Look Toward the Mountain, Episode 2 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Investigations 2008

Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Investigations 2008 Report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team Photo courtesy of Steve Ard Data contained in this report are preliminary and subject to change. Please obtain permission prior to citation. To give credit to authors, please cite the section within this report as a chapter in a book. Below is an example: Moody, D.S., K. Frey, and D. Meints. 2009. Trends in elk hunter numbers within the Primary Conservation Area plus the 10-mile perimeter area. Page 39 in C.C. Schwartz, M.A. Haroldson, and K. West, editors. Yellowstone grizzly bear investigations: annual report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, 2008. U.S. Geological Survey, Bozeman, Montana, USA. Cover: Female #533 with her 3 3-year-old offspring after den emergence, taken 1 May 2008 by Steve Ard. YELLOWSTONE GRIZZLY BEAR INVESTIGATIONS Annual Report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team 2008 U.S. Geological Survey Wyoming Game and Fish Department National Park Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks U.S. Forest Service Idaho Department of Fish and Game Edited by Charles C. Schwartz, Mark A. Haroldson, and Karrie West U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey 2009 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 This Report ............................................................................................................................................ -

Mountain Man Clymer Museum of Art It Has Been Said That It Took Rugged, Practically Fearless Individuals to Explore and Settle America’S West

HHiiSSTORTORYY— PaSt aNd PerspeCtive John Colter encountering some Indians The First Mountain Man Clymer Museum of Art It has been said that it took rugged, practically fearless individuals to explore and settle America’s West. Surely few would live up to such a characterization as well as John Colter. by Charles Scaliger ran, and sharp stones gouged the soles of wether Lewis traveled down the Ohio his feet, but he paid the pain no mind; any River recruiting men for his Corps of Dis- he sinewy, bearded man raced up torment was preferable to what the Black- covery, which was about to strike out on the brushy hillside, blood stream- foot warriors would inflict on him if they its fabled journey across the continent to ing from his nose from the terrific captured him again. map and explore. The qualifications for re- Texertion. He did not consider himself a cruits were very specific; enlistees in what In 1808, the year John Colter ran his fast runner, but on this occasion the terror race with the Blackfeet, Western Mon- became known as the Lewis and Clark of sudden and agonizing death lent wings tana had been seen by only a handful of expedition had to be “good hunter[s], to his feet. Somewhere not far behind, his white men. The better-known era of the stout, healthy, unmarried, accustomed to pursuers, their lean bodies more accus- Old West, with its gunfighters, cattlemen, the woods, and capable of bearing bodily tomed than his to the severe terrain, were and mining towns, lay decades in the fu- fatigue in a pretty considerable degree.” closing in, determined to avenge the death ture. -

Secondary Carbonate Accumulations in Soils of the Baikal Region: Formation Processes and Significance for Paleosoil Investigations

Вестник Томского государственного университета. Биология. 2017. № 39. С. 6–28 АГРОХИМИЯ И ПОЧВОВЕДЕНИЕ УДК 631.48 (571.5) doi: 10.17223/19988591/39/1 В.А. Голубцов Институт географии им. В.Б. Сочавы СО РАН, г. Иркутск, Россия Карбонатные новообразования в почвах Байкальского региона: процессы формирования и значение для палеопочвенных исследований Работа выполнена при поддержке РФФИ (проект № 17-04-00092). На данный момент вопросы, касающиеся строения, хронологии и специфики формирования педогенных карбонатов в резкоконтинентальных областях юга Восточной Сибири, остаются практически незатронутыми. Выполнено обобщение сформировавшихся за последние годы представлений о механизмах формирования карбонатных новообразований почв, а также их связи с условиями среды и процессами почвообразования. Оценены пути поступления карбонатов и основные факторы их аккумуляции в профиле почв. Описаны особенности вещественного и изотопного состава карбонатных новообразований в почвах, формирующихся в различных климатических условиях. На основании собственных исследований приводятся данные о разнообразии карбонатных аккумуляций в почвах Байкальского региона, их вещественном составе и роли в качестве палеогеографических индикаторов. Детально рассмотрены следующие формы карбонатных новообразований: ризолиты, игольчатый кальцит, гипокутаны, белоглазка, нодули, кутаны, лессовые куколки. Ключевые слова: карбонаты; педогенные карбонатные новообразования; стабильные изотопы; почвы; палеореконструкции. Введение Первостепенное значение при изучении эволюции почв имеет -

Celebrating 100 Years ■ 2018 Bierstadt Exhibition

fall & winter 2017 Celebrating100 years ■ 2018 Bierstadt exhibition ■ From Thorofare to destination, part 2 ■ Dispatches from the Field: the eagles of Rattlesnake Gulch to the point BY BRUCE ELDREDGE | Executive Director About the cover: In Irving R. Bacon’s (1875 – 1962) Cody on the Ishawooa Trail, 1904, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody is either gauging the trail before him, or assessing the miles he left behind. As the Buffalo Bill Center of the West nears the end of its Centennial year, we find ourselves on an Ishawooa Trail of our own—celebrating and appraising the past while we plan for the next hundred years. #100YearsMore ©2017 Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Points West is published for members and friends of the Center of the West. Written permission is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials in any medium or format. All photographs in Points West are Center of the West photos unless otherwise noted. Direct all questions about image rights and reproduction to [email protected]. Bibliographies, works cited, and footnotes, etc. are purposely omitted to conserve space. However, such information is available by contacting the editor. Address correspondence to Editor, Points West, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, As we near the end of 2017, it’s hard to believe our Centennial is soon to become 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody, Wyoming 82414, or a memory! We’ve had a great celebratory year filled with people and tales about [email protected]. our first hundred years. Exploring our history in depth these past few months has truly validated the words of Henry Ford, who said, “Coming together is a beginning; ■ Managing Editor | Marguerite House keeping together is progress; working together is success.” ■ Assistant Editor | Nancy McClure The Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s beginning was the coming together in ■ Designer | Desirée Pettet & Jessica McKibben 1917 of the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association (BBMA) to honor their namesake and ■ preserve the Spirit of the American West. -

Common Birds of the Brinton Museum and Bighorn Mountains Foothills

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 8-9-2017 Common Birds of The rB inton Museum and Bighorn Mountains Foothills Jackie Canterbury University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Paul Johnsgard University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Canterbury, Jackie and Johnsgard, Paul, "Common Birds of The rB inton Museum and Bighorn Mountains Foothills" (2017). Zea E- Books. 57. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/57 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Common Birds of The Brinton Museum and Bighorn Mountains Foothills Jacqueline L. Canterbury & Paul A. Johnsgard Jacqueline L. Canterbury acquired a passion for birds and conservation in college, earning bachelor’s degrees at the University of Washington and Evergreen State Col- lege plus MS and PhD degrees from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln with an em- phasis in physiology and neuroscience. Her master’s degree program involved de- veloping a conservation strategy for nongame birds for the state of Nebraska, and she worked for several years as a US Forest Service biologist, studying bird popula- tions in the Tongass National Forest in southeast Alaska. She is currently president of the Bighorn Audubon Society chapter in Sheridan, Wyoming, working on estab- lishing regional Important Bird Areas (IBAs). -

What in the World Fall/Winter 2011-2012 Newsletter Geography Awarness Week Pg

In This Issue: Letter from the Chair Pg. 1 What in the World Fall/Winter 2011-2012 Newsletter Geography Awarness Week Pg. 2 “Geography is a Field Discipline” Pg. 2 Letter from the Chair National Geographic Internship Pg. 3 Dear Alumni and Friends of Geography Notably, Caroline McClure completed a at the Univeristy of Wyoming, NGS internship during the spring semester Regional AAG Meeting in Denver Pg. 3 2011 (see page 3). Awards and Recognitions Pg. 4 Greetings from Laramie and the Department The graduate program in geography at UW of Geography at the University of Wyoming! is also thriving. This year eleven new MA UW Geographers in Ethiopia Pg. 5 As you will see while reading this students joined the program coming from newsletter, the Department Donor Challenge Pg. 6 around the United States of Geography at UW and world. We have two Recent Faculty Publications Pg. 7 continues to be active new students from Nepal, in its teaching, research and another from Thailand. Faculty Highlights Pg. 8 and service missions. Additionally, students from We are fortunate to have Michigan, Illinois, Colorado Heart Mountain Pg. 9 a dedicated faculty, and Oklahoma as well knowledgeable staff and as Wyoming joined our great students. Confirming departmental community. this statement is the number A new class of this size and of awards and recognitions diversity is a testament to received over the past few the quality of our faculty months by our departmental and their willingness to community. develop strong mentoring relationships with our Last spring three of our incoming students. We graduate students, Richard are currently reviewing Vercoe, Suzette Savoie, applications for next year, and Alexa Dugan, were Professor and Chair, Gerald R. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Honor among Thieves: Horse Stealing, State-Building, and Culture in Lincoln County, Nebraska, 1860 - 1890 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1h33n2hw Author Luckett, Matthew S Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Honor among Thieves: Horse Stealing, State-Building, and Culture in Lincoln County, Nebraska, 1860 – 1890 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Matthew S Luckett 2014 © Copyright by Matthew S Luckett 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Honor among Thieves: Horse Stealing, State-Building, and Culture in Lincoln County, Nebraska, 1860 – 1890 by Matthew S Luckett Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Stephen A. Aron, Chair This dissertation explores the social, cultural, and economic history of horse stealing among both American Indians and Euro Americans in Lincoln County, Nebraska from 1860 to 1890. It shows how American Indians and Euro-Americans stole from one another during the Plains Indian Wars and explains how a culture of theft prevailed throughout the region until the late-1870s. But as homesteaders flooded into Lincoln County during the 1870s and 1880s, they demanded that the state help protect their private property. These demands encouraged state building efforts in the region, which in turn drove horse stealing – and the thieves themselves – underground. However, when newspapers and local leaders questioned the efficacy of these efforts, citizens took extralegal steps to secure private property and augment, or subvert, the law. -

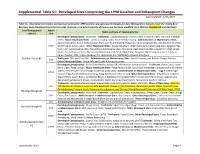

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015 Table S1. Developed sites (name and type) comprising the 1998 baseline and subsequent changes per Bear Management Subunit inside the Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone (Developed sites that are new, removed, or in which capacity of human-use has been modified since 1998 are highlighted and italicized). Bear Management Admin Name and type of developed sites subunit Unit Developed Campgrounds: Cave Falls. Trailheads: Coyote Meadows, Hominy Peak, S. Boone Creek, Fish Lake, Cascade Creek. Major Developed Sites: Loll Scout Camp, Idaho Youth Services Camp. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Squirrel Meadows Guard Station/Cabin, Porcupine Guard Station, Badger Creek Seismograph Site, and Squirrel Meadows CTNF GS/WY Game & Fish Cabin. Other Developed Sites: Grassy Lake Dam, Tillery Lake Dam, Indian Lake Dam, Bergman Res. Dam, Loon Lake Disperse sites, Horseshoe Lake Disperse sites, Porcupine Creek Disperse sites, Gravel Pit/Target Range, Boone Creek Disperse Sites, Tillery Lake O&G Camp, Calf Creek O&G Camp, Bergman O&G Camp, Granite Creek Cow Camp, Poacher’s TH, Indian Meadows TH, McRenolds Res. TH/Wildlife Viewing Area/Dam. Bechler/Teton #1 Trailheads: 9K1 and Cave Falls. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: South Entrance and Bechler Ranger Stations. YNP Other Developed Sites: Union Falls and Snake River picnic areas. Developed Campgrounds: Grassy Lake Road campsites (8 individual car camping sites). Trailheads: Glade Creek, Lower Berry Creek, Flagg Canyon. Major Developed Sites: Flagg Ranch (lodge, cabins and Headwater Campground with camper cabins, remote cistern and sewage treatment plant sites). Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Flagg Ranch Ranger GTNP Station, Flagg Ranch employee housing, Flagg Ranch maintenance yard. -

This Is a Digital Document from the Collections of the Wyoming Water Resources Data System (WRDS) Library

This is a digital document from the collections of the Wyoming Water Resources Data System (WRDS) Library. For additional information about this document and the document conversion process, please contact WRDS at [email protected] and include the phrase “Digital Documents” in your subject heading. To view other documents please visit the WRDS Library online at: http://library.wrds.uwyo.edu Mailing Address: Water Resources Data System University of Wyoming, Dept 3943 1000 E University Avenue Laramie, WY 82071 Physical Address: Wyoming Hall, Room 249 University of Wyoming Laramie, WY 82071 Phone: (307) 766-6651 Fax: (307) 766-3785 Funding for WRDS and the creation of this electronic document was provided by the Wyoming Water Development Commission (http://wwdc.state.wy.us) VOLUME 11-A OCCURRENCE AND CHARACTERISTICS OF GROUND WATER IN THE BIGHORN BASIN, WYOMING Robert Libra, Dale Doremus , Craig Goodwin Project Manager Craig Eisen Water Resources Research Institute University of Wyoming Report to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Contract Number G 008269-791 Project Officer Paul Osborne June, 1981 INTRODUCTION This report is the second of a series of hydrogeologic basin reports that define the occurrence and chemical quality of ground water within Wyoming. Information presented in this report has been obtained from several sources including available U.S. Geological Survey publications, the Wyoming State Engineer's Office, the Wyoming Geological Survey, and the Wyoming Oil and Gas Conservation Commission. The purpose of this report is to provide background information for implementation of the Underground Injection Control Program (UIC). The UIC program, authorized by the Safe Drinking Water Act (P.L. -

13Th Bighorn Mountains

13TH BIGHORN MOUNTAINS BURGESS JUNCTION, WYOMING • AUGUST 26 - 28, 2021 TRAIL RATING 3 - 7 Policies & Reminders For All 2021 Jeep Jamborees Event Waiver Follow The Flow • You are required to complete a Release of Liability When you arrive at a Jeep Jamboree, you Waiver for all occupants of your Jeep 4x4. You must must complete these steps in this order: bring it with you to on-site registration. Vehicle Evaluation Registration Trail Sign-Up • A printed, signed, and dated Release of You will not be permitted sign-up for trails until you have Liability Waiver is required for each participant completed Vehicle Evaluation and Registration. attending a Jeep Jamboree USA event. • All passengers in your Jeep 4x4 must sign a Name Badge Release of Liability Waiver. A parent or the Each participant must wear their name badge throughout minor’s legal guardian must sign and date a the entire Jamboree. waiver for participants under the age of 18 years old. • If you forget your signed Release of Liability Waiver, all Trail Stickers occupants of your vehicle must be present at registration Trail stickers provided at trail sign-ups must be displayed to sign a new waiver before you can receive your on your windshield prior to departing for any off-road event credentials. trail ride. On-Site Registrations Will Not Be Accepted Trail Conditions All new registrations of vehicles as well as adding, deleting, Trail conditions can vary widely between trails and or changing passengers must be completed (10) ten days even on the same trail on different days. Factors such as prior to the Jamboree date. -

2021 Adventure Vacation Guide Cody Yellowstone Adventure Vacation Guide 3

2021 ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE CODY YELLOWSTONE ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE 3 WELCOME TO THE GREAT AMERICAN ADVENTURE. The West isn’t just a direction. It’s not just a mark on a map or a point on a compass. The West is our heritage and our soul. It’s our parents and our grandparents. It’s the explorers and trailblazers and outlaws who came before us. And the proud people who were here before them. It’s the adventurous spirit that forged the American character. It’s wide-open spaces that dare us to dream audacious dreams. And grand mountains that make us feel smaller and bigger all at the same time. It’s a thump in your chest the first time you stand face to face with a buffalo. And a swelling of pride that a place like this still exists. It’s everything great about America. And it still flows through our veins. Some people say it’s vanishing. But we say it never will. It will live as long as there are people who still live by its code and safeguard its wonders. It will live as long as there are places like Yellowstone and towns like Cody, Wyoming. Because we are blood brothers, Yellowstone and Cody. One and the same. This is where the Great American Adventure calls home. And if you listen closely, you can hear it calling you. 4 CODYYELLOWSTONE.ORG CODY YELLOWSTONE ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE 5 William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody with eight Native American members of the cast of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, HISTORY ca. -

Oreohelix Land Snails of Heart Mountain Ranch and Tensleep Preserve, Wyoming

Oreohelix land snails of Heart Mountain Ranch and Tensleep Preserve, Wyoming April 2011 Prepared by: Lusha Tronstad Invertebrate Zoologist Wyoming Natural Diversity Database University of Wyoming Laramie, Wyoming 82071 Tele: 307-766-3115 Email: [email protected] Prepared for: Katherine Thompson, Program Director Northwest Wyoming Program of The Nature Conservancy 1128 12th Street, Suite A Cody, Wyoming 82414 Tele: 307-587-1655 Email: [email protected] Suggested citation: Tronstad, L.M. 2011. Oreohelix land snails of Heart Mountain Ranch and Tensleep Preserve, Wyoming. Prepared by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming for The Nature Conservancy. Mountain snails (Oreohelix sp.) are generally considered rare. In fact, Oreohelix peripherica wasatchensis is a candidate species in Utah under the Endangered Species Act, and several species of Oreohelix are considered critically imperiled by NatureServe. In Wyoming, Oreohelix pygmaea is an endemic species (only found in Wyoming) that lives in the Bighorn Mountains. Another species being watched in Wyoming and South Dakota is Oreohelix strigosa cooperi (referred to as Oreohelix cooperi by some), which is only found in the Black Hills and was petitioned for listing under the Endangered Species Act in 2006, but not listed. Oreohelix are relatively large land snails, but little is known about this genus. As their common names suggests, mountain snails live in mountainous regions of western North America. These land snails are active during wet, cool mouths of the year (i.e., early summer). Oreohelix carry their young internally until they are born at ~2.5 whorls. Mountain snails are one of the more obvious land snail genera, because of their large shell size (10-20 mm diameter).