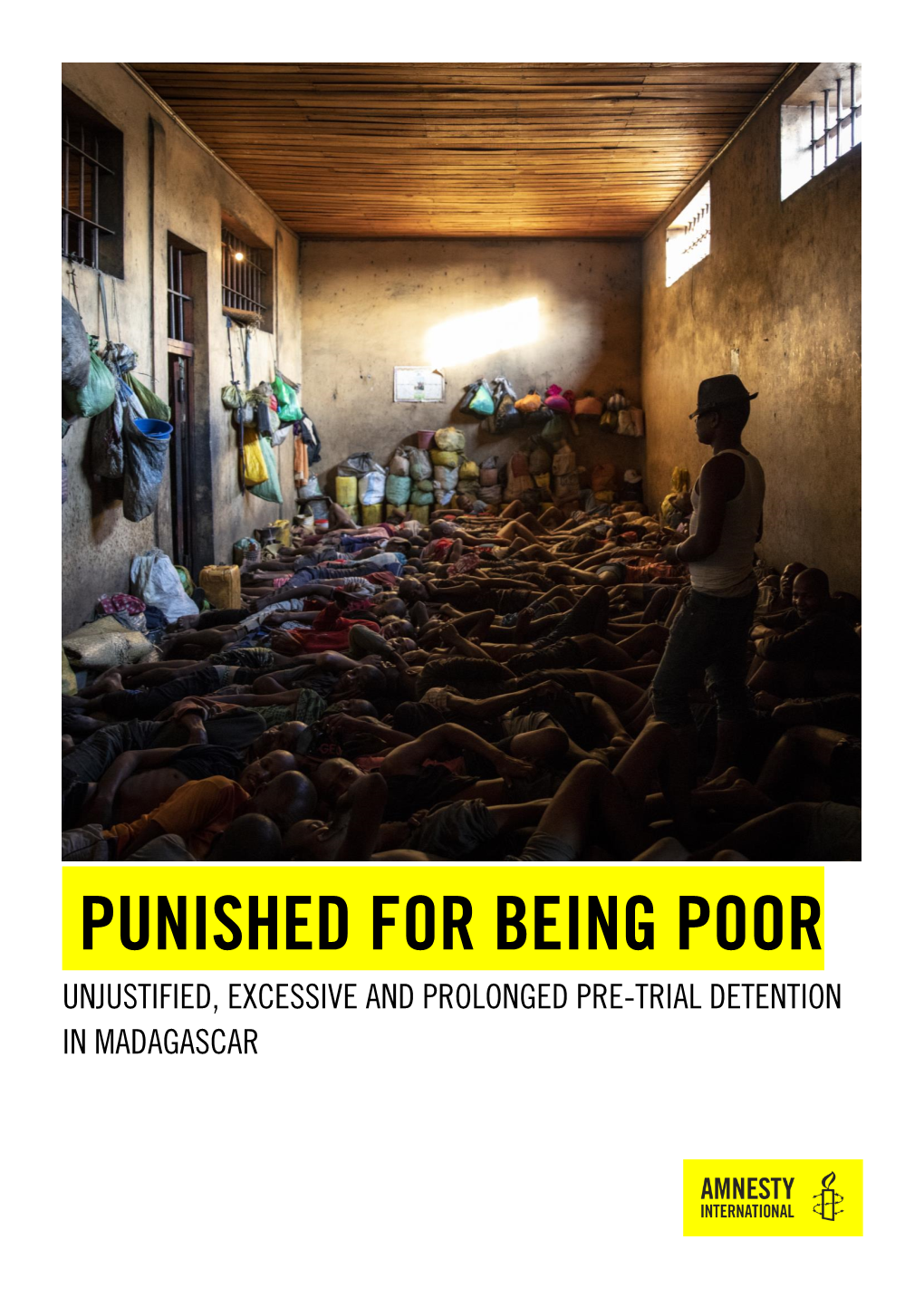

Punished for Being Poor Unjustified, Excessive and Prolonged Pre-Trial Detention in Madagascar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Needs, Accessibility and Utilization of Library Information Resources As Determinants of Psychological Well-Being of Prison Inmates in Nigeria

29 INFORMATION NEEDS, ACCESSIBILITY AND UTILIZATION OF LIBRARY INFORMATION RESOURCES AS DETERMINANTS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING OF PRISON INMATES IN NIGERIA Sunday Olanrewaju Popoola (1), Helen Uzoezi Emasealu (2) Department of Library, Archival and Information Studies & Senior Lecturer, University of Ibadan, Nigeria, drpo- [email protected] (1) Reference Librarian, University of Port Harcourt, Nigéria, [email protected] (2) Abstract information resources and psychological well-being of the inmates (r=0.665.p≤ 0.05). Also, there was significant rela- This paper investigated information needs, accessibility and tionship between: psychological well-being and accessibility utilization of library information resources as determinants of to library information resources by prison inmates (r=0.438; psychological well-being of prison inmates in Nigeria. Sur- p≤ 0.05); utilization of library information resources (r= vey research design of the correlation type was adopted. The .410; p≤05), and information needs (r=.454; p≤ 05). Result stratified random sampling was used to select 2875 inmates also indicated that information needs, accessibility to library from the population of 4,823 in 12 prisons with functional information resources and utilization of library information libraries. A questionnaire titled Information need, accessibil- resources are very critical ingredients in determining the ity, utilization and psychological well-being of Prison In- psychological well-being of prison inmates. Consequently, mates was used to collect data on the sampled 2875 inmates all stakeholders should endeavour to equip prison libraries out of which 2759 correctly completed questionnaire result- with relevant and current information resources for im- ing in a response rate of 95.34%, were used in data analysis. -

Prison Education in England and Wales. (2Nd Revised Edition)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 388 842 CE 070 238 AUTHOR Ripley, Paul TITLE Prison Education in England and Wales. (2nd Revised Edition). Mendip Papers MP 022. INSTITUTION Staff Coll., Bristol (England). PUB DATE 93 NOTE 30p. AVAILABLE FROMStaff College, Coombe Lodge, Blagdon, Bristol BS18 6RG, England, United Kingdom (2.50 British pounds). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Correctional Education; *Correctional Institutions; Correctional Rehabilitation; Criminals; *Educational History; Foreign Countries; Postsecondary Education; Prisoners; Prison Libraries; Rehabilitation Programs; Secondary Education; Vocational Rehabilitation IDENTIFIERS *England; *Wales ABSTRACT In response to prison disturbances in England and Wales in the late 1980s, the education program for prisoners was improved and more prisoners were given access to educational services. Although education is a relatively new phenomenon in the English and Welsh penal system, by the 20th century, education had become an integral part of prison life. It served partly as a control mechanism and partly for more altruistic needs. Until 1993 the management and delivery of education and training in prisons was carried out by local education authority staff. Since that time, the education responsibility has been contracted out to organizations such as the Staff College, other universities, and private training organizations. Various policy implications were resolved in order to allow these organizations to provide prison education. Today, prison education programs are probably the most comprehensive of any found in the country. They may range from literacy education to postgraduate study, with students ranging in age from 15 to over 65. The curriculum focuses on social and life skills. -

Problems of National Public and Private Law

ISSN 2336‐5439 EUROPEAN POLITICAL AND LAW DISCOURSE • Volume 3 Issue 4 2016 PROBLEMS OF NATIONAL PUBLIC AND PRIVATE LAW Dmytro Yagunov, MSSc in Criminal Justice National expert of the Project of the Council of Europe «Further Support for the Penitentiary Reform in Ukraine» PRISON REFORM IN UKRAINE: SOME ANALYTICAL NOTES AND RECOMMENDATIONS On 18 May, 2016, the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine abolished the State Penitentiary Service of Ukraine (the SPS) as a central executive body. The Government decided: 1) to abolish the State Penitentiary Service and put all tasks and functions of state prison and probation policy on the Ministry of Justice; 2) to provide that the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine would be the successor of the State Penitentiary Service of Ukraine in sphere of the public prison and probation policy. The reform had led to radical and sometimes unexpected changes in the public administration of the penitentiary system of Ukraine. The question is whether these changes would leas to positive results. The prison reform of February ‐ May 2016 (taken as a whole, and on the example of certain areas) has more than sufficient reasons to be evaluated critically, and sometimes extremely critically. This paper is focused on research of different directions of the prison reform announced by the Ministry of Justice in 2016. Key words: prison system, probation service, prison and probation reform, public administration of the penitentiary system of Ukraine, Ministry of Justice of Ukraine, State Penitentiary Service of Ukraine, prison privatization, juvenile probation centers, recommendations for reform. Introduction At the end of 2015, the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine has declared 2016 as the Year of the prison reform. -

WOIPFG's Investigative Report on the Falun Dafa Practitioners' Coerced

追查迫害法轮功国际组织 World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong To investigate the criminal conduct of all institutions, organizations, and individuals involved in the persecution of Falun Gong; to bring such investigation, no matter how long it takes, no matter how far and deep we have to search, to full closure; to exercise fundamental principles of humanity; and to restore and uphold justice in society WOIPFG’s Investigative Report on the Falun Dafa Practitioners’ Coerced Production of Forced Labor Products in the Chinese Communist Party’s Prisons and Labor Camps April 3, 2018 Table of Contents Forword Ⅰ. Slave Labor Production in Mainland China: Forms and Scale. (I) Prisons with Slave Labor Production in the Name of an Enterprise (II) Prisons, labor camps and detention centers that produces slave labor products and the companies that commission their services 1. Slave labor products produced in prisons and the companies that commission them 1.1 Hangzhou Z-shine industrial Co., Ltd. relies on 38 prisons for production 1.2 Zhejiang Province No. 1, No. 4, No. 5 and No. 7 Prisons and Quzhou Haolong Clothing Co., Ltd 1.3 Jiamusi Prison and Zhejiang Goodbrother Shoes Co., Ltd 1.4 Liaoning Province Women’s Prison and related companies 1.5 Shanghai Women’s Prison and related companies 1.6 Heilongjiang Tailai Prison and South Korean brand MISSHA 1.7 Shanghai prisons, Shanghai forced labor camps and related companies 1.8 Collaboration between Shanghai Tilanqiao Prison and Shanghai Soap Co., Ltd., Shanghai Jahwa Corporation 2. Slave Labor Products Made in Forced Labor Camps and the Companies that Commissioned them 2.1 Hebei Province Women’s Labor Camp and Related Companies 2.1.1 Hebei Yikang Cotton Textile Co. -

Small Hydro Resource Mapping in Madagascar

Public Disclosure Authorized Small Hydro Resource Mapping in Madagascar INCEPTION REPORT [ENGLISH VERSION] August 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared by SHER Ingénieurs-Conseils s.a. in association with Mhylab, under contract to The World Bank. It is one of several outputs from the small hydro Renewable Energy Resource Mapping and Geospatial Planning [Project ID: P145350]. This activity is funded and supported by the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP), a multi-donor trust fund administered by The World Bank, under a global initiative on Renewable Energy Resource Mapping. Further details on the initiative can be obtained from the ESMAP website. This document is an interim output from the above-mentioned project. Users are strongly advised to exercise caution when utilizing the information and data contained, as this has not been subject to full peer review. The final, validated, peer reviewed output from this project will be a Madagascar Small Hydro Atlas, which will be published once the project is completed. Copyright © 2014 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK Washington DC 20433 Telephone: +1-202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the consultants listed, and not of World Bank staff. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work and accept no responsibility for any consequence of their use. -

RAPPORT D'activité 2015-2016 Projet D'adaptation De La Gestion Des Zones Côtières Au Changement Climatique

17' 0( (/ 1( ¶( 1 & 2 2 5 / , 2 9 * 1 , ( ( ¶ / ( 7 ( ' ' ( ( 6 5 ) ( 2 7 6 5 , ( 1 , 7 6 0 MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT, DE L’ECOLOGIE ET DES FORETS SECRETARIAT GENERAL BUREAU NATIONAL DE COORDINATION DES CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES RAPPORT D'ACTIVITÉ 2015-2016 Projet d'Adaptation de la gestion des zones côtières au changement climatique PROJET D’AdaptatioN DE LA GESTION DES ZONES CÔTIÈRES AU CHANGEMENT CLIMatiQUE Etant un pays insulaire, Madagascar est Plusieurs actions ont été entreprises par le considéré comme l’un des pays les plus projet d’Adaptation de la gestion des Zones SOMMAIRE vulnérables à la variabilité et aux changements Côtières au changement climatique en tenant climatiques. Les dits changements se compte de l’Amélioration des écosystèmes CONTEXTE 5 manifestent surtout par le «chamboulement et des moyens de subsistance » au cours du régime des pluviométries, l’augmentation de l’année 2016 comme la réalisation des COMPOSANTE 1 : RENForcement DES capacITÉS de la température, la montée du niveau de études de vulnérabilité dans les quatre zones INSTITUTIONNELLES AUX Impacts DU CHANGEMENT la mer et l’intensification des évènements d’intervention, la création d’un mécanisme de CLImatIQUE DANS LES SITES DU proJET climatiques extrêmes tels que les cyclones, les coordination et la mise en place de la Gestion (MENABE, BOENY, VatovavY FItovINANY ET ATSINANANA) 7 inondations et les sècheresses. Devant cette Intégrée des zones côtières dans les régions situation alarmante, des actions d’adaptation Atsinanana, Boeny, et Vatovavy Fitovinany, ainsi COMPOSANTE 2 : RÉHABILItatION ET GESTION DES ZONES sont déja mises en oeuvre à Madagascar afin de que la mise en œuvre des scénarios climatiques CÔTIÈRES EN VUE d’uNE RÉSILIENCE À LONG TERME 17 renforcer la résilience de la population locale et à l’échelle réduite de ces quatre régions. -

UNIVERSITE D'antananarivo Présenté Par : RAHAJASON Prosper

UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO DOMAINE DES ARTS, LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES MENTION: GEOGRAPHIE Parcours 4 : Environnement et Aménagement du Territoire LES ENJEUX DE L’AMENAGEMENT PERIURBAIN DANS LA COMMUNE RURALE DE BEMASOANDRO ITAOSY, District ANTANANARIVO ATSIMONDRANO, Région ANALAMANGA Mémoire pour l’obtention du diplôme de Master Présenté par : RAHAJASON Prosper Sous la direction de M. ANDRIAMITANTSOA Tolojanahary Maître de conférences 9 Février 2019 UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO DOMAINE DES ARTS, LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES MENTION: GEOGRAPHIE Parcours P4 : Environnement et Aménagement du Territoire LES ENJEUX DE L’AMENAGEMENT PERIURBAIN DANS LA COMMUNE RURALE DE BEMASOANDRO ITAOSY, District ANTANANARIVO ATSIMONDRANO, Région ANALAMANGA Mémoire pour l’obtention du diplôme de Master Présenté par RAHAJASON Prosper Sous la direction de M.ANDRIAMITANTSOA Tolojanahary Maître de conférences Membres du jury : - Président : M. RAVALISON James, Professeur ; - Rapporteur : M. ANDRIAMITANTSOA Tolojanahary, Maître de conférences - Juge : M. ANDRIAMIHAMINA Mparany, Maître de conférences Année Universitaire : 2017 - 2018 REMERCIEMENTS D’abord, je remercie Dieu de m’avoir aidé dans la réalisation de ce travail car sans lui je n’aurais pas eu la force et le courage d’y arriver. Ensuite, je remercie Monsieur Tolojanahary ANDRIAMITANTSOA, Maître de Conférences au sein de la mention Géographie, Directeur de l’Observatoire de l’Aménagement du Territoire et du Foncier, qui a accepté d’être mon Directeur de Recherche. En plus, ses directives m’étaient vraiment -

1 COAG No. 72068718CA00001

COAG No. 72068718CA00001 1 TABLE OF CONTENT I- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 6 II- INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 III- MAIN ACHIEVEMENTS DURING QUARTER 1 ........................................................................................................... 10 III.1. IR 1: Enhanced coordination among the public, nonprofit, and commercial sectors for reliable supply and distribution of quality health products ........................................................................................................................... 10 III.2. IR2: Strengthened capacity of the GOM to sustainably provide quality health products to the Malagasy people 15 III.3. IR 3: Expanded engagement of the commercial health sector to serve new health product markets, according to health needs and consumer demand ........................................................................................................ 36 III.4. IR 4: Improved sustainability of social marketing to deliver affordable, accessible health products to the Malagasy people ............................................................................................................................................................. 48 III.5. IR5: Increased demand for and use of health products among the Malagasy people -

Table Des Matières

UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO FACULTE DE DROIT, D’ECONOMIE, DE GESTION ET DE SOCIOLOGIE DEPARTEMENT DE SOCIOLOGIE ……………………. MEMOIRE DE MAITRISE (Cas de la Commune Rurale de Tsiafahy, District d’Antsimondrano) Présentée par : RAZANAKOLONA Tahiriniaina Minosoa Juge : RAMANDIMBIARISON Jean Claude, Professeur titulaire émérite Rapporteur : RAHERIMALALA Stephano, Maitres de conférences Encadreur : Madame RAMANDIMBIARISON Noëline, Professeur titulaire ANNEE UNIVERSITAIRE : 2014-2015 Date de soutenance : 25 Février 2015 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION PARTIE I : Etat des lieux et cadres théoriques Chapitre 1 : Situation historique et géographique de la Commune Chapitre 2 : Aperçus théoriques sur les méthodes d’investigation PARTIE II : Les activités socio-économiques de la population, bilan du diagnostic participatif et les problèmes principaux Chapitre 3 : Les activités socio-économiques de la population Chapitre 4 : Bilan du diagnostic participatif et problèmes principaux PARTIE III : Analyse et perspective d’avenir Chapitre 5 : Dynamiques sociales Chapitre 6 : Perspectives d’avenirs et recommandations CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHIE TABLES DES MATIERES LISTE DES TABLEAUX LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ANNEXES REMERCIEMENTS Ce mémoire n’aurait pu se concevoir sans l’aide de Dieu. En premier lieu, je rends grâce au Seigneur Tout puissant qui m’a donné la force pour la réalisation de ce travail. Ensuite, sans la collaboration des personnes suivantes, auxquelles je tiens à adresser ma profonde reconnaissance, je serai incapable de le mener à terme. Ainsi : Je remercie, Madame RAMANDIMBIARISON Noëline de nous avoir encadré pendant le déroulement de notre travail Je remercie aussi Monsieur le Maire de la commune Tsiafahy, RANDRIAMAHEFA Justin et ses collaborateurs qui ont accepté aux enquêtes et qui nous ont fournis les informations nécessaires pour notre travail. -

Family Information Packet

MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES ADMINISTRATION FAMILY INFORMATION PACKET CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES ADMINISTRATION FAMILY INFORMATION PACKET TABLE OF CONTENTS Department Mission…………………………………………………………………………….2 CRIME VICTIMS’ RIGHTS INFORMATION .................................................................................. 2 DISCIPLINE - Prisoner Discipline .................................................................................... 3 ELECTRONIC MESSAGES - Sending Emails to Prisoners via JPAY ......................... .10 FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT (FOIA) ................................................................ 10 GRIEVANCES - Prisoner/Parolee Grievance Process .................................................. 11 HEALTH CARE - The Rights of Prisoners to Physical and Mental Health Care ........... 13 EDUCATION ………………………………………………………………………………….16 JPAY .............................................................................................................................. 17 MAIL – Sending Mail to a Prisoner ................................................................................ 17 MARRIAGE – Marrying a Prisoner ................................................................................ 18 MONEY - Sending Money to a Prisoner via GTL ........................................................... 19 OFFENDER TRACKING INFORMATION SYSTEM (OTIS) .........................................20 ORIENTATION FOR PRISONERS .............................................................................. -

The State of Lemur Conservation in South-Eastern Madagascar

Oryx Vol 39 No 2 April 2005 The state of lemur conservation in south-eastern Madagascar: population and habitat assessments for diurnal and cathemeral lemurs using surveys, satellite imagery and GIS Mitchell T. Irwin, Steig E. Johnson and Patricia C. Wright Abstract The unique primates of south-eastern information system, and censuses are used to establish Madagascar face threats from growing human popula- range boundaries and develop estimates of population tions. The country’s extant primates already represent density and size. These assessments are used to identify only a subset of the taxonomic and ecological diversity regions and taxa at risk, and will be a useful baseline existing a few thousand years ago. To prevent further for future monitoring of habitat and populations. Precise losses remaining taxa must be subjected to effective estimates are impossible for patchily-distributed taxa monitoring programmes that directly inform conserva- (especially Hapalemur aureus, H. simus and Varecia tion efforts. We offer a necessary first step: revision of variegata variegata); these taxa require more sophisticated geographic ranges and quantification of habitat area modelling. and population size for diurnal and cathemeral (active during both day and night) lemurs. Recent satellite Keywords Conservation status, geographic range, GIS, images are used to develop a forest cover geographical lemurs, Madagascar, population densities, primates. Introduction diseases (Burney, 1999). However, once this ecoregion was inhabited, its combination of abundant timber and The island nation of Madagascar has recently been nutrient-poor soil (causing a low agricultural tenure classified as both a megadiversity country and one of time) led to rapid deforestation. 25 biodiversity hotspots, a classification reserved for Green & Sussman (1990) used satellite images from regions combining high biodiversity with high levels 1973 and 1985 and vegetation maps from 1950 to recon- of habitat loss and extinction risk (Myers et al., 2000). -

China – CHN37989 – Laogai – Laojiao – Re-Education Through Labor

Country Advice China China – CHN37989 – Laogai – Laojiao – Re-education through labor – Black jails – Christians 12 January 2011 1. Please advise whether reports indicate that “compulsory re-education classes” or local “brainwashing” classes were utilised by the authorities in Fujian or China more broadly during the period 1988 – 2007 and whether there are any descriptions of such classes being run at schools, in particular as may apply to their discouragement of the Christian faith? The Laogai Research Foundation provides comprehensive information on China‟s system of labour camps. It provides the following definitions: Laogai is „reform through labour‟ and laojiao is „reeducation through labour‟. According to its latest report, covering the period 2007 – 2008 laojiao „reeducation through labor‟ is a component of the Laogai system. The laojiao „reeducation through labor‟ allows for the arrest and detention of petty criminals for up to three years without formal charge of trial, and this system is not considered by the Chinese government to qualify as a prison.1 The entire Laogai system is composed of approximately one thousand camps. The legislative framework for the institution of the Laogai was established in 1954 as part of the “Regulations on Reform through Labor”.2 The Handbook states that because of the closed and secret nature of the Laogai system, it is impossible to provide a precise and accurate record of the exact number of laogai camps and the number of inmates who are detained therein. The Chinese government authorities consider that data pertaining to the laogai system are state secrets and for this reason do not allow outside entities to access these camps.