128 West 18Th Street Stable and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

NYC ADZONE™ Detailsve MIDTOWN EAST AREA Metropolitan Mt Sinai E 117Th St E 94Th St

ve y Hudson Pkwy Pinehurst A Henr W 183rd St W 184th St George W CabriniW Blvd 181st St ve ashington Brdg Lafayette Plz ve Colonel Robert Magaw Pl W 183rd St W 180th St Saint Nicholas A er Haven A Trans Mahattan Exwy W 182nd St 15 / 1A W 178th St W 179th St ve Laurel Hill T W 177th St Washington Brdg W 178th St Audubon A Cabrini Blvd ve W 176th St ve W 177th St Riverside Dr Haven A S Pinehurst A W 175th St Alexander Hamiliton W 172nd St W 174th St Brdg ve W 171st St W 173rd St W 170th St y Hudson Pkwy Pinehurst A Henr ve W 184th St W 169th St W 183rd St 14 y Hudson Pkwy George W Lafayette Plz CabriniW Blvd 181st St ve Pinehurst A ashington Brdg ve High Brdg W 168th St Henr W 183rd St W 184th St ve Colonel High Bridge Robert Magaw Pl W 183rd St y Hudson Pkwy Cabrini Blvd W 180th St George W W 165th St Lafayette Plz W 181st St ve Pinehurst A Park ashington Brdg Henr Saint Nicholas A er Haven A TransW Mahattan 184th St Exwy W 182nd St Presbyterian 15 / 1A W 183rd St ve Colonel W 167th St Robert Magaw Pl W 183rd St Hospital ve Cabrini Blvd W 179th St W 180th WSt 178th St ve George W Lafayette Plz W 181st St Jumel Pl ashington B W 166th St ve Laurel Hill T W 163rd St Saint Nicholas A er rdg Haven A Trans Mahattan Exwy W 182nd St W Riverside Dr W 177th St ashington Brdg ve 15W 164th / 1A St Colonel Robert Magaw Pl W 183rd StW 178th St Audubon A W 162nd St ve e W 166th St Cabrini Blvd v W 180th St ve W 179th St ve A W 178th St W 176th St W 161st St s Edgecombe A W 165th veSt Saint Nicholas A W 177th St er Laurel Hill T Haven A a W 182nd St Transl -

Manchester United Training Session Key Information Sheet

Manchester United Training Session Key Information Sheet Date/Time - July 30th at 10:30AM Location - East River 6th Street Park in lower Manhattan located at 6th and the FDR. - There is no parking at the event. - The Soccer Field is located at 6th Street and the FDR, between a baseball field (north) and field under renovation (south). Event Schedule - The gate opens at 10:00AM. - The event starts promptly at 10:30AM with a Manchester United 1 hour training session followed by a: 45 clinic. - The event ends at 12:30PM. Event Passes - There is a limited supply of passes and they are first come, first served so place your order early - This is an invite only event and you will be required to show your pass at the South Gate of the park for entrance into the event. - After we receive your Pass Request Form, you will receive an email or call from MKTG.partners to confirm pass availability and let you know when you will receive your passes. - Your passes will be mailed to you. - Passes cannot be picked up at the park. Rules - No food/drink/coolers allowed. - There will be food concessions at the event. JULY 30TH MANCHESTER UNITED TRAINING SESSION PASS FORM To order your passes, please fill out this form completely and neatly and fax to 212.253.1625, Attn: Manchester United Training Session. Passes are free and first come, first served. You need the pass for entry into the event. Don t delay because there s only a limited supply. Organization Name: Contact Name: Street Address: City: State: Zip Code: Phone Number: Email Address: Number of Passes Requested: Tickets will be mailed via overnight courier. -

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

25Th Street Showrooms Showrooms Throughout

40°49'0"N 73°58'0"W 73°57'0"W 40°48'0"N 73°56'0"W 73°55'0"W E 119th St E 119th St e W 119th St e W 119th St W 119th St v v A A Central Harlem e e v v e St Nicholas Ave m A e d a A E 118th St i E 118th St v W 118th St d s W 118th St h t r Columbia n A g e e a 5 t t v t n t s i n Barnard r A n a m o 40°49'0"N University r e D h x E 117th St E 117th St A o m v W 117th St College n o e e A a n r M d i 3rd Ave 3rd e a h M s l L t g C 8 n E 116th St W 116th St i W 116th St W 116th St E 116th St n r o M W 115th St W 115th St W 115th St E 115th St E 115th St d v l e e Riverside Dr v e B v East Harlem v A r A E 114th St J W 114th St A W 114th St n Pleasant Ave l n o l t k o e r s North g i n Morningside a w i d P E 113th St x a W 113th St W 113th St o e e Park e P v L M Jefferson v 5th Ave e A n v A e iver x o e A v t t E 112th St E 112th St o W 112th St W 112th St s A W 112th St y g n Park n R 1 a a e d t l St Nicholas Ave m L i t r a a C d B h Manhattan r Frawley Cir E 111th St W 111th St W 111th St E 111th St W 111th St n m e Fred Douglass Cir t a s a Psychiatric h M d m g Riverside Dr u A A Central Park N E 110th St ral Pky W 110th St E 110th St m Cathed Center o r o e Wards Is Rd o le b v b E 109th St A E 109th St 21 C W 109th St W 109th St i st Dr r o n 40°47'0"N 73°59'0"W T o ar k Harlem Meer s i r d E 108th St E 108th St Ditmars Blvd West 108th St W 108th St W 108th St a H o n C M W End Ave Y e West Dr Co 107th St Dr R D F g E nrail Railroad Riverside Park W 107th St W 107th St E 107th St r w Broadway e East Dr v e Randalls-Wards W A Be -

151 Canal Street, New York, NY

CHINATOWN NEW YORK NY 151 CANAL STREET AKA 75 BOWERY CONCEPTUAL RENDERING SPACE DETAILS LOCATION GROUND FLOOR Northeast corner of Bowery CANAL STREET SPACE 30 FT Ground Floor 2,600 SF Basement 2,600 SF 2,600 SF Sub-Basement 2,600 SF Total 7,800 SF Billboard Sign 400 SF FRONTAGE 30 FT on Canal Street POSSESSION BASEMENT Immediate SITE STATUS Formerly New York Music and Gifts NEIGHBORS 2,600 SF HSBC, First Republic Bank, TD Bank, Chase, AT&T, Citibank, East West Bank, Bank of America, Industrial and Commerce Bank of China, Chinatown Federal Bank, Abacus Federal Savings Bank, Dunkin’ Donuts, Subway and Capital One Bank COMMENTS Best available corner on Bowery in Chinatown Highest concentration of banks within 1/2 mile in North America, SUB-BASEMENT with billions of dollars in bank deposits New long-term stable ownership Space is in vanilla-box condition with an all-glass storefront 2,600 SF Highly visible billboard available above the building offered to the retail tenant at no additional charge Tremendous branding opportunity at the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge with over 75,000 vehicles per day All uses accepted Potential to combine Ground Floor with the Second Floor Ability to make the Basement a legal selling Lower Level 151151 C anCANALal Street STREET151 Canal Street NEW YORKNew Y |o rNYk, NY New York, NY August 2017 August 2017 AREA FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS/BRANCH DEPOSITS SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LUDLOW STREET ESSEX STREET SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LEGEND LUDLOW -

Manhattan N.V. Map Guide 18

18 38 Park Row. 113 37 101 Spring St. 56 Washington Square Memorial Arch. 1889·92 MANHATTAN N.V. MAP GUIDE Park Row and B kman St. N. E. corner of Spring and Mercer Sts. Washington Sq. at Fifth A ve. N. Y. Starkweather Stanford White The buildings listed represent ali periods of Nim 38 Little Singer Building. 1907 19 City Hall. 1811 561 Broadway. W side of Broadway at Prince St. First erected in wood, 1876. York architecture. In many casesthe notion of Broadway and Park Row (in City Hall Perk} 57 Washington Mews significant building or "monument" is an Ernest Flagg Mangin and McComb From Fifth Ave. to University PIobetween unfortunate format to adhere to, and a portion of Not a cast iron front. Cur.tain wall is of steel, 20 Criminal Court of the City of New York. Washington Sq. North and E. 8th St. a street or an area of severatblocks is listed. Many glass,and terra cotta. 1872 39 Cable Building. 1894 58 Housesalong Washington Sq. North, Nos. 'buildings which are of historic interest on/y have '52 Chambers St. 1-13. ea. )831. Nos. 21-26.1830 not been listed. Certain new buildings, which have 621 Broadway. Broadway at Houston Sto John Kellum (N.W. corner], Martin Thompson replaced significant works of architecture, have 59 Macdougal Alley been purposefully omitted. Also commissions for 21 Surrogates Court. 1911 McKim, Mead and White 31 Chembers St. at Centre St. Cu/-de-sac from Macdouga/ St. between interiorsonly, such as shops, banks, and 40 Bayard-Condict Building. -

Leisure Pass Group

Explorer Guidebook Empire State Building Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Advanced reservations are required. You will not be able to enter the Observatory without a timed reservation. Please visit the Empire State Building's website to book a date and time. You will need to have your pass number to hand when making your reservation. Getting in: please arrive with both your Reservation Confirmation and your pass. To gain access to the building, you will be asked to present your Empire State Building reservation confirmation. Your reservation confirmation is not your admission ticket. To gain entry to the Observatory after entering the building, you will need to present your pass for scanning. Please note: In light of COVID-19, we recommend you read the Empire State Building's safety guidelines ahead of your visit. Good to knows: Free high-speed Wi-Fi Eight in-building dining options Signage available in nine languages - English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin Hours of Operation From August: Daily - 11AM-11PM Closings & Holidays Open 365 days a year. Getting There Address 20 West 34th Street (between 5th & 6th Avenue) New York, NY 10118 US Closest Subway Stop 6 train to 33rd Street; R, N, Q, B, D, M, F trains to 34th Street/Herald Square; 1, 2, or 3 trains to 34th Street/Penn Station. The Empire State Building is walking distance from Penn Station, Herald Square, Grand Central Station, and Times Square, less than one block from 34th St subway stop. Top of the Rock Observatory Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Getting In: Use the Rockefeller Plaza entrance on 50th Street (between 5th and 6th Avenues). -

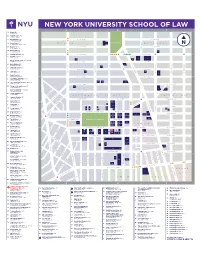

10-0406 NYU Map.Indd

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW 16 Alumni Hall (C-2) 33 3rd Avenue 52 Alumni Relations (B-2) 25 West 4th Street 17 Barney Building (C-2) W. 16TH STREET E. 16TH STREET 34 Stuyvesant Street IRVING PLACE IRVING 60 Bobst Library (B-3) CHELSEA 1 UNION SQUARE GRAMERCY 70 Washington Square South 48 Bookstore (B-2) W. 15TH STREET E. 15TH STREET 18 Washington Place 13 Brittany Hall (B-2) 55 East 10th Street 2 13 Broadway Windows (B-2) W. 14TH STREET E. 14TH STREET 12 Bronfman Center (B-2) 7 East 10th Street 4 3 8 5 Broome Street Residence (not on map) 400 Broome Street W. 13TH STREET E. 13TH STREET THIRD AVENUE 34 Brown Building (B-2) SIXTH AVENUE FIFTH AVENUE UNIVERSITY PLACE BROADWAY AVENUE SECOND AVENUE FIRST 6 FOURTH AVENUE 29 Washington Place 7 26 Cantor Film Center (B-2) 36 East 8th Street W. 12TH STREET E. 12TH STREET 67 Card Center (C-2) 9 14 383 Lafayette Street 15 1 Carlyle Court (B-1) 25 Union Square West W. 11TH STREET E. 11TH STREET 9 Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò (A-1) 24 West 12th Street 11 12 13 80 Coles Sports and Recreation Center (B-3) 181 Mercer Street W. 10TH STREET E. 10TH STREET 32 College of Arts and Science (B-2) 10 33 Washington Place 16 17 College of Dentistry (not on map) 345 East 24th Street W. 9TH STREET E. 9TH STREET 41 College of Nursing (B-2) 726 Broadway STUYVESANT ST. CHARLES ST. GREENWICH VILLAGE EAST VILLAGE 51 Computer Bookstore (B-2) 242 Greene Street W. -

Emergency Response Incidents

Emergency Response Incidents Incident Type Location Borough Utility-Water Main 136-17 72 Avenue Queens Structural-Sidewalk Collapse 927 Broadway Manhattan Utility-Other Manhattan Administration-Other Seagirt Blvd & Beach 9 Street Queens Law Enforcement-Other Brooklyn Utility-Water Main 2-17 54 Avenue Queens Fire-2nd Alarm 238 East 24 Street Manhattan Utility-Water Main 7th Avenue & West 27 Street Manhattan Fire-10-76 (Commercial High Rise Fire) 130 East 57 Street Manhattan Structural-Crane Brooklyn Fire-2nd Alarm 24 Charles Street Manhattan Fire-3rd Alarm 581 3 ave new york Structural-Collapse 55 Thompson St Manhattan Utility-Other Hylan Blvd & Arbutus Avenue Staten Island Fire-2nd Alarm 53-09 Beach Channel Drive Far Rockaway Fire-1st Alarm 151 West 100 Street Manhattan Fire-2nd Alarm 1747 West 6 Street Brooklyn Structural-Crane Brooklyn Structural-Crane 225 Park Avenue South Manhattan Utility-Gas Low Pressure Noble Avenue & Watson Avenue Bronx Page 1 of 478 09/30/2021 Emergency Response Incidents Creation Date Closed Date Latitude Longitude 01/16/2017 01:13:38 PM 40.71400364095638 -73.82998933154158 10/29/2016 12:13:31 PM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 11/22/2016 08:53:17 AM 11/14/2016 03:53:54 PM 40.71400364095638 -73.82998933154158 10/29/2016 05:35:28 PM 12/02/2016 04:40:13 PM 40.71400364095638 -73.82998933154158 11/25/2016 04:06:09 AM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 12/03/2016 04:17:30 AM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 11/26/2016 05:45:43 AM 11/18/2016 01:12:51 PM 12/14/2016 10:26:17 PM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 -

Minutes of the Public Hearing Held on December 9, 1998 at 225

MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES MEETING HELD ON JUNE 3, 2019 AT 105 BROADWAY, SALTAIRE, NEW YORK AND VIA VIDEO/AUDIO LINK TO THE INTERNET TO THE FOLLOWING LOCATIONS WHERE THE RESPECTIVE TRUSTEES WERE LOCATED: Mayor Zaccaro called the Board of Trustees meeting to order at 6:03 p.m., and the following were in attendance: • 218 Lafayette Street, NY, NY John A. Zaccaro Jr, Mayor • 224 Clinton Street, Brooklyn, NY Hillary Richard, Deputy Mayor • 34 Gramercy Park East, #9C, NY, NY Nat Oppenheimer, Trustee • 105 Broadway, Saltaire, NY Frank Wolf, Trustee Hugh O’Brien, Trustee Donna Lyudmer, Village Treasurer Mario Posillico, Administrator & Clerk And 4 other attendees And 11 observed through internet audio/video connection DESIGN DISCUSSION FOR 14 BAY PROMENADE Mayor Zaccaro stated that the primary purpose of the special meeting was to make a final decision on the locations of the four uses within the proposed new structure located at 14 Bay Promenade. He stated that all members of the Board are in agreement regarding the placement of the Post Office and Medical Clinic in the southern quadrants of the building. At issue was the placement of the Public Safety office and the Courtroom in the northern quadrants of the building. He further stated that at the previous design meeting, the Board had requested Village resident and architect Nick Petschek, who had been offering his time to assist Butler Engineering and the Board work through various design decisions and plan iterations during the year-long design process, to do so once again by providing different plan options for the Public Safety office and the Courtroom at each northern quadrant location, specifically showing each one’s placement in both the northwest and northeast quadrants of the building. -

Great Jones Street, 1958 Enamel on Canvas Collection of Irma and Norman Braman

Great Jones Street, 1958 Enamel on canvas Collection of Irma and Norman Braman Yugatan, 1958 Oil and enamel on canvas Private collection Delta, 1958 Enamel on canvas Private collection Jill, 1959 Enamel on canvas Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1962 Die Fahne hoch!, 1959 Enamel on canvas Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene M. Schwartz and purchase with funds from the John I. H. Baur Purchase Fund, the Charles and Anita Blatt Fund, Peter M. Brant, B. H. Friedman, the Gilman Foundation, Inc., Susan Morse Hilles, The Lauder Foundation, Frances and Sydney Lewis, the Albert A. List Fund, Philip Morris Incorporated, Sandra Payson, Mr. and Mrs. Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Percy Uris, Warner Communications Inc., and the National Endowment for the Arts 75.22 Avicenna, 1960 Aluminum oil paint on canvas The Menil Collection, Houston Marquis de Portago (first version), 1960 Aluminum oil paint on canvas Collection of Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Creede I, 1961 Copper oil paint on canvas Collection of Martin Z. Margulies Creede II, 1961 Copper oil paint on canvas Private collection Plant City, 1963 Zinc chromate on canvas Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Agnes Gund in memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, 2008 1 Gran Cairo, 1962 Alkyd on canvas Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art 63.34 Miniature Benjamin Moore series (New Madrid, Sabine Pass, Delaware Crossing, Palmito Ranch, Island No. 10, Hampton Roads), 1962 Alkyd on canvas (Benjamin Moore flat wall paint); six paintings Brooklyn Museum; gift of Andy Warhol 72.167.1–6 Marrakech, 1964 Fluorescent alkyd on canvas The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; gift of Mr.