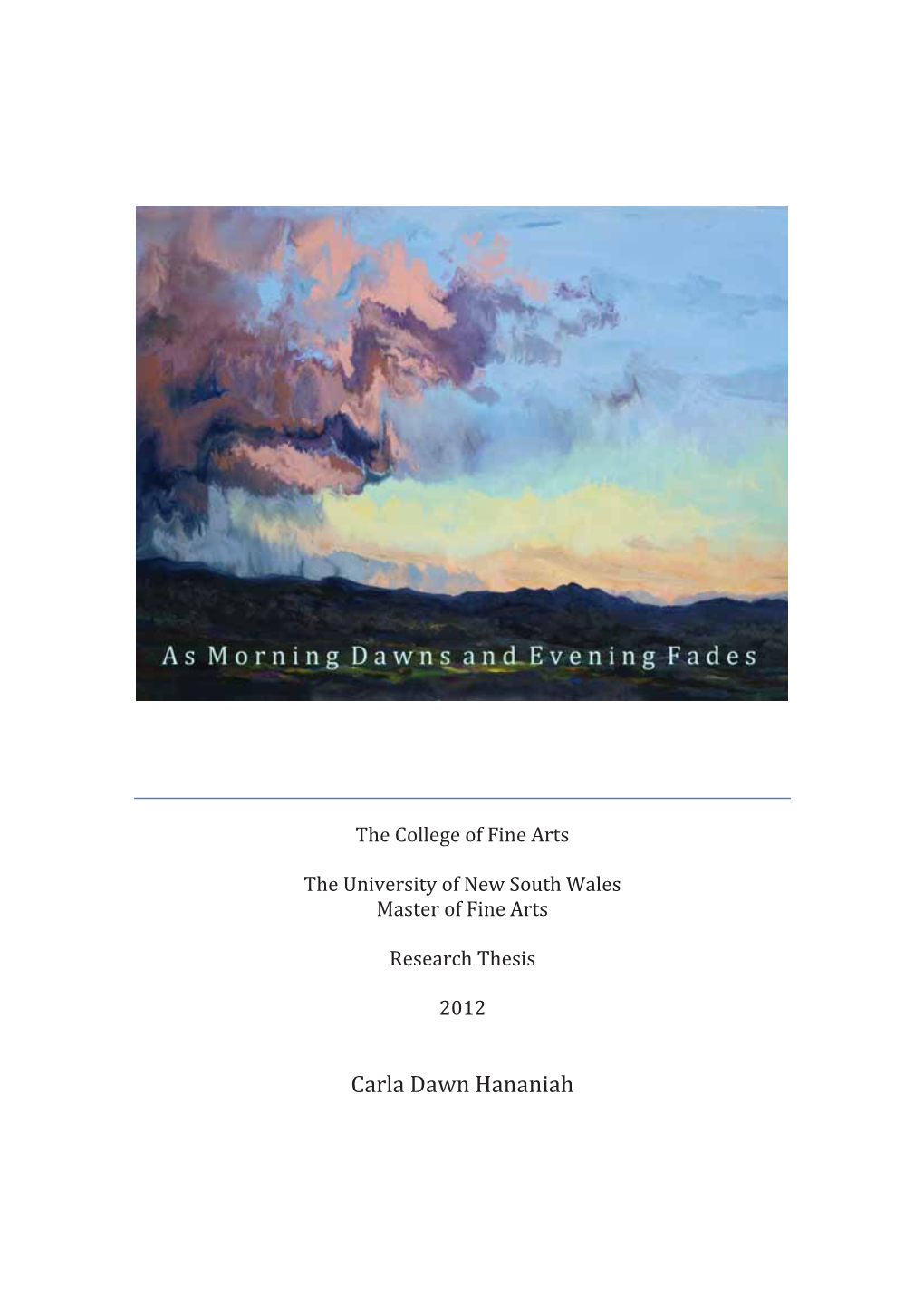

Carla Dawn Hananiah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tauranga Art Gallery Trust Our Year in Review 2014 – 15 2 |

Tauranga Art Gallery Trust Our Year in Review 2014 – 15 2 | Cover: Matthew Smith (Australia), Sailing by. Photo: Natural History Museum, London Tauranga Art Gallery Trust Our Year in Review 2014-15 | 1 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Highlights Contents 3.0 Governance 3.1 Chairperson report 4.0 Exhibitions 4.1 Touring with TAG 5.0 Education and Visitor Programmes 5.1 Education Programme 5.2 Public Programmes 6.0 Venue Hire & Events 7.0 Communications 8.0 Friends of the Gallery 9.0 Sponsors/Stakeholders 10.0 Staff 11.0 Financial Performance 12.0 Financial Statements and Audit Report 2 | 1.0 Introduction The principal activity of The Tauranga Art Gallery Trust (‘TAGT’ or ‘the Trust’) is to govern a public art gallery in Tauranga. The Tauranga Art Gallery (‘TAG’ or ‘the Gallery’) researches and presents exhibitions of historical, modern and contemporary art. This is the 17th Year in Review publication of the TAGT since its establishment in 1998. This report outlines the activities of the TAGT for the year ending 30 June 2015. Elizabeth Thomson, Invitation to Openness — Substantive and Transitive States (detail). Photo: Tauranga Art Gallery Tauranga Art Gallery Trust Our Year in Review 2014 – 15 | 3 2.0 Highlights 3.0 Governance 66,270 visitors The Trustees as at 30 June 2014 were: Peter Anderson (Chairperson) MCR, IMD, Laussane Sonya Korohina B.A. Grad. Dip in Arts 23 exhibitions Management. Judith Stanway M Soc Sci, BBS, FCA, AF Inst D. 4 exhibitions Mary Stewart Grad Dip Mgt. touring Mary Hackett Dip Bus Studies, RGON. simultaneously Deborah Meldrum BA (Hons), Dip Tchg. -

Landscape Painting

Landscape Painting Kate Sandilands Joyce Nelson, Sign Crimes/Road Kill: From Mediascape to Landscape (Toronto, Between the Lines 1992). Andrew Wilson, The Culture of Nature: North American Landscape from Disney to the Exxon Valdez (Toronto, Between the Lines 1991). As Raymond Williams wrote some time ago, "the idea of nature contains, though often unnoticed, an extraordinary amount of human history."'At the same time as the idea marks a series of radically different, and historically changing, usages, relations and meanings, it has also come to represent some basic quality, some underlying continuity that differentiates the epiphenomenal from the essential in humanity's vision of itself and the world. Thus, the movement between the "nature" of something and the something called "nature" shows a social order in the throes of self-definition: the tension between the production of an "essence," a sense of a historical trajectory, and the synchronic proliferation of plural meanings, in the working-out of "nature." Joyce Nelson and Andrew Wilson both capture this tension well; each shows the constitution of nature through the multiple, conflicting, and often destructive dis- courses of modernity and postrnodemity. Indeed, they both go a long way toward showing just how much human history is contained in the idea of "nature." In an era marked by "ecological crisis," such investigations would seem crucial indeed. But these books are not panic texts, not works of social inquiry parroting the voices of "hard" science on environmental apocalypse. They are, instead, works which show the tensions and contradictionsof North Americans's relations to "nature," something that all too many contemporary writings of an environmentalistvein overlook in their singular condemnation of the more destructive elements of western social life. -

Exhume the Grave— Mccubbin and Contemporary Art 14 August to 28 November 2021 Free Entry | Open Daily 10.00Am to 5.00Pm

Media contact Media Miranda Brown T: 0491 743 610 Release E: [email protected] Exhume the grave— McCubbin and contemporary art 14 August to 28 November 2021 Free entry | Open daily 10.00am to 5.00pm After extended periods of closure, The sentiments and emotive subjects Geelong Gallery opens Exhume the of these works have helped develop for grave—McCubbin and contemporary art them a popular visual literacy: they are on Saturday 14 August. The exhibition images that have impressed themselves includes works by contemporary powerfully on public consciousness over Australian artists in response to time. Frederick McCubbin’s enduringly popular narrative paintings set within Geelong Gallery Senior Curator and the Australian bush. exhibition curator, Lisa Sullivan, said ‘The artists in Exhume the grave— Exhume the grave provides a McCubbin and contemporary art provide contemporary counterpoint to Frederick a re-evaluation and reinterpretation of McCubbin—Whisperings in wattle key works in McCubbin’s oeuvre from boughs, an exhibition that celebrates a First Nations, immigrant, and feminist the Gallery’s first significant acquisition, perspective. More than a century after McCubbin’s A bush burial. McCubbin painted these works, our Jill Orr ideas of nationhood have evolved: Exhume the grave: Medium (detail) 1999 Whisperings in wattle boughs opens we understand the negative impacts C-type print Geelong Gallery on Saturday 4 September and is of colonialism, and we have a greater Purchased through the Victorian Public Galleries Trust, 1999 programmed in celebration of the understanding of the wide social © Jill Orr, Courtesy of the artist Gallery’s 125th anniversary. diversity of immigrant experience, of the Photographers: Bruce Parker and Joanne Haslam for Jill Orr wider capabilities and contributions of At the time of his death in December women, beyond the prescribed gender 1917, Frederick McCubbin was one of roles depicted in historical narratives, the best-known and most successful and of the significant environmental artists of his time. -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

The Hudson River School

Art, Artists and Nature: The Hudson River School The landscape paintings created by the 19 th century artist known as the Hudson River School celebrate the majestic beauty of the American wilderness. Students will learn about the elements of art, early 19 th century American culture, the creative process, environmental concerns and the connections to the birth of American literature. New York State Standards: Elementary, Intermediate, and Commencement The Visual Arts – Standards 1, 2, 3, 4 Social Studies – Standards 1, 3 ELA – Standards 1, 3, 4 BRIEF HISTORY By the mid-nineteenth century, the United States was no longer the vast, wild frontier it had been just one hundred years earlier. Cities and industries determined where the wilderness would remain, and a clear shift in feeling toward the American wilderness was increasingly ruled by a new found reverence and longing for the undisturbed land. At the same time, European influences - including the European Romantic Movement - continued to shape much of American thought, along with other influences that were distinctly and uniquely American. The traditions of American Indians and their relationship with nature became a recognizable part of this distinctly American Romanticism. American writers put words to this new romantic view of nature in their works, further influencing the evolution of American thought about the natural world. It found means of expression not only in literature, but in the visual arts as well. A focus on the beauty of the wilderness became the passion for many artists, the most notable came to be known as the Hudson River School Artists. The Hudson River School was a group of painters, who between 1820s and the late nineteenth century, established the first true tradition of landscape painting in the United States. -

Australian Life in Town and Country

^v AUSTRALIAN LIFE IN TOWN ® COUNTRY E.G. BULEY «^5e»'I c^>->a: AV TT'^ Digitized by tiie Internet Arciiive in 2007 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.arcliive.org/details/australianlifeinOObuleuoft OUR ASIATIC NEIGHBOURS Indian Life. By Herbert Compton Japanese Life, By George W. Knox Chinese Life. By E. Bard Philippine Life. By James A. Le Roy Australian Life. OUR ASIATIC NEIGHBOURS AUSTRALIAN LIFE IN TOWN AND COUNTRY HYDRAULIC MINING, THE WALLON BORE, MOREE DISTRICT. DEPTH 3695 FEET, FLOW 800,000 GALS., TEMP. 114° F. & fe AUSTRALIAN LIFE IN TOWN AND COUNTRY c2S a« By E. C. BULEY ILLUSTRATED G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON Zbe 'Knfclietbocltei: press 1905 Copyright, 1905 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS •Cbe "Rnlcftetbocftcr presa, Hew IPorft CONTENTS CHAPTER I PAGE Country and Cwmate i CHAPTER II Squatters and Stations 14 CHAPTER III Station Work 28 CHAPTER IV On a SeIvECTion 42 CHAPTER V The Never-Never IvAND 55 CHAPTER VI On the WaIvIvAby Track 69 CHAPTER VII In Time oe Drought 81 V vi Contents CHAPTER VIII PAGE Urban Austrawa 95 CHAPTER IX I^iFE IN THE Cities io8 CHAPTER X State Sociai,ism and the Labour Party . 122 CHAPTER XI Golden Australia 134 CHAPTER XII Farm and Factory 145 CHAPTER XIII The Australian Woman 157 CHAPTER XIV Home and Social Life 169 CHAPTER XV The Australian at Play 182 CHAPTER XVI The Aborigines 195 CHAPTER XVII A White Australia 208 Contents vii CHAPTER XVIII PAGE Education, Literature, and Art . 220 CHAPTER XIX Nationai, Life in Austrawa . .232 CHAPTER XX The Austrawan 245 CHAPTER XXI Industrial, Pioneers 258 CHAPTER XXII Australia's Destiny 270 Index 283 ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Hydrauwc Mining, tkb Wai,i.on Bore, Moree District, Depth 3695 Feet, Flow 800,000 GAI.S., Temp. -

1 the Alps, Richard Strauss's Alpine Symphony and Environmentalism

Note: This is an expanded version of an article appearing in the journal Green Letters (2011); it is intended for a literary rather than musical readership, and the punctuation and spellings are British. The Alps, Richard Strauss’s Alpine Symphony and Environmentalism By Brooks Toliver Introduction After love and death, nature may well be European music’s preferred theme; it figures significantly in troubadour cansos, pastoral madrigals and operas, tone poems, impressionistic preludes, and elsewhere. In light of this it is puzzling how seldom actual nature is invoked in musical discourse. Composers—Richard Strauss among them—have been known to seek out nature in the manner of landscape painters, but there is no similar tradition among the critics, who ground nature-music and their judgments of it not in nature but in other music and criticism. When confronted with the vivid imagery of Strauss’s Alpine Symphony (1915), contemporaries wrote primarily of the aesthetics of vivid imagery, relegating the images themselves to the level of anecdote. Musicologists are quite adept at exploring the relationship of works to cultural constructions of nature, but relatively few have brought real environments into the discussion of canonical music. There has as yet been no serious consideration of how the Alps might be critical to an appreciation of the Alpine Symphony, nor has anyone theorized what the consequences of the Alpine Symphony might be for the Alps. Surely it is worth asking whether it metaphorically embodies sustaining or destructive relationships to the environment it represents, if it respects or disrespects nonhuman nature, and if love of nature is contingent on a symbolic domination of it, to name just three questions. -

Hewitt Gallery of Art Catalogues: Psychogeography

psychogeographyartists’ responses to place [and displacement] in real and imagined spaces april 1 - may 1, 2019 gallery director’s statement Frederick Brosen Psychogeography explores artists’ responses to place [and displacement] in real and imagined spaces. From the psychic Ben paljor chatag to the specific, from recollection to recording, the works in this exhibit recreate the power of place in the human jeFF chien-hsing liao imagination. The nine artists in this group exhibition have traversed the dahlia elsayed globe, from the North Pole to Alexandria, Egypt, from Tibet to Italy, and from Flatbush to Central Park. Some travel in ellie ga the imaginative realms, others may never leave the studio. This exhibit takes inspiration from the notion of dérive or kellyanne hanrahan “drifting,” a word coined by French Marxist philosopher, Guy Debord, one of the founders of the Situationists International emily hass movement. Hallie Cohen | Director of the Hewitt Gallery of Art matthew jensen “One can travel this world and see nothing. To achieve sarah olson understanding it is necessary not to see many things, but to look hard at what you do see.” curated By hallie cohen - Giorgio Morandi aBout the artists Frederick Brosen’s exquisite, highly detailed watercolors capture the light, the architecture, and the aura of a New York City street or a Florentine strada, while Ben paljor chatag’s watercolors deal with “inner qualities” he discovered in Tibet before emigrating to the United States. Taiwanese-born jeFF chien-hsing liao’s large- scale black and white photographs of the iconic Central Park are based on the Chinese lunar calendar and call to mind the vertical format and multiple perspectives of traditional Chinese landscape painting. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

View of Maitland from the Riverbank (With Apologies to Jan Vermeer and View of Delft) Published June 2006 to Accompany the Exhibition

View of Maitland from the riverbank (with apologies to Jan Vermeer and View of Delft) published June 2006 to accompany the exhibition View of Maitland from the riverbank (with apologies to Jan Vermeer and View of Delft) 1 july - 20 august 2006 publisher maitland regional art gallery 230 high street maitland, nsw australia 2320 ISBN 0-9758369-2-7 paintings photographed by Michel Brouet © artists and maitland regional art gallery This catalogue is copyright apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act. 230 high tel email street (02) artgallery@ maitland 4934 maitland. maitland of nsw 2320 9859 nsw.gov.au city the arts po box fax web placing heart into maitland 220 (02) mrag 2005 - 2007 maitland 4933 .org nsw 2320 1657 .au View of Maitland from the riverbank (with apologies to Jan Vermeer and View of Delft) 1 july - 20 august 2006 maitland regional art gallery the artists archer suzanne fitzjames michael frost joe lohmann emma macleod euan martin claire mckenzie alexander pinson peter robba leo ryrie judith walker john r white judith Maitland Sixth City of the Arts 2005 - 2007 iew of Maitland from the riverbank (with apologies to Jan Vermeer and View of Delft) is an exhibition which has been developed at Maitland Regional Art Gallery for a Vvariety of reasons. Last year, in the James Gleeson retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, I came across Gleeson’s painting of Delft, with homage to Jan Vermeer. I had seen this painting earlier in a private collection, and felt that Gleeson had not only captured his vision of Delft but also created an amazingly surreal new image of Delft which was a unique painting in its own right and not merely an adjunct to another artist’s creation. -

Gender Down Under

Issue 2015 53 Gender Down Under Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 Editor About Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

Final Hannah Online Credits

Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits WRITTEN & PRESENTED BY HANNAH GADSBY ------ DIRECTED & CO-WRITTEN BY MATTHEW BATE ------------ PRODUCED BY REBECCA SUMMERTON ------ EDITOR DAVID SCARBOROUGH COMPOSER & MUSIC EDITOR BENJAMIN SPEED ------ ART HISTORY CONSULTANT LISA SLADE ------ 1 Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits ARTISTS LIAM BENSON DANIEL BOYD JULIE GOUGH ROSEMARY LAING SUE KNEEBONE BEN QUILTY LESLIE RICE JOAN ROSS JASON WING HEIDI YARDLEY RAYMOND ZADA INTERVIEWEES PROFESSOR CATHERINE SPECK LINDSAY MCDOUGALL ------ PRODUCTION MANAGER MATT VESELY PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS FELICE BURNS CORINNA MCLAINE CATE ELLIOTT RESEARCHERS CHERYL CRILLY ANGELA DAWES RESEARCHER ABC CLARE CREMIN COPYRIGHT MANAGEMENT DEBRA LIANG MATT VESELY CATE ELLIOTT ------ DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY NIMA NABILI RAD SHOOTING DIRECTOR DIMI POULIOTIS SOUND RECORDISTS DAREN CLARKE LEIGH KENYON TOBI ARMBRUSTER JOEL VALERIE DAVID SPRINGAN-O’ROURKE TEST SHOOT SOUND RECORDIST LACHLAN COLES GAFFER ROBERTTO KARAS GRIP HUGH FREYTAG ------ 2 Hannah Gadsby’s Oz – Full Series Credits TITLES, MOTION GRAPHICS & COLOURIST RAYNOR PETTGE DIALOGUE EDITOR/RE-RECORDING MIXER PETE BEST SOUND EDITORS EMMA BORTIGNON SCOTT ILLINGWORTH PUBLICITY STILLS JONATHAN VAN DER KNAPP ------ TOKEN ARTISTS MANAGING DIRECTOR KEVIN WHTYE ARTIST MANAGER ERIN ZAMAGNI TOKEN ARTISTS LEGAL & BUSINESS CAM ROGERS AFFAIRS MANAGER ------ ARTWORK SUPPLIED BY: Ann Mills Art Gallery New South Wales Art Gallery of Ballarat Art Gallery of New South Wales Art Gallery of South Australia Australian War Memorial, Canberra