Public-Private Sector Relationships in a New Security Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vector Boolean Functions: Applications in Symmetric Cryptography

Vector Boolean Functions: Applications in Symmetric Cryptography José Antonio Álvarez Cubero Departamento de Matemática Aplicada a las Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones Universidad Politécnica de Madrid This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor Ingeniero de Telecomunicación Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros de Telecomunicación November 2015 I would like to thank my wife, Isabel, for her love, kindness and support she has shown during the past years it has taken me to finalize this thesis. Furthermore I would also liketo thank my parents for their endless love and support. Last but not least, I would like to thank my loved ones such as my daughter and sisters who have supported me throughout entire process, both by keeping me harmonious and helping me putting pieces together. I will be grateful forever for your love. Declaration The following papers have been published or accepted for publication, and contain material based on the content of this thesis. 1. [7] Álvarez-Cubero, J. A. and Zufiria, P. J. (expected 2016). Algorithm xxx: VBF: A library of C++ classes for vector Boolean functions in cryptography. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. (In Press: http://toms.acm.org/Upcoming.html) 2. [6] Álvarez-Cubero, J. A. and Zufiria, P. J. (2012). Cryptographic Criteria on Vector Boolean Functions, chapter 3, pages 51–70. Cryptography and Security in Computing, Jaydip Sen (Ed.), http://www.intechopen.com/books/cryptography-and-security-in-computing/ cryptographic-criteria-on-vector-boolean-functions. (Published) 3. [5] Álvarez-Cubero, J. A. and Zufiria, P. J. (2010). A C++ class for analysing vector Boolean functions from a cryptographic perspective. -

A Preliminary Empirical Study to Compare MPI and Openmp ISI-TR-676

A preliminary empirical study to compare MPI and OpenMP ISI-TR-676 Lorin Hochstein, Victor R. Basili December 2011 Abstract Context: The rise of multicore is bringing shared-memory parallelism to the masses. The community is struggling to identify which parallel models are most productive. Objective: Measure the effect of MPI and OpenMP models on programmer productivity. Design: One group of programmers solved the sharks and fishes problem using MPI and a second group solved the same problem using OpenMP, then each programmer switched models and solved the same problem again. The participants were graduate students in an HPC course. Measures: Development effort (hours), program correctness (grades), pro- gram performance (speedup versus serial implementation). Results: Mean OpenMP development time was 9.6 hours less than MPI (95% CI, 0.37 − 19 hours), a 43% reduction. No statistically significant difference was observed in assignment grades. MPI performance was better than OpenMP performance for 4 out of the 5 students that submitted correct implementations for both models. Conclusions: OpenMP solutions for this problem required less effort than MPI, but insufficient power to measure the effect on correctness. The perfor- mance data was insufficient to draw strong conclusions but suggests that unop- timized MPI programs perform better than unoptimized OpenMP programs, even with a similar parallelization strategy. Further studies are necessary to examine different programming problems, models, and levels of programmer experience. Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION In the high-performance computing community, the dominant parallel pro- gramming model today is MPI, with OpenMP as a distant but clear second place [1,2]. MPI’s advantage over OpenMP on distributed memory systems is well-known, and consequently MPI usage dominates in large-scale HPC sys- tems. -

Christmas Stars Many Use the Coco-Cola Advert As Their Favourite First Sign of Christmas but at St

December 2018 Christmas Stars Many use the Coco-Cola advert as their favourite first sign of Christmas but at St. Ed’s it is always our Nativity performances that signal Christmas is on its way! This year, our traditional nativity was performed by our Form 1 and Form 2 children who entertained their proud audience with an array of new festive songs including ‘A Great Big Star’ and “It’s a squash, it’s a squeeze”. #St. Ed’s defies anybody who left the Chapel that day without a tear in their eye! The following day it was our Early Years children who turned the Chapel into a winter wonderland of animals helping Rudolph who had lost his nose! After all of the animals kindly offered Rudolph alternatives, including a carrot and a star, it was Mr Walliker himself who saved the day as Rudolph’s nose appeared in his pocket! Thank Christmas for Mr Walliker! Congratulations to our Ties! Welcome Many congratulations to Ella Chauhan, Madelaine Murrin, Jake Paterson, Guy van Baby Michael Oudtshoorn and Erin Wilson who were awarded their Prefect “ties” this term. Voted for by the school staff, the “ties” role is to support the Heads of Prep Mr Church School, Kitty and Freddie, and assume particular responsibilities in and around the and his wife school. Quoting Churchill, “the price of greatness is responsibility” so well done Jitka are to you all for your more than deserving recognition. delighted to announce the birth of their son, Michael who arrived in this world on Saturday 17th November at 8.00 am weighing in at 8 lbs. -

Identifying Open Research Problems in Cryptography by Surveying Cryptographic Functions and Operations 1

International Journal of Grid and Distributed Computing Vol. 10, No. 11 (2017), pp.79-98 http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijgdc.2017.10.11.08 Identifying Open Research Problems in Cryptography by Surveying Cryptographic Functions and Operations 1 Rahul Saha1, G. Geetha2, Gulshan Kumar3 and Hye-Jim Kim4 1,3School of Computer Science and Engineering, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India 2Division of Research and Development, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India 4Business Administration Research Institute, Sungshin W. University, 2 Bomun-ro 34da gil, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea Abstract Cryptography has always been a core component of security domain. Different security services such as confidentiality, integrity, availability, authentication, non-repudiation and access control, are provided by a number of cryptographic algorithms including block ciphers, stream ciphers and hash functions. Though the algorithms are public and cryptographic strength depends on the usage of the keys, the ciphertext analysis using different functions and operations used in the algorithms can lead to the path of revealing a key completely or partially. It is hard to find any survey till date which identifies different operations and functions used in cryptography. In this paper, we have categorized our survey of cryptographic functions and operations in the algorithms in three categories: block ciphers, stream ciphers and cryptanalysis attacks which are executable in different parts of the algorithms. This survey will help the budding researchers in the society of crypto for identifying different operations and functions in cryptographic algorithms. Keywords: cryptography; block; stream; cipher; plaintext; ciphertext; functions; research problems 1. Introduction Cryptography [1] in the previous time was analogous to encryption where the main task was to convert the readable message to an unreadable format. -

A Brief Outlook at Block Ciphers

A Brief Outlook at Block Ciphers Pascal Junod Ecole¶ Polytechnique F¶ed¶eralede Lausanne, Suisse CSA'03, Rabat, Maroc, 10-09-2003 Content F Generic Concepts F DES / AES F Cryptanalysis of Block Ciphers F Provable Security CSA'03, 10 septembre 2003, Rabat, Maroc { i { Block Cipher P e d P C K K CSA'03, 10 septembre 2003, Rabat, Maroc { ii { Block Cipher (2) F Deterministic, invertible function: e : {0, 1}n × K → {0, 1}n d : {0, 1}n × K → {0, 1}n F The function is parametered by a key K. F Mapping an n-bit plaintext P to an n-bit ciphertext C: C = eK(P ) F The function must be a bijection for a ¯xed key. CSA'03, 10 septembre 2003, Rabat, Maroc { iii { Product Ciphers and Iterated Block Ciphers F A product cipher combines two or more transformations in a manner intending that the resulting cipher is (hopefully) more secure than the individual components. F An iterated block cipher is a block cipher involving the sequential repeti- tion of an internal function f called a round function. Parameters include the number of rounds r, the block bit size n and the bit size k of the input key K from which r subkeys ki (called round keys) are derived. For invertibility purposes, the round function f is a bijection on the round input for each value ki. CSA'03, 10 septembre 2003, Rabat, Maroc { iv { Product Ciphers and Iterated Block Ciphers (2) P K f k1 f k2 f kr C CSA'03, 10 septembre 2003, Rabat, Maroc { v { Good and Bad Block Ciphers F Flexibility F Throughput F Estimated Security Level CSA'03, 10 septembre 2003, Rabat, Maroc { vi { Data Encryption Standard (DES) F American standard from (1976 - 1998). -

The Block Cipher SC2000

The Block Cipher SC2000 Takeshi Shimoyama1, Hitoshi Yanami1, Kazuhiro Yokoyama1, Masahiko Takenaka2, Kouichi Itoh2, Jun Yajima2, Naoya Torii2, and Hidema Tanaka3 1 Fujitsu Laboratories LTD. 4-1-1, Kamikodanaka Nakahara-ku Kawasaki 211-8588, Japan {shimo,yanami,kayoko}@flab.fujitsu.co.jp 2 Fujitsu Laboratories LTD. 64, Nishiwaki, Ohkubo-cho, Akashi 674-8555, Japan {takenaka,kito,jyajima,torii}@flab.fujitsu.co.jp 3 Science University of Tokyo Yamazaki, Noda, Chiba, 278 Japan [email protected] Abstract. In this paper, we propose a new symmetric key block cipher SC2000 with 128-bit block length and 128-,192-,256-bit key lengths. The block cipher is constructed by piling two layers: one is a Feistel structure layer and the other is an SPN structure layer. Each operation used in two layers is S-box or logical operation, which has been well studied about security. It is a strong feature of the cipher that the fast software implementations are available by using the techniques of putting together S-boxes in various ways and of the Bitslice implementation. 1 Introduction In this paper, we propose a new block cipher SC2000. The algorithm has 128-bit data inputs and outputs and 128-bit, 192-bit, and 256-bit keys can be used. Our design policy for the cipher is to enable high-speed in software and hardware processing on various platforms while maintaining the high-level security as ci- pher. The cipher is constructed by piling a Feistel and an SPN structures with S-boxes for realizing those properties. For evaluation of security, we inspect the security in the design against dif- ferential attacks, linear attacks, higher order differential attacks, interpolation attacks, and so on. -

Basic Cryptanalysis Methods on Block Ciphers

1 BASIC CRYPTANALYSIS METHODS ON BLOCK CIPHERS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF APPLIED MATHEMATICS OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY DILEK˙ C¸ELIK˙ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CRYPTOGRAPHY MAY 2010 Approval of the thesis: BASIC CRYPTANALYSIS METHODS ON BLOCK CIPHERS submitted by DILEK˙ C¸ELIK˙ in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Department of Cryptography, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Ersan AKYILDIZ Director, Graduate School of Applied Mathematics Prof. Dr. Ferruh OZBUDAK¨ Head of Department, Cryptography Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali DOGANAKSOY˘ Supervisor, Department of Mathematics, METU Examining Committee Members: Prof. Dr. Ferruh OZBUDAK¨ Department of Mathematics, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali DOGANAKSOY˘ Department of Mathematics, METU Assist. Prof. Dr. Zulf¨ ukar¨ SAYGI Department of Mathematics, TOBB ETU Dr. Muhiddin UGUZ˘ Department of Mathematics, METU Dr. Murat CENK Department of Cryptography, METU Date: I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: DILEK˙ C¸ELIK˙ Signature : iii ABSTRACT BASIC CRYPTANALYSIS METHODS ON BLOCK CIPHERS C¸elik, Dilek M.S., Department of Cryptography Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali DOGANAKSOY˘ May 2010, 119 pages Differential cryptanalysis and linear cryptanalysis are the first significant methods used to at- tack on block ciphers. These concepts compose the keystones for most of the attacks in recent years. -

Image Munitions and the Continuation of War and Politics by Other Means

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Image warfare in the war on terror: Image munitions and the continuation of war and politics by other means. Roger, Nathan Philip How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Roger, Nathan Philip (2010) Image warfare in the war on terror: Image munitions and the continuation of war and politics by other means.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42350 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Image warfare in the war on terror: Image munitions and the continuation of war and politics by other means Nathan Philip Roger Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Swansea University 2010 ProQuest Number: 10798058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Applying Conditional Linear Cryptanalysis to Ciphers with Key- Dependant Operations

Applying Conditional Linear Cryptanalysis to Ciphers with Key- Dependant Operations REINER DOJEN TOM COFFEY Data Communications Security Laboratory Department of Electronic and Computer Engineering University of Limerick IRELAND Abstract: - Linear cryptanalysis has been proven to be a powerful attack that can be applied to a number of symmetric block ciphers. However, conventional linear cryptanalysis is ineffective in attacking ciphers that use key-dependent operations, such as ICE, Lucifer and SAFER. In this paper conditional linear cryptanalysis, which uses characteristics that depend on some key-bit values, is introduced. This technique and its application to symmetric ciphers are analysed. The consequences of using key-dependent characteristics are explained and a formal notation of conditional linear cryptanalysis is presented. As a case study, conditional linear cryptanalysis is applied to the ICE cipher, which uses key-dependant operations to improve resistance against cryptanalysis. A successful attack on ThinICE using the new technique is presented. Further, experimental work supporting the effectiveness of conditional linear cryptanalysis is also detailed., Key-Words: - Cryptography, Cryptanalysis, Linear cryptanalysis, Symmetric ciphers, Attack 1 Introduction In contrast to differential cryptanalysis, linear As the volume of data transmitted over the world's cryptanalysis uses linear approximations to describe expanding communication networks increases so the F-function of a block cipher. Thus, if some also does the demand for data security services such plaintext bits and ciphertext bits are XORed as confidentiality and integrity. This protection can together, then the result equals the XOR of some be achieved by using either a public key cipher or a bits of the key (with a probability p, for the key) and symmetric cipher. -

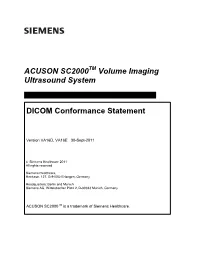

ACUSON SC2000TM Volume Imaging Ultrasound System

ACUSON SC2000TM Volume Imaging Ultrasound System XXXXXXXXXXXXxxXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX DICOM Conformance Statement Version VA16D, VA16E 30-Sept-2011 © Siemens Healthcare 2011 All rights reserved Siemens Healthcare, Henkestr. 127, D-91052 Erlangen, Germany Headquarters: Berlin and Munich Siemens AG, Wittelsbacher Platz 2, D-80333 Munich, Germany ACUSON SC2000TM is a trademark of Siemens Healthcare. TM ACUSON SC2000 Volume Imaging Ultrasound System DICOM Conformance Statement CONFORMANCE STATEMENT OVERVIEW The ACUSON SC2000TM Volume Imaging Ultrasound System supports the following DICOM Application Entities: - Verification o Verification AE - Transfer o Storage AE o Storage Commitment AE - Query / Retrieve o Query AE o Retrieve AE - Workflow Management o Worklist AE o MPPS AE Table 1. NETWORK SERVICES Service Class User Service Class Provider SOP Classes (SCU) (SCP) VERIFICATION Verification AE Verification Yes Yes TRANSFER Storage AE Ultrasound Image Storage Yes Yes Ultrasound Multi-frame Image Storage Yes Yes Secondary Capture Image Storage Yes Yes Comprehensive SR Yes Yes Raw Data Storage Yes Yes Storage Commitment AE Storage Commitment Push Model Yes No QUERY / RETRIEVE Query AE Study Root Query/Retrieve Information Model – FIND Yes No Retrieve AE Study Root Query/Retrieve Information Model – MOVE Yes No WORKFLOW MANAGEMENT Worklist AE Modality Worklist Yes No MPPS AE MPPS (N-Create, N-Set) Yes No © Siemens Healthcare, 2011 Version VA16D/E Page 2 of 111 TM ACUSON SC2000 Volume Imaging Ultrasound System DICOM Conformance Statement Table -

Research Problems in Block Cipher Cryptanalysis: an Experimental Analysis Amandeep, G

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8 Issue-8S3, June 2019 Research Problems in Block Cipher Cryptanalysis: An Experimental Analysis Amandeep, G. Geetha Abstract: Cryptography has always been a very concerning Organization of this paper is as follows. Section 2 lists the issue in research related to digital security. The dynamic need of Block ciphers in a chronological order in a table having six applications and keeping online transactions secure have been columns stating name of the algorithm, year of publication, giving pathways to the need of developing different its cryptographic strategies. Though a number of cryptographic structure, block size, key size, and the cryptanalysis done on algorithms have been introduced till now, but each of these algorithms has its own disadvantages or weaknesses which are that particular cipher. This table becomes the basis of the identified by the process of cryptanalysis. This paper presents a analysis done in Section 3 and tabulates the information as to survey of different block ciphers and the results of attempts to which structure has been cryptanalyzed more, thereby identify their weakness. Depending upon the literature review, establishing a trend of structures analyzed Section 4 some open research problems are being presented which the identifies the open research problems based on the analysis cryptologists can depend on to work for bettering cyber security. done in Section 3. Section 5 of the paper, presents the conclusion of this study. Index Terms: block ciphers, cryptanalysis, attacks, SPN, Feistel. II. RELATED WORK I. INTRODUCTION This paper surveys 69 block ciphers and presents, in Cryptography is the science which deals with Table I, a summarized report as per the attacks concerned. -

Secure Implementation of Block Ciphers Against Physical Attacks Dahmun Goudarzi

Secure Implementation of Block Ciphers against Physical Attacks Dahmun Goudarzi To cite this version: Dahmun Goudarzi. Secure Implementation of Block Ciphers against Physical Attacks. Cryptography and Security [cs.CR]. ENS Paris - Ecole Normale Supérieure de Paris, 2018. English. tel-01896103v2 HAL Id: tel-01896103 https://hal.inria.fr/tel-01896103v2 Submitted on 24 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE DE DOCTORAT de l’Université de recherche Paris Sciences et Lettres PSL Research University Préparée à l’École normale supérieure Secure Implementation of Block Ciphers against Physical Attacks École doctorale n◦386 Sciences Mathématiques de Paris Centre Spécialité Informatique COMPOSITION DU JURY Mme. Canteaut Anne INRIA Paris Examinatrice M. Fouque Pierre-Alain Université de Rennes 1 Rapporteur Mme. Handschuh Helena Rambus Soutenue par Examinatrice Dahmun Goudarzi M. Pointcheval David le 21 septembre 2018 CNRS, École normale supérieure Examinateur M. Renault Guénaël Dirigée par ANSSI Matthieu Rivain et Examinateur Damien Vergnaud M. Rivain Matthieu CryptoExperts Directeur de thèse M. Schwabe Peter RESEARCH UNIVERSITY PARIS Radboud University ÉCOLE NORMALE SUPÉRIEURE Rapporteur M. Vergnaud Damien UPMC Directeur de thèse Secure Implementation of Block Ciphers against Physical Attacks Dahmun Goudarzi Thèse de doctorat dirigée par Matthieu Rivain et Damien Vergnaud Résumé Depuis leur introduction à la fin des années 1990, les attaques par canaux auxiliaires sont considérées comme une menace majeure contre les implémentations cryptographiques.