Boraginaceae) Endemic to Sardinia (Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anchusa L. and Allied Genera (Boraginaceae) in Italy

Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology Official Journal of the Societa Botanica Italiana ISSN: 1126-3504 (Print) 1724-5575 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tplb20 Anchusa L. and allied genera (Boraginaceae) in Italy F. SELVI & M. BIGAZZI To cite this article: F. SELVI & M. BIGAZZI (1998) Anchusa L. and allied genera (Boraginaceae) in Italy, Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology, 132:2, 113-142, DOI: 10.1080/11263504.1998.10654198 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/11263504.1998.10654198 Published online: 18 Mar 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 29 View related articles Citing articles: 20 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tplb20 Download by: [Università di Pisa] Date: 05 November 2015, At: 02:31 PLANT BIOSYSTEMS, 132 (2) 113-142, 1998 Anchusa L. and allied genera (Boraginaceae) in Italy F. SEL VI and M. BIGAZZI received 18 May 1998; revised version accepted 30 July 1998 ABSTRACT - A revision of the Italian entities of Anchusa and of the rdated genera Anchusella, Lycopsis, Cynoglottis, Hormuzakia and Pentaglottis was carried out in view of the poor systematic knowledge of some entities of the national flora. The taxonomic treatment relies on a wide comparative basis, including macro- and micromorphological, karyological, chorological and ecological data. After a general description of some poorly known microCharacters of vegetative and reproductive structures, analytical keys, nomenclatural types, synonymies, descriptions, distribution maps and iconographies are provided for each entity. -

Anchusa Crispa Viv. Subsp. Crispa

IN SITU CONSERVATION - SPECIES INFORMATION SHEET Project partner: National Botanical Conservatory of Corsica of the Office of the Environment of Corsica Island CORSICA Species name (Family) Anchusa crispa Viv. subsp. crispa (Boraginaceae) Common name French: Buglosse crépue Plant description V Herbaceous taxa, hispid, initially in a rosette of hard leaves, prostrate on the sand, then presenting with floriferous stems, leafy, littlely branched from the rosette. Leaved leaves, oblong, sinuated-crispy, from 4-10 mm broad to 3-20 cm long. Terminal inflorescences fomed uniparous scorpioid cymes, elongating during the flowering period, with bearing flowers onaxils of small hairy bracts. Small, actinomorphous, gamosepal calyx flowers and blue gamopetal corolla. Fruits: 4 achenes per flower, with a very small aril. V Flowering occurs between April and May. Fruiting from late May to September. Pollination is done by insects and the seed spread is generally barochorial, even some cases of zoochory is signaled due to ants and caws. V A. crispa is a sabulicolous, heliophilous, nitrophilous or subnitrophilic plant, xerophilic, well tolerant of sea salt, but very sensitive to sand cover during storms Distribution This species is endemic of Corsica and Sardinia. There are: 2 populations located in the east coast of Corsica and 8 populations located on the sand along the North West of Sardinia. Map Two subspecies of A. crispa exist in Corsica: A. crispa valincoana and A. crispa crispa . The crispa subspecies is only present on the east coast of the island. There are only two populations highly threatened by tourism activities. IN SITU CONSERVATION - SPECIES INFORMATION SHEET Legal status A. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Common Bugloss Anchusa Officinalis

Common bugloss Other common names: Common anchusa, alkanet, bee USDA symbol: ANOF Anchusa officinalis bread, ox’s tongue, starflower, common borage, orchanet, ODA rating: B and T Introduction: Common bugloss is native to the Mediterranean region. It was cultivated in medieval gardens and is now naturalized throughout Europe and in much of eastern North America. It's considered invasive in the Pacific Northwest. This herb has numerous medicinal uses as well as its historical use as a dye plant. Distribution in Oregon: The first report in Oregon was in 1933 from Wallowa County. It continues to be a problem in the Imnaha River Valley and other locations in NE Oregon. Description: A perennial herb, common bugloss flowers from May to October. It grows one to two feet tall. The stems and leaves are fleshy and coarsely hairy. Basal leaves are lance shaped while upper leaves are progressively smaller up the stem, stalk-less and clasping. It has blue to purple flowers with white throats and five petals. The fiddleneck flower stem uncoils as each bud opens. Its fruit is a four-chambered nutlet and each nutlet contains one seed. One plant can produce an average of 900 seeds, which remain viable for several years. Common bugloss is similar to blueweed, Echium vulgare and can be easily confused. The taproot produces a purplish red dye. Impacts: This plant invades alfalfa fields, pastures, pine forests, rangeland, riparian, and waste areas. The fleshy stalks can cause hay bales to mold. Large, very dense stands can occur, offering strong competition to native plant communities. -

Tmcm1de1.Pdf

Departament de Biologia Facultat de Ciències Hybridization patterns in Balearic endemic plants assessed by molecular and morphological markers — Ph. D. Thesis — Miquel Àngel Conesa Muñoz Supervisors: Dr. Maurici Mus Amézquita (Universitat de les Illes Balears) Dr. Josep Antoni Rosselló Picornell (Universitat de València) May 2010 Palma de Mallorca El doctor Maurici Mus Amézquita, professor titular de la Universitat de les Illes Balears, i el doctor Josep Antoni Rosselló Picornell, professor titular de la Universitat de València, CERTIFIQUEN: Que D. Miquel Àngel Conesa Muñoz ha realitzat, baix la seva direcció en el Laboratori de Botànica de la Universitat de les Illes Balears i en el Departament de Botànica del Jardí Botànic de la Universitat de València, el treball per optar al grau de Doctor en Biologia de les Plantes en Condicions Mediterrànies, amb el títol: “HYBRIDIZATION PATTERNS IN BALEARIC ENDEMIC PLANTS ASSESSED BY MOLECULAR AND MORPHOLOGICAL MARKERS” Considerant finalitzada la present memòria, autoritzem la seva presentació amb la finalitat de ser jutjada pel tribunal corresponent. I per tal que així consti, signem el present certificat a Palma de Mallorca, a 27 de maig de 2010. Dr. Maurici Mus Dr. Josep A. Rosselló 1 2 A la meva família, als meus pares. 3 4 Agraïments - Acknowledgements En la vida tot arriba. A moments semblava que no seria així, però aquesta tesi també s’ha acabat. Per arribar avui a escriure aquestes línies, moltes persones han patit amb mi, per mi, o m’han aportat el seu coneixement i part del seu temps. Així doncs, merescut és que els recordi aquí. Segurament deixaré algú, que recordaré quan ja sigui massa tard per incloure’l. -

Boraginaceae) Taxa from Turkey

Pak. J. Bot., 42(4): 2231-2247, 2010. MORPHOLOGICAL, ANATOMICAL AND NUMERICAL STUDIES ON SOME ANCHUSA L. (BORAGİNACEAE) TAXA FROM TURKEY TULAY AYTAS AKCIN1*, SENAY ULU1 AND ADNAN AKCIN2 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Art and Science, University of Ondokuz Mayıs, 55139 Samsun, Turkey 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Art and Science, University of Amasya, 05100 Amasya, Turkey Abstract This study used numerical methods to illustrate, describe and assess the taxonomic significance of morphological and anatomical features of three Anchusa species,, Anchusa undulata subsp. hybrida (Ten.) Coutinho, A. azurea Miller var. azurea and A. pusilla Guşul., collected from Northern Turkey. In this morphological study, it was determined that the ratio of calyx lobe to the calyx length and the arrangement of the anthers in the corolla tube were important characters in separating the taxa morphologically. Anatomical studies supported these morphological observations. Further, statistical analysis showed that corolla tube length was not important as a taxonomic character. However, the ratio of calyx lobe length to calyx length was the most significant character in distinguishing the taxa. The first two principal components explained 45.69 % of the total variance. Principal component analysis showed that no separation could be obtained among the species, although A. azurea specimens tended to compose a different group. Introduction Anchusa L., (Boraginaceae) is one of the major genera of flowering plants, consisting of about 170 taxa native to temperate and subtropical areas of the Old World. The major diversity centre of Anchusa is the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula (Selvi & Bigazzi, 2003). The present great form diversity in this heterogeneous genus has generated variable interpretations at both species and generic level (Guşuleac, 1927, 1928, 1929; Chater, 1972; Greuter et al., 1984; Brummit, 1992; Selvi & Bigazzi, 1998). -

A Common Threat to IUCN Red-Listed Vascular Plants in Europe

Tourism and recreation: a common threat to IUCN red-listed vascular plants in Europe Author Ballantyne, Mark, Pickering, Catherine Marina Published 2013 Journal Title Biodiversity and Conservation DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-013-0569-2 Copyright Statement © 2013 Springer. This is an electronic version of an article published in Biodiversity and Conservation, December 2013, Volume 22, Issue 13-14, pp 3027-3044. Biodiversity and Conservation is available online at: http://link.springer.com/ with the open URL of your article. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/55792 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Manuscript 1 Tourism and recreation: a common threat to IUCN red-listed vascular 1 2 3 4 2 plants in Europe 5 6 7 8 3 *Mark Ballantyne and Catherine Marina Pickering 9 10 11 12 4 Environmental Futures Centre, School of Environment, Griffith University, Gold Coast, 13 14 5 Queensland 4222, Australia 15 16 17 18 6 *Corresponding author email: [email protected], telephone: +61(0)405783604 19 20 21 7 22 23 8 24 25 9 26 27 28 10 29 30 11 31 32 12 33 34 13 35 36 37 14 38 39 15 40 41 16 42 43 17 44 45 46 18 47 48 19 49 50 20 51 52 21 53 54 55 22 56 57 23 58 59 24 60 61 62 63 64 65 25 Abstract 1 2 3 4 26 Tourism and recreation are large industries employing millions of people and contribute over 5 6 27 US$2.01 trillion to the global economy. -

Food Plant Quality of Cynoglossum Officinale and Herbivory by Ethmia Bipunctella (Lepidoptera, Ethmiidae)

FOOD PLANT QUALITY OF CYNOGLOSSUM OFFICINALE AND HERBIVORY BY ETHMIA BIPUNCTELLA (LEPIDOPTERA, ETHMIIDAE) by ADRIANA H. PRINS1, RONALD M. LAAN, JANA VERBOOM1 and BEN VERBOOM (Departmentof PopulationBiology, Universityof Leiden, P.O. Box 9516, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands) ABSTRACT The oligophagous lepidoptcran Ethmia bipunctellaF. (Lepidoptera: Ethmiidae) occurs in low numbers in Meijendel, the Netherlands, in spite of the great abundance of its host plant Cynoglossumofficinale L. In this study, we examine the importance of food plant quality on individual performance of E. bipunctella,and discuss the impact on its population density. Grazing by E. bipunctellareduced the growth of plants in a growth room. In the field, flowering plants rather than rosettes were chosen for oviposition. In a choice ex- periment, larvae preferred undamaged rather than damaged leaves, suggesting that herbivory causes a rapid fall in plant acceptability. However, the larvae grew equally well on damaged and undamaged leaves. Our observations imply a role for alkaloids: flowering plants have a much lower alkaloid content than rosettes; and plants with eggs in the field had a lower alkaloid content than plants without eggs. KEY WORDS:alkaloids, Cynoglossumofficinale, Ethmia bipunctella, food quality, her- bivory, Lepidoptera. INTRODUCTION For decades, regulation of population density in the field has been a central question in ecology. Predators and parasites have sometimes been implicated (LAWTON & McNEILL, 1979; STRONG et al., 1984), but in other studies abiotic factors such as climatic conditions and the number of overwintering sites have been given more attention. Also, competition for limiting resources may be important in determining population size (STRONC et al., 1984). -

Anchusa Crispa Subsp. Valincoana (Boraginaceae), Une Nouvelle Sous-Espèce Endémique De Corse

Notes et contributions à la flore de Corse, Contribution 43 Anchusa crispa subsp. valincoana (Boraginaceae), une nouvelle sous-espèce endémique de Corse Guilhan Paradis, Carole Piazza & Yann Quilichini Abstract PARADIS, G., C. PIAZZA & Y. QUILICHINI (2018). Anchusa crispa subsp. valincoana Paradis, Piazza & Quilichini (Boraginaceae), a new subs- pecies endemic to Corsica. Candollea 73: 201 – 207. In French, English and French abstracts. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15553/c2018v732a4 Anchusa crispa subsp. valincoana Paradis, Piazza & Quilichini (Boraginaceae), a new endemic subspecies of the littoral of the western coast of Corsica is described and illustrated. It includes four sub-populations around the Gulf of Valinco, near Propriano. It differs by several morphological characters from Anchusa crispa Viv. subsp. crispa, present on two sites of the Corsican east coast, south of Solenzara and in several localities of the north-west coast of Sardinia, notably by its reddish flowering stems, subglabrous lower surface of leaves, bracts with subglabrous upper surface and glabrous below and its flowers with dark blue corolla. It also differs from Anchusa crispa subsp. maritima (Vals.) Selvi & Bigazzi, a Sardinian endemic, located on some sites of the north coast of Sardinia, a taxon with brownish or greenish flowering stems, linear leaves and bracts with upper surface minutely pubescent. Résumé PARADIS, G., C. PIAZZA & Y. QUILICHINI (2018). Anchusa crispa subsp. valincoana (Boraginaceae), une nouvelle sous-espèce endémique de Corse. Candollea 73: 201 – 207. En français, résumés anglais et français. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15553/ c2018v732a4 Anchusa crispa subsp. valincoana Paradis, Piazza & Quilichini (Boraginaceae), une nouvelle sous-espèce endémique du littoral de la côte occidentale corse, est décrite et illustrée. -

Anchusa Crispa Viv. L’Essentiel Du Plan National D’Actions 2012-2016

Agir pour Anchusa crispa Viv. L’essentiel du plan national d’actions 2012-2016 Ministère de l’Ecologie, du Développement durable, des Transports et du Logement www.developpement-durable.gouv.fr Sommaire La bugLossE crépuE, unE EspècE EnDéMiquE à airE de réparTiTion rEsTrEinte 6 unE EspècE aDapTéE a son MiLiEu de viE 12 unE EspècE En DangEr 14 unE EspècE sous haute survEillancE 18 PLAN NATIONAL D’ACTIONS | ANCHUSA CRISPA 2012-2016 Résumé Anchusa crispa Viv. ou buglosse crépue (Boraginaceae), espèce rare et protégée, est une QU’EST-CE QU’UN PLAN endémique corso-sarde à aire de distribution très NATIONAL D’ACTIONS ? restreinte. En Sardaigne, sur les 9 populations (PNA) recensées, 3 ont aujourd’hui disparu. En Corse, il existe aujourd’hui 6 populations : 4 sur la côte Dans le cadre du Grenelle de occidentale, dans le golfe du Valinco (une petite l’Environnement, un des grands station ayant disparu en 1999) et 2 sur la côte thèmes de réflexion a été la lutte orientale, au sud de Solenzara. Trois de ces six contre la perte de la biodiversité. stations sont menacées de disparition à court ou Pour parvenir à cet objectif, il a moyen terme. été décidé la réalisation de PNA pour 131 espèces présentes sur le Les effectifs sont très variables d’une année territoire national et considérées sur l’autre en raison des conditions climatiques comme « en danger critique d’ex- (fortes sécheresses ou, au contraire, pluviométrie tinction » sur la liste mondiale de importante, tempêtes). Néanmoins, les effectifs l’UICN (Union Internationale pour globaux semblent en augmentation depuis 10 la Conservation de la Nature). -

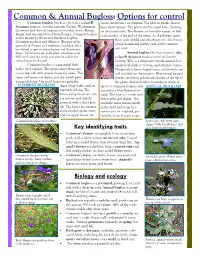

Common & Annual Bugloss: Options for Control

Common & Annual Bugloss: Options for control Common bugloss (Anchusa officinalis), a class-B sessile (no petiole), or clasping. The blue to purple flowers designate noxious weed in Lincoln County, Washington. have white throats. The petals are five equal lobes, forming Common and Annual bugloss are member of the Borage an un-curved tube. The flowers are found in cymes, or heli- family, and was introduced from Europe. Common bugloss coid clusters, at the end of the stems. As the flowers open, is also known by the names Anchusa bugloss, these coils unfold and straighten out. The fruit is Common anchusa and Alkanet. Because of its pretty blue flowers and medicinal and dye use, it a four chambered nutlet; each nutlet contains has found a spot in many home and flower gar- one seed. dens. Unfortunately, each plant produces over Annual bugloss (Anchusa arvensis) , also 900 seeds and the seeds can remain viable for a class-B designate noxious weed in Lincoln several years in the soil. County, WA. is a diminutive weedy annual. It is Common bugloss is a perennial herb a leafy herb with erect stems and alternate leaves. with a deep taproot. The plant ranges from one The petiolate lance-shaped leaves are bristly hairy to two feet tall, with several flowering stems. The and crinkled on the margins. Blue funnel-formed stems and leaves are fleshy, and the overall plant flowers are borne in helicoid clusters at the tip of is coarsely hairy. The basal leaves are petiolate the plant. Annual bugloss is similar in many re- COMMON BUGLOSS (have a leaf stalk), and are spects to common bugloss and ANNUAL BUGLOSS narrowly oblong. -

Global Conservation Translocation Perspectives: 2021. Case Studies from Around the Globe

Global conservation Global conservation translocation perspectives: 2021 translocation perspectives: 2021 IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group Global conservation translocation perspectives: 2021 Case studies from around the globe Edited by Pritpal S. Soorae IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group (CTSG) i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or any of the funding organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. IUCN is pleased to acknowledge the support of its Framework Partners who provide core funding: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark; Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland; Government of France and the French Development Agency (AFD); the Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea; the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad); the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the United States Department of State. Published by: IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group, Environment Agency - Abu Dhabi & Calgary Zoo, Canada. Copyright: © 2021 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Soorae, P. S.