore (GIS), A*STAR, Singapore 5. The Institute for Rare Diseases, The Edmond and Lily Safra Children's Hospital, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel; Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel 6. St. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Rockefeller Branch, The Rockefeller University, New York, USA 7. Paris University, Imagine Institute, Paris, France 8. Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Disease, Necker Branch, INSERM U1163, Paris, France 9. Center for Undiagnosed Diseases, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. -

Mitochondrial Peptide BRAWNIN Is Essential for Vertebrate Respiratory Complex III Assembly

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14999-2 OPEN Mitochondrial peptide BRAWNIN is essential for vertebrate respiratory complex III assembly Shan Zhang1, Boris Reljić 2,12, Chao Liang 1,12, Baptiste Kerouanton1,12, Joel Celio Francisco 3, Jih Hou Peh1, Camille Mary 4, Narendra Suhas Jagannathan 5, Volodimir Olexiouk 6, Claire Tang1, Gio Fidelito 1, Srikanth Nama7, Ruey-Kuang Cheng8, Caroline Lei Wee 9, Loo Chien Wang9, Paula Duek Roggli 10, Prabha Sampath 11, Lydie Lane 4, Enrico Petretto 5, Radoslaw M. Sobota 9, Suresh Jesuthasan 8,9, Lisa Tucker-Kellogg 3,5, Bruno Reversade 7,9, Gerben Menschaert6, Lei Sun 1, David A. Stroud 2 & ✉ Lena Ho 1,7 1234567890():,; The emergence of small open reading frame (sORF)-encoded peptides (SEPs) is rapidly expanding the known proteome at the lower end of the size distribution. Here, we show that the mitochondrial proteome, particularly the respiratory chain, is enriched for small proteins. Using a prediction and validation pipeline for SEPs, we report the discovery of 16 endogenous nuclear encoded, mitochondrial-localized SEPs (mito-SEPs). Through functional prediction, proteomics, metabolomics and metabolic flux modeling, we demonstrate that BRAWNIN, a 71 a.a. peptide encoded by C12orf73, is essential for respiratory chain complex III (CIII) assembly. In human cells, BRAWNIN is induced by the energy-sensing AMPK pathway, and its depletion impairs mitochondrial ATP production. In zebrafish, Brawnin deletion causes complete CIII loss, resulting in severe growth retardation, lactic acidosis and early death. Our findings demonstrate that BRAWNIN is essential for vertebrate oxidative phosphorylation. We propose that mito-SEPs are an untapped resource for essential regulators of oxidative metabolism. -

Scientific Release 6 December 2013 A*Star Scientists

SCIENTIFIC RELEASE 6 DECEMBER 2013 A*STAR SCIENTISTS DISCOVER NOVEL HORMONE ESSENTIAL FOR HEART DEVELOPMENT This unusual discovery could aid cardiac repair and provide new therapies to common heart diseases and hypertension 1. Scientists at A*STAR’s Institute of Medical Biology (IMB) and Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology (IMCB) have identified a gene encoding a hormone that could potentially be used as a therapeutic molecule to treat heart diseases. The hormone - which they have chosen to name ELABELA - is only 32 amino-acids long, making it amongst the tiniest proteins made by the human body. 2. The team led by Dr Bruno Reversade carried out experiments to determine ELABELA’s function, since its existence was hitherto unsuspected. Using zebrafish designed to specifically lack this hormone, they uncovered that ELABELA is indispensable for heart formation. Zebrafish embryos without this gene had rudimentary or no heart at all (see Figure 1). Their results were published in the 5 December 2013 online issue of Developmental Cell. 3. Deficiencies in hormones are the cause of many diseases, such as the loss of insulin or insulin resistance, that results in diabetes, and irregularities in appetite and satiety hormones that can cause obesity. Hormones are known to control functions such as sleep, appetite and fertility. However, this is the first time that scientists have revealed the existence of a conserved1 hormone playing such an early role during embryogenesis, effectively orchestrating the development of an entire organ. 4. The team also found that ELABELA uses a receptor previously believed to be specific to APELIN, a blood-pressure controlling hormone. -

A Homozygous Loss-Of-Function CAMK2A Mutation Causes Growth

RESEARCH ARTICLE A homozygous loss-of-function CAMK2A mutation causes growth delay, frequent seizures and severe intellectual disability Poh Hui Chia1†*, Franklin Lei Zhong1,2†*, Shinsuke Niwa3,4†, Carine Bonnard1, Kagistia Hana Utami5, Ruizhu Zeng5, Hane Lee6,7, Ascia Eskin6,7, Stanley F Nelson6,7, William H Xie1, Samah Al-Tawalbeh8, Mohammad El-Khateeb9, Mohammad Shboul10, Mahmoud A Pouladi5,11, Mohammed Al-Raqad8, Bruno Reversade1,2,12,13* 1Institute of Medical Biology, Immunos, Singapore; 2Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Proteos, Singapore; 3Frontier Research Institute for Interdisciplinary Sciences, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan; 4Graduate School of Life Sciences, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan; 5Translational Laboratory in Genetic Medicine, Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore, Singapore; 6Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States; 7Department of Human Genetics, David Geffen School of Medicine University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States; 8Queen Rania Paediatric Hospital, King Hussein Medical Centre, Royal Medical Services, Amman, Jordan; 9National Center for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Genetics, Amman, Jordan; 10Al-Balqa Applied University, Faculty of Science, Al-Salt, Jordan; 11Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of *For correspondence: 12 [email protected] Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore; Department of 13 (PHC); Paediatrics, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore; Medical [email protected] Genetics Department, Koc¸ University School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey (FLZ); [email protected] (BR) †These authors contributed equally to this work Abstract Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMK2) plays fundamental roles in synaptic plasticity that underlies learning and memory.