The Sadness of Great Fame: the Conflict Between Individuality and Expectation in the Works of Don Delillo and Jim Morrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology Fa Ct Or

Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price Origin Label Genre Release A40355 A & P Live In Munchen + Cd 2 Dvd € 24 Nld Plabo Pun 2/03/2006 A26833 A Cor Do Som Mudanca De Estacao 1 Dvd € 34 Imp Sony Mpb 13/12/2005 172081 A Perfect Circle Lost In the Bermuda Trian 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Virgi Roc 29/04/2004 204861 Aaliyah So Much More Than a Woman 1 Dvd € 19 Eu Ch.Dr Doc 17/05/2004 A81434 Aaron, Lee Live -13tr- 1 Dvd € 24 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81435 Aaron, Lee Video Collection -10tr- 1 Dvd € 22 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81128 Abba Abba 16 Hits 1 Dvd € 20 Nld Univ Pop 22/06/2006 566802 Abba Abba the Movie 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 29/09/2005 895213 Abba Definitive Collection 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 22/08/2002 824108 Abba Gold 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 21/08/2003 368245 Abba In Concert 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 25/03/2004 086478 Abba Last Video 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Univ Pop 15/07/2004 046821 Abba Movie -Ltd/2dvd- 2 Dvd € 29 Nld Polar Pop 22/09/2005 A64623 Abba Music Box Biographical Co 1 Dvd € 18 Nld Phd Doc 10/07/2006 A67742 Abba Music In Review + Book 2 Dvd € 39 Imp Crl Doc 9/12/2005 617740 Abba Super Troupers 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 14/10/2004 995307 Abbado, Claudio Claudio Abbado, Hearing T 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Tdk Cls 29/03/2005 818024 Abbado, Claudio Dances & Gypsy Tunes 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 12/12/2001 876583 Abbado, Claudio In Rehearsal 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 23/06/2002 903184 Abbado, Claudio Silence That Follows the 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 5/09/2002 A92385 Abbott & Costello Collection 28 Dvd € 163 Eu Univ Com 28/08/2006 470708 Abc 20th Century Masters -

List of Available Videos

Artist Concert 3 Doors Down Live at the Download Festival 3 Doors Down Live At The Tabernacle 2014 30 Odd Foot Of Grunts Live at Soundstage 30 Seconds To Mars Live At Download Festival 2013 5 Seconds of Summer How Did We End Up Here? 6ft Hick Notes from the Underground A House Live on Stage A Thousand Horses Real Live Performances ABBA Arrival: The Ultimate Critical Review ABBA The Gold Singles Above And Beyond Acoustic AC/DC AC/DC - No Bull AC/DC In Performance AC/DC Live At River Plate\t AC/DC Live at the Circus Krone Acid Angels 101 A Concert - Band in Seattle Acid Angels And Big Sur 101 Episode - Band in Seattle Adam Jensen Live at Kiss FM Boston Adam Lambert Glam Nation Live Aerosmith Rock for the Rising Sun Aerosmith Videobiography After The Fire Live at the Greenbelt Against Me! Live at the Key Club: West Hollywood Aiden From Hell with Love Air Eating Sleeping Waiting and Playing Air Supply Air Supply Live in Toronto Air Supply Live in Hong Kong Akhenaton Live Aux Docks Des Sud Al Green Everything's Going To Be Alright Alabama and Friends Live at the Ryman Alain Souchon J'veux Du Live Part 2 Alanis Morissette Guitar Center Sessions Alanis Morissette Live at Montreux 2012 Alanis Morissette Live at Soundstage Albert Collins Live at Montreux Alberta Cross Live At The ATO Cabin Alejandro Fernández Confidencias Reales Alejandro Sanz El Alma al Aire en Concierto Ali Campbell Live at the Shepherds Bush Empire Alice Cooper AVO Session Alice Cooper Brutally Live Alice Cooper Good To See You Again Alice Cooper Live at Montreux Alice Cooper -

Manchester United Training Session Key Information Sheet

Manchester United Training Session Key Information Sheet Date/Time - July 30th at 10:30AM Location - East River 6th Street Park in lower Manhattan located at 6th and the FDR. - There is no parking at the event. - The Soccer Field is located at 6th Street and the FDR, between a baseball field (north) and field under renovation (south). Event Schedule - The gate opens at 10:00AM. - The event starts promptly at 10:30AM with a Manchester United 1 hour training session followed by a: 45 clinic. - The event ends at 12:30PM. Event Passes - There is a limited supply of passes and they are first come, first served so place your order early - This is an invite only event and you will be required to show your pass at the South Gate of the park for entrance into the event. - After we receive your Pass Request Form, you will receive an email or call from MKTG.partners to confirm pass availability and let you know when you will receive your passes. - Your passes will be mailed to you. - Passes cannot be picked up at the park. Rules - No food/drink/coolers allowed. - There will be food concessions at the event. JULY 30TH MANCHESTER UNITED TRAINING SESSION PASS FORM To order your passes, please fill out this form completely and neatly and fax to 212.253.1625, Attn: Manchester United Training Session. Passes are free and first come, first served. You need the pass for entry into the event. Don t delay because there s only a limited supply. Organization Name: Contact Name: Street Address: City: State: Zip Code: Phone Number: Email Address: Number of Passes Requested: Tickets will be mailed via overnight courier. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. November 23, 2020 to Sun

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. November 23, 2020 to Sun. November 29, 2020 Monday November 23, 2020 2:30 PM ET / 11:30 AM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar Tom Green Live Rock & Roll Beach Party - It’s a music festival Sammy-style. Join the Red Rocker for the first an- Marlon Wayans - Comrades in comedy convene Tom trades laughs with Marlon Wayans and nual High Tide Beach Party & Car Show. Vince Neil, Kevin Cronin, Eddie Trunk, Tre Cool, and Eddie Harland Williams. An American comedy dynasty is represented when actor/comedian/writer Money meet up with Sammy at the beach along with 14,000 of their closest friends. Marlon Wayans grabs a seat across from Tom. And he always brings it, whether plying his trade in sit-coms, feature films, or a sketch and variety series like In Living Color. The sardonic Williams, 3:00 PM ET / 12:00 PM PT an accomplished stand-up with a string of appearances on late-night TV, is currently starring in Live From Daryl’s House the sit-com Package Deal. Rob Thomas - Multi Grammy winner Rob Thomas teams up with Daryl Hall on hit songs like “3 AM” and “She’s Gone” on this episode of Live From Daryl’s House. 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT The Very VERY Best of the 70s 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT Amazing Toys - From silly to groundbreaking, these play things filled everyone with hours of fun. -

Watertight Doors Awareness

Watertight doors Awareness 1 Content Watertight sliding doors 1. Introduction and lessons learned 2. Technical, operational and maintenance issues 3. Summary and recommendations 2 Safety onboard In the 21st century • Safety onboard is better than ever. • The future of seafaring continues to evolve in response to economic, political, demographic, and technological trends. • The maritime industry work actively to improve safety records. • Marine transportation can be considered one of the safest means of passenger transport overall. Safety onboard has been improved through a combination of technology, cultural & training improvements 3 and regulations Safety onboard Modern vessels are equipped with an array of safety innovations 4 Source: www.cruisemapper.com Safety onboard Decline in total losses worldwide – 2006 to 2015 Large shipping losses have declined by 45% Foundered (sunk or submerged) is the main cause of loss over the past decade, driven by an accounting for half (50%) of all losses over the past decade. increasingly robust safety environment and Grounding is the second major cause (20%) self regulation. Fire is the third major cause (10%) Collision is the fourth major cause (7.3%) Source: Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty, Safety and Shipping Review 2015 Watertight doors are important in case of foundering, 5 grounding, collision and contact damages. Awareness topic Power operated watertight sliding doors Safety of the ship Safety of the people - Increase the integrity of the watertight doors as a barrier in case of internal flooding or water ingress after damage. - Create a better understanding of how the watertight doors are designed, and should be operated and maintained during normal and emergency conditions. -

Great Jones Street, 1958 Enamel on Canvas Collection of Irma and Norman Braman

Great Jones Street, 1958 Enamel on canvas Collection of Irma and Norman Braman Yugatan, 1958 Oil and enamel on canvas Private collection Delta, 1958 Enamel on canvas Private collection Jill, 1959 Enamel on canvas Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1962 Die Fahne hoch!, 1959 Enamel on canvas Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene M. Schwartz and purchase with funds from the John I. H. Baur Purchase Fund, the Charles and Anita Blatt Fund, Peter M. Brant, B. H. Friedman, the Gilman Foundation, Inc., Susan Morse Hilles, The Lauder Foundation, Frances and Sydney Lewis, the Albert A. List Fund, Philip Morris Incorporated, Sandra Payson, Mr. and Mrs. Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Percy Uris, Warner Communications Inc., and the National Endowment for the Arts 75.22 Avicenna, 1960 Aluminum oil paint on canvas The Menil Collection, Houston Marquis de Portago (first version), 1960 Aluminum oil paint on canvas Collection of Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Creede I, 1961 Copper oil paint on canvas Collection of Martin Z. Margulies Creede II, 1961 Copper oil paint on canvas Private collection Plant City, 1963 Zinc chromate on canvas Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Agnes Gund in memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, 2008 1 Gran Cairo, 1962 Alkyd on canvas Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art 63.34 Miniature Benjamin Moore series (New Madrid, Sabine Pass, Delaware Crossing, Palmito Ranch, Island No. 10, Hampton Roads), 1962 Alkyd on canvas (Benjamin Moore flat wall paint); six paintings Brooklyn Museum; gift of Andy Warhol 72.167.1–6 Marrakech, 1964 Fluorescent alkyd on canvas The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; gift of Mr. -

Am. Singer/Songwriter,Flott.Covret Av Bl.A Spooky.Tooth,J.Driscoll. Utgitt I 1993

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP A ATCO REC7567- AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 1995 EUR CD 92418-2 ACKLES, DAVID FIVE & DIME 2004 RAVENREC. AUST. CD Am. singer/songwriter,flott.Covret av bl.a Spooky.Tooth,J.Driscoll. Utgitt i 1993. Cd utg. fra 2004 XL RECORDINGS ADELE 21 2011 EUR CD XLLP 520 ADELE 25 2015 XLCD 740 EUR CD ADIEMUS SONGS OF SANCTUARY 1995 CDVE 925 HOL CD Prosjektet til ex Soft Machine medlem Karl Jenkins. Middelalderstemnig og mye flott koring. AEROSMITH PUMP 1989 GEFFEN RECORDS USA CD Med Linda Hoyle på flott vocal, Mo Foster, Mike Jupp.Cover av Keef. Høy verdi på original vinyl AFFINITY AFFINITY 1970 VERTIGO UK CD Vertigo swirl. AFTER CRYING OVERGROUND MUSIC 1990 ROCK SYMPHONY EUR CD Bulgarsk progband, veldig bra. Tysk eksperimentell /elektronisk /prog musikk. Østen insirert album etter Egyptbesøk. Lp utgitt AGITATION FREE MALESCH 2008 SPV 42782 GER CD 1972. AIR MOON SAFARI 1998 CDV 2848 EUR CD Frank duo, mye keyboard og synthes. VIRGIN 72435 966002 AIR TALKIE WALKIE 2004 EUR CD 8 ALBION BAND ALBION SUNRISE 1994-1999 2004 CASTLE MUSIC UK CDX2 Britisk folkrock med bl.a A.Hutchings,S.Nicol ex.Fairport Convention ALBION BAND M/ S.COLLINS NO ROSES 2004 CASTLE MUSIC UK CD Britisk folk rock. Opprinnelig på Pegasus Rec. I 1971. CD utg fra 2004. Shirley Collins på vocal. ALICE IN CHAINS DIRT 1992 COLOMBIA USA CD Godt album, flere gode låter, bl.a Down in a hole. ALICE IN CHAINS SAP 1992 COLOMBIA USA CD Ep utgivelse med 4 sterke låter, Brother, Got me wrong, Right turn og I am inside ALICE IN CHAINS ALICE IN CHAINS 1995 COLOMBIA USA CD Tungt, smådystert og bra. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00 -

41 Great Jones Street by 41 Great Jones Holdings, LLC

April 30, 2015 Recommendation on ULURP Application No. C 150146 ZSM – 41 Great Jones Street By 41 Great Jones Holdings, LLC PROPOSED ACTION 41 Great Jones Holdings, LLC1 (“the applicant”) seeks a special permit pursuant to Section 74- 711 of the Zoning Resolution (“ZR”) to modify use regulations of § 42-10 to allow Use Group 2 (residential use) on the cellar, ground floor, second through fifth floors, and proposed sixth floor of an existing five story building at 41 Great Jones Street (Block 530, Lot 27) in an M1-5B zoning district within the NoHo Historic District Extension of Manhattan Community District 2. Pursuant to ZR § 74-711, applicants may request a special permit to modify the use regulations of zoning lots that contain landmarks or are within historic districts as designated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission (“LPC”). In order for the City Planning Commission (“CPC”) to grant use modifications, the applicant must first meet the following conditions: 1. the LPC has issued a report stating that the applicant will establish a continuing maintenance program for the preservation of the subject building or buildings and that such use or bulk modifications, or restorative work required under this continuing maintenance program will contribute to a preservation purpose;2 2. the application shall include a Certificate of Appropriateness, other permit, or report from LPC stating that such bulk modifications relate harmoniously to the subject landmark building in the Historic District3; and 3. the maximum number of permitted dwelling units is as set forth in ZR § 15-111.4 Further, in order to grant a special permit, the CPC must find that: 1. -

14 East 4Th Street

GREENWICH VILLAGE OFFICE/MEDICAL SPACE FOR LEASE 14 EAST 4TH STREET THE SILK BUILDING Between Broadway and Lafayette Street, New York, NY GREENWICH VILLAGE OFFICE/MEDICAL SPACE FOR LEASE 14 EAST 4TH STREET THE SILK BUILDING Between Broadway and Lafayette Street, New York, NY For Lease: Building Features Partial 4th Floor: 1,863 RSF • Located in the legendary Silk Building, a first-class building that Asking Rent: $11,500 per month features modernized building systems and a gorgeous marble Term: Up to 10 years lobby which is attended 24/7. Possession: Immediate • Ideally located in the heart of Greenwich Village and Noho on Space Features: the tree-lined East 4th Street and Lafayette. • Four oversized, operable windows that floods the space • SoulCycle and Blink Gym are located in the building. with air and natural light. • Steps from Lafayette Restaurant, La Colombe, the new Lavain • Wet columns on both sides of the space make it an ideal Bakery, Kith, Washington Square Park and the Bowery and for medical practitioners and dentists. There is a private Standard Hotels. bathroom within the space. • Close proximity to the 6, N, R, B, D, F & M trains. • Can accommodate up to four windowed offices, a conference room, a reception area, kitchenette and an open area for desks. • Original hardwood flooring with high ceilings creates a WWW.RUDDERPG.COM/14E4 loft-like and spacious feeling. • Excellent presence off the elevators. Rudder Property Group Michael Rudder Justin Harris 36 West 44th Street Office: (212) 966-3611 Office: (212) 966-5638 Suite -

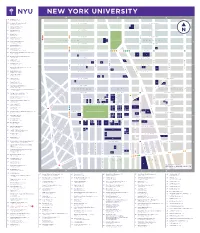

Nyu-Downloadable-Campus-Map.Pdf

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY 64 404 Fitness (B-2) 404 Lafayette Street 55 Academic Resource Center (B-2) W. 18TH STREET E. 18TH STREET 18 Washington Place 83 Admissions Office (C-3) 1 383 Lafayette Street 27 Africa House (B-2) W. 17TH STREET E. 17TH STREET 44 Washington Mews 18 Alumni Hall (C-2) 33 3rd Avenue PLACE IRVING W. 16TH STREET E. 16TH STREET 62 Alumni Relations (B-2) 2 M 25 West 4th Street 3 CHELSEA 2 UNION SQUARE GRAMERCY 59 Arthur L Carter Hall (B-2) 10 Washington Place W. 15TH STREET E. 15TH STREET 19 Barney Building (C-2) 34 Stuyvesant Street 3 75 Bobst Library (B-3) M 70 Washington Square South W. 14TH STREET E. 14TH STREET 62 Bonomi Family NYU Admissions Center (B-2) PATH 27 West 4th Street 5 6 4 50 Bookstore and Computer Store (B-2) 726 Broadway W. 13TH STREET E. 13TH STREET THIRD AVENUE FIRST AVENUE FIRST 16 Brittany Hall (B-2) SIXTH AVENUE FIFTH AVENUE UNIVERSITY PLACE AVENUE SECOND 55 East 10th Street 9 7 8 15 Bronfman Center (B-2) 7 East 10th Street W. 12TH STREET E. 12TH STREET BROADWAY Broome Street Residence (not on map) 10 FOURTH AVE 12 400 Broome Street 13 11 40 Brown Building (B-2) W. 11TH STREET E. 11TH STREET 29 Washington Place 32 Cantor Film Center (B-2) 36 East 8th Street 14 15 16 46 Card Center (B-2) W. 10TH STREET E. 10TH STREET 7 Washington Place 17 2 Carlyle Court (B-1) 18 25 Union Square West 19 10 Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò (A-1) W. -

Act 1 Scene 7

Act 1 Scene 7 (Enter Macbeth) MACBETH If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well It were done quickly: if th’assassination Could trammel up the consequence and catch With his surcease success: that but this blow Might be the be-all and the end-all — here, 5 But here, upon this bank and shoal of time, We’d jump the life to come. But in these cases We still have judgement here, that we but teach Bloody instructions, which, being taught, return To plague th’inventor: this even-handed justice 10 Commends th’ingredients of our poisoned chalice To our own lips. He’s here in double trust: First, as I am his kinsman and his subject, Strong both against the deed: then, as his host, Who should against his murderer shut the door, 15 Not bear the knife myself. Besides, this Duncan Hath borne his faculties so meek, hath been So clear in his great office, that his virtues Will plead like angels, trumpet-tongued, against The deep damnation of his taking-off: 20 And pity, like a naked new-born babe, Striding the blast, or heaven’s cherubin, horsed Upon the sightless couriers of the air, Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye, That tears shall drown the wind. I have no spur 25 To prick the sides of my intent, but only Vaulting ambition, which o’erleaps itself And falls on th’other.— (Enter Lady Macbeth) How now? What news? LADY MACBETH He has almost supped. Why have you left the chamber? MACBETH Hath he asked for me? 30 LADY MACBETH Know you not he has? MACBETH We will proceed no further in this business: He hath honoured me of late, and I have bought Golden opinions from all sorts of people, Which would be worn now in their newest gloss, 35 Not cast aside so soon.