The Knot Group a Knot Is an Embedding of the Circle Into R3 (Or S3), K : S1 → R3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to Knot Theory and the Knot Group

AN INTRODUCTION TO KNOT THEORY AND THE KNOT GROUP LARSEN LINOV Abstract. This paper for the University of Chicago Math REU is an expos- itory introduction to knot theory. In the first section, definitions are given for knots and for fundamental concepts and examples in knot theory, and motivation is given for the second section. The second section applies the fun- damental group from algebraic topology to knots as a means to approach the basic problem of knot theory, and several important examples are given as well as a general method of computation for knot diagrams. This paper assumes knowledge in basic algebraic and general topology as well as group theory. Contents 1. Knots and Links 1 1.1. Examples of Knots 2 1.2. Links 3 1.3. Knot Invariants 4 2. Knot Groups and the Wirtinger Presentation 5 2.1. Preliminary Examples 5 2.2. The Wirtinger Presentation 6 2.3. Knot Groups for Torus Knots 9 Acknowledgements 10 References 10 1. Knots and Links We open with a definition: Definition 1.1. A knot is an embedding of the circle S1 in R3. The intuitive meaning behind a knot can be directly discerned from its name, as can the motivation for the concept. A mathematical knot is just like a knot of string in the real world, except that it has no thickness, is fixed in space, and most importantly forms a closed loop, without any loose ends. For mathematical con- venience, R3 in the definition is often replaced with its one-point compactification S3. Of course, knots in the real world are not fixed in space, and there is no interesting difference between, say, two knots that differ only by a translation. -

Knots and Links in Lens Spaces

Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna Dottorato di Ricerca in MATEMATICA Ciclo XXVI Settore Concorsuale di afferenza: 01/A2 Settore Scientifico disciplinare: MAT/03 Knots and links in lens spaces Tesi di Dottorato presentata da: Enrico Manfredi Coordinatore Dottorato: Relatore: Prof.ssa Prof. Giovanna Citti Michele Mulazzani Esame Finale anno 2014 Contents Introduction 1 1 Representation of lens spaces 9 1.1 Basic definitions . 10 1.2 A lens model for lens spaces . 11 1.3 Quotient of S3 model . 12 1.4 Genus one Heegaard splitting model . 14 1.5 Dehn surgery model . 15 1.6 Results about lens spaces . 17 2 Links in lens spaces 19 2.1 General definitions . 19 2.2 Mixed link diagrams . 22 2.3 Band diagrams . 23 2.4 Grid diagrams . 25 3 Disk diagram and Reidemeister-type moves 29 3.1 Disk diagram . 30 3.2 Generalized Reidemeister moves . 32 3.3 Standard form of the disk diagram . 36 3.4 Connection with band diagram . 38 3.5 Connection with grid diagram . 42 4 Group of links in lens spaces via Wirtinger presentation 47 4.1 Group of the link . 48 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 First homology group . 52 4.3 Relevant examples . 54 5 Twisted Alexander polynomials for links in lens spaces 57 5.1 The computation of the twisted Alexander polynomials . 57 5.2 Properties of the twisted Alexander polynomials . 59 5.3 Connection with Reidemeister torsion . 61 6 Lifting links from lens spaces to the 3-sphere 65 6.1 Diagram for the lift via disk diagrams . 66 6.2 Diagram for the lift via band and grid diagrams . -

Dynamics, and Invariants

k k On Groups Gn and Γn: A Study of Manifolds, Dynamics, and Invariants Vassily O. Manturov, Denis A. Fedoseev, Seongjeong Kim, Igor M. Nikonov A long time ago, when I first encountered knot tables and started un- knotting knots “by hand”, I was quite excited with the fact that some knots may have more than one minimal representative. In other words, in order to make an object simpler, one should first make it more complicated, for example, see Fig. 1 [72]: this diagram represents the trivial knot, but in order to simplify it, one needs to perform an increasing Reidemeister move first. Figure 1: Culprit knot Being a first year undergraduate student (in the Moscow State Univer- sity), I first met free groups and their presentation. The power and beauty, arXiv:1905.08049v4 [math.GT] 29 Mar 2021 and simplicity of these groups for me were their exponential growth and ex- tremely easy solution to the word problem and conjugacy problem by means of a gradient descent algorithm in a word (in a cyclic word, respectively). Also, I was excited with Diamond lemma (see Fig. 2): a simple condition which guarantees the uniqueness of the minimal objects, and hence, solution to many problems. Being a last year undergraduate and teaching a knot theory course for the first time, I thought: “Why do not we have it (at least partially) in knot theory?” 1 A A1 A2 A12 = A21 Figure 2: The Diamond lemma By that time I knew about the Diamond lemma and solvability of many problems like word problem in groups by gradient descent algorithm. -

Knot Theory and the Alexander Polynomial

Knot Theory and the Alexander Polynomial Reagin Taylor McNeill Submitted to the Department of Mathematics of Smith College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors Elizabeth Denne, Faculty Advisor April 15, 2008 i Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank Elizabeth Denne for her guidance through this project. Her endless help and high expectations brought this project to where it stands. I would Like to thank David Cohen for his support thoughout this project and through- out my mathematical career. His humor, skepticism and advice is surely worth the $.25 fee. I would also like to thank my professors, peers, housemates, and friends, particularly Kelsey Hattam and Katy Gerecht, for supporting me throughout the year, and especially for tolerating my temporary insanity during the final weeks of writing. Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Defining Knots and Links 3 2.1 KnotDiagramsandKnotEquivalence . ... 3 2.2 Links, Orientation, and Connected Sum . ..... 8 3 Seifert Surfaces and Knot Genus 12 3.1 SeifertSurfaces ................................. 12 3.2 Surgery ...................................... 14 3.3 Knot Genus and Factorization . 16 3.4 Linkingnumber.................................. 17 3.5 Homology ..................................... 19 3.6 TheSeifertMatrix ................................ 21 3.7 TheAlexanderPolynomial. 27 4 Resolving Trees 31 4.1 Resolving Trees and the Conway Polynomial . ..... 31 4.2 TheAlexanderPolynomial. 34 5 Algebraic and Topological Tools 36 5.1 FreeGroupsandQuotients . 36 5.2 TheFundamentalGroup. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 40 ii iii 6 Knot Groups 49 6.1 TwoPresentations ................................ 49 6.2 The Fundamental Group of the Knot Complement . 54 7 The Fox Calculus and Alexander Ideals 59 7.1 TheFreeCalculus ............................... -

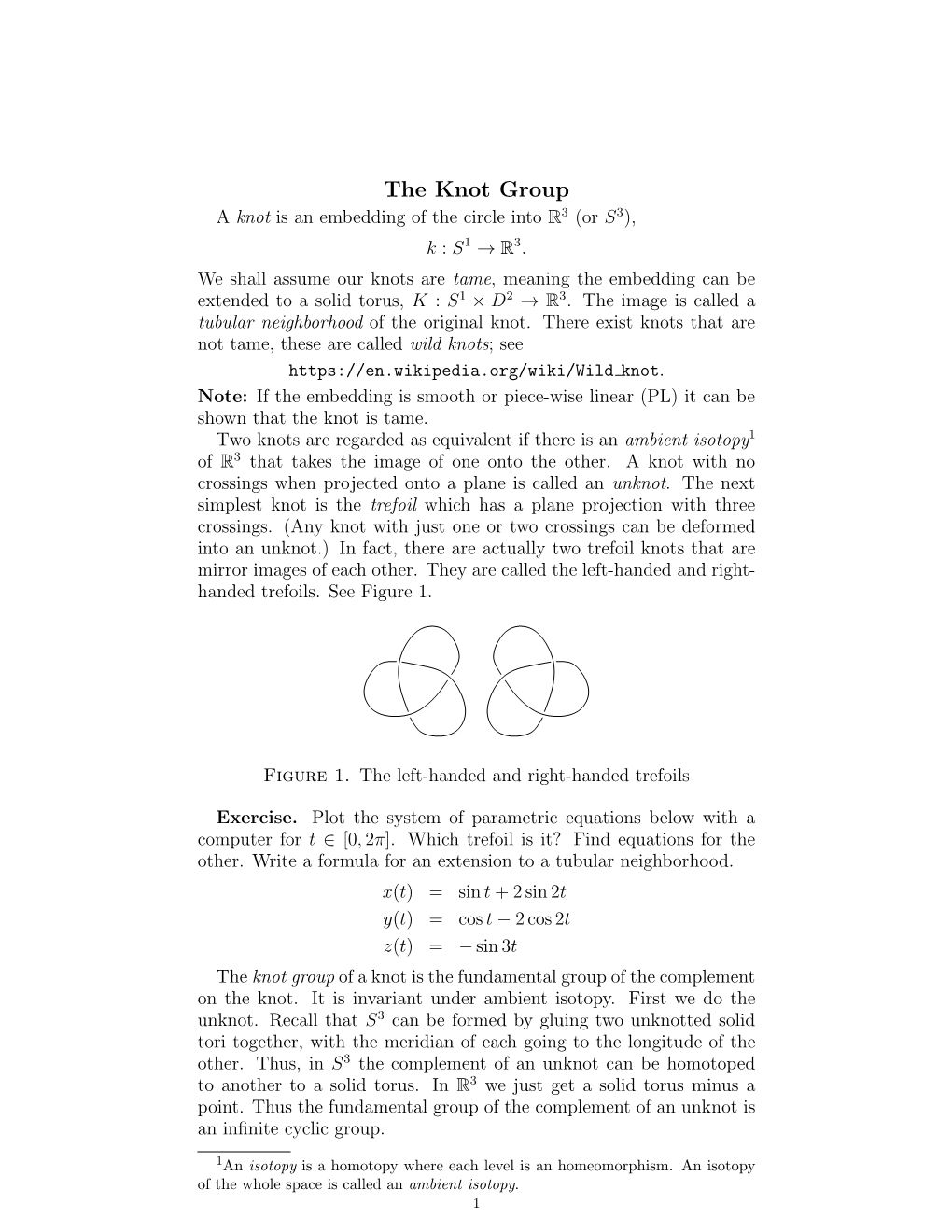

How Can We Say 2 Knots Are Not the Same?

How can we say 2 knots are not the same? SHRUTHI SRIDHAR What’s a knot? A knot is a smooth embedding of the circle S1 in IR3. A link is a smooth embedding of the disjoint union of more than one circle Intuitively, it’s a string knotted up with ends joined up. We represent it on a plane using curves and ‘crossings’. The unknot A ‘figure-8’ knot A ‘wild’ knot (not a knot for us) Hopf Link Two knots or links are the same if they have an ambient isotopy between them. Representing a knot Knots are represented on the plane with strands and crossings where 2 strands cross. We call this picture a knot diagram. Knots can have more than one representation. Reidemeister moves Operations on knot diagrams that don’t change the knot or link Reidemeister moves Theorem: (Reidemeister 1926) Two knot diagrams are of the same knot if and only if one can be obtained from the other through a series of Reidemeister moves. Crossing Number The minimum number of crossings required to represent a knot or link is called its crossing number. Knots arranged by crossing number: Knot Invariants A knot/link invariant is a property of a knot/link that is independent of representation. Trivial Examples: • Crossing number • Knot Representations / ~ where 2 representations are equivalent via Reidemester moves Tricolorability We say a knot is tricolorable if the strands in any projection can be colored with 3 colors such that every crossing has 1 or 3 colors and or the coloring uses more than one color. -

Knots and Seifert Surfaces

GRAU DE MATEMÀTIQUES Treball final de grau Knots and Seifert surfaces Autor: Eric Vallespí Rodríguez Director: Dr. Javier José Gutiérrez Marín Realitzat a: Departament de Matemàtiques i Informàtica Barcelona, 21 de juny de 2020 Agraïments Voldria agraïr primer de tot al Dr. Javier Gutiérrez Marín per la seva ajuda, dedicació i respostes immediates durant el transcurs de tot aquest treball. Al Dr. Ricardo García per tot i no haver pogut tutoritzar aquest treball, haver-me recomanat al Dr. Javier com a tutor d’aquest. A la meva família i als meus amics i amigues que m’han fet costat en tot moment (i sobretot en aquests últims mesos força complicats). I finalment a aquelles persones que "m’han descobert" aquest curs i que han fet d’aquest un de molt especial. 3 Abstract Since the beginning of the degree that I think that everyone should have the oportunity to know mathematics as they are and not as they are presented (or were presented) at a high school level. In my opinion, the answer to the question "why do we do this?" that a student asks, shouldn’t be "because is useful", it should be "because it’s interesting" or "because we are curious". To study mathematics (in every level) should be like solving an enormous puzzle. It should be a playful experience and satisfactory (which doesn’t mean effortless nor without dedication). It is this idea that brought me to choose knot theory as the main focus of my project. I wanted a theme that generated me curiosity and that it could be attrac- tive to other people with less mathematical background, in order to spread what mathematics are to me. -

Altering the Trefoil Knot

Altering the Trefoil Knot Spencer Shortt Georgia College December 19, 2018 Abstract A mathematical knot K is defined to be a topological imbedding of the circle into the 3-dimensional Euclidean space. Conceptually, a knot can be pictured as knotted shoe lace with both ends glued together. Two knots are said to be equivalent if they can be continuously deformed into each other. Different knots have been tabulated throughout history, and there are many techniques used to show if two knots are equivalent or not. The knot group is defined to be the fundamental group of the knot complement in the 3-dimensional Euclidean space. It is known that equivalent knots have isomorphic knot groups, although the converse is not necessarily true. This research investigates how piercing the space with a line changes the trefoil knot group based on different positions of the line with respect to the knot. This study draws comparisons between the fundamental groups of the altered knot complement space and the complement of the trefoil knot linked with the unknot. 1 Contents 1 Introduction to Concepts in Knot Theory 3 1.1 What is a Knot? . .3 1.2 Rolfsen Knot Tables . .4 1.3 Links . .5 1.4 Knot Composition . .6 1.5 Unknotting Number . .6 2 Relevant Mathematics 7 2.1 Continuity, Homeomorphisms, and Topological Imbeddings . .7 2.2 Paths and Path Homotopy . .7 2.3 Product Operation . .8 2.4 Fundamental Groups . .9 2.5 Induced Homomorphisms . .9 2.6 Deformation Retracts . 10 2.7 Generators . 10 2.8 The Seifert-van Kampen Theorem . -

On the Jones Polynomial and the Kauffman Bracket

On the Jones Polynomial constructing link invariants via braids & von Neumann algebras A Monica Queen Thesis Summer 2021 Abstract This expository essay is aimed at introducing the Jones polynomial. We will see the encapsu- lation of the Jones polynomial, which will involve topics in functional analysis and geometrical topology; making this essay an interdisciplinary area of mathematics. The presentation is based on a lot of different sources of material (check references), but we will mainly be giving an account on Jones’ papers ([25],[26],[27],[28],[29]) and Kauffman’s papers ([33],[34],[35]). A background in undergraduate Linear Algebra, Linear Analysis, Abstract Algebra, Commutative Algebra, & Topology is essential. It would also be useful if the reader has a background in Knot Theory & Operator Algebras. arXiv:2108.13835v2 [math.QA] 2 Sep 2021 Ars longa, vita brevis. This essay is dedicated to my grandmother Grace, who passed away during the start of writing this. CONTENTS 3 Contents A Introduction 6 B Knots & links 8 B.I Definingaknotandlink ................................ 8 B.II Linkequivalency.................................... 10 B.III Link diagrams and Reidemeister’s theorem . ...... 11 B.IV Orientation....................................... 14 B.V Invariants ........................................ 17 C The Kauffman bracket construction 19 C.I ‘states model’ and the Kauffman bracket polynomial . ...... 19 C.II Kauffman’s bracket polynomial definition of the Jones polynomial ......... 25 C.III The skein relation definition of the Jones polynomial . ....... 27 D The braid group Bn 31 D.I Braids .......................................... 32 D.II Representationsofgroups. ...... 33 D.III Thebraidgroup................................... .. 34 E The link between links & braids 41 E.I Motivation........................................ 46 F von Neumann algebras 47 F.I Background ...................................... -

Knot Group Epimorphisms DANIEL S

Knot Group Epimorphisms DANIEL S. SILVER and WILBUR WHITTEN Abstract: Let G be a finitely generated group, and let λ ∈ G. If there 3 exists a knot k such that πk = π1(S \k) can be mapped onto G sending the longitude to λ, then there exists infinitely many distinct prime knots with the property. Consequently, if πk is the group of any knot (possibly composite), then there exists an infinite number of prime knots k1, k2, ··· and epimorphisms · · · → πk2 → πk1 → πk each perserving peripheral structures. Properties of a related partial order on knots are discussed. 1. Introduction. Suppose that φ : G1 → G2 is an epimorphism of knot groups preserving peripheral structure (see §2). We are motivated by the following questions. Question 1.1. If G1 is the group of a prime knot, can G2 be other than G1 or Z? Question 1.2. If G2 can be something else, can it be the group of a composite knot? Since the group of a composite knot is an amalgamated product of the groups of the factor knots, one might expect the answer to Question 1.1 to be no. Surprisingly, the answer to both questions is yes, as we will see in §2. These considerations suggest a natural partial ordering on knots: k1 ≥ k2 if the group of k1 maps onto the group of k2 preserving peripheral structure. We study the relation in §3. 2. Main result. As usual a knot is the image of a smooth embedding of a circle in S3. Two knots are equivalent if they have the same knot type, that is, there exists an autohomeomorphism of S3 taking one knot to the other. -

Notation and Basic Facts in Knot Theory

Appendix A Notation and Basic Facts in Knot Theory In this appendix, our aim is to provide a quick review of basic terminology and some facts in knot theory, which we use or need in this book. This appendix lists them item by item (without proof); so we do no attempt to give a full rigorous treatments; Instead, we work somewhat intuitively. The reader with interest in the details could consult the textbooks [BZ, R, Lic, KawBook]. • First, we fix notation on the circle S1 := {(x, y) ∈ R2 | x2 + y2 = 1}, and consider a finite disjoint union S1. A link is a C∞-embedding of L :S1 → S3 in the 3-sphere. We denote often by #L the number of the disjoint union, and denote the image Im(L) by only L for short. If #L is 1, L is usually called a knot, and is written K instead. This book discusses embeddings together with orientation. For an oriented link L, we denote by −L the link with its orientation reversed, and by L∗ the mirror image of L. • (Notations of link components). Given a link L :S1 → S3, let us fix an open tubular neighborhood νL ⊂ S3. Throughout this book, we denote the complement S3 \ νL by S3 \ L for short. Since we mainly discuss isotopy classes of S3 \ L,we may ignore the choice of νL. 2 • For example, for integers s, t ∈ Z , the torus link Ts,t (of type (s, t)) is defined by 3 2 s t 2 2 S Ts,t := (z,w)∈ C z + w = 0, |z| +|w| = 1 . -

On the Study of Chirality of Knots Through Polynomial Invariants

Treball final de grau GRAU DE MATEMÀTIQUES Facultat de Matemàtiques i Informàtica Universitat de Barcelona KNOT THEORY: On the study of chirality of knots through polynomial invariants Autor: Sergi Justiniano Claramunt Director: Dr. Javier José Gutiérrez Marín Realitzat a: Departament de Matemàtiques i Informàtica Barcelona, January 18, 2019 Contents Abstract ii Introduction iii 1 Mathematical bases 1 1.1 Definition of a knot . .1 1.2 Equivalence of knots . .4 1.3 Knot projections and diagrams . .6 1.4 Reidemeister moves . .8 1.5 Invariants . .9 1.6 Symmetries, properties and generation of knots . 11 1.7 Tangles and Conway notation . 12 2 Jones Polynomial 15 2.1 Introduction . 15 2.2 Rules of bracket polynomial . 16 2.3 Writhe and invariance of Jones polynomial . 18 2.4 Main theorems and applications . 22 3 HOMFLY and Kauffman polynomials on chirality detection 25 3.1 HOMFLY polynomial . 25 3.2 Kauffman polynomial . 28 3.3 Testing chirality . 31 4 Conclusions 33 Bibliography 35 i Abstract In this project we introduce the theory of knots and specialize in the compu- tation of the knot polynomials. After presenting the Jones polynomial, its two two-variable generalizations are also introduced: the Kauffman and HOMFLY polynomial. Then we study the ability of these polynomials on detecting chirality, obtaining a knot not detected chiral by the HOMFLY polynomial, but detected chiral by the Kauffman polynomial. Introduction The main idea of this project is to give a clear and short introduction to the theory of knots and in particular the utility of knot polynomials on detecting chirality of knots. -

The Ways I Know How to Define the Alexander Polynomial

ALL THE WAYS I KNOW HOW TO DEFINE THE ALEXANDER POLYNOMIAL KYLE A. MILLER Abstract. These began as notes for a talk given at the Student 3-manifold seminar, Spring 2019. There seems to be many ways to define the Alexander polynomial, all of which are somehow interrelated, but sometimes there is not an obvious path between any two given definitions. As the title suggests, this is an exploration of all the ways I know how to define this knot invariant. While we will touch on a number of facts and properties, these notes are not meant to be a complete survey of the Alexander polynomial. Contents 1. Introduction2 2. Alexander’s definition2 2.1. The Dehn presentation2 2.2. Abelianization4 2.3. The associated matrix4 3. The Alexander modules6 3.1. Orders7 3.2. Elementary ideals8 3.3. The Fox calculus 10 3.4. Torus knots 13 3.5. The Wirtinger presentation 13 3.6. Generalization to links 15 3.7. Fibered knots 15 3.8. Seifert presentation 16 3.9. Duality 18 4. The Conway potential 18 4.1. Alexander’s three-term relation 20 5. The HOMFLY-PT polynomial 24 6. Kauffman state sum 26 6.1. Another state sum 29 7. The Burau representation 29 8. Vassiliev invariants 29 9. The Alexander quandle 29 9.1. Projective Alexander quandles 33 10. Reidemeister torsion 33 11. Knot Floer homology 33 References 33 Date: May 3, 2019. 1 DRAFT 2020/11/14 18:57:28 2 KYLE A. MILLER 1. Introduction Recall that a link is an embedded closed 1-manifold in S3, and a knot is a 1-component link.