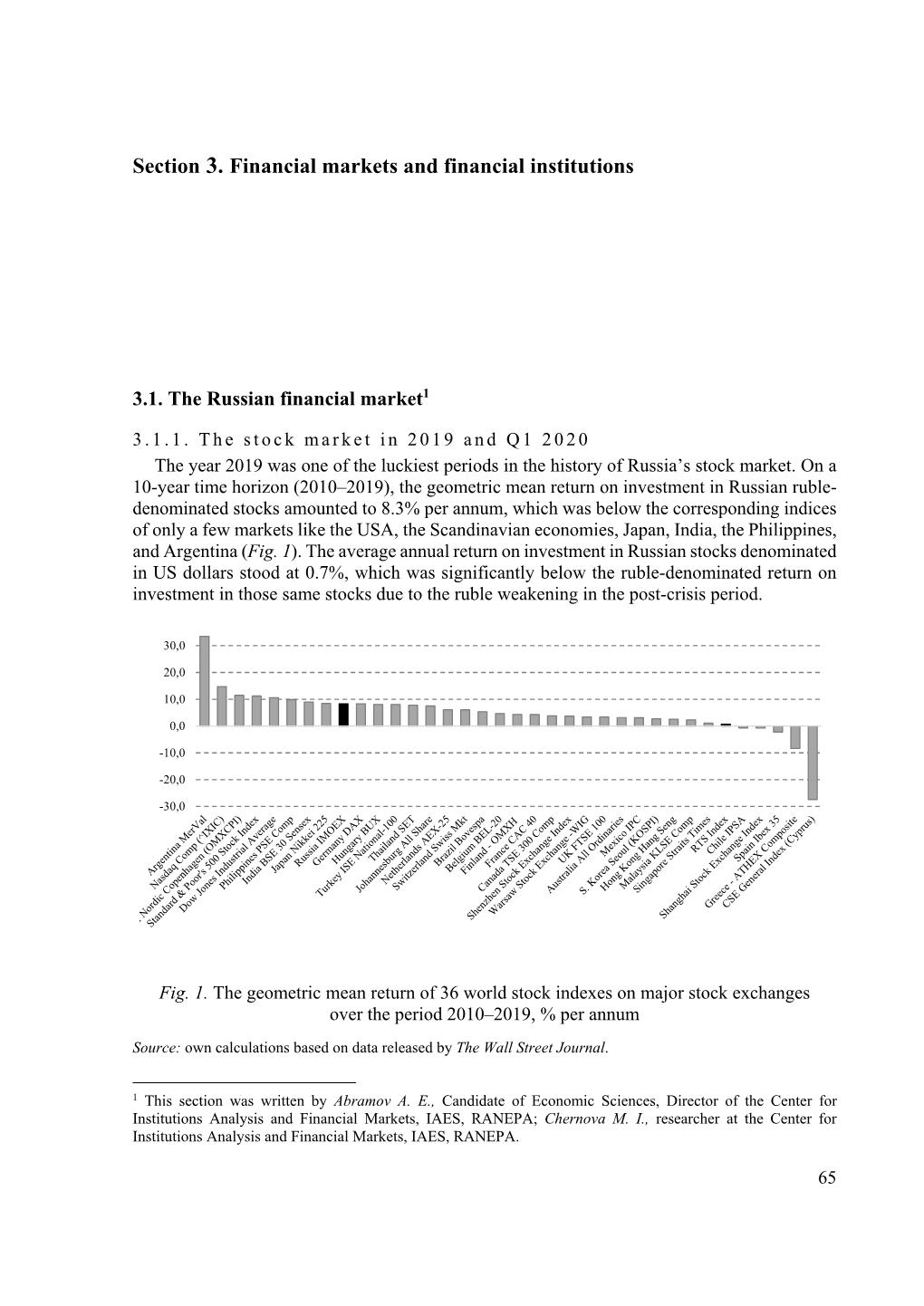

Section 3. Financial Markets and Financial Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

Outstanding Shares

PJSC RusHydro | Annual Report 2018 Share of securities in free float1 Shareholder agreements Date Free-float factor RusHydro’s shareholders can enter into Last trading day of 2016 0.23 shareholder agreements, including Last trading day of 2017 0.25 those that afford them an extent of Last trading day of 2018 0.19 control disproportionate to their contribution to the authorized capital2. Notifications on concluded shareholder agreements received by RusHydro Parties to the shareholder agreement Date of the shareholder agreement ↗ The Russian Federation as represented by the Federal Agency for State Property Management March 7, 2017 ↗ VTB Bank (PJSC) ↗ The Russian Federation as represented by the Federal Agency for State Property Management June 23, 2016 ↗ RusHydro’s subsidiaries: Hydroinvest3, EZOP, Energy Index – HydroOGK Outstanding shares Moscow Exchange listing Index inclusion: ↗ FTSE All-World Index AWORLDS; ↗ MOEX Russia Index (previous name – ↗ FTSE4Good Emerging; The Company’s shares have been MICEX Index) IMOEX; ↗ NASDAQ Russia NQRU; traded on the Moscow Exchange ↗ Electric Utilities Index MOEXEU; ↗ Nasdaq AlphaDEX Emerging Markets (formerly MICEX Stock Exchange). ↗ Broad Market Index MOEXBMI; NQDXEM; since February 4, 2008 (ticker: HYDR). ↗ State-Owned Companies Index ↗ STOXX Russia Total Market TCRUP; The securities are listed in Level 1, MOEXSCI; ↗ STOXX Optimized Russia EEORGT. the Exchange’s top quotation list. ↗ FTSE Emerging Index AWALLE; Moscow Exchange trading information Item 2016 2017 2018 Trading mode T+: stocks and DRs T+: stocks and DRs T+: stocks and DRs Currency RUB RUB RUB Maximum trade price 0.994 1.100 0.810 Minimum trade price 0.575 0.717 0.476 Year-end trade price 0.926 0.729 0.486 Trading volume, bn pcs 134 173 136 1 In accordance with the Moscow Exchange’s methodology for calculating the free-float factor published at http://www.moex.com/ru/index/MICEXINDEXCF/constituents/. -

Fundamental Factors Affecting the MOEX Russia Index: Retrospective Analysis1

Fundamental Factors Affecting the MOEX Russia Index: Retrospective Analysis1 Agata Lozinskaia1[0000-0001-8723-275X] and Anastasiia Saltykova2[0000-0002-4147-6350] 1 National Research University Higher School of Economics, Perm, Russia 2 National Research University Higher School of Economics, Perm, Russia [email protected] Abstract. This paper is an empirical study of the changing nature of the de- pendence of fundamental factors on the stock market index, which is the trend identified earlier in the Russian stock market. We empirically test the impact of daily values of fundamental factors on the MOEX Russia Index from 2003 to 2018. The analysis of the ARIMA-GARCH (1,1) model with a rolling window reveals that the change in the power and direction of the influence of the fun- damental factors on the Russian stock market persists. The Quandt-Andrews breakpoint test and Bai-Perron test identify the number and likely location of structural breaks. We find multiple breaks probably associated with the dra- matic falls of the stock market index. The results of the regression models over the different regimes, defined by the structural breaks, can vary markedly over time. This research is of value in macroeconomic forecasting and in the invest- ment strategy development. Keywords: Russian stock market, fundamental factors, structural instability, structural breaks, rolling regression, breakpoint tests. 1 Introduction Fundamental analysis is widely used to study the Russian stock market [1, 5, 12, 16, 17, 23, 27] and has great importance to study stock market deeply. Despite relative success of using fundamental analysis, there is now mounting evidence that the pa- rameters of regression models are unstable and subject to structural breaks. -

Company News SECURITIES MARKET NEWS LETTER Weekly

SSEECCUURRIIITTIIIEESS MMAARRKKEETT NNEEWWSSLLEETTTTEERR weekly Presented by: VTB Bank, Custody March 5, 2020 Issue No. 2020/08 Company News Polyus to become Moscow Exchange’s blue chip instead of Severstal On February 28, 2020 it was reported that the Moscow Exchange planned to include the ordinary shares of Russian gold producer Polyus in its Blue Chip index instead of the shares of steelmaker Severstal on March 20. The depository receipts of multi-industry holding En+ Group will be replaced with its shares, and the shares together with the depository receipts of payment system operator Qiwi will be considered to be added to the MOEX Russia Index and the RTS Index. Other changes to the indices include addition of depository receipts of real estate developer Etalon Group and exclusion of Seligdar from the Broad Market Index, inclusion of ordinary shares of fertilizer producer Acron and Pharmacy Chain 36.6 in the SMID Index, and exclusion of ordinary shares of oil company RussNeft and oil and gas pipe producer TMK from the Oil and Gas Index. The committee also recommended that the Moscow Exchange launch a new sectorial index for the Russian real estate industry. Mail.ru’s board of directors approves listing on Moscow Exchange On March 2, 2020 the board of directors of Russian Internet company Mail.ru Group approved a listing of global depositary receipts (GDRs) on the Moscow Exchange. The plan is for Mail.ru Group’s GDRs to begin trading in Moscow by July. There will not be any secondary issuance accompanying the listing. Russian antitrust clears Fortum to buy stake in Uniper On March 2, 2020 it was announced that Russia’s Federal Antimonopoly Service cleared Finland’s Fortum to acquire a 20.5% stake in Germany’s Uniper. -

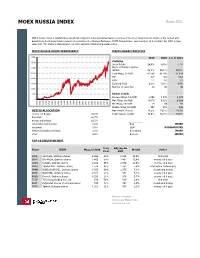

MOEX RUSSIA INDEX December 2019

MOEX RUSSIA INDEX December 2019 MOEX Russia Index is capitalization-weighted composite index calculated based on prices of the most liquid Russian stocks of the largest and dynamically developing Russian issuers presented on the Moscow Exchange. MOEX Russia Index was launched on September 22, 1997 at base value 100. The Index is calculated in real time and denominated in Russian rubles. MOEX RUSSIA INDEX PERFOMANCE MAIN CHARACTERISTICS 3,500 2017 2018 2019 Statistics 3,000 Index Return -5.5% 12.3% 28.6% Share of Russian equities 2,500 market 83.9% 84.1% 84.1% Total Mcap, bn RUB 30,644 34,432 42,580 2,000 P/E 7.8 8.5 6.7 1,500 P/BV 0.9 0.9 1.1 Dividend Yield 4.8% 5.9% 11.0% 1,000 Number of securities 45 42 39 500 Basket details Average MCap, bln RUB 681 820 1,092 0 Max MCap, bln RUB 4,861 4,584 6,070 2001 2006 2011 2015 2016 1998 1999 2000 2002 2003 2004 2005 2007 2008 2009 2010 2012 2013 2014 2017 2018 2019 1997 Min MCap, bln RUB 54 31 74 Median MCap, bln RUB 304 332 457 ASSETS ALLOCATION Max weight of issue 14.7% 15.5% 14.5% energy (oil & gas) 47.7% Top10 issues’ weight 71.8% 71.9% 72.6% financials 19.8% metals and mining 15.8% consumer 9.1% Код IMOEX telecommunication services 3.0% ISIN RU000A0JP7K5 electric utilities 2.5% Bloomberg IMOEX other 2.2% Reuters .IMOEX TOP 10 ISSUES WEIGHT Free- Adj cap, bn Ticker ISSUE Mcap, bn RUB Weight Sector Float RUB SBER Sberbank, Ordinary shares 5,499 48% 1,704 14.5% financials GAZP GAZPROM, Ordinary shares 6,070 46% 1,694 14.4% energy (oil & gas) LKOH LUKOIL, Ordinary shares 4,411 54% 1,608 13.6% -

Moscow Exchange Investor Presentation

April 2021 Investor presentation History of MOEX: the path of ongoing progress Foreign equities 174 commenced trading on MOEX New dividend policy Corporates granted with a minimum payout Inaugural direct access to ratio of 55% Sustainability MOEX completes its IPO; the FX Market Repo with CCP launched Report Launch of RUSFAR – Euroclear and Clearstream Money Market interest gain access to Trading in government rate benchmark corporate bonds in addition bonds moves to to government bonds T+1 settlement Equity trading moves to SPO of MOEX Shareholder electronic T+2 settlement Marketplace (Finuslugi.ru) voting becomes available MOEX share price, RUB price, share MOEX Launch of the launch Unified Collateral Pool New dividend policy: Launch of target payout = FCF, GCC repo Corporates admitted to min payout = 60% OTC bond platform of net profit 55 deposits with CCP launched Eurobonds start Grain trading trading on MOEX commences on MOEX Feb Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2012 2011 Launch of Central Merger of MICEX 2006 1995 1992 2013 Securities and RTS: National Clearing Russian Trading Moscow Interbank IPO of Moscow Depository Moscow Exchange (MOEX) Centre (NCC) System (RTS) Currency Exchange Exchange (MOEX) (CSD) established established established (MICEX) established 2001 1996 1993 1992 + Derivatives + Money Market + Bonds + FX Share price -

Monthly Economic Update

In this month’s recap: stocks descend as traders respond to the devaluation of the Chinese yuan as well as new developments in the ongoing U.S.-China trade talks; the price of gold rises, and bond yields fall. Monthly Economic Update Presented by Jason Palmer, September 2019 THE MONTH IN BRIEF The stock market had a tumultuous August, reacting to the sudden devaluation of the Chinese yuan and the escalation of the trade dispute between the U.S. and China. Ultimately, investors seemed more interested in risk aversion: the S&P 500 lost 1.81% for the month. Demand for bonds helped to send Treasury yields lower; prices of precious metals climbed. Away from the markets, monthly personal spending and retail sales gains were strong.1 DOMESTIC ECONOMIC HEALTH Tariffs and trade issues remained front and center in the Wall Street conversation. On August 1, the White House announced a 10% import tax on an additional $300 billion of Chinese goods coming to U.S. shores. (Most of these products are so-called “final” consumer goods, like clothing and shoes.) In a nod to importers and retailers, the White House stated on August 13 that this 10% tariff would be delayed until December 15 for certain products: toys, consumer electronics, and other items that are big sellers during the holiday shopping season. Effective December 15, tariffs will impact nearly all Chinese imports to the U.S.2 China soon retaliated, and the U.S. quickly responded. On August 25, China unveiled a plan to place tariffs on an additional $75 billion of U.S. -

ALROSA Investor Day 2020 10 March 2020 Disclaimer

ALROSA Investor Day 2020 10 March 2020 Disclaimer The below applies to the presentation (the “Presentation”) following this important notice, and you are therefore advised to read this For notes: important notice carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of this Presentation. This Presentation contains statements about future events and expectations that are forward-looking statements. Any statement herein (including, without limitation, a statement regarding our financial position, strategy, management plans and future objectives) that is not a statement of historical fact is a forward-looking statement that involves known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause ALROSA’s actual results, performance or achievements to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Past performance should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of future results, and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance. The information and opinions contained in this document are provided as at the date hereof (unless indicated otherwise) and are subject to change without notice. ALROSA assumes no obligation to update, supplement or revise the forward-looking statements contained herein to reflect actual results, changes in assumptions or changes in factors affecting these statements. This Presentation does not constitute or form part of and should not be construed as, an offer to sell -

Sustainability Equity Indices

February 2020 SUSTAINABILITY EQUITY INDICES RETURN OF EQUITY INDICES, 2012 – 2019* Moscow Exchange launched daily sustainability equity indices, the Responsibility and Transparency Index (MRRT) and Sustainability Vector Index (MRSV), on 1 April 2019, with data recalculated back to early 2012. The gauges were based on results of ESG analysis conducted annually by RSPP to construct sustainability indices of the same name. Current indices have been constructed by using data published by issuers in 2019. RSPP SUSTAINABILITY INDICES This analysis initiated by the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (the RSPP) explores how sustainability and corporate social responsibility management has progressed at the Russia’s largest companies. The input data are public corporate reporting of Russia’s top 100 companies in terms of sales volume (by RAEX Rating Agency and RBC). The SELECTION CRITERIA following indices will be calculated based on data analysis findings: Volume and quality of information Equity Index disclosure with regard to sustainable Responsibility and Transparency Index: the Responsibility and development and CSR in the public index intended to provide an overview of transparency corporate reporting. Identifying progress on information disclosure with regard to transparency leaders. sustainability and corporate social responsibility; Sustainable Development Vector Index: the Equity Index Positive dynamics in results. index reflects the progress in companies’ Sustainable Selection of the best performing performance in sustainability and corporate Development Vector companies. social responsibility areas. The indices are interrelated. The RSPP chooses out of the Responsibility and Transparency Index Return, % components, companies that are most effective in Index 2019 information disclosure and have a higher disclosure Annual 3Y 5Y frequency and quality. -

Presentation

ALROSA Capital Markets Day 2021 March 2, 2021 Disclaimer The below applies to the presentation (the “Presentation”) following this important notice, and you are therefore advised to read this important notice carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of this Presentation. This Presentation contains statements about future events and expectations that are forward-looking statements. Any statement herein (including, without limitation, a statement regarding our financial position, strategy, management plans and future objectives) that is not a statement of historical fact is a forward-looking statement that involves known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause ALROSA’s actual results, performance or achievements to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Past performance should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of future results, and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance. The information and opinions contained in this document are provided as at the date hereof (unless indicated otherwise) and are subject to change without notice. ALROSA assumes no obligation to update, supplement or revise the forward-looking statements contained herein to reflect actual results, changes in assumptions or changes in factors affecting these statements. This Presentation does not constitute or form part of and should not be construed as, an offer to sell or issue -

MOEX RUSSIA INDEX March 2021

MOEX RUSSIA INDEX March 2021 MOEX Russia Index is capitalization-weighted composite index calculated based on prices of the most liquid Russian stocks of the largest and dynamically developing Russian issuers presented on the Moscow Exchange. MOEX Russia Index was launched on September 22, 1997 at base value 100. The Index is calculated in real time and denominated in Russian rubles. MOEX RUSSIA INDEX PERFOMANCE MAIN CHARACTERISTICS 4 000 2019 2020 1 q. of 2021 Statistics 3 500 Index Return 28,6% 8,0% 7,7% 3 000 Share of Russian equities market 84,1% 89,1% 89,8% 2 500 Total Mcap, bn RUB 42 580 46 795 51 819 P/E 6,7 6,9 12,8 2 000 P/BV 1,1 1,0 1,1 1 500 Dividend Yield 6,4% 5,0% 4,4% Number of securities 39 45 44 1 000 500 Basket details Average MCap, bln RUB 1 092 1 040 1 178 0 Max MCap, bln RUB 6 070 5 852 6 266 1998 2003 2006 2008 2011 2013 2018 1999 2000 2001 2002 2004 2005 2007 2009 2010 2012 2014 2015 2016 2017 2019 2020 1997 Min MCap, bln RUB 74 39 41 Median MCap, bln RUB 457 415 548 ASSETS ALLOCATION Max weight of issue 14,5% 14,1% 14,0% energy (oil & gas) 40,2% Top10 issues’ weight 72,6% 70,9% 70,5% financials 20,7% metals and mining 18,5% information technologies 9,9% Код IMOEX consumer 4,0% ISIN RU000A0JP7K5 telecommunication services 2,2% Bloomberg IMOEX other 4,6% Reuters .IMOEX TOP 10 ISSUES WEIGHT Free- Adj cap, bn Ticker ISSUE Mcap, bn RUB Weight Sector Float RUB SBER Sberbank, Ordinary shares 6 266 48% 2 515 14,0% financials GAZP GAZPROM, Ordinary shares 5 403 50% 2 407 13,4% energy (oil & gas) LKOH LUKOIL, Ordinary shares -

Fundamental Factors Affecting the MOEX Russia Index: Retrospective Analysis1

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Fundamental Factors Affecting the MOEX Russia Index: Retrospective Analysis Lozinskaia, Agata and Saltykova, Anastasiia National Research University Higher School of Economics, Perm, Russia 23 September 2019 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/97308/ MPRA Paper No. 97308, posted 02 Dec 2019 10:01 UTC Fundamental Factors Affecting the MOEX Russia Index: Retrospective Analysis1 Agata Lozinskaia1[0000-0001-8723-275X] and Anastasiia Saltykova2[0000-0002-4147-6350] 1 National Research University Higher School of Economics, Perm, Russia 2 National Research University Higher School of Economics, Perm, Russia [email protected] Abstract. This paper is an empirical study of the changing nature of the de- pendence of fundamental factors on the stock market index, which is the trend identified earlier in the Russian stock market. We empirically test the impact of daily values of fundamental factors on the MOEX Russia Index from 2003 to 2018. The analysis of the ARIMA-GARCH (1,1) model with a rolling window reveals that the change in the power and direction of the influence of the fun- damental factors on the Russian stock market persists. The Quandt-Andrews breakpoint test and Bai-Perron test identify the number and likely location of structural breaks. We find multiple breaks probably associated with the dra- matic falls of the stock market index. The results of the regression models over the different regimes, defined by the structural breaks, can vary markedly over time. This research is of value in macroeconomic forecasting and in the invest- ment strategy development. Keywords: Russian stock market, fundamental factors, structural instability, structural breaks, rolling regression, breakpoint tests.