Promotion of Family Enrollment in an Urban Family Practice Residency Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pilot House-2005-0037036

FOR OHF USE IMPORTANT NOTICE LL1 THIS AGENCY IS REQUESTING DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION THAT IS NECESSARY TO ACCOMPLISH THE STATUTORY 2005 PURPOSE AS OUTLINED IN 210 ILCS 45/3-208. DISCLOSURE STATE OF ILLINOIS OF THIS INFORMATION IS MANDATORY. FAILURE TO PROVIDE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTHCARE AND FAMILY SERVICES ANY INFORMATION ON OR BEFORE THE DUE DATE WILL FINANCIAL AND STATISTICAL REPORT FOR RESULT IN CESSATION OF PROGRAM PAYMENTS. THIS FORM LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIES HAS BEEN APPROVED BY THE FORMS MANAGEMENT CENTER. (FISCAL YEAR 2005) I. IDPH Facility ID Number: 0037036 II. CERTIFICATION BY AUTHORIZED FACILITY OFFICER Facility Name: Pilot House I have examined the contents of the accompanying report to the Address: 1111 Washington Avenue, Box 369 Cairo 62914 State of Illinois, for the period from 1/1/05 to 12/31/05 Number City Zip Code and certify to the best of my knowledge and belief that the said contents are true, accurate and complete statements in accordance with County: Alexander applicable instructions. Declaration of preparer (other than provider) is based on all information of which preparer has any knowledge. Telephone Number: 618 734-3706 Fax # 618 833-4993 Intentional misrepresentation or falsification of any information IDPA ID Number: 37-1272696001 in this cost report may be punishable by fine and/or imprisonment. Date of Initial License for Current Owners: 08/25/88 (Signed) Officer or (Date) Type of Ownership: Administrator (Type or Print Name) Richard Stroh of Provider VOLUNTARY,NON-PROFIT X PROPRIETARY GOVERNMENTAL (Title) Asst. Comptroller Charitable Corp. Individual State Trust Partnership County (Signed) IRS Exemption Code X Corporation Other (Date) "Sub-S" Corp. -

2215 LOCUST ST Proposal: Construct Roof Deck with Pilot House

Address: 2215 LOCUST ST Proposal: Construct roof deck with pilot house; replace side and rear windows; install siding on rear bay Review Requested: Final Approval Owner: Thomas Jay Rush and Meriam Zandi Applicant: Jeffrey Wyant, Wyant Architecture LLC History: 1872 Individual Designation: None District Designation: Rittenhouse Fitler Historic District, Contributing, 2/8/1995 Staff Contact: Allyson Mehley, [email protected] BACKGROUND: 2215 Locust Street is a three-story residential building constructed in 1872 and is contributing to the Rittenhouse Fitler Historic District. This application for final approval proposes to construct a roof deck and pilot house, as well as to rehabilitate the rear of building. The property is located mid-block and the back of building is not visible from the public right-of-way. Although a fire lane runs behind property, it is a private, locked alley for residents only. SCOPE OF WORK • Construct pilot house and roof deck. • Extend chimney height. • Re-clad rear double bay window at the back wall on rear ell. • Create new window openings on rear ell. • Close select window openings and infill with brick. • Create new door opening from existing window on rear wall of main block. Construct stairs from new doorway to back breezeway. • Replace windows and door. • No work to front façade. STANDARDS FOR REVIEW: The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties and Guidelines include: • Standard 2: The historic character of a property will be retained and preserved. The removal of distinctive materials or alterations of features spaces and spatial relationships that characterize a property will be avoided. -

Grade 5 – the Birchbark House Companion Resources for the ELA Guidebooks for Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities

Grade 5 – The Birchbark House Companion Resources for the ELA Guidebooks for Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities This past year, the Department created the Companion Resources for the ELA Guidebooks for Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities to facilitate access and opportunity with a high-quality curriculum, improve professional learning between content area specialists and expert teachers of special education teachers, and increase options for students with the most complex needs to participate in an inclusive and least restrictive environment. The Companion Resources are available for the 2020-2021 academic year in DRAFT form. For teachers/ schools/ systems choosing to use these Companion Resources, the Department requires you to complete a survey so that we may track implementation and solicit your feedback along the way. Thus, if you have not already, please complete the survey found at the link below. The Companion Resources are now available in DRAFT form for teachers, schools, and systems to pilot during the 2020-2021 academic year. Please complete the brief survey linked below so that the Department can track implementation and solicit feedback in order to improve the quality of the Companion Resources. Happy piloting! *** We are also including related links to support your introduction to and use of the Companion Resources: Survey to Access the Draft Companion Resources Training: Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: Companion Resources for the ELA Guidebooks, Teacher Leader Summit 2020 Guidance -

Explaining Changes in House Prices1

Gregory D Sutton +41 61 280 8421 [email protected] Explaining changes in house prices1 Against the backdrop of sharply lower global equity prices, an important question facing policymakers is the outlook for consumer spending.2 The exact relationship between changes in household wealth and consumer spending is uncertain. Even so, the recent large declines in equity prices are likely to be a depressing influence on consumer spending in the future. Offsetting this effect is the strong recent growth in house prices in a number of countries. Academic research has documented an important influence of housing wealth on consumer behaviour.3 The outlook for consumer spending, therefore, also depends on the future course of house prices. Presumably, a continuation of the global economic slowdown would slow the growth in house prices. Yet, house prices could also come under pressure even in the absence of a further slowdown in economic activity if stock market wealth is an important determinant of the demand for housing. This special feature examines the extent to which house price fluctuations in six advanced economies – the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Ireland, the Netherlands and Australia – can be attributed to fluctuations in national incomes, interest rates and stock prices. To this end, the joint behaviour of house prices, national incomes, real interest rates and stock prices is studied within the context of a simple empirical model. The empirical framework permits one to identify the typical response of house prices to changes in a small set of key determinants and also to examine the extent to which house prices have tended to deviate from the values predicted by them. -

March 12, 2021

Tax News & Views Capitol Hill briefing. March 12, 2021 In this issue: Biden signs American Rescue Plan into law ............................................................................................................ 1 Taxwriters preview ‘Build Back Better’ debate at Ways and Means subcommittee hearing ................................. 3 Neal, Pascrell push for extended 2021 tax filing season ......................................................................................... 5 Biden to nominate Batchelder, Davidson for Treasury posts ................................................................................. 7 Deloitte Tax looks at COVID-related changes affecting compensation and benefits, Qualified Opportunity Funds ............................................................................................................................. 8 Biden signs American Rescue Plan into law President Biden on March 11 signed the American Rescue Plan into law, capping an eight-week sprint by congressional Democrats and the White House to enact the sweeping $1.9 trillion tax-and-spending package aimed at addressing the continuing economic and health impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. URL: https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR1319EAS.pdf Tax News & Views Page 1 of 10 Copyright © 2021 Deloitte Development LLC March 12, 2021 All rights reserved. The new law, among other things, extends and enhances a number of current-law tax incentives for businesses, provides another round of direct economic -

Indoor and Outdoor Noise Changes Due to the COVID-19 Lockdown and Their Effects on Individuals' Expectations and Preferences

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Indoor and outdoor noise changes due to the COVID‑19 lockdown and their efects on individuals’ expectations and preferences Marco Caniato1*, Federica Bettarello2 & Andrea Gasparella1 The COVID‑19 pandemic signifcantly modifed our urban territories. One of the most strongly afected parameters was outdoor noise, caused by trafc and human activity in general, all of which were forced to stop during the spring of 2020. This caused an indubitable noise reduction both inside and outside the home. This study investigates how people reacted to this new unexpected, unwanted and unpredictable situation. Using feld measurements, it was possible to demonstrate how the outdoor sound pressure level clearly decreased. Furthermore, by means of an international survey, it was discovered that people had positive reaction to the lower noise level. This preference was generally not related to home typology or location in the city, but rather to a generalized wish to live in a quieter urban environment. During the COVID-19 emergency many diferent human activities have been strongly modifed or banned. Te pandemic has made many people around the world stay at home at some point in time, strongly limiting actions and unfortunately personal freedom. Tese restrictions have been necessary to save lives. Tere have been many consequences of this: (1) economic crisis, (2) a stop to working activities and/or smart working from home, (3) imposed distances and (4) strong reduction in trafc and normal activities. As an example, in Italy the trafc decreased by 79% during April 2020 compared to April 2019 1. Tis situation afected the outdoor environment 2,3 in terms of pollutant emissions; one of these is noise4–6. -

Scene on Radio More Democracy (Season 4, Episode 12) Transcript

Scene On Radio More Democracy (Season 4, Episode 12) Transcript http://www.sceneonradio.org/s4-e12-more-democracy/ John Biewen: A content warning. This episode includes the sound of police brutality that a lot of people will find hard to listen to. [Sound: chants of "No Justice, No Peace" at a rally.] Chenj, we are not a news podcast. Chenjerai Kumanyika: No, we're not. John Biewen: We very consciously take a longer view. You know. We try to get at truths about who and what we are as a society that are more evergreen. Uh, but man. Chenjerai Kumanyika: Whew. So this is a series about democracy in America, right? And we posted the first episode as Trump's impeachment trial was getting started. And now here we are in June 2020, we're recording the last episode of our season. And there's a major protest movement. I mean, you could even say a rebellion happening across the country. John Biewen: We asked at the beginning of season four: hasn't American democracy always been in crisis? And I think our series has shown the answer is yes, but it's sort of like with medical conditions, right? There are chronic crises and acute crises. And right now we've got several immediate emergencies, any one of them historic, layered on top of each other. Chenjerai Kumanyika: And I think the police are a really good example of that, right? You know, policing is an institution that has been involved in racist violence from its inception. But the acute problem is the latest murder of an unarmed Black man by a white police officer, George Floyd in Minneapolis. -

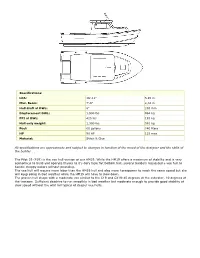

Pilot 19 (P19) Is the Vee Hull Version of Our HM19

Specifications: LOA: 18'-11" 5,85 m Max. Beam: 7'-8" 2,34 m Hull draft at DWL: 8" 203 mm Displacement DWL: 1,900 lbs 864 kg PPI at DWL: 425 lbs 193 kg Hull only weight: 1,300 lbs. 591 kg Fuel: 60 gallons 240 liters HP 90 HP 125 max Material: Stitch & Glue All specifications are approximate and subject to changes in function of the mood of the designer and the skills of the builder . The Pilot 19 (P19) is the vee hull version of our HM19. While the HM19 offers a maximum of stability and is very economical to build and operate thanks to it's dory type flat bottom hull, several builders requested a vee hull to handle choppy waters without pounding. The vee hull will require more labor than the HM19 hull and also more horsepower to reach the same speed but she will keep going in bad weather while the HM19 will have to slow down. The proven hull shape with a moderate vee similar to the C19 and CX19:45 degrees at the cutwater, 10 degrees at the transom. Sufficient deadrise to run smoothly in bad weather but moderate enough to provide good stability at slow speed without the wild roll typical of deeper vee hulls. The generous freeboard and the classic sheer are also tried and true features contributing to seaworthiness. This boat will negotiate both head and following seas with ease. The P19 will require 90 HP to cruise in the low 30 mph range. This boats transom is designed for a standard 20" shaft. -

The Teen Years Explained: a Guide to Healthy Adolescent Development

T HE T EEN Y THE TEEN YEARS EARS EXPLAINED EXPLAINED A GUIDE TO THE TEEN YEARS EXPLAINED: HEALTHY A GUIDE TO HEALTHY ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT ADOLESCENT : By Clea McNeely, MA, DrPH and Jayne Blanchard ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT A GUIDE TO HEALTHY DEVELOPMENT The teen years are a time of opportunity, not turmoil. The Teen Years Explained: A Guide to Healthy Adolescent Development describes the normal physical, cognitive, emotional and social, sexual, identity formation, and spiritual changes that happen during adolescence and how adults can promote healthy development. Understanding these changes—developmentally, what is happening and why—can help both adults and teens enjoy the second decade of life. The Guide is an essential resource for all people who work with young people. © 2009 Center for Adolescent Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America. Printed and distributed by the Center for Adolescent Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Clea McNeely & Jayne Blanchard For additional information about the Guide and to order additional copies, please contact: Center for Adolescent Health Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health 615 N. Wolfe St., E-4543 Baltimore, MD 21205 www.jhsph.edu/adolescenthealth 410-614-3953 ISBN 978-0-615-30246-1 Designed by Denise Dalton of Zota Creative Group Clea McNeely, MA, DrPH and Jayne Blanchard THE TEEN YEARS EXPLAINED A GUIDE TO HEALTHY ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT Clea McNeely, MA, DrPH and Jayne Blanchard THE TEEN YEARS EXPLAINED A GUIDE TO HEALTHY ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT By Clea McNeely, MA, DrPH Jayne Blanchard With a foreword by Nicole Yohalem Karen Pittman iv THE TEEN YEARS EXPLAINED CONTENTS About the Center for Adolescent Health ........................................ -

Follow-Up on Family Practice Residents' Perspectives on Length and Content of Training

J Am Board Fam Pract: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.17.5.377 on 8 September 2004. Downloaded from Follow-up on Family Practice Residents’ Perspectives on Length and Content of Training Marguerite Duane, MD, MHA, Susan M. Dovey, PhD, Lisa S. Klein, and Larry A. Green, MD Background: The structure of family practice residency programs remains essentially unchanged from the model first proposed more than 35 years ago. Advances in medical technology and knowledge com- bined with increasing restrictions on resident work hours and decreasing medical student interest in- vite reconsideration of how family physicians are trained. Methods: We resurveyed 442 third-year family practice residents who had participated in a prior study in 2000 to determine whether their opinions about the length and content of residency had changed and whether they would still choose to be a physician and a family physician. Results: Thirty-seven percent of responding third-year residents favored extending family practice residency to 4 years. Compared as groups, there was relatively little change in opinion between first- and third-year residents. However, residents’ individual responses about the settings and content areas for which they would be willing to consider extending training varied considerably between years 1 and 3. Personal characteristics did not seem to influence residents’ opinions about length and content of training. Reasons for favoring a 4-year program and barriers to change were similar to those reported previously. Residents’ commitment to medicine and family medicine was still strong and was not associ- ated with their opinions about length of training. Conclusion: Although most surveyed residents favored a 3-year residency program, a substantial minority still supported extending training to 4 years, and the majority would still choose to enter fam- ily medicine programs if they were extended. -

Changes to the White House: 1830 – 1952

Classroom Resource Packet Changes to the White House: 1830 – 1952 INTRODUCTION When studying history, it is important to examine how things can change over time. How did we get from point A to point B? Also, why did we get from point A to point B? From the outside, the White House appears to rarely change. The Residence, along with the East and West Wings, stands as an enduring symbol of the presidency and the United States, but behind the recognizable façade many changes have taken place to enlarge and update the space to meet the evolving needs of the first families. Explore some of the changes, expansions, and renovations of the White House from the completion of the porticoes in 1830 to the last major renovation ending in 1952. CONTEXTUAL ESSAY President George Washington oversaw the initial design selection for the Executive Mansion and chose architect James Hoban’s plan in 1792. Over the next three decades, the White House would be completed, burned by the British, and rebuilt with porticoes, or porches, added to its southern and northern fronts (Images 1 & 2). The iconic central White House building was completed by 1830, and its exterior has largely remained the same. From the 1830s until 1902, alterations to the White House occurred principally to its interior. These changes not only reflected the evolving tastes and needs of its occupants, but also included the installation of new amenities such as running water, central heating, and electricity. Image 2 The President’s House was designed to be an office and a home. -

Planning Ahead for Your Transplant

1 Clinical Transplant Services Kidney/Pancreas Transplant Program OHSU Patient Label Mail Code: CB569 ● 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd. ● Portland, OR 97239-3098 Tel: 503/494-8500 ● Toll free: 800/452-1369 x 8500 ● Fax: 503/494-4492 **Please complete all pages and return to your Transplant Social Worker** Keep a copy for yourself as your plan will be reviewed while listed and at time of transplant PLANNING AHEAD FOR YOUR TRANSPLANT Being well prepared for a kidney transplant is a key part of your success. This form details the practical issues around transplantation and can help make this time less stressful. You will receive a packet titled “You and Your Kidney” at time of listing; review it every 2 months while waiting for your transplant; keep it always available and bring it with you when you are called in for transplant. It is essential to notify the Kidney Transplant Program of any changes with your plan listed below. NAME: DOB: When Called for Transplant When you are on the deceased donor waitlist, the call can come at any time so you need to be ready to leave the house within 1 hour. You will need to have made arrangements for your children, pets, work notification, paying bills, etc… If you are flying, you will need current airline schedules. If driving, you will need a working vehicle with fuel and may need to secure directions/map to OHSU. You must bring a copy of your medical insurance and prescription/drug coverage card(s) when you come in for transplant.