A Cross-Correlation Technique in Wavelet Domain for Detection of Stochastic Gravitational Waves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 19: Wavelet Compression of Time Series and Images

Lecture 19: Wavelet compression of time series and images c Christopher S. Bretherton Winter 2014 Ref: Matlab Wavelet Toolbox help. 19.1 Wavelet compression of a time series The last section of wavelet leleccum notoolbox.m demonstrates the use of wavelet compression on a time series. The idea is to keep the wavelet coefficients of largest amplitude and zero out the small ones. 19.2 Wavelet analysis/compression of an image Wavelet analysis is easily extended to two-dimensional images or datasets (data matrices), by first doing a wavelet transform of each column of the matrix, then transforming each row of the result (see wavelet image). The wavelet coeffi- cient matrix has the highest level (largest-scale) averages in the first rows/columns, then successively smaller detail scales further down the rows/columns. The ex- ample also shows fine results with 50-fold data compression. 19.3 Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) Given a continuous signal u(t) and an analyzing wavelet (x), the CWT has the form Z 1 s − t W (λ, t) = λ−1=2 ( )u(s)ds (19.3.1) −∞ λ Here λ, the scale, is a continuous variable. We insist that have mean zero and that its square integrates to 1. The continuous Haar wavelet is defined: 8 < 1 0 < t < 1=2 (t) = −1 1=2 < t < 1 (19.3.2) : 0 otherwise W (λ, t) is proportional to the difference of running means of u over successive intervals of length λ/2. 1 Amath 482/582 Lecture 19 Bretherton - Winter 2014 2 In practice, for a discrete time series, the integral is evaluated as a Riemann sum using the Matlab wavelet toolbox function cwt. -

Adaptive Wavelet Clustering for Highly Noisy Data

Adaptive Wavelet Clustering for Highly Noisy Data Zengjian Chen Jiayi Liu Yihe Deng Department of Computer Science Department of Computer Science Department of Mathematics Huazhong University of University of Massachusetts Amherst University of California, Los Angeles Science and Technology Massachusetts, USA California, USA Wuhan, China [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Kun He* John E. Hopcroft Department of Computer Science Department of Computer Science Huazhong University of Science and Technology Cornell University Wuhan, China Ithaca, NY, USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—In this paper we make progress on the unsupervised Based on the pioneering work of Sheikholeslami that applies task of mining arbitrarily shaped clusters in highly noisy datasets, wavelet transform, originally used for signal processing, on which is a task present in many real-world applications. Based spatial data clustering [12], we propose a new wavelet based on the fundamental work that first applies a wavelet transform to data clustering, we propose an adaptive clustering algorithm, algorithm called AdaWave that can adaptively and effectively denoted as AdaWave, which exhibits favorable characteristics for uncover clusters in highly noisy data. To tackle general appli- clustering. By a self-adaptive thresholding technique, AdaWave cations, we assume that the clusters in a dataset do not follow is parameter free and can handle data in various situations. any specific distribution and can be arbitrarily shaped. It is deterministic, fast in linear time, order-insensitive, shape- To show the hardness of the clustering task, we first design insensitive, robust to highly noisy data, and requires no pre- knowledge on data models. -

A Fourier-Wavelet Monte Carlo Method for Fractal Random Fields

JOURNAL OF COMPUTATIONAL PHYSICS 132, 384±408 (1997) ARTICLE NO. CP965647 A Fourier±Wavelet Monte Carlo Method for Fractal Random Fields Frank W. Elliott Jr., David J. Horntrop, and Andrew J. Majda Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, 251 Mercer Street, New York, New York 10012 Received August 2, 1996; revised December 23, 1996 2 2H k[v(x) 2 v(y)] l 5 CHux 2 yu , (1.1) A new hierarchical method for the Monte Carlo simulation of random ®elds called the Fourier±wavelet method is developed and where 0 , H , 1 is the Hurst exponent and k?l denotes applied to isotropic Gaussian random ®elds with power law spectral the expected value. density functions. This technique is based upon the orthogonal Here we develop a new Monte Carlo method based upon decomposition of the Fourier stochastic integral representation of the ®eld using wavelets. The Meyer wavelet is used here because a wavelet expansion of the Fourier space representation of its rapid decay properties allow for a very compact representation the fractal random ®elds in (1.1). This method is capable of the ®eld. The Fourier±wavelet method is shown to be straightfor- of generating a velocity ®eld with the Kolmogoroff spec- ward to implement, given the nature of the necessary precomputa- trum (H 5 Ad in (1.1)) over many (10 to 15) decades of tions and the run-time calculations, and yields comparable results scaling behavior comparable to the physical space multi- with scaling behavior over as many decades as the physical space multiwavelet methods developed recently by two of the authors. -

A Practical Guide to Wavelet Analysis

A Practical Guide to Wavelet Analysis Christopher Torrence and Gilbert P. Compo Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado ABSTRACT A practical step-by-step guide to wavelet analysis is given, with examples taken from time series of the El Niño– Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The guide includes a comparison to the windowed Fourier transform, the choice of an appropriate wavelet basis function, edge effects due to finite-length time series, and the relationship between wavelet scale and Fourier frequency. New statistical significance tests for wavelet power spectra are developed by deriving theo- retical wavelet spectra for white and red noise processes and using these to establish significance levels and confidence intervals. It is shown that smoothing in time or scale can be used to increase the confidence of the wavelet spectrum. Empirical formulas are given for the effect of smoothing on significance levels and confidence intervals. Extensions to wavelet analysis such as filtering, the power Hovmöller, cross-wavelet spectra, and coherence are described. The statistical significance tests are used to give a quantitative measure of changes in ENSO variance on interdecadal timescales. Using new datasets that extend back to 1871, the Niño3 sea surface temperature and the Southern Oscilla- tion index show significantly higher power during 1880–1920 and 1960–90, and lower power during 1920–60, as well as a possible 15-yr modulation of variance. The power Hovmöller of sea level pressure shows significant variations in 2–8-yr wavelet power in both longitude and time. 1. Introduction complete description of geophysical applications can be found in Foufoula-Georgiou and Kumar (1995), Wavelet analysis is becoming a common tool for while a theoretical treatment of wavelet analysis is analyzing localized variations of power within a time given in Daubechies (1992). -

An Overview of Wavelet Transform Concepts and Applications

An overview of wavelet transform concepts and applications Christopher Liner, University of Houston February 26, 2010 Abstract The continuous wavelet transform utilizing a complex Morlet analyzing wavelet has a close connection to the Fourier transform and is a powerful analysis tool for decomposing broadband wavefield data. A wide range of seismic wavelet applications have been reported over the last three decades, and the free Seismic Unix processing system now contains a code (succwt) based on the work reported here. Introduction The continuous wavelet transform (CWT) is one method of investigating the time-frequency details of data whose spectral content varies with time (non-stationary time series). Moti- vation for the CWT can be found in Goupillaud et al. [12], along with a discussion of its relationship to the Fourier and Gabor transforms. As a brief overview, we note that French geophysicist J. Morlet worked with non- stationary time series in the late 1970's to find an alternative to the short-time Fourier transform (STFT). The STFT was known to have poor localization in both time and fre- quency, although it was a first step beyond the standard Fourier transform in the analysis of such data. Morlet's original wavelet transform idea was developed in collaboration with the- oretical physicist A. Grossmann, whose contributions included an exact inversion formula. A series of fundamental papers flowed from this collaboration [16, 12, 13], and connections were soon recognized between Morlet's wavelet transform and earlier methods, including harmonic analysis, scale-space representations, and conjugated quadrature filters. For fur- ther details, the interested reader is referred to Daubechies' [7] account of the early history of the wavelet transform. -

Fourier, Wavelet and Monte Carlo Methods in Computational Finance

Fourier, Wavelet and Monte Carlo Methods in Computational Finance Kees Oosterlee1;2 1CWI, Amsterdam 2Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands AANMPDE-9-16, 7/7/2016 Kees Oosterlee (CWI, TU Delft) Comp. Finance AANMPDE-9-16 1 / 51 Joint work with Fang Fang, Marjon Ruijter, Luis Ortiz, Shashi Jain, Alvaro Leitao, Fei Cong, Qian Feng Agenda Derivatives pricing, Feynman-Kac Theorem Fourier methods Basics of COS method; Basics of SWIFT method; Options with early-exercise features COS method for Bermudan options Monte Carlo method BSDEs, BCOS method (very briefly) Kees Oosterlee (CWI, TU Delft) Comp. Finance AANMPDE-9-16 1 / 51 Agenda Derivatives pricing, Feynman-Kac Theorem Fourier methods Basics of COS method; Basics of SWIFT method; Options with early-exercise features COS method for Bermudan options Monte Carlo method BSDEs, BCOS method (very briefly) Joint work with Fang Fang, Marjon Ruijter, Luis Ortiz, Shashi Jain, Alvaro Leitao, Fei Cong, Qian Feng Kees Oosterlee (CWI, TU Delft) Comp. Finance AANMPDE-9-16 1 / 51 Feynman-Kac theorem: Z T v(t; x) = E g(s; Xs )ds + h(XT ) ; t where Xs is the solution to the FSDE dXs = µ(Xs )ds + σ(Xs )d!s ; Xt = x: Feynman-Kac Theorem The linear partial differential equation: @v(t; x) + Lv(t; x) + g(t; x) = 0; v(T ; x) = h(x); @t with operator 1 Lv(t; x) = µ(x)Dv(t; x) + σ2(x)D2v(t; x): 2 Kees Oosterlee (CWI, TU Delft) Comp. Finance AANMPDE-9-16 2 / 51 Feynman-Kac Theorem The linear partial differential equation: @v(t; x) + Lv(t; x) + g(t; x) = 0; v(T ; x) = h(x); @t with operator 1 Lv(t; x) = µ(x)Dv(t; x) + σ2(x)D2v(t; x): 2 Feynman-Kac theorem: Z T v(t; x) = E g(s; Xs )ds + h(XT ) ; t where Xs is the solution to the FSDE dXs = µ(Xs )ds + σ(Xs )d!s ; Xt = x: Kees Oosterlee (CWI, TU Delft) Comp. -

Wavelet Clustering in Time Series Analysis

Wavelet clustering in time series analysis Carlo Cattani and Armando Ciancio Abstract In this paper we shortly summarize the many advantages of the discrete wavelet transform in the analysis of time series. The data are transformed into clusters of wavelet coefficients and rate of change of the wavelet coefficients, both belonging to a suitable finite dimensional domain. It is shown that the wavelet coefficients are strictly related to the scheme of finite differences, thus giving information on the first and second order properties of the data. In particular, this method is tested on financial data, such as stock pricings, by characterizing the trends and the abrupt changes. The wavelet coefficients projected into the phase space give rise to characteristic cluster which are connected with the volativility of the time series. By their localization they represent a sufficiently good and new estimate of the risk. Mathematics Subject Classification: 35A35, 42C40, 41A15, 47A58; 65T60, 65D07. Key words: Wavelet, Haar function, time series, stock pricing. 1 Introduction In the analysis of time series such as financial data, one of the main task is to con- struct a model able to capture the main features of the data, such as fluctuations, trends, jumps, etc. If the model is both well fitting with the already available data and is expressed by some mathematical relations then it can be temptatively used to forecast the evolution of the time series according to the given model. However, in general any reasonable model depends on an extremely large amount of parameters both deterministic and/or probabilistic [10, 18, 23, 2, 1, 29, 24, 25, 3] implying a com- plex set of complicated mathematical relations. -

Statistical Hypothesis Testing in Wavelet Analysis: Theoretical Developments and Applications to India Rainfall Justin A

Nonlin. Processes Geophys. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/npg-2018-55 Manuscript under review for journal Nonlin. Processes Geophys. Discussion started: 13 December 2018 c Author(s) 2018. CC BY 4.0 License. Statistical Hypothesis Testing in Wavelet Analysis: Theoretical Developments and Applications to India Rainfall Justin A. Schulte1 1Science Systems and Applications, Inc,, Lanham, 20782, United States 5 Correspondence to: Justin A. Schulte ([email protected]) Abstract Statistical hypothesis tests in wavelet analysis are reviewed and developed. The output of a recently developed cumulative area-wise is shown to be the ensemble mean of individual estimates of statistical significance calculated from a geometric test assessing statistical significance based on the area of contiguous regions (i.e. patches) 10 of point-wise significance. This new interpretation is then used to construct a simplified version of the cumulative area-wise test to improve computational efficiency. Ideal examples are used to show that the geometric and cumulative area-wise tests are unable to differentiate features arising from singularity-like structures from those associated with periodicities. A cumulative arc-wise test is therefore developed to test for periodicities in a strict sense. A previously proposed topological significance test is formalized using persistent homology profiles (PHPs) measuring the number 15 of patches and holes corresponding to the set of all point-wise significance values. Ideal examples show that the PHPs can be used to distinguish time series containing signal components from those that are purely noise. To demonstrate the practical uses of the existing and newly developed statistical methodologies, a first comprehensive wavelet analysis of India rainfall is also provided. -

Wavelet Cross-Correlation Analysis of Wind Speed Series Generated by ANN Based Models Grégory Turbelin, Pierre Ngae, Michel Grignon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication Wavelet cross-correlation analysis of wind speed series generated by ANN based models Grégory Turbelin, Pierre Ngae, Michel Grignon To cite this version: Grégory Turbelin, Pierre Ngae, Michel Grignon. Wavelet cross-correlation analysis of wind speed series generated by ANN based models. Renewable Energy, Elsevier, 2009, 34, 4, pp.1024–1032. 10.1016/j.renene.2008.08.016. hal-01178999 HAL Id: hal-01178999 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01178999 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Wavelet cross correlation analysis of wind speed series generated by ANN based models Grégory Turbelin*, Pierre Ngae, Michel Grignon Laboratoire de Mécanique et d’Energétique d’Evry (LMEE),Université d’Evry Val d’Essonne 40 rue du Pelvoux, 91020 Evry Cedex, France Abstract To obtain, over medium term periods, wind speed time series on a site, located in the southern part of the Paris region (France), where long recording are not available, but where nearby meteorological stations provide large series of data, use was made of ANN based models. -

Wavelets, Their Autocorrelation Functions, and Multiresolution Representation of Signals

Wavelets, their autocorrelation functions, and multiresolution representation of signals Gregory Beylkin University of Colorado at Boulder, Program in Applied Mathematics Boulder, CO 80309-0526 Naoki Saito 1 Schlumberger–Doll Research Old Quarry Road, Ridgefield, CT 06877-4108 ABSTRACT We summarize the properties of the auto-correlation functions of compactly supported wavelets, their connection to iterative interpolation schemes, and the use of these functions for multiresolution analysis of signals. We briefly describe properties of representations using dilations and translations of these auto- correlation functions (the auto-correlation shell) which permit multiresolution analysis of signals. 1. WAVELETS AND THEIR AUTOCORRELATION FUNCTIONS The auto-correlation functions of compactly supported scaling functions were first studied in the context of the Lagrange iterative interpolation scheme in [6], [5]. Let Φ(x) be the auto-correlation function, +∞ Φ(x)= ϕ(y)ϕ(y x)dy, (1.1) Z−∞ − where ϕ(x) is the scaling function which appears in the construction of compactly supported wavelets in [3]. The function Φ(x) is exactly the “fundamental function” of the symmetric iterative interpolation scheme introduced in [6], [5]. Thus, there is a simple one-to-one correspondence between iterative interpolation schemes and compactly supported wavelets [12], [11]. In particular, the scaling function corresponding to Daubechies’s wavelet with two vanishing moments yields the scheme in [6]. In general, the scaling functions corresponding to Daubechies’s wavelets with M vanishing moments lead to the iterative interpolation schemes which use the Lagrange polynomials of degree 2M [5]. Additional variants of iterative interpolation schemes may be obtained using compactly supported wavelets described in [4]. -

The Wavelet Tutorial Second Edition Part I by Robi Polikar

THE WAVELET TUTORIAL SECOND EDITION PART I BY ROBI POLIKAR FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS & AN OVERVIEW OF THE WAVELET THEORY Welcome to this introductory tutorial on wavelet transforms. The wavelet transform is a relatively new concept (about 10 years old), but yet there are quite a few articles and books written on them. However, most of these books and articles are written by math people, for the other math people; still most of the math people don't know what the other math people are 1 talking about (a math professor of mine made this confession). In other words, majority of the literature available on wavelet transforms are of little help, if any, to those who are new to this subject (this is my personal opinion). When I first started working on wavelet transforms I have struggled for many hours and days to figure out what was going on in this mysterious world of wavelet transforms, due to the lack of introductory level text(s) in this subject. Therefore, I have decided to write this tutorial for the ones who are new to the topic. I consider myself quite new to the subject too, and I have to confess that I have not figured out all the theoretical details yet. However, as far as the engineering applications are concerned, I think all the theoretical details are not necessarily necessary (!). In this tutorial I will try to give basic principles underlying the wavelet theory. The proofs of the theorems and related equations will not be given in this tutorial due to the simple assumption that the intended readers of this tutorial do not need them at this time. -

Wavelets T( )= T( ) G F( ) F ,T ( )D F

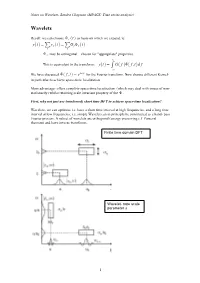

Notes on Wavelets- Sandra Chapman (MPAGS: Time series analysis) Wavelets Recall: we can choose ! f (t ) as basis on which we expand, ie: y(t ) = " y f (t ) = "G f ! f (t ) f f ! f may be orthogonal – chosen for "appropriate" properties. # This is equivalent to the transform: y(t ) = $ G( f )!( f ,t )d f "# We have discussed !( f ,t ) = e2!ift for the Fourier transform. Now choose different Kernel- in particular to achieve space-time localization. Main advantage- offers complete space-time localization (which may deal with issues of non- stationarity) whilst retaining scale invariant property of the ! . First, why not just use (windowed) short time DFT to achieve space-time localization? Wavelets- we can optimize i.e. have a short time interval at high frequencies, and a long time interval at low frequencies; i.e. simple Wavelet can in principle be constructed as a band- pass Fourier process. A subset of wavelets are orthogonal (energy preserving c.f Parseval theorem) and have inverse transforms. Finite time domain DFT Wavelet- note scale parameter s 1 Notes on Wavelets- Sandra Chapman (MPAGS: Time series analysis) So at its simplest, a wavelet transform is simply a collection of windowed band pass filters applied to the Fourier transform- and this is how wavelet transforms are often computed (as in Matlab). However we will want to impose some desirable properties, invertability (orthogonality) and completeness. Continuous Fourier transform: " m 1 T / 2 2!ifmt !2!ifmt x(t ) = Sme , fm = Sm = x(t )e dt # "!T / 2 m=!" T T ! i( n!m)x with orthogonality: e dx = 2!"mn "!! " x(t ) = # S( f )e2!ift df continuous Fourier transform pair: !" " S( f ) = # x(t )e!2!ift dt !" Continuous Wavelet transform: $ W !,a = x t " * t dt ( ) % ( ) ! ,a ( ) #$ 1 $ & $ ) da x(t) = ( W (!,a)"! ! ,a d! + 2 C % % a " 0 '#$ * 1 $ t # " ' Where the mother wavelet is ! " ,a (t) = ! & ) where ! is the shift parameter and a a % a ( is the scale (dilation) parameter (we can generalize to have a scaling function a(t)).