Voice Training and the Royal National Theatre Rena Cook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

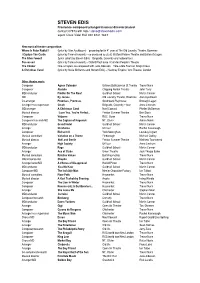

STEVEN EDIS Freelance Composer/Arranger/Musical Director/Pianist Contact 07973 691168 / [email protected] Agent Clare Vidal Hall 020 8741 7647

STEVEN EDIS Freelance composer/arranger/musical director/pianist contact 07973 691168 / [email protected] agent Clare Vidal Hall 020 8741 7647 New musical theatre composition: Where Is Peter Rabbit? (lyrics by Alan Ayckbourn) – preparing for its 4 th year at The Old Laundry Theatre, Bowness I Capture The Castle (lyrics by Teresa Howard) – co-produced by (& at) Watford Palace Theatre and Bolton Octagon The Silver Sword (lyrics (also!) by Steven Edis) – Belgrade, Coventry and national tour Possessed (lyrics by Teresa Howard) – Oxford Playhouse / Camden People's Theatre The Choker One-act opera co-composed with Jude Alderson – Tête-a-tête Festival. King's Cross A Christmas Carol (lyrics by Susie McKenna and Steven Edis) – Hackney Empire / Arts Theatre, London Other theatre work: Composer Agnes Colander Ustinov,Bath/Jermyn St Theatre Trevor Nunn Composer Aladdin Chipping Norton Theatre John Terry MD/conductor Fiddler On The Roof Guildhall School Martin Connor MD By Jeeves Old Laundry Theatre, Bowness Alan Ayckbourn Co-arranger Promises, Promises Southwark Playhouse Bronagh Lagan Arranger/mus.supervisor Crush Belgrade, Coventry + tour Anna Linstrum MD/arranger A Christmas Carol Noel Coward Phelim McDermott Musical director I Love You, You're Perfect... Frinton Summer Theatre Ben Stock Composer Volpone RSC, Swan Trevor Nunn Composer/research/MD The Captain of Köpenick NT, Olivier Adrain Noble MD/conductor Grand Hotel Guildhall School Martin Connor Arranger Oklahoma UK tour Rachel Kavanaugh Composer Richard III York/Nottingham Loveday Ingram -

Savoring the Classical Tradition in Drama

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA MEMORABLE PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD I N P R O U D COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE PLAYERS, NEW YORK CITY THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION JIM DALE ♦ Friday, January 24 In the 1950s and ’60s JIM DALE was known primarily as a singer and songwriter, with such hits as Oscar nominee “Georgy Girl” to his credit. Meanwhile he was earning plaudits as a film and television comic, with eleven Carry On features that made him a NATIONAL ARTS CLUB household name in Britain. Next came stage roles like 15 Gramercy Park South Autolycus and Bottom with Laurence Olivier’s National Manhattan Theatre Company, and Fagin in Cameron Mackintosh’s PROGRAM AT 6:00 P.M. Oliver. In 1980 he collected a Tony Award for his title Admission Free, But role in Barnum. Since then he has been nominated for Reservations Requested Tony, Drama Desk, and other honors for his work in such plays as Candide, Comedians, Joe Egg, Me and My Girl, and Scapino. As if those accolades were not enough, he also holds two Grammy Awards and ten Audie Awards as the “voice” of Harry Potter. We look forward to a memorable evening with one of the most versatile performers in entertainment history. RON ROSENBAUM ♦ Monday, March 23 Most widely known for Explaining Hitler, a 1998 best-seller that has been translated into ten languages, RON ROSENBAUM is also the author of The Secret Parts of Fortune, Those Who Forget the Past, and How the End Begins: The Road to a Nuclear World War III. -

Samson Agonistes Performed by Iain Glen and Cast 1 Introduction - on a Festival Day 8:55 2 Chorus 1: This, This Is He

POETRY UNABRIDGED John Milton Samson Agonistes Performed by Iain Glen and cast 1 Introduction - On a Festival Day 8:55 2 Chorus 1: This, this is he... 3:19 3 Samson: I hear the sound of words... 2:16 4 Chorus 1: Tax not divine disposal, wisest Men... 1:45 5 Samson: That fault I take not on me... 2:03 6 Chorus 1: Thy words to my remembrance bring... 2:33 7 Manoa: Brethren and men of Dan, for such ye seem... 3:11 8 Samson: Appoint not heavenly disposition, Father... 2:56 9 Manoa: I cannot praise thy Marriage choices, Son... 3:36 10 Manoa: With cause this hope relieves thee... 4:22 11 Chorus 1: Desire of wine and all delicious drink... 4:05 12 Samson: O that torment should not be confin’d... 2:45 13 Chorus 3: Many are the sayings of the wise... 3:07 14 Chorus 3: But who is this, what thing of Sea or Land? 1:14 15 Dalila: With doubtful feet and wavering resolution... 2:05 16 Dalila: Yet hear me Samson; not that I endeavour... 6:47 17 Samson: I thought where all thy circling wiles would end... 7:32 2 18 Chorus 1: She’s gone, a manifest Serpent by her sting... 3:24 19 Samson: Fair days have oft contracted wind and rain. 0:48 20 Harapha: I come not Samson, to condole thy chance... 7:15 21 Samson: Among the Daughters of the Philistines... 3:15 22 Chorus 1: His Giantship is gone somewhat crestfall’n.. -

June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace

No. 495 - June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace Nothing like a Dame (make that two!) The VW’s Shakespeare party this year marked Shakespeare’s 452nd birthday as well as the 400th anniversary of his death. The party was a great success and while London, Stratford and many major cultural institutions went, in my view, a bit over-bard (sorry!), the VW’s party was graced by the presence of two Dames - Joan Plowright and Eileen Atkins, two star Shakespeare performers very much associated with the Old Vic. The party was held in the Old Vic rehearsal room where so many greats – from Ninette de Valois to Laurence Olivier – would have rehearsed. Our wonderful Vice-President, Nickolas Grace, introduced our star guests by talking about their associations with the Old Vic; he pointed out that we had two of the best St Joans ever in the room where they would have rehearsed: Eileen Atkins played St Joan for the Prospect Company at the Old Vic in 1977-8; Joan Plowright played the role for the National Theatre at the Old Vic in 1963. Nickolas also read out a letter from Ronald Pickup who had been invited to the party but was away in France. Ronald Pickup said that he often thought about how lucky he was to have six years at the National Theatre, then at Old Vic, at the beginning of his career (1966-72) and it had a huge impact on him. Dame Joan Plowright Dame Joan Plowright then regaled us with some of her memories of the Old Vic, starting with the story of how when she joined the Old Vic school in 1949 part of her ‘training’ was moving chairs in and out of the very room we were in. -

March 2016 Conversation

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD IN COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE WNDC IN WASHINGTON THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION DIANA OWEN ♦ Tuesday, February 23 As we commemorate SHAKESPEARE 400, a global celebration of the poet’s life and legacy, the GUILD is delighted to co-host a WOMAN’S NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC CLUB gathering with DIANA OWEN, who heads the SHAKESPEARE BIRTHPLACE TRUST in Stratford-upon-Avon. The TRUST presides over such treasures as Mary Arden’s House, WITTEMORE HOUSE Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, and the home in which the play- 1526 New Hampshire Avenue wright was born. It also preserves the site of New Place, the Washington mansion Shakespeare purchased in 1597, and in all prob- LUNCH 12:30. PROGRAM 1:00 ability the setting in which he died in 1616. A later owner Luncheon & Program, $30 demolished it, but the TRUST is now unearthing the struc- Program Only , $10 ture’s foundations and adding a new museum to the beautiful garden that has long delighted visitors. As she describes this exciting project, Ms. Owen will also talk about dozens of anniversary festivities, among them an April 23 BBC gala that will feature such stars as Dame Judi Dench and Sir Ian McKellen. PEGGY O’BRIEN ♦ Wednesday, February 24 Shifting to the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY, an American institution that is marking SHAKESPEARE 400 with a national tour of First Folios, we’re pleased to welcome PEGGY O’BRIEN, who established the Library’s globally acclaimed outreach initiatives to teachers and NATIONAL ARTS CLUB students in the 1980s and published a widely circulated 15 Gramercy Park South Shakespeare Set Free series with Simon and Schuster. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2021

Jan 21 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) did not gather in New York to celebrate the Great Detective’s 167th birthday this year, but the somewhat shorter long weekend offered plenty of events, thanks to Zoom and other modern technol- ogy. Detailed reports will be available soon at the web-site of The Baker Street Irregulars <www.bakerstreetirregulars.com>, but here are few brief paragraphs to tide you over: The BSI’s Distinguished Speaker on Thursday was Andrew Lycett, the author of two fine books about Conan Doyle; his topic was “Conan Doyle’s Questing World” (and close to 400 people were able to attend the virtual lecture); the event also included the announcement by Steve Rothman, editor of the Baker Street Journal, of the winner of the Morley-Montgomery Award for the best article the BSJ last year: Jessica Schilling (for her “Just His Type: An Analysis of the Découpé Warning in The Hound of the Baskervilles”). Irregulars and guests gathered on Friday for the BSI’s annual dinner, with Andrew Joffe offering the traditional first toast to Nina Singleton as The Woman, and the program continued with the usual toasts, rituals, and pap- ers; this year the toast to Mrs. Hudson was delivered by the lady herself, splendidly impersonated by Denny Dobry from his recreation of the sitting- room at 221B Baker Street. Mike Kean (the “Wiggins” of the BSI) presented the Birthday Honours (Irregular Shillings and Investitures) to Dan Andri- acco (St. Saviour’s Near King’s Cross), Deborah Clark (Mrs. Cecil Forres- ter), Carla Coupe (London Bridge), Ann Margaret Lewis (The Polyphonic Mo- tets of Lassus), Steve Mason (The Fortescue Scholarship), Ashley Polasek (Singlestick), Svend Ranild (A “Copenhagen” Label), Ray Riethmeier (Mor- rison, Morrison, and Dodd), Alan Rettig (The Red Lamp), and Tracy Revels (A Black Sequin-Covered Dinner-Dress). -

Saluting the Classical Tradition in Drama

SALUTING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ILLUMINATING PRESENTATIONS BY The Shakespeare Guild IN COLLABORATION WITH The National Arts Club The Corcoran Gallery of Art The English-Speaking Union Woman’s National Democratic Club KATHRYN MEISLE Monday, February 6 KATHRYN MEISLE has just completed an extended run as Deborah in ROUNDABOUT THEATRE’s production of A Touch of the Poet, with Gabriel Byrne in the title part. Last year she delighted that company’s audiences as Marie-Louise in a rendering of The Constant Wife that starred Lynn Redgrave. For her performance in Tartuffe, with Brian Bedford and Henry Goodman, Ms. Meisle won the CALLOWAY AWARD and was nominated for a TONY as Outstanding Featured Actress. Her other Broadway credits include memorable roles in London Assur- NATIONAL ARTS CLUB ance, The Rehearsal, and Racing Demon. Filmgoers will recall Ms. Meisle from You’ve Got Mail, The Shaft, and Rosewood. Home viewers 15 Gramercy Park South Manhattan will recognize her for key parts in Law & Order and Oz. And those who love the classics will cherish her portrayals of such heroines as Program, 7:30 p.m. Celia, Desdemona, Masha, Olivia at ARENA STAGE, the GUTHRIE THEATER, MEMBERS, $25 OTHERS, $30 LINCOLN CENTER, the NEW YORK SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL, and other settings. E. R. BRAITHWAITE Thursday, February 23 We’re pleased to welcome a magnetic figure who, as a young man from the Third World who’d just completed a doctorate in physics from Cambridge, discovered to his consternation that the color of his skin prevented him from landing a job in his chosen field. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85054-4 - The Cambridge Companion to David Hare Edited by Richard Boon Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to david hare David Hare is one of the most important playwrights to have emerged in the UK in the last forty years. This volume examines his stage plays, television plays and cinematic films, and is the first book of its kind to offer such comprehen- sive and up-to-date critical treatment. Contributions from leading academics in the study of modern British theatre sit alongside those from practitioners who have worked closely with Hare throughout his career, including former Director of the National Theatre Sir Richard Eyre. Uniquely, the volume also includes a chapter on Hare’s work as journalist and public speaker; a personal mem- oir by Tony Bicat,ˆ co-founder with Hare of the enormously influential Portable Theatre; and an interview with Hare himself in which he offers a personal ret- rospective of his career as a film maker which is his fullest and clearest account of that work to date. A complete list of books in the series is at the back of this book. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85054-4 - The Cambridge Companion to David Hare Edited by Richard Boon Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO DAVID HARE EDITED BY RICHARD BOON University of Hull © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85054-4 - The Cambridge Companion to David Hare Edited by Richard Boon Frontmatter More information cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521615570 C Cambridge University Press 2007 This publication is in copyright. -

Samantha Bond

Samantha Bond Height: 5' 6.5" [168.91 cm.] Eye Color: Blue Hair Color: Red Training: Bristol Old Vic THEATRE The Lie Alice Menier Chocolate Factory Lindsay Posner Dirty Rotten Scoundrels Muriel Eubanks Savoy Theatre Jerry Mitchell Passion Play Nell Duke of Yorks Theatre David Levaux What The Butler Saw Mrs Prentice Vaudeville Sean Foley King James Readings NT James Dacre An Ideal Husband Mrs. Cheveley The Vaudeville Lindsay Posner Arcadia Hannah Duke of Yorks Theatre David Levaux Donkeyís Years Lady Driver Comedy Theatre Jeremy Sams Rubinsteinís Kiss Hesther Hampstead Theatre James Phillips Woman Of No Importance Lady Arbuthnot Haymarket Theatre Adrian Noble Macbeth Lady Macbeth Albery Theatre Ed Hall Vagina Monologues New Ambassadors Irina brown Amyís View* Amy Broadway Richard Eyre Memory Of Water Mary Tour and West End Terry Johnson Amyís View Amy NT & West End Richard Eyre The Ends Of The Earth Cathy NT Andrei Serban Three Tall Women 3rd Lady Robert Fox Ltd Anthony Page The Cid INFANTA National Theatre Jonathan Kent A Winter's Tale Hermione RSC Adrian Noble As You Like It Rosalind & Celia RSC David Thacker Man Of The Moment Jill Globe Alan Ayckbourn Much Ado About Nothing Beatrice Tour & Phoenix Judi Dench Les Liaisons Dangereuses Mme de Tourvel Ambassadors Howard Davies Romeo & Juliet Juliet Lyric Studio Kenneth Branagh Never In My Lifetime The Wife Soho Poly Susan Hogg FILM Cold Blood Legacy Eight 35 Frederic Petitjean A Winter Prince Hallmark Ernie Barbarash Bunch Of Amateurs Trademark Andy Cadiff Yes Adventure pictures Sally Potter -

A Film by Sally Potter

Official Selection Toronto International Film Festival Telluride Film Festival Mongrel Media presents YES A film by Sally Potter with Joan Allen, Simon Abkarian, Sam Neill and Shirley Henderson (UK/USA, 95 minutes) Distribution 1028 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] High res stills may be downloaded from http://mongrelmedia.com/press.html CONTENTS MAIN CREDITS 3 SHORT SYNOPSIS 4 LONG SYNOPSIS 4-5 SALLY POTTER ON YES 6-10 SALLY POTTER ON THE CAST 11 ABOUT THE CREW 12-14 ABOUT THE MUSIC 15 CAST BIOGRAPHIES 16-18 CREW BIOGRAPHIES 19-21 DIRECTOR’S BIOGRAPHY 22 PRODUCERS’ BIOGRAPHIES 23 GREENESTREET FILMS 24-25 THE UK FILM COUNCIL 26 END CREDITS 27-31 2 GREENESTREET FILMS AND UK FILM COUNCIL PRESENT AN ADVENTURE PICTURES PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH STUDIO FIERBERG A FILM BY SALLY POTTER Y E S Written and directed by SALLY POTTER Produced by CHRISTOPHER SHEPPARD ANDREW FIERBERG Executive Producers JOHN PENOTTI PAUL TRIJBITS FISHER STEVENS CEDRIC JEANSON JOAN ALLEN SIMON ABKARIAN SAM NEILL SHIRLEY HENDERSON SHEILA HANCOCK SAMANTHA BOND STEPHANIE LEONIDAS GARY LEWIS WIL JOHNSON RAYMOND WARING Director of Photography ALEXEI RODIONOV Editor DANIEL GODDARD Production Design CARLOS CONTI Costume Design JACQUELINE DURRAN Sound JEAN-PAUL MUGEL VINCENT TULLI Casting IRENE LAMB Line Producer NICK LAWS 3 SHORT SYNOPSIS YES is the story of a passionate love affair between an American woman (Joan Allen) and a Middle-Eastern man (Simon Abkarian) in which they confront some of the greatest conflicts of our generation – religious, political, and sexual.