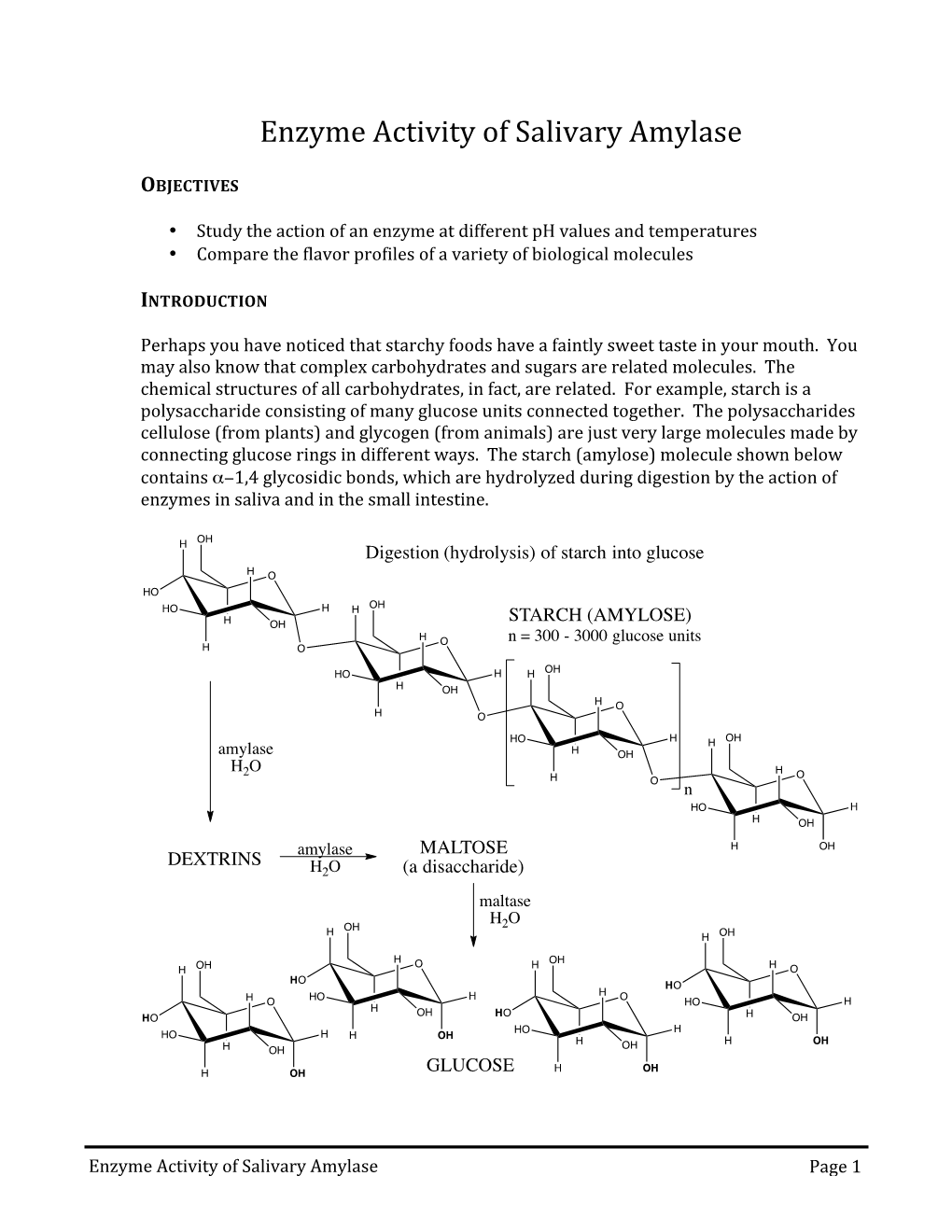

Enzyme Activity of Salivary Amylase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Glossary for AQA GCSE Biology Student Book

Biology Glossary amino acids small molecules from which proteins are A built abiotic factor physical or non-living conditions amylase a digestive enzyme (carbohydrase) that that affect the distribution of a population in an breaks down starch ecosystem, such as light, temperature, soil pH anaerobic respiration respiration without using absorption the process by which soluble products oxygen of digestion move into the blood from the small intestine antibacterial chemicals chemicals produced by plants as a defence mechanism; the amount abstinence method of contraception whereby the produced will increase if the plant is under attack couple refrains from intercourse, particularly when an egg might be in the oviduct antibiotic e.g. penicillin; medicines that work inside the body to kill bacterial pathogens accommodation ability of the eyes to change focus antibody protein normally present in the body acid rain rain water which is made more acidic by or produced in response to an antigen, which it pollutant gases neutralises, thus producing an immune response active site the place on an enzyme where the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) an increasing substrate molecule binds problem in the twenty-first century whereby active transport in active transport, cells use energy bacteria have evolved to develop resistance against to transport substances through cell membranes antibiotics due to their overuse against a concentration gradient antiretroviral drugs drugs used to treat HIV adaptation features that organisms have to help infections; they -

NADPH-Dependent A-Oxidation of Unsaturated Fatty Acids With

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 89, pp. 6673-6677, August 1992 Biochemistry NADPH-dependent a-oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids with double bonds extending from odd-numbered carbon atoms (5-enoyl-CoA/A3,A2-enoyl-CoA isomerase/A3',52'4-dienoyl-CoA isomerase/2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase) TOR E. SMELAND*, MOHAMED NADA*, DEAN CUEBASt, AND HORST SCHULZ* *Department of Chemistry, City College of the City University of New York, New York, NY 10031; and tJoined Departments of Chemistry, Manhattan College/College of Mount Saint Vincent, Riverdale, NY 10471 Communicated by Salih J. Wakil, April 13, 1992 ABSTRACT The mitochondrial metabolism of 5-enoyl- a recent observation of Tserng and Jin (5) who reported that CoAs, which are formed during the (3-oxidation of unsaturated the mitochondrial -oxidation of 5-enoyl-CoAs is dependent fatty acids with double bonds extending from odd-numbered on NADPH. Their analysis of metabolites by gas chroma- carbon atoms, was studied with mitochondrial extracts and tography/mass spectrometry led them to propose that the purified enzymes of (3-oxidation. Metabolites were identified double bond of 5-enoyl-CoAs is reduced by NADPH to yield spectrophotometrically and by high performance liquid chro- the corresponding saturated fatty acyl-CoAs, which are then matography. 5-cis-Octenoyl-CoA, a putative metabolite of further degraded by P-oxidation. linolenic acid, was efficiently dehydrogenated by medium- This report addresses the question of how 5-enoyl-CoAs chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (EC 1.3.99.3) to 2-trans-5-cis- are chain-shortened by P-oxidation. We demonstrate that octadienoyl-CoA, which was isomerized to 3,5-octadienoyl- 5-enoyl-CoAs, after dehydrogenation to 2,5-dienoyl-CoAs, CoA either by mitochondrial A3,A2-enoyl-CoA isomerase (EC can be isomerized to 2,4-dienoyl-CoAs, which are reduced by 5.3.3.8) or by peroxisomal trifunctional enzyme. -

Chapter 7. "Coenzymes and Vitamins" Reading Assignment

Chapter 7. "Coenzymes and Vitamins" Reading Assignment: pp. 192-202, 207-208, 212-214 Problem Assignment: 3, 4, & 7 I. Introduction Many complex metabolic reactions cannot be carried out using only the chemical mechanisms available to the side-chains of the 20 standard amino acids. To perform these reactions, enzymes must rely on other chemical species known broadly as cofactors that bind to the active site and assist in the reaction mechanism. An enzyme lacking its cofactor is referred to as an apoenzyme whereas the enzyme with its cofactor is referred to as a holoenzyme. Cofactors are subdivided into essential ions and organic molecules known as coenzymes (Fig. 7.1). Essential ions, commonly metal ions, may participate in substrate binding or directly in the catalytic mechanism. Coenzymes typically act as group transfer agents, carrying electrons and chemical groups such as acyl groups, methyl groups, etc., depending on the coenzyme. Many of the coenzymes are derived from vitamins which are essential for metabolism, growth, and development. We will use this chapter to introduce all of the vitamins and coenzymes. In a few cases--NAD+, FAD, coenzyme A--the mechanisms of action will be covered. For the remainder of the water-soluble vitamins, discussion of function will be delayed until we encounter them in metabolism. We also will discuss the biochemistry of the fat-soluble vitamins here. II. Inorganic cation cofactors Many enzymes require metal cations for activity. Metal-activated enzymes require or are stimulated by cations such as K+, Ca2+, or Mg2+. Often the metal ion is not tightly bound and may even be carried into the active site attached to a substrate, as occurs in the case of kinases whose actual substrate is a magnesium-ATP complex. -

Enzymes Main Concepts: •Proteins Are Polymers Made up of Amino Acids

Biology 102 Karen Bledsoe, Instructor Notes http://www.wou.edu/~bledsoek/ Chapter 6, section 4 Topic: Enzymes Main concepts: • Proteins are polymers made up of amino acids. Enzymes are a category of proteins. • Enzymes are catalysts. They speed up the rate of a chemical reaction by reducing the activation energy, which is the energy needed to carry out the reaction. An example of a catalyst: if you put a lit match to a sugar cube, it’s hard to make the sugar catch fire. But if you rub a corner of the sugar cube with ash or charcoal, it catches more easily. The ash or charcoal acts as a catalyst. • Many important chemical reactions in living cells can happen spontaneously, but these reactions happen too rarely and too slowly to sustain life. Enzymes make the reactions happen more quickly and more often. • Some reactions happen too violently to support life. Sugar, when burned, released a lot of energy, but the energy is mostly heat. A rapid reaction like that would overheat our cells. Enzyme-controlled reactions can release energy from sugar in a way that captures most of the energy and loses less of the energy as heat, so that the energy is useful to the cell and does not overheat the cell. • The structure of enzymes allows them to carry out reactions. Each enzyme is shaped to carry out only one specific reaction. This is known as enzyme specificity. Amylase, for example, is an enzyme that breaks down starch into glucose. Amylase only breaks down starch; it does not break down any other molecule, nor does it build starch out of glucose. -

Digestive Enzyme: Amylase

DIGESTIVE ENZYME: AMYLASE BACKGROUND Caution: Most animals begin their digestion in their mouths. Chewing breaks up Lugol’s solution is slightly large pieces of food and chemicals in the saliva begin breaking apart hazardous: molecules of starch. In this experiment we add saliva to crackers to • It should not be observe the how quickly this process begins to happen. handled by small children. Basic definitions: • It is dangerous if Amylase: an enzyme that breaks down starch into sugars. swallowed. Enzyme: a protein that speeds up a chemical reaction. • Participants should Chemical Indicator: a chemical that allows you to observe that a wear gloves. reaction has taken place. • Adults should place Starch: a complex arrangement of sugar molecules. the Lugol’s solution into a small dropper Starch is a long group of glucose (sugar) molecules bonded together. bottle for youth to Amylose is the starch form that’s found in crackers. In amylose, the use. sugar molecules form a structure that has small spaces in between the molecules of sugar. Lugol’s solution contains iodine molecules that fit Skills: tightly inside these small spaces. When the iodine molecules are inside • Observation, these small spaces between bonded sugar molecules, the iodine looks teamwork. blue-black in color. If the sugar molecules begin to break apart and release the iodine molecules, the indicator solution looks light brown- Grade Levels: Grades 4 - brown in color. 12 Amylase is the protein that breaks apart starch into sugars. Amylase is a • Time: 15 – 20 minutes chemical found in the saliva of many animals. Number of Youth: Materials for each test group: Any Lugol’s Solution (2%) in small dropper bottle 2 test tubes with lids : 25ml or 50 ml Supplies Needed: Small cup of water Materials for each test Crushed saltine cracker in zip lock bag group: 5-7 plastic cups: 3 oz. -

The Role of Phospholipase D (Pld) and Grb2 in Chemotaxis

THE ROLE OF PHOSPHOLIPASE D (PLD) AND GRB2 IN CHEMOTAXIS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science By KATIE J. KNAPEK B.S., Indiana University of Pennyslvania, 2006 2008 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES December 19, 2008 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISON BY Katie J. Knapek ENTITLED The Role of Phospholipase D (PLD) and Grb2 in Chemotaxis BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science. _____________________________ Julian Gomez-Cambronero, Ph. D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Barbara Hull, Ph. D. Program Director Committee on Final Examination _______________________ Julian Gomez-Cambronero, Ph. D. _______________________ Nancy Bigley, Ph. D. _______________________ Mill Miller, Ph. D. ________________________ Joseph F. Thomas Jr., Ph. D. Dean, School of Graduate Studies ABSTRACT Knapek, Katie J. M.S., Department of Biological Sciences, Microbiology and Immunology Program, Wright State University, 2008. The Role of Phospholipase D (PLD) and Grb2 in Chemotaxis. Phospholipase D (PLD) is an enzyme that hydrolyzes phosphatidylcholine yielding choline and phosphatidic acid. PLD is activated by mitogens (lead to cell division) and motogens (leading to cell migration). PLD is known to contribute to cellular proliferation and deregulated expression of PLD has been implicated in several human cancers. PLD has been found to play a role in leukocyte chemotaxis and adhesion as studied through the formation of chemokine gradients. We have established a model of cell migration comprising three cell lines: macrophages RAW 264.7 and LR-5 (for innate defense), and fibroblast COS-7 cells (for wound healing). -

Enhancement in Phospholipase D Activity As a New Proposed Molecular Mechanism of Haloperidol-Induced Neurotoxicity

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Communication Enhancement in Phospholipase D Activity as a New Proposed Molecular Mechanism of Haloperidol-Induced Neurotoxicity Marek Krzystanek 1,*, Ewa Krzystanek 2 , Katarzyna Skałacka 3 and Artur Pałasz 4 1 Department and Clinic of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Medical School of Silesia in Katowice, Ziołowa 45/47, 40-635 Katowice, Poland 2 Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Medical School of Silesia in Katowice, Medyków 14, 40-772 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] 3 Institute of Psychology, University of Opole, Kopernika 11A Street, 45-040 Opole, Poland; [email protected] 4 Department of Histology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Medical School of Silesia in Katowice, Medyków 18, 40-752 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 19 November 2020; Accepted: 1 December 2020; Published: 4 December 2020 Abstract: Membrane phospholipase D (PLD) is associated with numerous neuronal functions, such as axonal growth, synaptogenesis, formation of secretory vesicles, neurodegeneration, and apoptosis. PLD acts mainly on phosphatidylcholine, from which phosphatidic acid (PA) and choline are formed. In turn, PA is a key element of the PLD-dependent secondary messenger system. Changes in PLD activity are associated with the mechanism of action of olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic. The aim of the present study was to assess the effect of short-term administration of the first-generation antipsychotic drugs haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and fluphenazine on membrane PLD activity in the rat brain. Animals were sacrificed for a time equal to the half-life of the antipsychotic drug in the brain, then the membranes in which PLD activity was determined were isolated from the tissue. -

Enzyme Preparations: Recommendations for Submission of Chemical and Technological Data for Food Additive Petitions and GRAS Notices

Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Guidance for Industry Enzyme Preparations: Recommendations for Submission of Chemical and Technological Data for Food Additive Petitions and GRAS Notices Additional copies are available from: Office of Food Additive Safety Division of Biotechnology and GRAS Notice Review, HFS-255 Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Food and Drug Administration 5001 Campus Drive College Park, MD 20740 (Tel) 301-436-1200 http://www.fda.gov/FoodGuidances You may submit written comments regarding this guidance at any time. Submit written comments on the guidance to the Division of Dockets Management (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. All comments should be identified with the title of the guidance document. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition January 1993; Revised July 2010 Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Background III. Discussion A. Petitions for Enzyme Preparations B. GRAS Notices for Enzyme Preparations IV. Recommendations for Petition or GRAS Notice Preparation A. Identity B. Manufacturing Process C. Specifications for Identity and Purity D. Intended Technical Effects and Use E. Intake Estimate V. Additional Information A. Enzyme Preparations Used in Meat and Poultry Processing B. Enzyme Preparations Containing Allergenic Ingredients 2 Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Guidance for Industry1 Enzyme Preparations: Recommendations for Submission of Chemical and Technological Data for Food Additive Petitions and GRAS Notices This guidance represents the Food and Drug Administration’s current thinking on this topic. It does not create or confer any rights for or on any person and does not operate to bind FDA or the public. -

AMP-Activated Protein Kinase: the Current Landscape for Drug Development

REVIEWS AMP-activated protein kinase: the current landscape for drug development Gregory R. Steinberg 1* and David Carling2 Abstract | Since the discovery of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) as a central regulator of energy homeostasis, many exciting insights into its structure, regulation and physiological roles have been revealed. While exercise, caloric restriction, metformin and many natural products increase AMPK activity and exert a multitude of health benefits, developing direct activators of AMPK to elicit beneficial effects has been challenging. However, in recent years, direct AMPK activators have been identified and tested in preclinical models, and a small number have entered clinical trials. Despite these advances, which disease(s) represent the best indications for therapeutic AMPK activation and the long-term safety of such approaches remain to be established. Cardiovascular disease Dramatic improvements in health care coupled with identifying a unifying mechanism that could link these (CVD). A term encompassing an increased standard of living, including better nutri- changes to multiple branches of metabolism followed diseases affecting the heart tion and education, have led to a remarkable increase in the discovery that the AMP-activated protein kinase or circulatory system. human lifespan1. Importantly, the number of years spent (AMPK) provided a common regulatory mechanism in good health is also increasing2. Despite these positive for inhibiting both cholesterol (through phosphoryla- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease developments, there are substantial risks that challenge tion of HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR)) and fatty acid (NAFLD). A very common continued improvements in human health. Perhaps the (through phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase disease in humans in which greatest threat to future health is a chronic energy imbal- (ACC)) synthesis8 (BOx 1). -

Characterisation, Classification and Conformational Variability Of

Characterisation, Classification and Conformational Variability of Organic Enzyme Cofactors Julia D. Fischer European Bioinformatics Institute Clare Hall College University of Cambridge A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 11 April 2011 This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. This dissertation does not exceed the word limit of 60,000 words. Acknowledgements I would like to thank all the members of the Thornton research group for their constant interest in my work, their continuous willingness to answer my academic questions, and for their company during my time at the EBI. This includes Saumya Kumar, Sergio Martinez Cuesta, Matthias Ziehm, Dr. Daniela Wieser, Dr. Xun Li, Dr. Irene Pa- patheodorou, Dr. Pedro Ballester, Dr. Abdullah Kahraman, Dr. Rafael Najmanovich, Dr. Tjaart de Beer, Dr. Syed Asad Rahman, Dr. Nicholas Furnham, Dr. Roman Laskowski and Dr. Gemma Holli- day. Special thanks to Asad for allowing me to use early development versions of his SMSD software and for help and advice with the KEGG API installation, to Roman for knowing where to find all kinds of data, to Dani for help with R scripts, to Nick for letting me use his E.C. tree program, to Tjaart for python advice and especially to Gemma for her constant advice and feedback on my work in all aspects, in particular the chemistry side. Most importantly, I would like to thank Prof. Janet Thornton for giving me the chance to work on this project, for all the time she spent in meetings with me and reading my work, for sharing her seemingly limitless knowledge and enthusiasm about the fascinating world of enzymes, and for being such an experienced and motivational advisor. -

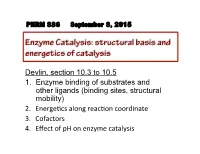

Enzyme Catalysis: Structural Basis and Energetics of Catalysis

PHRM 836 September 8, 2015 Enzyme Catalysis: structural basis and energetics of catalysis Devlin, section 10.3 to 10.5 1. Enzyme binding of substrates and other ligands (binding sites, structural mobility) 2. Energe(cs along reac(on coordinate 3. Cofactors 4. Effect of pH on enzyme catalysis Enzyme catalysis: Review Devlin sections 10.6 and 10.7 • Defini(ons of catalysis, transi(on state, ac(vaon energy • Michaelis-Menten equaon – Kine(c parameters in enzyme kine(cs (kcat, kcat/KM, Vmax, etc) – Lineweaver-Burk plot • Transi(on-state stabilizaon • Meaning of proximity, orientaon, strain, and electrostac stabilizaon in enzyme catalysis • General acid/base catalysis • Covalent catalysis 2015, September 8 PHRM 836 - Devlin Ch 10 2 Structure determines enzymatic catalysis as illustrated by this mechanism for ____ 2015, September 8 PHRM 836 - Devlin Ch 10 www.studyblue.com 3 Substrate binding by enzymes • Highly complementary interac(ons between substrate and enzyme – Hydrophobic to hydrophobic – Hydrogen bonding – Favorable Coulombic interac(ons • Substrate binding typically involves some degree of conformaonal change in the enzyme – Enzymes need to be flexible for substrate binding and catalysis. – Provides op(mal recogni(on of substrates – Brings cataly(cally important residues to the right posi(on. 2015, September 8 PHRM 836 - Devlin Ch 10 4 Substrate binding by enzymes • Highly complementary interac(ons between substrate and enzyme – Hydrophobic to hydrophobic – Hydrogen bonding – Favorable Coulombic interac(ons • Substrate binding typically involves some degree of conformaonal change in the enzyme – Enzymes need to be flexible for substrate binding and catalysis. – Provides op(mal recogni(on of substrates – Brings cataly(cally important residues to the right posi(on. -

The Crotonase Superfamily: Divergently Related Enzymes That Catalyze Different Reactions Involving Acyl Coenzyme a Thioesters

Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 145-157 similar three-dimensional architectures. In each protein, The Crotonase Superfamily: a common structural strategy is employed to lower the Divergently Related Enzymes free energies of chemically similar intermediates. Catalysis of the divergent chemistries is accomplished by both That Catalyze Different retaining those functional groups that catalyze the com- mon partial reaction and incorporating new groups that Reactions Involving Acyl direct the intermediate to new products. Indeed, as a Coenzyme A Thioesters specific example, the enolase superfamily has served as a paradigm for the study of catalytically diverse superfami- HAZEL M. HOLDEN,*,³ lies.3 The active sites of proteins in the enolase superfamily MATTHEW M. BENNING,³ are located at the interfaces between two structural TOOMAS HALLER,² AND JOHN A. GERLT*,² motifs: the catalytic groups are positioned in conserved Departments of Biochemistry, University of Illinois, regions at the ends of the â-strands forming (R/â) 8-barrels, Urbana, Illinois 61801, and University of Wisconsin, while the specificity determinants are found in flexible Madison, Wisconsin 53706 loops in the capping domains formed by the N- and Received August 9, 2000 C-terminal portions of the polypeptide chains. While the members of the enolase superfamily share similar three- ABSTRACT dimensional architectures, they catalyze different overall Synergistic investigations of the reactions catalyzed by several reactions that share a common partial reaction: abstrac- members of an enzyme superfamily provide a more complete tion of an R-proton from a carboxylate anion substrate understanding of the relationships between structure and function than is possible from focused studies of a single enzyme alone.